A few years ago, a friend went to visit her eldest sister in Australia and sent me a photo of the two of them, matching smiles, matching blonde hair, and matching blazers. Her sister had taken her shopping, and insisted they both buy the tailored, textured piece. “It looks great on you!” the sister said.

“It makes me feel like a fraud,” my friend told me later, back in Montreal drinking horchata on St. Denis.

I started thinking about blazers, and what they represent: a piece of clothing which, whether due to uniform history or modern associations, you somehow feel you have to earn your way into. I started asking women I knew how they felt about blazers, and the responses were fascinating—my mum remembered the headmistress who democratized the sixth form at her boarding school by doing away with different coloured blazers for prefects, some friends talked about blazers like they were armor and others described avoiding them like disappointed relatives. People talked about gender, and tailoring, and design, and body size.

A slate of recent television shows have been using women's workwear in general—and the blazer in particular—as a narrative tool. One of the most notable of these, The Good Wife, ends its run May 8. It seemed like a good time to gather a bunch of smart women together to deconstruct blazers.

Haley Cullingham: Why doesn’t everyone introduce themselves by sharing a favourite iconic blazer?

Natasha MH: Lately, I’ve been on a huge Princess Diana binge, so I have to say that a lot of the blazers she wore post divorce are ones that I enjoy. Even though she’s wearing brands like Escada, Armani, etc. there’s something in the way that she wears them—very casually, almost a bit defensively (or offensively? I’m not sure yet) that makes me feel that if she weren’t from the aristocracy (hell, even if she was, but she didn’t marry Charles) she would totally feel at home—sartorially speaking, that is—fronting a new wave band or something.

