When The New Yorker published its first “Science Fiction Issue” last summer, most of the guests were either genre eminences whose acclaim slowly caught up with their influence—William Gibson, Ursula K. LeGuin—or mainstream novelists known for dipping in and out of overt unreality, like Junot Diaz, Colson Whitehead, and Jennifer Egan.

Of the contributors under 60, only China Miéville, author most recently of Embassytown and Railsea, scrabbled up from the bookshop backwaters. He hasn’t come to be seen as an exemplar of the young and weird in fiction by eschewing geekiness. One of his books climaxes with golems and elementals battling each other in D&D monster manual numbers: wild predatory pyro-creatures, a construct of mirrored light, the lunar avatar skeletally inhabiting its “fold of space.” Miéville delights in anachronisms and neologisms alike. What he rejects is the idea that a writer must be reactionary about all this, be made insular by past critical derision, defensively tending to inherited clichés.

The fraught political systems and sexualities of Miéville’s novels are believably manifold, but he doesn’t skimp on bizarre beings, either, from spiny cactus-people and the Lovecraftian “grindylow” to a crime boss in the form of a sentient tattoo. Avoiding crude allegory, he imagines the cultural implications of each fantastical species and scatters some intriguingly partial details. What would the cacti-ghetto be in a city dominated by homo sapiens? (An enormous greenhouse, of course.) How might a human/mostly-humanoid-but-beetle-above-the-neck couple negotiate that society? Some Miéville creatures have a consciousness so utterly alien, motivations so remote, that their otherness reveals the artifice gluing together our own human narratives, social codes and protocols—which he then plays with gleefully.

Apart from the novelist’s resemblance to an Oi band frontman, his materialist, demystifying bent could explain why Miéville and like-minded writers feel unthreatened by “literary” fiction: in a genre jambalaya, it’s just another flavour. A world in a galaxy in a universe.

An Incomplete Biographical Taxonomy of Miéville’s Worlds

London, 1970s

China Miéville is born to “hippie parents” in 1972 and arrives in the city shortly afterwards. Thirty years later, he told an interviewer that “the story is that they went through a dictionary looking for a beautiful word to name me. They nearly called me Banyan, but flipped a few pages on and reached ‘China,’ thankfully.” The author only met his father a handful of times. His mother eventually moved the family to Willesden, a working-class, ethnically diverse district of northwestern London, and after stints in Cambridge, Cairo and Zimbabwe, he lives nearby still. Debut novel King Rat, a drum-and-bass-scored revision of the Pied Piper legend, begins in Willesden.

Miéville’s aforementioned New Yorker piece, an “email sent back in time to a young science-fiction fan,” recalls: “In that class full of six-year-olds, everyone was into dinosaurs and/or magic and/or Saturday-morning monsters, just like you…Mostly those ‘into this’ are those who simply never leave.” And though Beatrix Potter, H. P. Lovecraft and Orlando were all key discoveries, “the hankering for anything that gets you in the sweet spot of the strange can act as a conduit into other traditions,” leading him to Jane Eyre and Leonora Carrington in turn.

