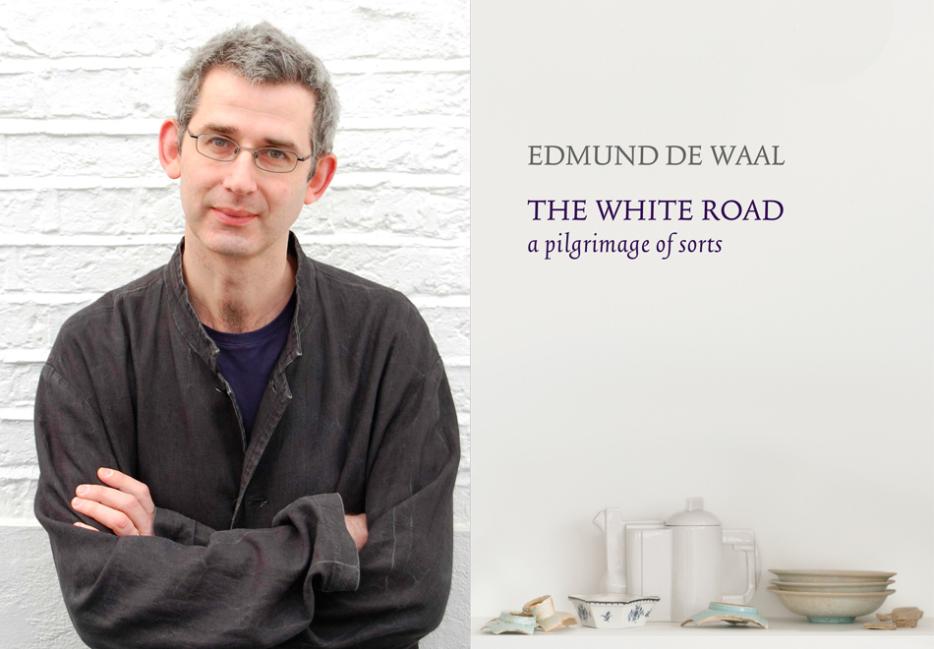

Edmund Arthur Lowndes de Waal, OBE, is that cultural Sasquatch, a successful artist and writer. The two fields are curiously incompatible, the way the noble gases are—visual fluency so often seems to butt up against linguistic expression, and vice versa. But here we have de Waal, who is not only a decorated creator of both nonfiction books (his 2010 debut, The Hare with Amber Eyes, won the Ondaatje Prize) and ceramic sculpture, but whose talents offer mutual support, the art instilling in the writing a degree of poetic abstraction and the writing tethering the art to a grounded historical viewpoint.

Talking with de Waal is an enjoyable exercise in border-hopping, much like his new book, The White Road, an investigation-travelogue-memoir-history of his lifelong experiences with porcelain, his chosen sculptural medium, across China, the United Kingdom, Germany, and the United States. That the book is indefinable doesn’t make it difficult—think Sebald but with less awestruck melancholia, or the most imaginative art history professor who ever taught. What allows the reader to follow easily through meditations on alchemy, poverty, creativity, and even the ravages of Nazism is de Waal’s voraciously curious voice tugging us through his musings, always patient, but equally excited to move on to the next episode of material history in his notebooks.

We spoke over the phone about the junctures between writing and art; de Waal’s sources of inspiration for his unorthodox creative practices; and the curious grip of ceramic passed from hand to hand over the centuries.

*

What was your impetus for writing a book about porcelain, coming as it does out of your artistic medium?

This is a book that comes out of a need to really work something through. I’ve been working with clay all my life, since I was a kid, seriously working with it for forty years. I’m in my early fifties now, and there is a sort of compulsion to really see whether I could actually get to the root of why I was still using this particular material and what that personal obsession actually really meant. It’s a very, very personal book.

The format of the book strays through memoir, historical writing, and even reporting on the current day.

I hate being corralled by genre so this is in no way a cultural history. It’s certainly not connoisseurial. It’s a kind of autobiography, an attempt at recovering particular people who have been lost to history. It’s an attempt to make a particular kind of encounter with different geographies, different places, vivid. It’s some kind of meditation on the color white, as well. That’s a crap answer to you. To be honest, I don’t know what it is at all anymore.

There have been a few books lately that are collage-like, like yours—they move through different formats and genres. Critical and autobiographical books come to mind like Ben Lerner’s 10:04, Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle, and Heidi Julavits’s The Folded Clock. Are there particular writers you look to in terms of how you encounter these different formats in your writing?

The way the book is structured is in fragments. It’s sixty-six short chapters, and a series of journeys as well—some of the chapters are little more than fragments. Given that a lot of the book also comes out of the experience of being in libraries or archives, the people who matter to me are obviously W.G. Sebald and Walter Benjamin. With Sebald, the past and the present moment are so totally intertwined that you move in narrative without really noticing how he does it, and that’s an extraordinarily vivid ability. And with Benjamin—it sounds profoundly pretentious but it’s true—what Benjamin does is bring the physical world of objects into fantastic proximity, he just gets the aura of objects and people who own them and collect them. Those are the people I care about. God knows I don’t even begin to go anywhere near them, but they’re the people I love.