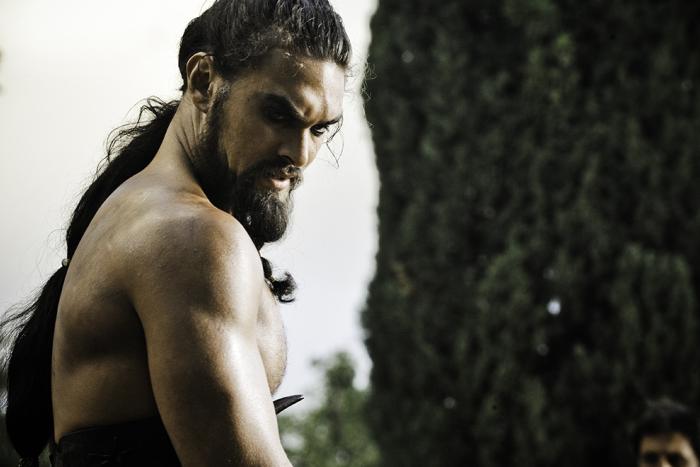

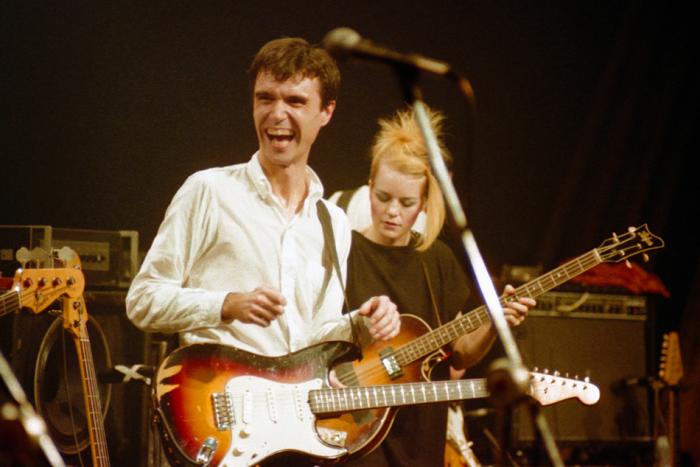

I tend to like blazers (and if I’m allowed to be a little lazy with classifications, suits as well) that wear like pajamas. So I’ve always had this weird love for Bryan Ferry/ David Bowie in the '80s when they’d wear these suits that felt like they had just rolled out of bed in them. Also, not quite a “blazer” technically, but we definitely see elements of tuxedo jackets (especially after YSL “Le Smoking) on quite a few blazers today, so I’m going to also have to go with Catherine Deneuve in “Le Smoking” as well. But also Mary Kate Olsen in that oversized pink blazer, and also Molly Ringwald’s navy blazer in Pretty in Pink. There’s something about a garment that is so “formal”/”professional”/”structured” that just screams belonging to an exclusive club of sorts, or a professional designation (we’re going to have to talk about class, professionalism, and workwear at some point), and wearing it like you would a pair of pyjamas, a shawl, or a sweatshirt .... I really like how bratty (insouciant, maybe?) it is. Like, I went to a school with uniforms, so I have this definite love-hate relationship with blazers, but when I love them is when they’re a little oversized, very loose, boxy, and paired with something that, to a pre-2000s eye, would be VERY unexpected. Rihanna’s someone who I think has AMAZING blazer game. The other blazers that I’ve become fascinated by (especially as I was prepping for this roundtable) were the blazers that female celebrities (think Lindsay, Courtney, WINONA RYDER) wear when they’re in court. There’s something fascinating about how these three interpret “professional” attire, especially when you compare/contrast it against their respective public images.

Ziya Jones: Not to become a terrible parody of myself, but Jennifer Beals’s character in The L Word, Bette, wore the most aspirational blazers. There was something about watching a woman excel at work (but also sometimes cry) in a neutral-coloured power suit that really did it for me.

I’ll go ahead and pigeonhole myself further: there’s also Gladys Bentley, an openly gay, black musician who was big in the Harlem music scene in the 1920s and ’30s. She played piano and had a rad as hell growly voice. Her signature look was this white tuxedo. (And, okay, that’s more of a jacket than a blazer, but it still makes me want to weep.)

Haley Mlotek: The first blazers that came to mind were: Shania Twain in the “Man I Feel Like A Woman” video, Annie Lennox in the “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)” video, Sharon Stone’s white (sort of Le Smoking-ish, hi Natasha) jacket in Basic Instinct, and Fran Lebowitz’s forever-uniform of blazers, jeans, sneakers, white button down shirt. OH, and Debbie Harry is, I think, an underappreciated blazer icon; her leather jackets were almost always shaped like blazers, with the lapels and the tailored sleeves, and there’s one photo of her with a tan blazer draped over her shoulders that I love, and one concert photo of her wearing very short shorts and a t-shirt and tights with a blazer over it that is extremely important to me. I think a few of these are technically jackets but I don’t care. I can identify some of the patterns that I love pretty quickly: I love good tailoring, and I love a sleeve that gets progressively tighter down the arm, maybe a little cropped so that it hits right above the wrist. I love a really tight dress or shirt or short skirt with a long blazer over it. Mostly I’m into traditional blazers, but there’s something about the way Sharon Stone slips off that white jacket so easily that endears me to the whole Le Smoking/tuxedo jacket/oversized lapels silhouette. I think it’s too simple to say that I like the masculine/feminine thing when it comes to blazers, even though that’s clearly a part of my pattern; it’s more, like, the idea of a fitted layer that slips on and off like nothing, but makes everything under it look so different.

Scaachi Koul: No blazer has been so important to me as Tina Fey’s dumb blazers in a near-decade of 30 Rock. I don’t know why, maybe it was reassuring as a weird and excessively formal high schooler (a trend I’ve continued as an actual adult, which somehow makes this worse) to see someone wear blazers, constantly, as a vague attempt to look put-together even when your life is burning down. This has very little to do with actual fashion or even how a blazer makes me feel (overheated, usually) but I liked the idea of Liz Lemon, harried and stressed, putting on a blazer to get something done because grown ups wore blazers. Being 14 is hard and bad, but hey, if this white lady can pull it together by putting on “a woman’s blazer from a very expensive blazer shop called Rico’s,” maybe there is hope for me yet.

