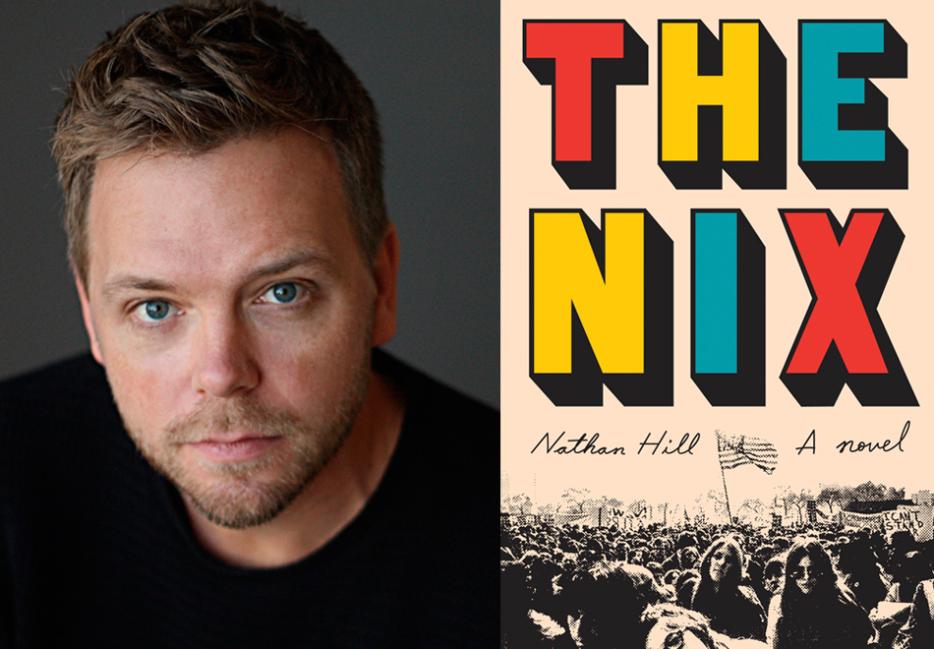

On October 6, John Irving sat down with Nathan Hill to discuss Hill's satirical debut novel The Nix at the Harbourfront Centre in Toronto as part of the 2016 International Festival of Authors. Here is their conversation, lightly edited for clarity.

John Irving: I met Nathan Hill in January in Oslo. I don’t recommend Oslo in January. But I was there for the Norwegian translation of Avenue of Mysteries and my editor at Gyldendal Norsk, my Norwegian publisher, happens to be Nathan’s publisher for The Nix. And she invited us to have a dinner together. I was struck at the time by how much of a buzz there already was about this first novel. It didn’t happen to my first novel. It didn’t happen to me until the fourth novel. Nor did I have a single foreign translation until that fourth novel. But Nathan was already finding success with translators, some of who are my publishers as well. We have the same Dutch publisher in common, and as it turns out the same Canadian publisher. I was very happy to meet him. I found it incredibly encouraging as I told him at my age, 74, when I see a decline in the appetite for literary fiction in our culture as a whole in North America—more of a decline in the US and the UK than I notice in Canada, but a decline everywhere nonetheless. I found it very encouraging that this could happen to a young, literary novelist today, especially because I’d already heard that the novel was long. Yes, it is.

I was back in Toronto, very busy working on a teleplay, and Nathan wrote me and asked if I would look at his novel. And I certainly said I would. I’d liked him, I wanted to support a new fiction writer, but I said I was very busy right now and didn’t know if I’d get to it. The truth is, what I do in those situations hasn’t changed for a number of years: I take my assistant, he or she, aside, and say, OK, you read this book—enough of it to know if it weren’t your job, you would keep reading. Or enough of it to know that if it weren’t your job, you wouldn’t keep reading. You get to that point, you can stop reading and tell me, “You should read this book, I’m going to finish it whether you want me to keep reading it or not,” or you tell me, “I wouldn’t keep reading this book if it wasn’t my job.” But my assistants know me better than that. They know that if they say, “I think you should read this book,” and I hate it, I will make their lives miserable. So when they err as they have erred in the past, they tend to err on the side of, “No, I actually am liking this book but I think you might hate it so we probably don’t want to read it,” or words to that effect.

