The first piece of Alana Massey’s writing I came across was “Stop Wasting Your Time on Bad First Dates” from her column on New York Magazine’s The Cut. Her call to action is right there in the clickbait title: if there’s no chemistry, women shouldn’t feel obliged to prolong a date with a man. This didn’t so much introduce me to a concept that had never crossed my mind as it put in crystal clear terms something I had always suspected. The article gave me motivation, especially this line about an encounter with a street harasser: “it got me thinking about the amount of time we spend tending to the feelings of men to whom we owe little more than basic decency.”

Massey’s writing got me thinking about that, too. I thought about all the energy I have spent making sure men in my life were validated: men I wrote about, men I’m related to, even the men whose balls I literally busted for a living. It wasn’t always pretty, the world Massey revealed, as if she manufactured the prose equivalent of the magical sunglasses from They Live. I saw these dynamics in television ads, in the phrasing of other writers’ work, in line in the grocery store and buses and subway trains. I recommended Massey’s articles to friends not only because I think they will enjoy her witty prose but because I thought it would help us all to see the world in a way that would benefit us.

When I learned Massey had an MA from Yale Divinity School, I started to think of her essays as sermons. I’ve always looked to literature rather than religion for morality. Unlike many sex and dating columns, which can slip quickly into myopic complaining, Massey’s work has a clear, unsentimental idea of how to be good (and as every great pontificator should, she makes herself vulnerable by describing the times she does not take her own advice). Massey’s writing revealed the ways I could cease catering to entitlement and just go home and read a book.

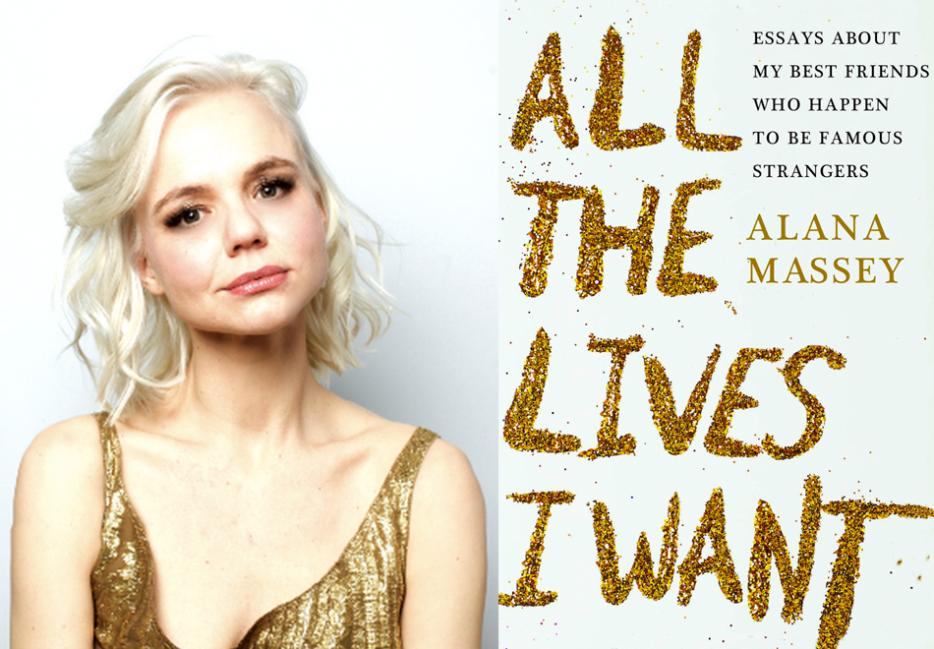

If you’re looking for something to read the next time you say no to a second drink with a boring date, you couldn’t do better than Massey’s new book, her first, All The Lives I Want. This collection of essays, some previously published online, some brand new, presents a pantheon of famous women. Massey uses Britney Spears to talk about bodies, Lil' Kim and Nicki Minaj to critique public faux competition, and Anna Nicole Smith to discuss class ambition.

She takes personal, often unpretty personal stories, sticky with memory, and sprinkles them with sparkly, relatable pop culture. What emerges is not a crafty mess but a clear construction of language and meaning, just like the gold glitter that spells the name of her book on its cover.