Kiva Reardon: Blazers have a weird relationship to respectability for me. Like, the way as a teen you thought that white eyeliner was chic and that crimping your hair was elegant. Which isn’t to disrespect a blazer, but this is why I love Kim Kardashian’s use of them. In all honesty, when she JUST wears a blazer, it feels like such a beautiful form of subversion against this item that’s coded as business. I also just bought a very non-work appropriate dress (it’s more two strips of fabric that cover my chest and some more material that barely keeps my bum under wraps) and when I asked my friend if it was ok to wear to an event, she replied instantly, “Just wear a blazer!” Blazers are like some bulletproof shit against any kind of slut shaming.

I feel like the best example of this “blazers mean business” idea is Kerry Washington as Olivia Pope in Scandal. That show, which deals with sexism in so many interesting ways, also uses Olivia’s wardrobe to demonstrate the limits of what women can wear at the office. In one episode, Olivia has to give a woman a make-over to make her media friendly after she’s been accused of having an affair with the president (spoiler) and, naturally, blazers start coming out of the closets in droves. But saying all this, I’m not sure what it says about me that I don’t even own a blazer…

Haley Mlotek: I’m just going to address the exceptionally well-dressed elephant in the room and say that the only reason I didn’t mention Alicia Florrick is because that CLEARLY goes without saying. She is the best thing to happen to blazers since, like...blazers.

Haley Cullingham: Haley, Instagram tells me that we own the same blazer and both bought it because it made us feel like Alicia Florrick.

Haley Mlotek: THE WHITE BLAZER WITH THE BLACK PIPING?!?!

Haley Cullingham: YUP. All of you have mentioned the somewhat-charged nature of blazers. For whatever reason, they feel like items of clothing that symbolize something. Is that true of all clothes in the same way it is of blazers? I feel like it isn’t.

Haley Mlotek: Oh no. All clothing symbolizes something. That’s a very sweeping answer to a very specific question but I do think we could talk about, like, culottes, or socks, or sweaters in exactly this way. Clothing is given charges by usage, in my humble opinion. So for me the question is always: what charge have we given to blazers, and why?

Natasha MH: I think that all clothing DOES symbolize something, especially when you take the outfit all together. When Simmel talks about fashion, he argues that it can refer to a kind of cohesiveness and belonging, as well as closing off the group to those deemed of inferior rank. One of the reasons I’m attracted to clothes, fashion, and fashion theory is because I like to think about clothing as something aphoristic. There’s a point at which aphorisms can seem really, really obvious, and you can take them at face value, but if you’re able to read under them, or get into the mindset of the writer/the culture that they were writing in/their references, the more aphorisms can seem like love letters hidden in plain sight. Some of the best writing can come from writing for the people that will understand you (or, like, have yet to understand you), I think all dressing is the same way too. The introduction to Fear and Clothing (yes, I came vaguely prepared with index cards) talks about style being “the collision point between our fantasies of who we are, the larger realities we live with, and the way we are perceived by others.” When you consider the relationship that women have in particular to garments like blazers, jackets, and suits, as they become members of the professional class, you see the confluence of so many things. The need to succeed, to be taken seriously, to emphasize (or de-emphasize, perhaps) gender/sexuality/class/race (race and “professional” dressing is a particularly loaded thing to discuss). I started looking a lot at women who worked in finance, in law, in academia—fairly conservative (I know that people may fight me on the academia point, but it’s a lot more conservative than it looks, from my vague fly-on-the-wall, observing other people do it sense of things) professions in which you don’t have as much a say in how you can present yourself.