This was very different—long novel though it was, my assistant Bronwen brought it to me. She had read not much more than half of it. She said she was going to keep going and would I give it back to her sometime soon please. That was an early indication. But she’d done something that I hadn’t asked her to do. She had marked two or three passages and she said, you read these passages, just these passages, and if you like them that’s why you'll like this book. I read only one passage and I went to page one and read the book. And Bronwen waited a long time to get it back. Because my work schedule is such that the only reading I do is on my treadmill. And this book looks like crap because of the number of times it fell off the treadmill. It is a thick book to fit on the little lip of a treadmill, especially when you crank the treadmill as I do up to a steep incline. So not only did the book fall off the lip but I stepped on it a lot. But I read every word of it, I loved it and I knew I had to write something about it and I wanted to be here to introduce Nathan to a Toronto audience tonight. In my opinion he is the best new writer of fiction in America. The best.

Nathan Hill: I’ve never been so happy for someone to step on my book.

John Irving: In the early going of this novel we don’t like the character of the mother very much. We’re pretty much on the protagonist, poor Samuel’s, side. There are cruel ghosts haunting Samuel, more than one, and his mother is more than a little crazy. My first question to you is where did your love of dysfunction come from? This is not only a story of a mother and son’s dysfunction, but there is a national and political dysfunction at work in this novel as well.

Nathan Hill: Dysfunction makes for really good fiction. I was writing this book in, the lions’ share of it, 2008 to 2012-'13, and it was a time in the US where everyone was saying we were more politically polarized than any time since the Civil War. I had all these ghost stories in the novel already. I had this character who came from Norway and I had the story of the house spirit, the story of the Nix, and the story of the Nix just seemed very profound to me at the moment when I was writing this novel. This idea that the things you love the most could someday hurt you the worst. It seemed true for a number of characters in the novel.

Samuel’s, of course, is his mother disappears on him. And so he’s of course undermined by the person you’re not supposed to be harmed by, your mother. There’s a sister who’s disowned by her twin brother. She’s also a musician, a violinist, who, if you know any violinists, has a kind of scar from her violin on her neck. And it got me thinking about the story of the Nix again: the things we love the most can sometimes be disfiguring, such is our need for them. There’s a workaholic in the novel who is swindled by the company he has devoted his life to. There’s a college student undermined by the devices that give her life meaning. There’s a gamer who is betrayed by the very video game he’s obsessed with. And so it struck me that the story of the Nix was pretty universal for all of these characters.

But I was also writing this during our great recession, which was in part caused by the things we thought were so safe they were eventually risk-free. Things like mortgage-backed securities, AAA-rated sovereign debt. The retirement that you’ve been working all your life for suddenly gone in a flash. And so one of the things I was thinking about was that kind of economic anxiety that was happening in the country while I was composing the novel and it seemed to be that, yeah, the reason why the financial crisis was a crisis was because we believed that things were so safe as to be risk-free. We thought they were too good to be true, so the housing market could never fail, you know, and so I guess that helped me connect the personal stories with the political, it helped me see what’s happened between this mother and this son is happening writ large in the rest of the country.

John Irving: I totally agree that the confluence of the personal and the political are not only working to the novel’s advantage but it’s by the time you’re two, three hundred pages into it, it’s hard to separate which of the two dysfunctions is more compelling, because these characters are so well drawn that you’re drawn to them as you are by the best fiction. But the reminders of the political reality you live in and have lived in are so real that it’s in a good sense almost not like reading a novel. When I asked three women readers of The Nix, ages respectively 62, 39 and 32, what they most wanted to ask you, all of them asked essentially the same question. It’s a question about political activism, I think—I’ve reworded this my way but all three of these women came up with this: What does this novel tell us about how the radical left in the US is doing? How have we changed the radical left? Or have we stayed the same?

Nathan Hill: I know that when I started writing the book in 2004, back then I was in my mid to late twenties and was very politically aggressive and I was just insane with anger that Bush and Cheney were elected for a second term. I couldn’t believe it. I was living in New York City at the time and nobody I knew would ever vote for that guy and yet he won. That victory, I don’t know, it made me reevaluate myself. I was living in, we didn’t have a name for it at the time, a kind of social media bubble. Everybody I knew agreed, we all agreed with each other. We were just echo chambers for each other. And I hope what I tried to do both in my life and with this novel was try to get out of that echo chamber and try to see a larger diversity of opinion, especially those opinions I tend to disagree with.

