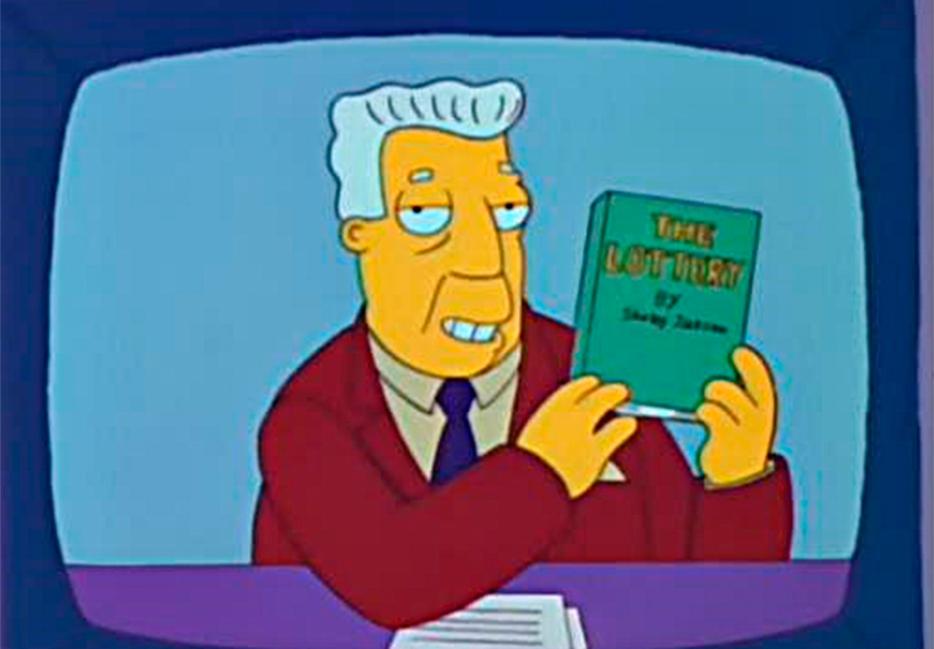

“Every copy of Shirley Jackson's The Lottery has been checked out from the Springfield public library,” says news anchor Kent Brockman on an episode from the third season of The Simpsons. The prize is up to 130 million dollars, and people are obsessed with the prospect of winning. “Of course the book does not contain any hints on how to win the lottery. It is rather a chilling tale of conformity gone mad.” Cut to a frustrated Homer Simpson watching TV from his couch, chucking his copy of The Lottery into the fireplace.

I learned about Shirley Jackson through The Simpsons a decade before I was assigned an essay analyzing the symbolism in The Lottery in a high school English class. Discovering her through a satirical animated sitcom feels retroactively all too perfect; she was a smart writer with genre appeal. Time magazine once described her as “A Virginia Werewoolf amongst the scéance-fiction writers,” a moniker that her husband, a literary critic, would resent for its dismissiveness. She could be deeply funny, and not in the “dark irony that comes with living in modern society expressed through an acerbic wit” way but in a “here are my jokes, look at my jokes, I am clever in ways you can only dream of being” kinda way. Her abilities to terrify and delight and then terrify some more lend an evergreen quality to her books, most of which were written in the 1950s.

Shirley Jackson would be turning one hundred years old this December had she not passed away in 1965, at the age of forty-eight. In time for her centennial comes A Rather Haunted Life, an excellent new biography out this month by Ruth Franklin. (Judy Oppenheimer’s 1988 book, Private Demons: The Life of Shirley Jackson, is frustratingly out of print.) The list of Jackson’s own work currently still in print includes six novels, three short story and essay collections, and two memoirs. No detail in a Shirley Jackson story is put there by accident, as evidenced in the lectures on writing she gave, collected in the posthumous collections Let Me Tell You and Come Along With Me. I myself tore through her works voraciously, as if all the secrets of surviving this world were hidden somewhere on the last page. She would write about how things were, but not how we got there; a town with an annual ritual sacrifice of one of its own was a given, with readers left to fill in the blanks with their own experiences of, well, conformity gone mad.