On Wall Street, women presenting themselves as members of a financial elite (this was during the '70s and part of the '80s, and of course, there are always outliers who eschew convention completely, and it sometimes really works out for them) wore navy blue suits and ties. By the 1990s, you had the “power suit”—so, different colours, cuts, and fabrics, but always “done” hair, no longer than shoulder length, and these women definitely wanted to distinguish themselves from other women (namely secretaries, and anyone working in the back office, poorer women, who still, coincidentally were working women) in the office. And they really took it upon themselves to discipline themselves and others. Melissa Fisher did some ethnographic research on women in finance in the book Wall Street Women, and she spoke to the pressures regarding dress, appearance, and behaviour. And I think that we definitely see that same pressure in the kind of advice offered to women in stuff like Dress for Success, Lean In, and godknowswhatelse in terms of self help.

Anyways! Blazers, in particular, I feel have an air of exclusivity to them, because they evolved out of upper class leisure sports, cricket clubs/rowing teams if my memory serves? But before that REALLY took off, they were associated with the British navy. So, in their own way, they were kind of athleisure before athleisure was a thing. Or at the very least, one version of the flak jacket as worn by civilians. The blazer was a sign of belonging to a particular club, or team, and then when you get into discussions of private school uniforms, universities, etc. blazers were a way of stating that you belonged to a particular group, and you could see that through the colour/ the crest.

Kiva Reardon: For real, I’m now just googling Kim K in blazers and getting lost in the magic.

Ziya Jones: I did the same with Princess Di blazers 10 minutes ago. Like, come. On.

Natasha MH: I LIVE for Princess Di in that Escada outfit. It’s a very traditional mens’ style blazer (is it navy, or black, I can’t tell?) with the gold buttons.

Scaachi Koul: I’ve been thinking a lot about how men’s blazers have these superior qualities that no one has gotten around to providing to women. Like why do men get all these hidden compartments inside the blazer that I do not get? Iwant to reach inside my boob area and pull out my phone or a little notebook or a cigarette or someone’s else’s finger. Why is that so hard? Why can’t I have what I want?

Natasha MH: Oh man, men’s blazers do have those hidden compartments. I mean, it is possible to find in some women’s wear, but only if the blazers/jackets are tailored like men’s clothes. So sometimes, I just tend to just buy boy’s blazers (like blazers made for little boys/ tiny men are my godsend), or just do the oversized man’s blazer.

Haley Mlotek: This is SO REAL and I actually KNOW the answer and it is going to INFURIATE you.

Scaachi Koul: Balls, but tell me.

Haley Mlotek: It’s because conventionally tailors believe women don’t want the added “bulk” of pockets. Like, pockets will make our tits or hips look too bad, and God forbid that happens.

Scaachi Koul: Sure, and this is also true of jeans which is why I REFUSE TO WEAR PANTS but I wish just one company would get around to leaving me little compartments. My cans are formidable, they will come through even with the added bulk. That is what would truly make me powerful.

Haley Mlotek: Triple Five Soul used to sew drug pockets in all their clothes, no matter the gender. But I think that’s different.

The image of you reaching into your side pocket and pulling out a pack of cigarettes is extremely stirring to me.

Scaachi Koul: Who wants to fuck.

Haley Mlotek: Let me just slip off this blazer.

Kiva Reardon: Who has ever had sex in a blazer? This seems like a very good porno concept.

Natasha MH: I have never had sex in a blazer, but if I need to run to do something and don’t want to put on too many clothes, I am a fan of just throwing the blazer on, and wearing it as a dress.

Kiva Reardon: Yes. Case and point, this.

Scaachi Koul: I think that’s literally what all those Sarah Palin porn parodies were about. Blazer boners, little else.

Kiva Reardon: Yo, tho—Palin!! This is important to talk about re: blazers. Similarly Hillary “neoliberal” Clinton. The blazer in politics is basically all that women can wear. Think of Condoleezza Rice. But here’s my REAL pressing question: what’s the difference between a blazer and jacket?? Blazers to me feel like a separate piece that goes on top of an outfit whereas a jacket is more integrated? Like part of a suit?

Natasha MH: I’ll try to keep it brief. Blazers: They’re usually a solid colour, have silver or gold buttons, and they aren’t as sharply tailored as a suit jacket. They just exist without bottoms. Blazers tend to be “softer” in terms of their fabric (think flannels, cashmere, worsted wool).