As for the political left, I don’t know, I think it’s hard to say whether they’re more left, more or less successful. There are certainly successes. Shell Oil recently decided not to drill in the Arctic and that was in large part a response to pressures by far-left environmental groups to prevent that from happening. So there’s some successes out there. But I also know that a lot of people who were involved in Occupy Wall Street feel like that wasn’t a successful movement, that it could have done better. I look at war protests, specifically—the book contains two generations of war protests: 1968 in Chicago with Vietnam and 2004 in New York with Iraq. And there was a robust protest of the Iraq War that then kept going for another six, eight years. So you look at that and you think, well, it’s a failure. And I feel like [there's] a perception gap between protestors and what you might [call] folks in the mainstream, that the folks who will go and protest a war or protest drilling are sincere in their beliefs and well-meaning and really, really want to change the world for the better. But that isn’t necessarily communicated to the rest of the world. Oftentimes people are very easily caricatured. I remember when I went to the 2004 protests at Madison Square Garden there were people who had papier maché George Bush dolls dressed as Hitler and you’re just like, how is this helping?

I guess in the novel what I wanted to do was instead of going with my first impulse, which was to try to very sanctimoniously say who’s right and who’s wrong, I realized that I wasn’t the person to be able to make that judgment. What are the odds that in my very narrow point of view that I’ve discovered the truth about American politics? It’s probably very little. It’s zero. And so instead what I tried to do in the book is to examine what it felt like to bump up against politics, to bump up against in a kind of human emotional way, to bump up against historical moments. So that’s why, when I write about 1968, I don’t include any of the characters who are the figureheads of the movement. Instead I was focusing more on the people who were in the background, you know.

John Irving: The exception being Allen Ginsberg.

Nathan Hill: Allen Ginsberg, right, who was there, was a kind of peacemaker.

John Irving: He was trying to keep the peace, whereas I think you’d agree that Tom Hayden and the folks at SDS probably still don’t think they had anything to do with Nixon winning the election.

Nathan Hill: I know that one of the things that I thought in 2004 was that the protests felt a little mediated. It felt like we were there and always thinking, what do swing voters in Ohio think of us right now? And so my impulse was to say, well, the folks in the ‘60s were way more authentic, and I believed that until I actually started researching and I saw that, for example, they nominated a pig for president in the Chicago ‘68 protest because they thought it would get headlines and it did—it was just as mediated as it is now. And then I got to thinking, well, why is authenticity the right metric for measuring a mass movement anyway? So as soon as I realized I was wrong on so many fronts I started pulling back and pulling back and pulling back until the book became more about its characters than about its politics, which I think was a very good move.

John Irving: Just so you know that you’re not the only writer who’s wrong, I remember feeling very strongly in the Vietnam years, especially after 1968, that I would never again see my country as divided as it was then. Wrong. I think everyone would agree the US is much more divided today and about many more things than we were divided, in the latter years of the Vietnam War, about that war. You just used the word sanctimony. Your character Periwinkle has this to say about sanctimony and America: “It’s no secret that the great American pastime is no longer baseball. Now it’s sanctimony.”

Well, you’ve heard me say before I think that Periwinkle is half-right. But the Salem Witch Trials happened before baseball. It strikes me that the Puritans in America predate baseball by quite a lot. You, and Nathaniel Hawthorne before you, know that Americans are sanctimonious. Is that sanctimony connected to the bully patriotism that those of us living outside the United States and seeing how our country looks to those abroad feel very keenly? Is that sanctimony manifest in a kind of uber nationalism that makes both of us cringe? Where does it come from, and how conscious were you of the fact that there are many sanctimonious characters in this novel and many of them wear political clothes?

Nathan Hill: I went to the Wild Card game the other night, Blue Jays-Orioles, I was in town and was like I’m not going to miss this, I’m going to watch this …

John Irving: I thought you were the guy who threw the beer can!

Nathan Hill: No!

John Irving: I texted you in the middle of the game. I was watching on TV and I said, was that you? Did you throw that can? Because as people are saying to me all the time, it is just a kind of stupid thing that happens in your novel.

Nathan Hill: My seats were not that close.

John Irving: That’s what you said. You texted back and said, not me, my seats aren’t that close.

