“Everyone has felt (at least in fantasy) the erotic glamor of physical cruelty and erotic lure in things that are vile and repulsive.” – Susan Sontag

I fell in lust with Tampa by Alissa Nutting because Amazon uses great algorithms to generate its lists of “You might also like.”

The domino effect began with my reading Maidenhead by Tamara Faith Berger (great, read it), which in turn led to Charlotte Roche’s Wetlands (gross, great, read it), which brought up the hilarious and brilliant How to Train Your Virgin.

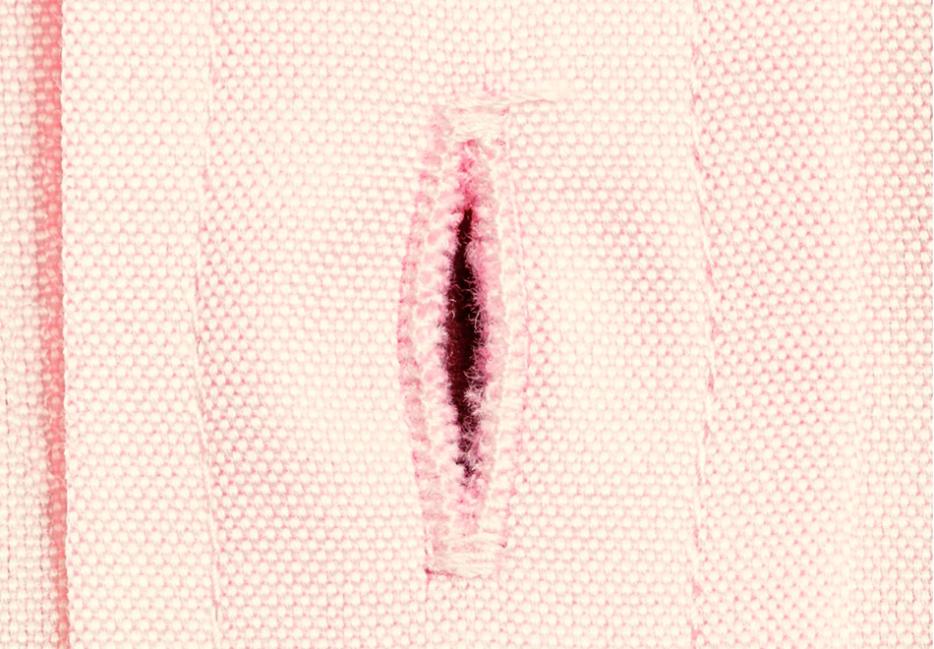

Finally, there was Tampa, its cover a close-up image of what first appeared to be a cunt hole (what else can I say? Writing about sex is hard. Vagina describes the inside; vulva, though preferred by those wishing to be appropriate, refers to the chops; and this was neither), but upon closer examination turned out to be the open buttonhole of a pink chambray shirt.

Trusting the robots, I downloaded my free sample and minutes later paid for the whole thing because the opening pages were dazzling. The entire book turned out to be dazzling. I laughed, my cunt hole throbbed (sorry), I forced my best friend to read the passages aloud over drinks without any forewarning about what they entailed because I wanted to make gin and tonic explode out of her nose (success!), and at home I forced my husband to listen to me read entire pages (which was hard for him because he’s a comedy writer, so when I laugh at other people’s writing it’s like watching me have sex with that person in our bed—presumably).

Here’s the gist:

In 1996, Mary Kay Letourneau, a very pretty 34-year-old teacher, raped her 12- year-old student Vili Fualaau, and now they’re married, and she still looks great. This is real life.

In 2013, Nutting released her erotic novel, Tampa, inspired by the crimes of Nutting’s real-life high school classmate, the very pretty predator Debra Lafave. In 2004, LaFave was found guilty of raping a 14-year-old. But she was deemed too pretty for prison. This is also real life. Tampa is not.

The novel is told from the point of view of Celeste, a middle school teacher who tries to seduce her students with varying degrees of success. Her outlook is so cynical, so refreshingly sharp and despicable. Her unlikability is exactly what made me like her.

To her great frustration, Celeste often has to satiate her desires via bizarre and inventive fantasies—imaginings that left me open-mouthed with sheer awe at Nutting’s ingenuity, and often breathless from giggling at the sardonic contours of Celeste’s dark mind.