Tina Horn: All The Lives I Want struck me as a very moral book, in the sense that it has consistent principles and calls for us to do better by our iconic women. You identify a whole lot of sexist hypocrisy in media and culture, for example. Reflecting on the fact that you have an MA from Yale Divinity School, I began to think of these essays as almost pop sermons. I wonder if you think of them that way?

Alana Massey: I've never had my writing described that way before, but I like it. I think my writing has been deeply informed by having a religious education. The Bible is a book dense with blood and bones, angels and architecture. It is often really stark in its visuals and metaphors, and I think that can lend itself to writing that reads like parable. Except in this case, it's The Parable Of That Bitch You Thought You Could Sleep On, in several variations.

I think that Christian moral teaching is often about seeing the unexpected in a story, getting thrown a moral or ethical curveball that challenges your preconceptions, the shape of the lens you see the world through, and that's something I do want to do here.

Your book may represent a gospel I could really get behind—one that constantly reminds us not to put up with bullshit from men, for example.

If I was doing apocryphal Gospel writing, I'd surely emphasize that no bullshit from dudes element.

An example of moral teaching from All The Lives I Want is in “Being Winona; Freeing Gwyneth” (which was originally called “Being Winona In A World Made For Gwyneths” when it was published on BuzzFeed in January 2015). It would be captivating enough just to call it, “Are You A Winona Or A Gwyneth? Take This Quiz, Find Out!!!” Instead, you transform an identification with resentment into an opportunity for forgiveness.

I found myself trying to figure out a way to elevate these women and reimagine their legacies without necessarily shitting on their opposites or those who may be set up as such.

Right, because that's just replicating the problem. Can you say more about how that piece changed from web to book?

The one that ran on BuzzFeed gives a perfunctory nod to Gwyneth as having her own kind of loneliness and pain. But I was less than six months off of the relationship that inspired the essay so it was added by my grudging best self. I had to labor to be kind about it. When I revised the essay for the book, for both technical reasons and some element of having grown out of my antagonism for the Gwyneth Paltrows of the world, I was able to be gentler, more open to her.

I think it also had to do with dying my hair blonde and becoming more successful in the time between publishing it and finalizing the book.

I wrote this about Gwyneth last year.

The Winona/Gwyneth piece went viral, leading to you getting signed to an agency, which led to the sale and publication of your first book. What did it feel like to revise it?

I was really happy to do it. I wanted it to fit within a broader story of forgiveness, both of others and of ourselves, and that had to include kindness toward the people I had sort of cavalierly dismissed in the first version.

It strikes me as such a wonderful possibility of the form of the essay that it can be a living document as you grow as a human and a writer.

Yeah, I feel like it is rare that you get to see a piece of yours grow up with you. To graduate from webpage to paper with a new outlook on it too. Now I'm getting nervous that I will want to revise ALL OF THEM in the future.

Well, that's the blessing and curse of a book. At a certain point you have to accept what you can and can’t include.

That was something that I went through all year between finishing and publishing, some new thought or piece of news would come out on one of the women in the book and I'd be like "DAMMIT I NEED THAT!"

Another example of the morality that exists on a prose level would be an assertion like this one from the Anna Nicole Smith chapter: “We demand that socioeconomic migration be permitted only if the traveler promises to adopt enough white middle class values to reaffirm that we have chosen virtuous ones.” Obviously, creating this kind of reasoning is an intellectual and political project. I’m wondering if you had impulses with writing the book to create something that tells the world how to be good, or how to be better, anyway.

I don't think that I have a decent enough record of goodness and non-judgment to have made that my explicit project but I do feel compelled to hold up a mirror to ourselves, our society, our values and say, "Look at us. Look at what we have done and said that is a source of pain and hypocrisy." At the same time, I want to hold a mirror up to ourselves and say, "Look at what the world has done to us. Look at what we really are. They have said wrong and done wrong by us." I want to make myself culpable and redeemable in both of those stories.

So I feel like the zeroing in on forgiveness, both of self and others, was what I felt most drawn to when exploring these women's stories.