You’re already well known for both your writing and your art, but is it intimidating at all to take on those kinds of comparisons to iconic writers?

Of course, absolutely, but then, I’m not remotely claiming kinship with their kind of writing; you just have to be open about the kinds of things you care about. There’s a whole kind of writing about materials and about objects which we haven’t really opened yet, which is just beginning. There’s been so much sedated writing around objects or writing by collectors or connoisseurs or museum-y people; there hasn’t been passionate journey storytelling around the things I care about.

Throughout the book, you refer to yourself writing and taking notes, then you refer back in time within the sweep of the book’s research, to several years before. Do you write these sections right after they happen, or are they remembered later?

A lot of it was written when it was happening, at night in Jingdezhen [China] or in Meissen [Germany]. I haven’t got a very good memory; I need to write as I go. Lots and lots of editing goes into it. That’s when the work starts, because traveling and researching and walking in other people’s footsteps isn’t really work, it’s just totally joyous, immersive stuff, and writing books is bloody hard work. You can write as many notes as you want along the road just so you remember sounds, you remember a particular smell or a gesture or how someone smokes a cigarette—all that’s really, really important, but then when you write a book, you write a book.

Throughout the book, you do have a way of bringing objects and their intertwining relationships to life. How do you accomplish that?

You put aside any sense of having to do a complete history, of trying to tell the whole story. This isn’t the history of porcelain; it’s my journey through my obsession. The reality is that by electing to pick something up, by choosing to go to a particular place and encounter something, just thinking about this vase in Dublin, or this Marco Polo cup in Venice, or something in Dresden—as soon as you’re in conversation with a particular object, then I feel a ridiculous responsibility to keep going until I can work out what it means, who made it, what the cost of making it was.

The book is built out of objects and places. You include the historical trademark seals impressed into the porcelain in your section dividers. In the writing, there’s a heightened sense of the texture and feeling and atmosphere of these specific objects. Does that sensitivity come out of being an artist as well, having worked with these materials for so long?

It’s like anything. If you talk to a musician who’s spent forty years with a viola or something, they have a sense of being able to listen to pitch, to timbre, extraordinary things that we can’t even begin to discern as non-musicians. If you handle objects all your life, then you begin to pick up different things.

You’re the rare example of an artist and writer in one. So many artists I know might not be very sensitive writers, but they do have these particular feelings that they want to express—they understand paint or sculpture so deeply but don’t necessarily have the ability with language to express that, as you do.

For me, art and words, they’ve been parallel parts for such a long time. I’ve always read poetry, I studied English at university, after I was apprenticed. But what’s been different for me over the last ten years is I put down a whole way of writing, an academic patrician way of explaining things about objects, just contextualizing them, telling people things. I just thought, fuck it, I don’t want to tell anyone anything, I really just want to work it out myself, what it means to pick up an object and have it in your hands, have it in your life, pick it up, put it down, come back to it. What happens when you do that, and, critically, what kind of storytelling can you make possible out of an object, how much can it bear without it being precious and overweighted.

Do you feel you have certain goals that you’re looking toward in writing that are different from what you’re looking toward in making art?

One practice doesn’t map the other. I’m not trying to make in porcelain a narrative—I’m not trying to make a narrative that I’ve written in my new book. Similarly, I don’t try to write to explain my pots through words. So there are real and genuine synergies between the two kinds of practice. There’s also a shared ambition. I struggle with this because I’m so bloody English, to say this out loud—I really want to push myself as a writer, I really kind of want to find a way of capturing the experience of a particular kind of reading that I care about. Which is often quite slow. Which is sort of what I want to do with my pots, too: slow people down, make people look again. I’m trying to do both those things in different ways; they’re not the same, but there’s a shared bit of DNA there.

There are other visual artists who share your kind of literary sensibility in their work, like Josiah McElheny or Anselm Kiefer. Their medium is not just the visual nature of the objects they make but also the narrative nature of their material, its historical references and forms. Do you feel a kinship with that?

That’s absolutely true, but I also feel an odd kindred with Cy Twombly, this idea of mark-making and writing within the art, or indeed Ed Ruscha, crazily. The idea of the word being an object, that seems to me to make so much sense. And to be so beautifully provocative and close to poetry, poetry in all ways. How do you do it, how do you do it, how do you do it?

In the book, you engage with the formal qualities of the porcelain, its aesthetic presence, but also its historical and social context. You do both those things at once, which is very tough.