Women frequently get the shaft in Shirley Jackson’s stories. It’s not that her men are never victims, but the women are the ones who truly seem to suffer. They’re also the prime antagonists—the ones who judge their neighbours, control their daughters, whisper and gossip about anyone who crosses their paths. They’re the ones who know, way better than the menfolk ever will, what it takes to sacrifice yourself to be a person in the world, and they’ll be damned if anyone else gets away scot free. They hurt, and so they cause hurting in turn.

Jackson herself suffered in life, from her overbearing mother, from her unfaithful husband, from trying to carve out time away from raising four children for her creative work, writing stories for publications that frequently asked her for more light-hearted tales. She omits the darker parts of her life in her two memoirs, Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons, lighthearted comedies based on her children’s misadventures. The darker truths she saved for her fiction. Shirley Jackson wrote what she knew, but also what she believed, what she feared, and what she was constantly trying to run away from.

She experienced severe agoraphobia later in life, rarely leaving her home. She was obsessed with houses. They were her ultimate muses. She liked ‘em big and spooky, and she liked the narratives behind them. They’re a frequent motif in her books, integral to the plots of We Have Always Lived in the Castle and The Sundial, and serving as a character in The Haunting of Hill House. Both her jovial and her horror stories took place in domestic spaces. Jackson understood firsthand what it was like to lose parts of yourself in order to fit in with expectations from others, and her fiction was a way to explore that, taking stifling social obligations to their dramatic conclusions. Like Mrs. Hutchinson in The Lottery, Jackson often had little room to dissent against conformity in her day-to-day life. She did, however, have her writing.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle

“My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all, I could have been a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had. I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise. I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and Amanita phalloides, the death-cup mushroom. Everyone else in our family is dead.”

Starting with Jackson’s last completed novel is a bit like eating dessert before dinner but that’s okay; she would approve of that. This novella, told in poetic prose from the point of view of an eighteen-year-old trapped in her prepubescent mindset, is Jackson’s masterpiece.

Mary Katherine Blackwood—Merricat—lives alone with her sister and uncle in a big empty house, six years after the rest of their family was murdered via arsenic in the sugar bowl. The murder is technically unsolved, but the book’s not really a whodunit. Constance’s agoraphobia leaves her housebound. Merricat is a dreamer, imagining a celestial life for her and Constance in which they wear feathers in their hair and rubies on their hands, speaking a soft, liquid tongue and singing in the starlight, looking down on the dead dried world.

Every sentence is filled with this type of elegance, of terror told delicately and cobwebs spun into gold. Merricat’s narration is a nimble highwire act: naive but not innocent, observant but dreamlike, present but a million miles away, somewhere on the surface of the moon. On a regular day, Jackson could provide scares, but at her best she could quietly unsettle. Merricat is an outsider, ostracized from everyone except her sister, but it’s her inviting view of the world contrasted with the harshness of the townsfolk that slowly becomes the only thing that makes sense.

Long before she was invited to participate in a study of the supernatural at the notorious Hill House, Eleanor Vance was trapped. She is maddeningly lonely, having spent most of her adult life as the caretaker for her dying mother before living under the thumb of her domineering sister and brother-in-law. Eleanor is a bit of an introvert, the type made famous on your Tumblr dashboard, but more than that she doesn't know who she is—she hasn’t had the freedom yet to develop a personality. So when the opportunity comes up to steal her sister’s car and run away to an allegedly haunted house with a bunch of paranormally inclined strangers, Eleanor’s inclination is to go, “Cool, where can I stop for gas?” This is how she ends up at Hill House, a place where monsters and metaphors hang out all night on a never-ending slumber party. (The book was adapted into a movie in 1963, and again in 1999 as a Razzie nominated gore flick starring Owen Wilson. I haven’t seen it, but I can assure you it’s terrible.)

Hill House is disorienting and claustrophobic, and though all of its residents are thrown off by its winding hallways and disproportionate dimensions, Eleanor seems to be affected the most. She’s the one the voices in the night call out to, it’s her name that shows up on the walls in blood. The house seems to physically manifest all her anxieties, isolating her from everyone else and singling her out as a current for deviance. The Haunting of Hill House is, perchance, a straightforward horror novel, but only because it’s built on a foundation of paranoia and self doubt, where the line between real and imaginary is blurred. Whether the house is actually haunted or Eleanor is simply losing her mind, both options read as pretty terrifying.

