Five years ago, I stood at the foot of a parched mountain with my father a few hours before dawn, in Muzdalifah, Saudi Arabia.

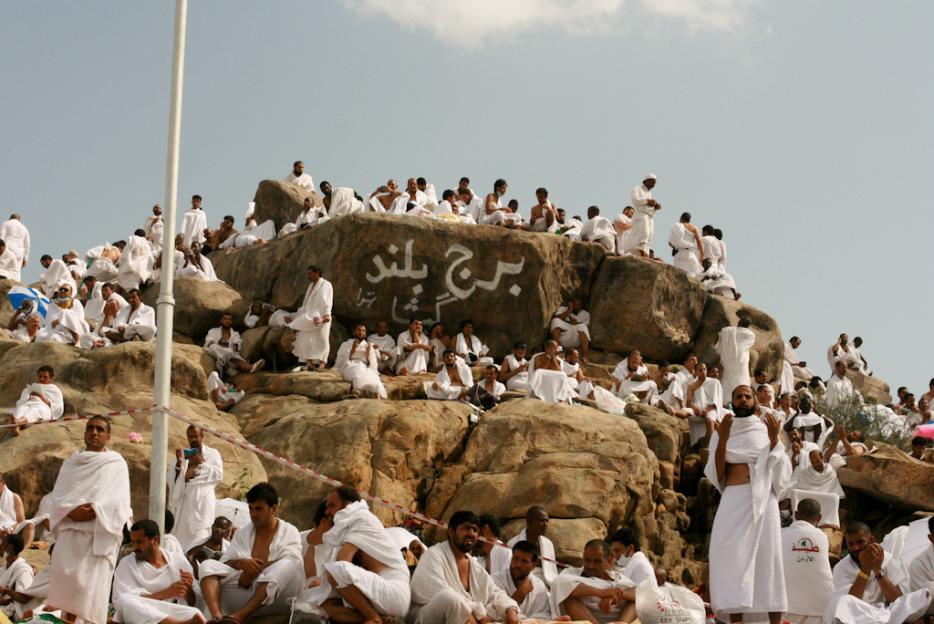

We were performing Hajj—Islamic pilgrimage—together with my mother. Under an endless sky and surrounded by millions of pilgrims, we were somehow still sheltered from the cacophony of mankind. My mother waited at the bottom of the mountain while my father and I began climbing the jagged rocks in search of seventy pebbles for each of us. These pebbles were to be pelted at the three walls in Jamarat, a reenactment of Abraham's pilgrimage—in Islamic theology, it is said that Abraham was guided by Gabriel to pelt Satan for the three times he tried to lead him astray.

The thing I remember about that night spent with pilgrims of the most gentle countenances, who spoke the universal language of laughter and tears, was climbing with my father and hearing him whisper "Allahu Akbar" as he blew the dirt off every pebble and filled his pouch. As the night blended into dawn, I bonded with papa among silent mountains, weeping men and countless stars. My mother watched from the bottom, rolling the beads of her tasbeeh, smiling when our eyes met.

Seventy pebbles sat in my pouch, seventy pebbles in his. We descended the mountain like gazelles, past the sharp ends of earth, and handed mama her share of the stones. Pilgrims began moving. I turned around to look at Muzdalifah for one last time. It is open ground surrounded by mountains, where the sky is our ceiling, the earth is our bed. And God is great.

*

When you enter “the meaning of Allahu Akbar” in Google, the first search results take you to Jihad Watch, Breitbart and Urban Dictionary. Jihad Watch tells you that Allahu Akbar is "the ubiquitous battle cry of Islamic jihadists as they commit mass murder." One of the definitions on Urban Dictionary, home to some of the internet’s most passive aggressive users, states Allahu Akbar is "what is said by people beheading hogtied victims 'in the name of God.'" And Breitbart, the ominous prophet of doom and gloom for the average conservative, insists that Allahu Akbar means "Allah is greater than your God or Government."

Takbir—that is, Allahu Akbar—is a strange thing. It is Arabic for “God is great.” But to the westerner who consumes the world through purposefully tailored headlines, deliberate SEO and sequential images meant to invoke fear, takbir is a terrifying thing. To the westerner, it’s something ISIS members scream before bloodshed and al Qaeda members chant before deploying an IED. It’s that scary announcement from the brown man with a beard that hides his mouth, obscuring his face, making it impossible for you to trust him. It’s code for “we’re implementing sharia here,” according to astute Republicans who can’t pronounce Iran or Iraq without butchering it (figuratively and literally) but are adamant on presenting a singular, restricted and unimaginative interpretation of an expression millions of Muslims use in millions of ways.

But to the average Muslim, takbir generously lends itself to numerous occasions and emotions.