You make the connection between the way the movie Lost in Translation treats Scarlett Johansson’s character Charlotte and the way the media treats Scarjo the actress, the person. Both of those things had bothered me, but your book feels like a playbook for discernment as well as a call to cross our arms over our chests and say BOY BYE to all of it.

I recently reread the whole book aloud for the audiobook and found myself wondering, like, "Wow, Alana. Maybe you're overreacting." Because I do end up being so harsh about how pathetic Bob is in Lost In Translation or how the boys are in Virgin Suicides. But I think that pushing back on these characters who we have so unquestioningly valorized and considered protagonists requires more than a push, it needs something of a shove to restore equilibrium. So I feel like if going hard and definitive rather than watering down my critiques of these man-centric narratives makes me seem shrill, it’s a price I can handle paying.

Well, you're not talking about real people that deserve diplomacy. You're setting up a critical arena in which to test these fictional male characters against a revisionist reading of the female characters. Based on your own critical criteria, the men just don't hold up. The men in this book damn themselves, you just catch them red-handed.

Right, I think there is such an aversion to the hard evidence against really troubling and sometimes dangerous men. We trip over ourselves to make up fictional reasons that excuse their behaviors instead of just swinging Occam's Razor and realizing, "Oh right, this person does enough bad things that they can safely be called a bad person."

You're also guttingly honest (especially in the Joan Didion piece “Paradising”) about how hard it can be to follow your own advice in your nonfictional life. You are hard on real men like your ex, James, too, but only by honestly describing what he said and what he did.

In the Joan Didion story, I sort of let an ex I talk about, James, off more easily than I could have because the gruesomeness of some of the things he said and did were things that didn't fit well stylistically in the story.

It was important that an essay that was about personal mythologies around Joan Didion at least aspire to write with some of her artful restraint.

In the title essay on Sylvia Plath, containing the excerpt from which your book gets its name, you have the following quote which I basically want to make my email signature: "Glitter is the unbridled multitudes of shiny objects that have no predictable trajectory and no use but their own splendor." Your book cover, which I love, has the appearance of gold craft glitter affixed to the title with Elmer's glue. This is such an excellent encapsulation of this book, I think: the elevation of things dismissed as girly to sublime heights. What do you love about glitter?

I am really happy about the cover and not only because it was my idea, down to insisting forcefully that it be gold glitter on white. I wanted it to be a bit of an homage to the kind of fan poster that I might have made in eighth grade to hold outside of Total Request Live for a favorite celebrity. I’ve always hated that cliché about how all that glitters isn’t gold, because it is a way of degrading something that is adjacent but not identical to the thing we’ve deemed valuable, is a fraud of some sort. There are all sorts of things that glitter that are still worth our while, and more accessible and frankly, way fucking cuter than the top-shelf shit.

I was also pleasantly surprised that the cover came back looking kind of like exceptionally fancy lines of cocaine! Though I do try acknowledge throughout the book that I don’t actually know these women, there is something a bit audacious about me calling them “my best friends who happen to be famous strangers,” in the book title, even if it is tongue-in-cheek. Cocaine elevates our sense of self-importance and also increases our sense of intimacy with people we barely know, not to mention that it is a bit dangerous but still very appealing and seductive. So that there is this innocent girlish meaning and this sort of nod to the vice inherent to celebrity worship makes a lot of sense to me.

In that same essay, you "show your work" of investigating meaning in Plath through Etsy, GoodReads quote pages, eating disorder blogs, and Tumblr. Your investigation here is more lively, varied, and crowdsourced than the traditional nonfiction investigation of texts. Do you foresee a future of the art of the essay in which knowledge, taste, and consciousness are informed by the annals of the internet, which in many cases does not involve self-conscious participation in one kind of transmittal of thought?

I feel like there is a shift toward more thoughtfully engaging user-generated content online and investigating it for meaning and nuance and stories, instead of just regurgitating it for news in tweet round-ups and “best of” lists. I mean, I was a staff writer at BuzzFeed making those round-ups so I’m culpable in having used that content in a way that was less than sophisticated but in that job, I learned how to dig around the internet in a way that I would like to see done in more ways. Katie Baker is a journalist who has done that really well, particularly in this story about Facebook vigilante crime fighters trying to find the murderer of a teen girl. Journalists like Doreen St. Felix have also brought to light the very important point that mining the internet for content can be hugely exploitative, particularly for young Black creators, and that there needs to be a serious conversation about the uses and misuses of online content.