If she was at all ambiguous about the unreliability of the narrator in Hill House (I mean, if you wanted to take a very literal reading), Jackson downright torpedoes the idea that anything can be trusted at face value in these two books. Her second and third novels, written in 1951 and 1954 respectively, follow female heroes who endure unacknowledged trauma and suffer the mental consequences.

Natalie, the teenage protagonist of Hangsaman, lives very much in her own head, mostly as a way to deal with her dysfunctional family. The day before she leaves for college, she is maybe sexually assaulted—an incident that is maybe based on Jackson’s real life. While at school, Natalie isolates herself from the girls at her dormitory, but forges a friendship with Elizabeth, the alcoholic wife of one of her teachers—two characters that are maybe based on Jackson and her own husband, who worked as a lecturer at a university. Then things get weird.

Elizabeth, the mousy twenty-three-year-old protagonist of The Bird’s Nest, lives a mostly quiet life spent working at the museum. There are things happening in her life she can’t explain: mysterious headaches and fatigue, gaps in memory and time she can’t piece together. Her uptight aunt forces her to see a psychiatrist, the perfunctory Dr. Wright. Through hypnosis, he makes a remarkable discovery: within Elizabeth are no fewer than three completely distinct personalities, each vying for their chance in the spotlight.

Whatever DSM-V classifications might be given to Natalie and Elizabeth today—PTSD, dissociative identity disorder—Jackson was working with the information they had at the time, falling back on her metaphors. It’s after being forced into a state of repression that both Natalie’s and Elizabeth’s subconscious come out to play with little regard for anything else. The science in these books is ambiguous, but the social conditions that require in women a state of submission are anything but.

The Lottery & Other Stories

“The Lottery,” which closes out this story collection, is by far Jackson’s most famous work—thanks, Kent Brockman. After it was published in The New Yorker in 1948, it received a record number of letters to the editor, ranging from the hostile to the befuddled to the even more hostile. People demanded explanations for the story, or mistook it for non-fiction.

“The Lottery” draws readers into a false sense of security within the first few paragraphs. It opens on a small town, where everybody knows each other’s name and gathers together for an annual tradition. Sure, there seems to be an unspoken chill in the air, but what small town doesn’t have one of those? Everything is perfectly fine and normal, until the lottery is drawn and the mob is formed and the readers of The New Yorker are forever changed.

The rest of the book includes stories that start off like romantic escapades but quickly devolve into parables about the Devil, tight social satire you may have to read twice in order to fully grasp the critique of anti-Semitism, and creepily uncanny depictions of Americana.

As far as Jackson’s female characters go, the women of The Sundial are especially brutal. The book opens on the Halloran Estate, after the funeral of Lionel Halloran. His wife, Maryjane, believes that his mother, Orianna, murdered Lionel to inherit the estate. His young daughter, Fancy, in turn offers to push Orianna down the stairs. There are other family members and live-in help present, none of them equipped to be in the same room together. This is page one of the book.

When wandering in the garden, Aunt Fanny (Orianna’s sister-in-law) has a vision: the end of the world is coming, and only those in the Halloran house will survive. The family quickly accepts their fate as the chosen few, and soon starts to prepare for life in a new world where they account for the entire population. Shirley’s comedy is pitch black here; if a funeral brought out the family’s ugly side, the apocalypse warps them into funhouse mirror versions of real people. The end of the world is just another social obligation.

Jackson’s first novel is an excellent deep cut. It follows the residents of Pepper Street in small-town California, and the social dynamics that keep everyone in line. It’s the Seinfeld of middle-class suburban ennui: a book about nothing and therefore about everything. Jackson once said that the first book you have to write is to get back at your parents, and The Road is her big two-hundred-page middle finger to her own suffocating California childhood. Once she got that out of her system, Jackson was ready to take on the rest of the world.