Nathan Hill: And it’s true that in the seventh inning I was happy not to hear “God Bless America.” Whenever I go to a baseball game in the States that’s what they play in the seventh inning, and then they play “Take Me Out To The Ball Game.” And it always makes me feel a little weird.

John Irving: And you can’t escape it.

Nathan Hill: Yeah. The kind of American exceptionalism …

John Irving: Are you tired, too, of the passing jets that fly over stadiums?

Nathan Hill: The show of military force. It creeps me out a little bit.

John Irving: Me too.

Nathan Hill: I was connecting it to kind of nationalism and patriotism a bit in this novel, but I was also connecting it to this this feeling I was having that, because of social media, the Internet, our phones, we have at our fingertips a lot of information. Maybe it’s only natural, maybe it’s human nature, but we tend to render a verdict on something very quickly. We give something our attention for maybe fifteen seconds online and we’re like, well, thumbs up or thumbs down. It’s very, very fast.

If you’ll permit me a weird answer about nanotechnology for a moment: There’s this amazing study the Yale Law School did, where they were asking people questions about nanotechnology. Now, the study, the researchers didn’t care about nanotechnology. They wanted to see what people would have to say about it. They picked nanotechnology because it seems like one of those issues that no one knows anything about. And so they’d say, are you pro or against nanotechnology, without giving anybody any information, and of course the results were all over the board, unpredictable. Then they gave people about two paragraphs worth of information about nanotechnology, and once people had just a little bit of information the results came down exactly where you would think they would in terms of right-left, pro-business, anti-business, pro-technology, anti-technology lines. And it led the study’s authors to realize that even nanotechnology could create a culture war, it could be a wedge issue, and that, weirdly, once people had two paragraphs of information on the subject, they felt incredibly confident in their opinion. In fact, they felt as confident in their opinion about nanotechnology as they did about any other political opinion that they held. And it struck me as I read about this study that all of us now, with our phones, the Internet, we are all two paragraphs of information away, we are seconds away from two paragraphs of information about any subject in the world. As such, we tend to feel really confident in our opinions about those things. And I know I did, in roughly 2004—I thought I had the answers, and then the work of the last ten years has shown me, at any given point of my life, if I look back about five years, I realize I’ve been a moron. And so I guess a lot of what goes for sanctimony in the novel is overconfidence in one’s opinion. That could be because of technology, that could be because of patriotism—the truth, it’s probably a [mix] of those things.

John Irving: We’ve certainly seen a lot of overconfidence lately. You know in any good novel there are more good titles than the one you get to use. That’s just true. But there are a ridiculous number of good titles you could have used. Phrases that you do use.

Nathan Hill: I needed you like a year ago.

John Irving: No, I think you chose the right one. I don’t think you can beat The Nix, but there are many other temptations. Ghosts of the Old Country. The House Spirit. And how about this one, your title for part three: Enemy Obstacle Puzzle Trap. This novel is all of those things. I like this one too: The Price of Hope, and this one: Every Memory is Really a Scar. That applies to this novel very well. And what we were just talking about, Sanctimony in America would work. It would work. You must have had another title or two or three.

Nathan Hill: Yeah, you just mentioned three of them. Enemy Obstacle Puzzle Trap was a possibility. The House Spirit was a possibility. What was the fist one you mentioned?

John Irving: Ghosts of the Old Country.

Nathan Hill: Ghosts of the Old Country was a possibility. My agent said no, we can’t use that title, it sounds too Cormac McCarthy. It’s like, you’re right.

John Irving: Really?

Nathan Hill: The title of the book for the entire time I was working on it came from the first line I wrote. I had just seen this parade in 2004 at the protest at the 2004 Republican convention. I had seen a parade where people walked from central part to Madison Square Garden with empty coffins with American flags draped over them to symbolize our Iraq War dead. And I thought it was not only a really moving moment but a gripping image, and so the first thing I wrote was, “There’s a body for each of us.” I was imagining a character holding the coffin, there’s a body for each of us. And A Body for Each of Us was the name of the book for ten, twelve years until literally the day before we sent it out to publishers, when we decided it didn’t work any more, and so my agent and I were looking around for a new title and decided on The Nix.

John Irving: Did you see how casually he used for ten or twelve years? Most people, probably some of your friends among them, would have written two or three novels in the time it took Nathan to write this one.