Scaachi Koul: Remember that little red number Sarah Palin had? That was a good blazer, it was a shame about her mouth. And the words. The words that struggled out of it.

Haley Mlotek: I think a jacket is for warmth, a blazer is for sex. Or politics. Or both.

Kiva Reardon: This explains Kim in a blazer being everything to me.

Natasha MH: I feel like this a good time to start humming Cake’s “Short Skirt, Long Jacket” all by my lonesome, since we’re talking about competence, clothing, and well, sex. There’s just something to that combination that just … works, and while I see it as a style/ playing with proportions kind of thing … it’s clear that people tend to take it a lot more sexually.

Haley Mlotek: Ziya, I want to know more about those neutral power suits—was there something about the colour that made it particularly powerful?

Ziya Jones: I think so, in a way. Especially in the ‘80s/’90s, a lot of women’s office wear was, like, bright orange? Or purple? If you were a teenager, like me, who was trying to move away from dressing in a more typically feminine way, a hot-pink power suit seemed like a nightmare. But grey slacks and a blazer? Yeah, ok. I could do that.

Haley Mlotek: And do you wear those kinds of outfits now?

Ziya Jones: Definitely. Today I’m wearing black pants, a turtleneck and a grey blazer (please destroy me). It becomes about aping what you want to be read as (which Scaachi alluded to further up)—for me: professional, calm, queer. Part of me hates that I’m still guided by some media messages I absorbed as a teen, but I think you were all right in saying it’s impossible to escape the meaning we give clothing.

Haley Mlotek: Ziya, that is so fascinating. Can I ask what you do for a job? Does that play into your idea of professionalism at all? And “professional, calm, queer,” seems like an especially important point to make in light of what we were saying earlier, blazers alluding to a kind of subdued but present sexuality.

Ziya Jones: I’m an editor at a magazine, and I work in an office where I’m the youngest person by far. So I don’t know...maybe it’s a compensation thing?

In terms of the queer factor, I think as soon as women put on anything that remotely resembles menswear their sexuality becomes more open to questioning. Remember when Kristen Stewart starting wearing plaid shirts and blazers? Everyone lost their minds. It’s annoying when you’re not doing it on purpose, but when you are, it’s kind of a convenient signifier.

Haley Mlotek: As soon as you started typing “Remember when Kristen Stewart” I was like *emphatically nodding head.*

I think I know what you mean by convenient signifier, and I want to hear more—like, is the point to use your blazer as a shortcut for a message you want to send?

Ziya Jones: Honestly, yeah. Especially at a party, for example, a blazer, paired with a plaid shirt and my 12-year-old boy haircut is a great way to say, “I date women and I also have a career.” Which is falling back on lots of stereotypes. But it really does eliminate some unwanted attention from people you don’t want to interact with and sometimes can bring you into contact with people you actually care to talk to.

Natasha MH: I think maybe if we’re talking colours, I would want to bring up the idea (you see this in people like Adolf Loos—see Ornament and Crime for what I’m talking about here, in Batchelor’s Chromophobia, and quite a lot of stuff if you’re reading about straight up colour theory) that the only acceptable colours (in Europe, so I guess by extension North America) if you wanted to designate yourself as “mature”, “intellectual”, “civilized”, etc. were black, gray, white, some blues, and mayyyyyyyyybe a brown or two. I think if we’re talking “neutral” colours (so like muted stuff like khaki, brown, tan, sand, etc.) … we’ve relaxed our stance on them as “professional” colours (there was a time where wearing a beige, or tan suit to work was like … verboten. Even fairly recently, when Obama showed up in a lighter coloured suit, people seemed to take a bit of umbrage to that)—but there’s definitely a correlation between the perception of certain colours, their perceived intellectual weight (well, as far as the West is concerned), and one’s social competence.

