It is rare to read intimate stories about people struggling against the weight of modern dictatorships. Rarer still are the urgent depictions of people trapped by history, living in fear.

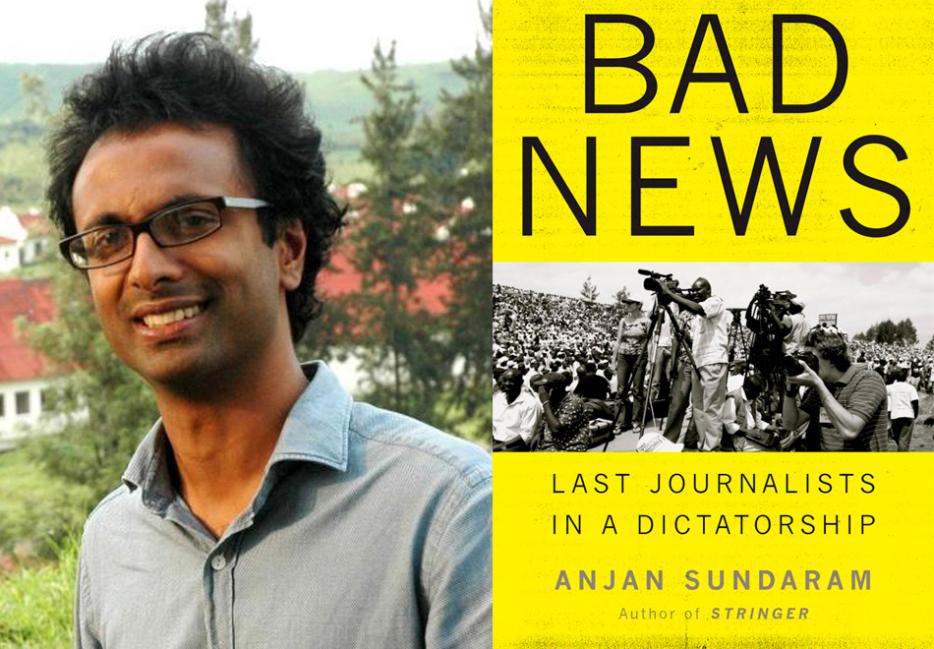

In Bad News: Last Journalists in a Dictatorship, writer Anjan Sundaram takes the reader into the heart of Rwanda, a country that is hard to know and is still battling demons of a genocide that occurred more than 20 years ago. During his near five-year stint in Kigali, Sundaram ran a journalism training program and discovered, through the experiences of his students, what it’s like to quietly defy the state.

“You cannot pay attention to what they show you,” one of his students says of the government, “but need to listen to those they keep silent.”

Sundaram’s astonishing account of Rwandan voices silenced could only have been possible through careful observation and immersion. His earlier work, an intense portrait of the Democratic Republic of Congo, used similar telescopic, story-telling techniques. Sundaram recently spoke to me about learning how to look at a dictatorship.

*

Judi Rever: In your first book, Stringer, there’s a cinematic moment where you meet up in Kinshasa with a teenager named Guy who makes a living on the streets. He’s with a friend named Patrick and a girl named Sylvia with eyes “large like leaves” who inhales a joint through her nose. You strike off to the stadium on a lark, at night, on a two-wheeler—recklessly enjoying the ride—and you’re holding hands with them as you walk up the stairs of the coliseum. You describe them expressing a range of emotions, from anger to joy. It’s an incredible few pages. It’s unusual because you’re not only an observer; there’s very little distance between you and them. It sets the tone for the book. Is it something that you set out to do, engaging with people so closely or did it just happen spontaneously because you were in Africa or in Congo?

Anjan Sundaram: I think the intention I set out with is to immerse myself in an environment and in a place and with people. And that certainly comes before I even think of conceiving anything, even a book. That’s how I like to explore the world and live in the world. That’s what happened both in Congo and Rwanda. In both cases I went without an explicit plan to write a book. I just began to live as fully as I could and try to reduce the distance, as you say, between me and the places I am in—to try and see the world from their point of view. I begin as a person looking in from the outside, and the reader goes on a journey with me as I unravel and explore and am exposed to both Congo and Rwanda. And along the way you meet characters who help me in that exploration and become companions for both me and the reader. This is very much how I like to tell a story.

You’ve been compared to a young V.S. Naipaul for your “discerning curiosity.” How do you see yourself when you read that kind of comparison? As a writer you’re a professional observer, but in these books what we’re getting is something more extraordinary. We’re getting your observations, but it’s almost as though we’re moving away from you and we’re experiencing your characters viscerally. So the attention shifts completely.