Nathan Hill: And they did.

John Irving: Which probably galled you at the time a little.

Nathan Hill: A little bit—you know, you work.

John Irving: I'm an ending person. I care about them deeply, and what matters with an ending is that you, the reader, have the feeling that it’s where the novel was always going. Even if it wasn’t. It must have the inevitable feeling about it. When did that come, the ending you were driving to? Because from a reader’s perspective, it’s so much where this novel always was going. It’s hard to believe you didn't always know it.

Nathan Hill: I didn’t always know it. I'm so jealous of your process where you know where you’re going—you find the ending first and you write to it, is that right?

John Irving: That’s because I’m slow.

Nathan Hill: I didn’t know where I was going with this novel, and that last line came to me—if the novel took about ten years to write, that line came to me year seven. But for a long time I had a different ending in mind, [and] for even longer I had no ending in mind. I didn’t know what I was doing. When I first started, and I've said this before in other places so maybe you’ve heard it before, but when I first started writing this novel in 2004 I was just out of my MFA program and, looking back on it now, was very careerist. I wanted to write a certain kind of story that would get published in a certain tier of literary journal so that certain editors and agents would pay attention to me so I could put something on my CV and get the job I wanted etc., etc., etc. It was a widget for me to get what I wanted. And unsurprisingly the writing I did was very bad.

That went on for a couple of years until at some point, I had left New York, I had started teaching and I kind of threw myself into teaching because I wanted to be good at it and I liked it much more than Samuel does in the novel. I actually like teaching, but that makes for pretty bad drama, so I made Samuel pretty sour. And there’s this part of me that thought I missed my shot, you know. I’m not going to do it, this is it, I'm a failed writer. And that was the best thing that ever happened to me, feeling that way, because I stopped sending stuff out, I stopped worrying about editors and agents. The only person who knew anything about the novel was my wife. And I would read to her a few pages every couple of days, what I had done. And if it was going really well she would say, that’s really great. And if she didn’t like it she’d say, that’s really nice. She’s always supportive, but sometimes a little less so. But one of the things that I realized while writing the novel was that I couldn’t treat it like this thing that needed to get done in order to advance my career, because publishing a book is hard and there’s no guarantee that would happen and there’s no guarantee that anybody would even understand it once it left the house.

So I couldn’t pin all of my hopes on that—it would be shattering—and instead I started thinking about writing almost the way a lot of people think about gardening. Nobody keeps a garden because they want to get famous. Nobody thinks their garden is a failure if a lot of other people don’t see it. It’s just, you like to garden. So that’s what the book taught me. Writing the book taught me that there’s some kind of everyday joy and delight in going to it and doing it. And so if there’s any humour in the book it’s because one of the prerequisites for me was that it had to be joyful.

John Irving: There’s a lot of humour in it. It’s very, very funny, in a sick way.

Nathan Hill: My favourite kind. So yeah, it had to bring me some measure of joy. So that ending emerged from feeling like I learned what it meant to be an artist, or what it meant to be a writer, from writing the book. And what the book taught me was to let go of my preconceived notions of who I was meant to be and accept the reality of what was going on and be happy about it and find some kind of everyday delight in what I was doing. That might sound like a really cheesy, self-therapy kind of thing, but it was very profound for me. And so that’s when I discovered the ending—when I felt, finally, I no longer felt in competition with people I had gotten my MFA with, people who were publishing all kinds of books and I wasn’t. I didn’t feel the kind of humiliation that I hadn’t published yet. I stopped worrying about that. I was teaching, I was keeping my head down and just doing this hobby when I could that delighted me. And so the emotion in the ending, I hope, reflects that epiphany that I had.

John Irving: Well it also reflects a phrase that you used in talking about it, the "letting go" phrase, because quite honestly, several hundred pages into this novel, if I had to put it down and guess how this novel might end, how this mother-son dysfunction story might end, I was guessing that a double homicide would be pretty likely. I was saying, boy, this is really heading to a personal and political Armageddon. But without giving away the considerable surprise, which you managed to hide so well, there is a remarkable moment when Samue—who not only is angry but you're angry for him, you’re angry on his behalf—there’s a wonderful moment when he lets it go. When he realizes that it’s destructive. And that’s really astonishing—there is a breath of air of a kind you would least expect.