Kiva Reardon: Natasha, that’s so true. I know that as someone who has to occasionally stand in front of large groups of people for work, I almost never wear anything other than black. When I feel like I’m about to be super visible, I default to anything muted and that plays into some idea of intellectualism. (I also have a lot of imposter syndrome, and worry about looking “too young” and not being taken seriously; shoutout to internalized misogyny, much?) I don’t, for instance, own anything pink, coral, or in any shade of pastel. I had to be talked into buying a red dress, and when I do wear it I almost always have a black jacket over my shoulders. (I’m really starting to see why I should really buy a blazer…)

Natasha MH: It’s really interesting that you mentioned that, Kiva. If I think about some of the codes that women academics tend to abide by in terms of their own “professional” appearance, it’s a lot of black, a lot of grey. If you're in something like art history, design, or something, you can be stylish but not TOO stylish, lest people think you are unserious. Mostly on account of the “idea” that somehow you either have to do the eccentric tweed Oxfordian thing, or look like you got dressed in the dark or something. Although in the humanities, I think that there is a small group (think Valerie Steele) of people who really have fun with their outfits. I remember my friend telling me about how his mother (she’s a Beauvoir scholar) would encourage a lot of the women she was working with TO embrace colour and pattern.

There’s still a weird thing where if you exhibit even the slightest trace of femininity (or like, even polish) that somehow you’re not as good as your male colleagues. Which, I mean, if you’re staring at things to draw out their most fascinating details … wouldn’t that eye extend to, like, what you wear? Oh well. More dandyism for me then.

I wear a lot of black, mostly because I am a goth who never quite recovered.

Kiva Reardon: I wore black to a wedding last summer and am still hearing comments about that “bold choice.”

Natasha MH: My mom’s Bajan, so we’ve gotten into screaming matches about wearing black to weddings. Apparently it’s bad luck to wear black to a wedding because … it’s a funeral colour, or something.

Ziya Jones: How often does everyone here actually wear a blazer? I think I wear one 75% of the year. I’ll wear one to a party even if I know everyone else is going to be wearing band t-shirts and eating Doritos (I live in Montreal, it’s unavoidable).

Kiva Reardon: Fuck, I don’t even know why I’m here since I don’t own a blazer. I just wear a leather jacket over most things and am like, “Done!” I’ll leave now.

Haley Mlotek: I used to be really into buying blazers at Value Village, especially private school uniforms, because the sleeves fit so well. But lately I’ve been more into leather jackets and coats. I want to start wearing blazers again, if that counts. Fran Lebowitz’s look is really speaking to me these days. There’s something very daytime-drinks-in-the-city about a navy blazer over denim and sneakers.

Natasha MH: I always wear blazers. I think a lot of it is a holdover from going to all girls’ school, and blazers being part of our “number one dress”—which essentially was our most formal iteration of the uniform. I was always really, really skinny, and my parents would always buy my uniform one size bigger than it realistically needed to be, so I was always drowning in my clothes, which eventually became one of my signatures for dress. I remember HATING wearing the blazers in that context because rather than feeling “powerful” (I mean, how powerful can you realistically feel when you’re like, eight, and people are telling you what to wear?) I felt constrained by this pre-professional costume. Ditto mandatory oxford brogues, and button up shirts. I hated, hated, hated them. Loathed them. However, and this one of the many weird paradoxes of my life, as soon as I started buying my own clothes/stealing my mother’s blazers from the ‘80s to wear on days where I didn’t have to wear a uniform, I just started wearing these baggy, oversized blazers, suit jackets, and coats, and really loving it. Part of it was that I was really into androgynous (read: masculine tailoring/plays on traditionally “masculine” dress) looks a la Janelle Monae, Agyness Deyn, Tina Chow (in certain moments), Marlene Dietrich. Like, I never really considered the sexuality of dress until university, because I went to an all girls school and I am straight, and for the most part uniforms were this way of trying to take out as many visual markers of social difference as reasonably possible. There weren’t any dudes (I mean, we had male teachers, and sometimes we got the occasional cranky reminder to not change in the hallways) so a lot of my experimentation with style came from wanting to hide being terrifyingly thin … because, like, wearing fitted things looked AWFUL on me. The oversized blazer was one way of doing that. I liked the tailoring of a good boxy blazer, and the fact that they just hung a lot better than if I had tried to wear something that was a little more “body conscious” … because it would look a little absurd on me if there WASN’T something baggy, or that my clothes didn’t manage to take up the space that I physically cannot.