Consciously, I heard takbir for the first time when I was four, maybe five, in northern Virginia when my mother prayed in front of me. I watched her kiss the earth with all the love in her being. Before she knelt in prostration, she whispered something. She came up once more, whispered it again, then gently knelt in humility. Her forehead touched the ground, the tip of her nose softly grazing the prayer rug, her eyes closed in unwavering thought. To a child, this graceful movement was spellbinding. I strained my ear to hear her again. “Allahu Akbar.”

But takbir is introduced to us before we can even attach meaning to spoken word. When we are born, the azaan—call to prayer—is performed to us at a pitch softer than cotton. The day I was born, I had already been introduced to this expression that would later on become my refuge in times of despair, my cry in times of joy and yes, my roar in moments of indignation. My father softly recited "Allahu Akbar" in my ear when I came into this world.

Born after eight miscarriages, I was my parents’ miracle.

*

When words wound, to borrow critical race theorist Richard Delgado's phrase, the first injury is confusion. How do we understand the link between the word and the wound? Is it the physical manifestation of intention that injures us? Or is it the historical context and origin—the discursive nature—of a word that lacerates our sense of belonging in this world? What if the language used was our own language appropriated against us?

I never asked myself these questions when a white man jeered "Allahu Akbar" at me on Fifth Avenue. He gestured a bomb exploding over his head and then went on his way. Questions rooted in theory abandon you when the banality of violence takes you as its hostage. I never asked myself these questions when alt-right Twitter users spread misinformation about the Quebec mosque shooting—initially, Fox News reported that the suspect was a Muslim of Moroccan origin who shouted "Allahu Akbar." When authorities confirmed the suspect was a white French Canadian with a predilection for Marine Le Pen and Donald Trump, the neo-fascist Twitter-sphere made no attempt to amend the error, despite Fox issuing a correction at the request of the Canadian government.

I had to ask myself: When Alexandre Bissonnette entered the Centre Culturel Islamique de Quebec that night, did he yell "Allahu Akbar" to mock the worshippers before killing them?

*

There are instances of takbir you haven’t heard of.

For miracles and in chaos. When Pakistan was hit by one of the most devastating earthquakes in its history in 2005—with over 87,000 killed—I still remember the streets filled with takbir as apartment complexes, schools, plazas fell to the ground. Reshma Begum was trapped under the rubble of the 2013 Savar building collapse in Bangladesh. She was found alive after seventeen days. As rescuers pulled her out of the mouth of destruction, crowds cried "Allahu Akbar" with joy and gratitude.

For the quotidian. My grandmother yawns "Allahu Akbar" when she stretches in the morning or when she removes something harmful, like a shard of glass, from the street so no one gets hurt. In an exceptionally brutal game of rugby in Prospect Park, Brooklyn, my friends and I shouted "Allahu Akbar" with triumph after scoring against our opponents. Imagine the terror on the faces of those around us.

For beauty in the overlooked. While sauntering through the woods during her daily walks in Virginia, my mother recorded a video of a deer with her youngling. They seemed calm looking at mama and continued enjoying the verdant surroundings. A few seconds into the video, you can hear my mother whisper "Allahu Akbar" with love.

For laughter, too. When my father thinks he looks great in his three-piece suit with a dash of discounted Kouros on, he grins in the mirror and says "Allahu Akbar" to himself, popping his collar. Indeed, God is great, for God made it possible for papa to own an Yves Saint Laurent fragrance for $54.49.

And in despair. Takbir can be used to express awe at something of such magnitude that it shakes the core of your being. I know so many friends who softly cry "Allahu Akbar" into the warmth of their palms when life becomes unbearable and loneliness, unending.

The meaning of takbir expands itself to a dizzying number of sights, sounds, tastes and sensations. Two Arabic words encompassing a spectrum of emotions in one simple sentence.

*

Charles R. Lawrence III describes racist speech as a "verbal assault," highlighting the “instantaneous” injury of racial invective. I wonder what he would say about racist speech that snatches something beautiful belonging to you, violates it before your eyes and throws it back at you, mangled and orphaned.

I try not to think about takbir in the mouths of men and women who can’t see beyond tropes. I try not to think of it in predominantly English newspapers that suffer ahistorical analysis but also a dearth of linguistic diversity. I try not to think of anti-Muslim animus when I think of takbir. Above all, these days, I try not to think of Bissonnette possibly yelling "Allahu Akbar" before opening fire on dozens of Muslims mid-prayer.

Isn’t it strange how two words have been mercilessly mangled in society’s comprehension simply because someone was too paralyzed with fear to understand their meaning and usage? Isn’t it also fascinating how two words can summon the breathtaking extent of human emotions?

When I think of takbir, I think of that night with my parents in Muzdalifah five years ago. They brought me for Hajj to thank God for giving them a daughter after eight shattering losses. Eight heartbreaking attempts. I think of my mother handing bottles of fresh water to pilgrims as they marched on. I think of her warm face, her tired eyes. And I think of my father gently crushing dried mud between his index and thumb, handing me the smoothest of pebbles and praying under the blanket of a benevolent sky.