It is tough to do, but you know what, the weird thing is that there’s a real coherence, a melding together of different tenses in my material. So when I’m making something, I’m completely in this beautiful, transient present tense, it’s absolutely about the moment, and simultaneously it is powerfully in several other much more complicated past tenses, of historical present. When I’m writing the book I’m trying to both be alive to a whole narrative of the present day, and my own journey and my own encounters, and also create a really engaged historical context for the whole thing, to talk about Jesuits, or optics, or colonialism, or the Nazis—whatever it is, to be able to do that simultaneously. It’s worth trying.

Similar to how you describe the objects, you have a way of making historical figures come to life. You engage with them deeply and imagine what their interior monologues might be. In a historical research sense, do you feel okay going that deeply into a character and a personal life rather than approaching it purely academically?

I don’t give a stuff for the academic in one way, and of course I do in another. I’m a passionate believer in good research but for me the research is somatic. You go to the archives, you pick things up, you follow people up mountains, you try to work out what they’re eating. That’s all good dogged research, but at the same time it does allow you a kind of portal, a kind of possibility, and to reimagine, to allow yourself to write a possibility of what someone might be feeling or thinking. It’s a profound affront to lots of historians to do that, but I don’t give a stuff, because actually a lot of historians don’t bring people back to life. They keep them in their coffins where no one can touch them, in a great carapace of academic rigor. I’m not interested in burying them, I’m interested in bringing them back.

Through the book, we meet these people who are working with porcelain in a similar way that you do, all trying to understand the material and its scientific and creative limits.

What I’ve done is I’ve chosen various avatars. There’s François Xavier d'Entrecolles the Jesuit, Tschirnhaus the mathematician, then there’s William Cookworthy. They’re all people for whom porcelain is a question—it’s a kind of query about the world. It’s not a given. So in choosing all those people, what I’m doing is returning to beginnings, going back to the start again, because that’s what it’s about, going back and starting again. There are lots of people I could have chose who make porcelain who I have absolutely no interest in at all.

The book is also an aesthetic object in itself. You divide your writing into these short, staccato sections with extravagant, visually distinct chapter breaks, and there are also quite a few images throughout the text. What was the design process like for you?

The design process was very significant for me because I wanted to make a book that had a lot of space in it. I can tell you that’s quite a big ask for a publisher, for a commercial book. My feeling into it was very, very parallel with the way in which I construct my installations—to find more space as I make them. I put work out there and put things away until I find a place with the porcelain where something comes right, and you’re drawn through the artwork. But you can also pause.

So that’s what I wanted to do here, was make a book you wanted to keep on reading but had enough space for you to slow down as well. I worked with a fantastic graphic designer called John Morgan, who I work a lot with. And then you’ll notice that there are no color pictures or photographs in it, because I hate art books, and I wanted the images to just be seamless with the book—to encourage you in the book, not to illustrate.

I got so told off last time when I wrote the last book because I didn’t illustrate any netsuke. I said, “Well, why should I illustrate them? I’ve described them in the book, wasn’t that enough? What do you want, color pictures?” When I read a book I don’t necessarily want big glossy color photos in the middle of a book; what I want to do is read a book.

Both of my parents are ceramicists. They had a potter’s wheel and everything in the house, though they didn’t practice so much because they’re ceramic engineers. But growing up around that, you tend to notice the quality of glazes, the ceramic materials around you. It’s an area so many people overlook.

It’s embedded. If you’ve had that as a kid, that’s there forever, isn’t it? There are whole cultures, in Japan and China and Korea, where the sensitivity is present all the time. The taxi driver would start talking to you about pottery or something extraordinary. Part of my current life mission is to rescue this stuff from being thought of as precious or esoteric, because it isn’t, it’s fantastically immediate and interesting and engaging and possible to make real.

What makes a good piece of porcelain or ceramic an aesthetically successful pot, in your opinion?

I was in the Metropolitan Museum on Monday, handling a piece of early Chinese porcelain. What was so extraordinary about it was that it felt unresolved. It wasn’t so perfect that it had no space for me to feel that it was still being made; it still felt it was becoming something. The very best kinds of object for me are the same things I look for in any art, which is a way in to something, where you feel someone’s thinking and feeling and sensing and exploring simultaneously. With porcelain, that’s to do with balance and translucence, to do with working with or against purity, to do with some kind of sense of symbolic function, all those things coming together, but it not being too perfect.

The viewer or the holder always completes the object.

I agree. When it comes into your hands, at that moment you are obviously in some kind of connection with the person who made it. It’s not the end of conversation, it’s not the beginning; you’re in the middle of conversation.

In that context, trying harder doesn’t always mean it’ll be right. There’s a serendipitous moment when you know you’ve made something true or good.

The strangest thing is that what you sense to be something that is truly alive and you feel is communicable with someone else, they might totally hate it. Just not get it. Sometimes it doesn’t work for all the reasons that porcelain doesn’t work. It’s a material that’s notoriously tricky. Sometimes it doesn’t work because what you make is just not good enough. It looks okay, but okay is nowhere near being alive. Okay is not the point. Why make okay stuff, why write okay books?