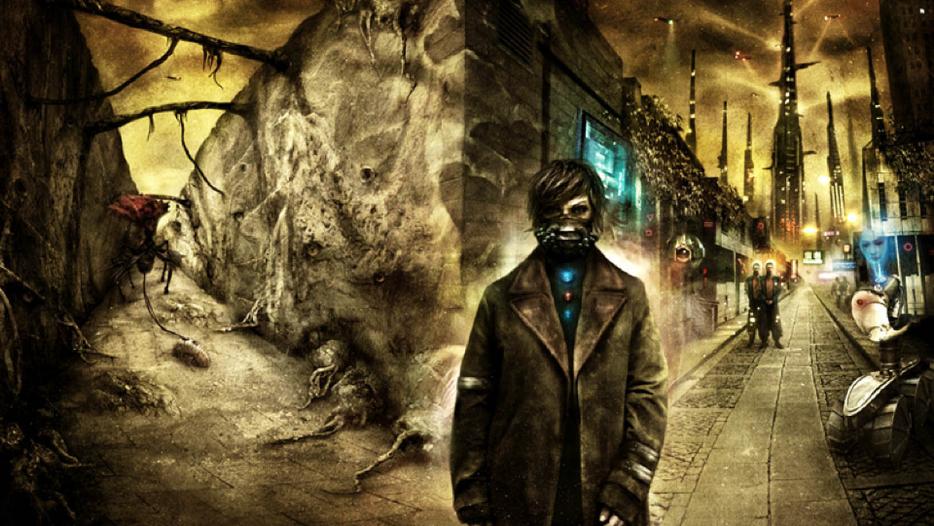

Bas-Lag

A world of arcane magic (or “thaumaturgy”) and steampunk technology, explored by Miéville in three successive novels, Perdido Street Station, The Scar and Iron Council. Their primary setting is New Crobuzon, an authoritarian oligarchy in parliamentary guise, where votes are awarded via corrupt lottery and police-state dirigibles loll across the skyline. Despite its grand imperial schemes, the metropolis is periodically roiled by radical uprisings, rival powers’ intrigues and, at one point, an infestation of monstrous, dream-eating moths. In the Bas-Lag novels, such events often force desperate, agonized political/moral/teleological dilemmas onto characters with baroque names (Isaac Dan der Grimnebulin, Uther Doul, Bellis Coldwine).

New Crobuzon is the centre of gravity in the Bas-Lag books, a capital of capital, but Miéville does venture elsewhere. The Scar primarily takes place on Armada, a roaming piratical city composed of lashed-together ships, while Iron Council describes the titular renegade train’s flight through a quasi-Western wilderness. There are intimations of places stranger still: High Cromlech, where aristocratic liches rule a zombie proletariat and starved, blood-begging vampires; the casino-parliament of Maru-ahm, “where laws were stakes in games of roulette;” Troglodopolis, a winding “chthonic burrow.”

London, 1850s

New Crobuzon is evocative of Victorian London in several ways, even before considering its creator’s Marxism—though Miéville argues that this only indirectly influences his fiction. He does have other outlets, after all: his PhD thesis from the London School of Economics was published as Between Equal Rights: A Marxist Theory of International Law. Miéville also ran as a Socialist Alliance candidate in the UK’s 2001 general election, receiving 1.2% of the vote and leaving the British Parliament sadly bereft of any MPs with huge tentacled-skull tattoos on their arm.

Besźel/Ul Qoma

The City & the City might arguably circle around the fantastic entirely; its premise is elaborately, madly tenable. Somewhere in eastern Europe, two urbanities share one space, enmeshing and intersecting with each other. Certain parts of the built environment lie wholly in Besźel, others in Ul Qoma, and some are “crosshatched,” doubly public spaces. Aside from subtle cues of fashion or architecture, nothing demarcates the bound twins. Anyone who passes between cities or even acknowledges the second one’s existence without using a lone official “border” risks harsh punishment from the secretive organization known as Breach. Following the police detective Tyador Borlu, whose investigations of a foreign student’s murder become increasingly labyrinthine, it’s an odd crime novel, almost allegory, with Miéville’s sparest prose yet: a cartographic hallucination of the divided city.

Arieka

A distant colony of an interstellar human empire—or rather a small fraction of the planet, colonized and dubbed Embassytown (from the book of the same name). The indigenous Ariekei “Hosts” tolerate this arrangement, one trusts, because their dialect encompasses nothing but literalisms. They can’t lie—or use metaphors, which are a kind of lie. To speak figuratively, they must first make the phrase a physical reality. In her youth, Miéville’s protagonist Avice Benner Cho undergoes a mysteriously unpleasant ritual and becomes a simile: “I’m like the girl who was hurt in darkness and ate what was given her.” It’s supposed to be wryly stoic.

Avice’s linguist husband Scile observes: “They don’t have polysemy. Words don’t signify: they are their referents. How can they be sentient and not have symbolic language? How do their numbers work? It makes no sense.” But that impossible illogic hangs together plausibly enough on the page, substituting extraordinary semiotics for the fanciful hyperdrives of traditional science fiction. Embassytowners bred to mimic Hosts’ double-voiced talk are known as Ambassadors, the colony’s doppelganger gentry; when imperial politics deliver a new type of envoy to Arieka, the natives get hopelessly, dangerously addicted to their very speech, hooked on the “god-drug” of the Word. Having pulled off the far-future equivalent of moving to New York and abandoned her sheltered homeworld for cosmic escapades, Avice finds herself scrambling to prevent vicious societal collapse. Miéville makes it clear that any remedy will not, cannot come through restoration. Another bizarre yet bracing notion: the revolution that’s only comprehensible after it already happened.

China Miéville will be making two appearances at this year’s International Festival of Authors at Harbourfront Centre in Toronto. On October 25th, he is giving The Walrus magazine’s Keynote Address alongside Miriam Toews. The following day he appears as part of an IFOA reading/interview with Cory Doctorow.