How do you decide what subjects to choose for your essays? Is this always on your mind when you're seeing a movie or listening to music or reading?

I really don’t actively seek out thoughts for these kinds of essays. They were a pretty new territory for me but once they started coming, I couldn’t stop them. This book could have been twice as long based on the list I wrote of “famous women we’ve done wrong by” but I selected women I felt I had enough knowledge or original insight to discuss through the lens of how they’ve been misrepresented or not given their due somehow.

Do you follow pleasure? Wonder? Obsession? Are you more likely to write about something you love or something that pisses you off?

I think in the cases of all of these essays, the primary emotion I was following was anger. I am angry that we have dissected Britney Spears’s body over and over again for nineteen years. I am angry that we subject Mary Kate and Ashley to cruel speculation when they didn’t ever choose fame. I am angry that Lil' Kim isn’t recognized by a lot of the mainstream as a trailblazing genius. But I think that the anger always comes from an initial affection that isn’t based on feeling sorry for someone so much as feeling connected to them and the element of their work that is being ignored in favor of cheap shots or worse, the silence that comes with being unacknowledged as someone critically important to our culture.

Those of us who have done sex work, who explore our own experience in sex work in our writing, have a lot to grapple with. In many cases, we find ourselves in the sex work version of the Virgin-Whore dichotomy, that we either have to be Happy Hookers or confessing victims. Your portrait of working as a stripper toes that line: you're certainly not like our friend Jacq the Stripper, whose writing can basically be summed up as stripping is entertainment and we’re fucking amazing so bite me! You do admit more or less to being low on choices when you return to stripping in the Amber Rose essay; you show the ways it made you unhappy, that strip clubs might be corrupt.

The first time I ever mentioned my sex work history in writing under my own name was in an essay for Pacific Standard that was entirely about watching deaths happen online in various media formats since I was a young teen. I intentionally folded a very brief anecdote from a club job into the much bigger narrative about my own relationship to mortality. I did that partly to dip my toe in the water of being “out” and seeing how readers, friends, and family would react, but I was mostly doing it to demonstrate that sex work stories are part of otherwise very complicated human stories that do not have sex work as a focal point if people telling them don’t want them to be.

At the same time, you’re not looking for absolution. You talk about the wisdom and art gained by stripping. You follow Rose's lead by demonstrating neither "repentance nor denial." What informs your decision to include stripping in a book that isn't only about sex work?

I chose to include it because Amber Rose met the criteria of being a woman whose treatment and whose story have been truly inspirational to me and have informed how I see celebrity, sexism, and erotic labor. The fact that stripping was a part of that wasn’t going to be kept secret. I casually reference having had a sugar daddy in the Courtney Love essay and then move on because it wasn’t super integral to the story I was trying to tell, but being a stripper who didn’t want to be stripping was critical to honestly writing the essay about Amber Rose. I think that any book or story that is “only about sex work” isn’t a very good story because all sex work stories are also about money, gender, race, power, desire, expectations, capital, fantasy, and reality. Even the really short ones.

Here’s an obligatory 2016 US election question: In "Run the World," you do this spectacular thing where you describe dancing at work to “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” by Tears for Fears and “Run the World” by Beyoncé, using this to describe the difference between women and men's relationships to power. This instantly made me think of Trump’s autocratic approach to governing and all the ruthless unapologetic misogyny involved, compared to HRC's invisible labor. Do you think that some Americans want to be ruled by a man rather than run by a woman?

I tweeted this last June and I still stand by it. Only it is a lot more than just Sanders supporters who claimed they went with Trump (which I don’t think that many actually did) who would prefer a man to humiliate them with his authority than to allow a woman to even have authority. The expectation for women to play supporting roles in men’s hero narratives runs deep in this world. I’m ready for those narratives to fuck right off.