Haley Cullingham: For me, my (fake) leather jacket and my blazers serve the same function, which Ziya and Haley were talking about above, a shortcut statement, in different contexts. Getting back to this idea of colour, there was an interview in Vulture with Scandal’s costume designer, about how Olivia Pope started wearing colour on the most recent season, and how significant this was. And Alicia Florrick’s costumes in The Good Wife have always been so indicative of where she is emotionally, as opposed to characters like Diane Lockhart or Cookie Lyon from Empire, whose wardrobes seem eternal in their conviction and sense of self. If blazers are a narrative tool, they can be employed in different ways, and I wonder where that comes from.

Natasha MH: The blazers as a narrative tool is definitely a cool thing to point out. Mostly because I can think of at least two episodes of The Simpsons where a blazer is a MAJOR plot point for Marge’s class ambitions (the Chanel suit), as well as her professional (which, I guess, comes back to class—the Chanel suit was more about fitting in with a very specific kind of well-heeled woman) ambitions. The episode in which she ends up becoming a real estate agent, and that moment where she puts the red blazer on, she starts spinning around, ecstatic that she belongs to something larger than herself/she has a job—then camera pans out and you see that she’s still in this dull office setting. So there’s this weird moment there where her career hoop dreams become a drug for her. Marge’s desire to succeed vs. her moral scruples is the main crux of the episode … but working to DESERVE that blazer, that’s something that interests me.

Scaachi Koul: I’m not sure if this has been brought up yet, but a big reason I started wearing blazers was because initially, it helped dull or mute any sexuality I might have been exuding when I was younger. If you wear something short, or tight, or revealing, you can throw on a blazer and it balances everything out. This, frankly, was something I did far more frequently when I was younger and I felt like certain parts of my body were made of sin and needed to be hidden. Too much arm or leg was scandalous, so a looser fit blazer would counteract that. Anything with a low top could be neutralized by a dark jacket with a collar. I hate that I did this because how is that fair? But maybe a blazer is more of a security blanket when you’re not sure what your body is supposed to be or how it’s supposed to look, particularly when you’re younger. I remember I had some industry event even a few years ago and I had this dress that I just loved, but I refused to take my blazer off because my arms, my shoulders, my chest were exposed and I wasn’t sure if that was “appropriate.” So at least, if I’m feeling insecure and I put on a blazer, it can be performative and attractive while still hiding whatever I’m having a hard time with exposing. I’m not sure if that’s still true—I’m older and less interested in feeling bad about my collarbone—but we’ll see what happens this summer. I hope I’m braver, but, I still like the odd blazer.

Haley Mlotek: I think it’s so interesting that we’ve all mentioned wearing or liking blazers on completely different sides of a spectrum: as a way to hide the body or a way to totally show it off, or to like, perform two totally opposite identities (respectable vs. super ~sensual~).

Haley Cullingham: I wanted to ask if anyone has more thoughts on the subversive-blazer idea. I feel like Kim K. and Rihanna both wear blazers in really artful ways.

Kiva Reardon: Like I mentioned before, their (or at least KK’s) use of the blazer resonates as it makes something that’s supposed to be muted sexy. When I was living in Qatar, I wore the same blazer all the time—this tan linen thing—because it covered me up. When I moved back, I got rid of it because it was associated so strongly to me with hiding. The idea of taking a blazer and making it about boobs first seems, to me, a very un-boobed and non-blazer owning person, super interesting, even empowering.

Scaachi Koul: Okay, but seriously, you guys ready to fuck or what.