Through my closeness with my environment and with my characters, the reader begins to feel like they’re exposed to that environment and they’re feeling it through me. How do I feel? I feel like each book is encapsulating an emotion—a series of emotions—that I felt at a particular time. Each book bottles that emotion up and sets it down on the record. I don’t see myself as anything but as a series of emotions. And hopefully I’ll go through life feeling emotions as richly and as fully as I can, and recording them and transmitting them through these books. But if you were to step away from the books and step away from these experiences, I don’t see myself as a figure. My ability to live goes only so far as I’m able to immerse myself in places and feel places and people richly. And I think if I were to stop being able to do that then I would stop living in a certain way, and stop being.

In this book, Bad News, you move “deeper within the repression.” At one point you travel to an area in the Rwandan countryside where you’re not allowed to go. You haven’t asked permission to go there, so you’re going against the power of the government, and we’re feeling that fear with you, with an extreme sense of curiosity. You arrive at an area of roofless huts, and it’s a scene like out of a tribal war. It feels apocalyptic. I’m wondering if you can encapsulate why the huts were roofless in that village and what happened to the people. What did you see there?

I had heard rumors that people had been made homeless. And I set out with a local journalist to investigate these rumors that weren’t being reported in the press. When I arrived at these villages I found the huts were without roofs, the thatch was on the ground. People were living outside. Some people were living in the few cement structures still in the village stuffed into rooms with goats and pigs. It looked like a war zone. It looked like some great calamity had happened, and yet I could see no signs of a war. I could see no signs of visible aggression. It’s just that the houses had been dismantled. It was completely surreal. And I asked the people, “Who did this to you … was it the army or the police?” And what they said was not what I had expected. They said: “we did it.” What they said was President Kagame almost whimsically had declared that he felt the thatched roofs were primitive. And the local authorities, in their extreme zeal and desire to please Kagame, went out and ordered people to take off the thatch from their roofs. And because people were unable to speak … who were they going to speak to or complain to? There was no one. There was no media, no recourse to justice. The people simply complied with the order; they had no choice. And so they pulled down the thatch from their roofs. And then they asked the authorities, “Now where do we go?” And the authorities shrugged and said, “Well, we’ll have to wait for replacement houses to be built.” It was an education for me because it was a moment when I realized the extent of the catastrophe that is possible when a society cannot speak and when there is no free speech. And this is when I saw the effects of the dismantling of free speech in the country. A society that can’t speak is like a body that doesn’t feel pain. If our body were not to feel pain, we could cut off a limb and we would not know it because we would not feel it. And this is what I felt was happening in Rwandan society. Great harm was being done. And because it was not being reported, people weren’t aware of the full extent of the harm and they continued almost mindlessly sometimes. Because there was no one to cry out and stay stop, this is hurting.

And somehow that story brings us back to Gibson, one of your students who becomes a close friend of yours. He’s really in many ways the heart and soul of this narrative. He’s somebody you point out is interested in the philosophy of Hegel, and how appearances are taken for reality in Rwanda. Can you tell me what Gibson was trying to show you in Rwanda?

Gibson was one of my favourite students. He was an incredibly talented man. He wrote beautifully. He wrote these perfect paragraphs; each paragraph flowed from the other. And Gibson’s story moved me more than some of the high-profile journalists in Rwanda because of our personal connection and also because his actions seemed so benign. He wasn’t trying to take down the government. There was no malevolent motivation on his part, and to be honest, the threat to him was also intangible. There was nobody standing with a gun to his head. It was all phone calls, threats and rumours and the spoken word. And all of these somehow combined, and it was only the moment that Gibson left the country that I realized there was something really powerful here.

I was aware how much Rwandans are attached to their country and attached to their land. It’s a country of many exiles, and there’s a great sort of feeling of repossession of the country and attachment to their homes. And for this man to feel he needed to flee the country and go to a slum in a neighboring state with very little money, it meant that there had to be something powerful at work. And that’s sort of what introduced me to the notion that there was another world in which things were operating that I wasn’t fully aware of. That’s when I began my investigations. Gibson, before he left the country, taught me how to look at Rwanda and how to look at a dictatorship in a certain way. He taught me that we can both see the same thing but have a completely different experience of it. These streets that were Rwandan symbols of progress—that were well paved and that I’d been on many times—Gibson pointed out to me that those roads were empty. And it was true. They were empty, but it had never struck me. Where were the people? They were on our road that was unlit, cobblestone where people could trip and fall, but it was a space where people felt safer because they felt they were unobserved by the state. And so we begin to see that what others see as progress might be seen as entirely different and in an even fearful way by people for whom those roads are built. And again, it points to the importance of free speech. How do we know that the things we’re building represent progress to people? The only way we can really know is when people can speak freely and tell us how they feel. And this is something that is rarely done in Rwanda. People like to speak for Rwandans and say, “Oh, they have nice roads, they have a good health care system, they have this and that. They should be happy,” without asking Rwandans who are unable to speak freely whether those Rwandans would accept the trade-offs that are made on their behalf by the world.

Gibson, at the end of the story—after he flees and loses his mind, loses his identity—strikes me as a tragic hero. He starts off as a sage, trying to tell the truth and showing you what’s underneath. But in the end, because he is punished, he loses his identity. It’s almost as if Rwanda has lost its identity because it’s lost its voice. Is Gibson a metaphor for Rwanda?

I think it’s true that we begin to think what we say. When you are constantly repeating propaganda in a certain part of your mind, you begin to assimilate it and believe it. I experienced this myself in a small way. In the beginning of the book I hear this blast and I go to the scene of the grenade blast. And I can find no confirmation in society of this blast, and so the idea sort of disappears and I begin to question whether I heard it in the first place.

But I’m reluctant to speak for Rwandan people as a whole, because I feel they cannot speak for themselves. So I do feel that anyone who claims that they know what Rwandans are thinking is in some sense arrogant or disingenuous, because how can we know what they are thinking when they’re not free to say it themselves?

You write about Rwanda being “a mirage of a country.” When I read that I took it to mean that what you see on the surface is not what people’s lives are actually like and that the country is built on and fed with propaganda. The propaganda informs Rwanda and shapes our view of it, certainly in mainstream media.

I think it also links to the fact that there is no vibrant journalism. I think the world’s view of a country, more than we think, depends on local narratives. World correspondents depend a great deal on local journalists for their information, and when local journalists are not free or are gone, that void is filled by propaganda. That becomes the de facto worldview on Rwanda. That’s one of the reasons why Rwandan propaganda has become so effective and powerful.

Your book, in a number of places, is an indictment of international agencies and western governments there; you suggest they’re sustaining the repression. What is your opinion of foreign journalists there? There were a number of foreign journalists that lived in Rwanda when you were there and could leave anytime if they needed to. Were they doing the job that they should have been doing?

I think everyone was playing a careful game. Everyone was trying to work out how they would continue doing their job, in an honest way, without getting thrown out of the country. Rwanda presents you with a stark choice: If you criticize the country, you get thrown out.

I remember during the 2010 elections, there was a Reuters journalist who wrote about some of the subtle ways in which the government was controlling voters and telling them to vote for Kagame. The stories were wonderful. Among the donors, however, I don’t think there was much honesty on their part. They knew about all the repression but they chose to ignore it or to raise it simply in meetings with the Rwandan government and then send them a cheque on the weekend. So the financial flow to the Rwandan government never stopped despite the growing repression. And this was a choice the donors made consciously in Rwanda. They chose for the Rwandan people. They said, “You are Rwandan and therefore you do not need to live freely as long as your economy is growing, and you should be happy with this.” And this is something they would never accept in their own countries or for themselves, and yet they were imposing it on the Rwandan people very consciously.

At the beginning of the conversation, you mentioned that these books are in part telling the emotions that you bottled up during your experiences in Congo and Rwanda. There’s also the way in which we deal with these countries and the effect of Western aid policies. I get the impression you feel a sense of responsibility not only to Rwanda but also to the journalists you taught and saw struggling. Did that sense of responsibility drive you creatively?

I guess what drove me was a sense of affection for them and sympathy with them. I became involved in my students’ lives only because I was working with them and knew them as human beings. And the more I knew them the more they became my friends. When they ran into trouble I wanted to help them, and they unraveled this world in which I saw people living very restricted lives.

I do feel responsible for recording some of the things that I experienced and some of the stories of Rwandan journalists because they saw their country was heading in a direction that was wrong or dangerous. They stood up to the government and they suffered for it. And now their names are hardly spoken of in Rwanda because they are seen as enemies of the state. I felt a certain responsibility to record their stories so that these people who stood up to the government are not forgotten, and that we remember that Rwandans did ask for their freedoms, and did ask for freedom of speech, and did ask to be able to speak up about the disappearances and the imprisonments and forced exiles that were occurring in their society. They did try and they were crushed by an incredibly powerful system. That was something I witnessed and I wanted to make sure in my way that these people were not forgotten for their courage and their bravery and for their clarity of vision. They saw early, they saw clearly, and they responded in ways that tried to protect their society.

The book pays homage to a number of people who are no longer alive, such as Andre Sibomana and Charles Ingabire. But you have to tread delicately because some of the journalists you talk about—whose lives are being revealed—are still there and need to be protected. That’s the balancing act, I suppose.

This is a kind of unique book in a way, I think. Most books I’ve read, novels like 1984 or Solzhenitzyn’s work, [with] historical dictatorships that are easy to portray as repressive like Stalin’s or Mao’s, are all written from the point of view of exiles. But this book is describing the underbelly of a dictatorship that still exists in contemporary society and that comes with its own peculiar set of challenges and effects. And yeah, you have to play a kind of balancing act in order to be able to describe that without negative repercussions. It’s something that’s difficult to do.