Celeste on her husband Ford, who repulses her because he is an adult:

The thought of Ford dead didn’t necessarily arouse me. But the idea of pert adolescent males singing around his corpse, removing their colorful jerseys and swinging them above their heads in celebration, as though his death was a victory of sport and a crucial step to their winning a divisional high school championship—there was something greater than comfort in that image. It had the feel of Greek myth. I began to fantasize that the boys on television had been tadpoles who grew in Ford’s stomach until the day they were strong and large enough to rip their way out in a violent mass birth. It was almost enough to make me feel a hypothetical sympathy for Ford. If his body, torn in half, were indeed a spent cocoon that had incubated four lovely young men, I would kiss him on the cheek and mean it. Thank you, Ford. But there wouldn’t be time to linger. These new adolescents, sticky from their residence inside him, would need me to give them a shower shortly after arrival.

Nutting captures the way Celeste’s sexual fantasy becomes inextricably entwined with the idea of her husband’s death in such a weird and inventive way that I wanted to stand up on my bed and clap.

Later in the novel, Celeste is in her car, spying on her underage object of desire as he plays videogames. She is masturbating, and in order to come, she imagines the boy as a giant, unbuttoning his pants above the convertible where she is hiding.

“If horizon-colored pants began to bunch and fall and his teenage sex of skyscraper proportions was freed, I would drive my car into his toe so he would kneel down to investigate and accidentally kill me when the sequoia-sized head of his penis came crashing through my windshield.”

Celeste is hilarious, and in her sex scenes (which I have not included here, not because I'm trying to be polite—please, I said "chops"—but because I don't want to give them away) she is arousing. Yes, arousing: a problematic and self-incriminating but ultimately important admission. Vicarious titillation at these encounters implies that approval is somehow woven into our revulsion. Naively, I went online expecting to find more articulate confirmations of my admiration for Tampa. Instead, I found a slew of reviews slamming Nutting for writing about someone like Celeste. Historically, erotic writing is wedded to social critique and satire. But these reviews reflected an enduring puritanical tendency within American culture to dismiss women who write about sex. Consumer ratings were vitriolic (and misspelled, but whatever). When I mentioned them to a friend of mine, who is a novelist, he said, “Well aren’t they always?” He seemed casual about it, the subtext of his comment being that sites like Goodreads are for plebs.

But here’s the thing: Goodreads is important. Its members are taken seriously within the publishing industry. They receive free books. And given their rising status within the business, justified or not, we cannot dismiss them as simple consumers. They are modern critics. And they must be held accountable in turn.

*

Goodreads is a social cataloguing site that as of 2013 boasted 20 million users. It allows members to access an enormous database of books, annotations, and reviews.11It probably bears noting here that I have an admittedly muddled relationship with Goodreads. In order to look at the reviews of Nutting’s book, I had to borrow a friend’s account. The site banned me last fall after I wrote a personal essay for The Guardian about being a bad girl—not in the sexual sense, as was referenced here earlier, but in the sense that I am prone to bad behavior. Amazon purchased the site for a reported nine figures, but as of now little research exists to corroborate if activity on Goodreads leads to purchases on Amazon. Non-active users perusing Goodreads seem much more likely to use the site as one would use Wikipedia—that is, either to learn more about the context of a book they’ve already read, to qualify their opinion of that book, or to summarize for themselves a book they were already planning on not reading.

In the same way that Twitter users probably won’t show up to a protest because the simple act of having disseminated a social justice hashtag makes them feel productive, Goodreads members often “shelve” (that is, categorize within user-named categories) books they haven’t read and will not read. If “Did Not Read” or “Did Not Finish” shelves on Goodreads tell us anything, it’s that (as with TV recaps) consumers are happy to be informed about art via free recapitulations rather than via direct engagement. Reiterative opinions have become as gratifying as original ones.

One learns very young that fiction isn’t real—that actors on a sitcom, for instance, are not tiny elves inside the TV—and yet Nutting’s fiction is considered a memoir, one that, if liked or disliked, accordingly indicates a reader’s virginity or whoredom.

Goodreads members have become high-status players in the book world, though the precise relationship between ratings on sites like Goodreads and actual book sales remains murky. Book publicists make advanced copies available to “active Goodreads users,” whose audiences comprise mostly other active Goodreads users. Evidently part of the idea here is that guaranteed reactions, no matter who is reacting and with what kind of credibility or impact, are worthwhile.

As a platform, Goodreads enables knee-jerk responses that theoretically would not be considered relevant in more carefully considered, traditional, edited reviews. But democracy hinges on the linchpin of such knee-jerk response. Goodreads users have become powerful because their opinions, by sheer number, lend incredible insight into the ways that contemporary readers read. The site itself is a democracy. It is free and open to anyone.22Well, except me. The most revered reviewer’s thoughts are less valuable than the aggregated opinion of the masses.

As of today Tampa has more than 8,000 ratings on Goodreads, 1,753 of which are one- or two-star reviews. (Almost 30 percent of the book’s ratings on Amazon are one or two stars). Here are a couple Goodreads entries that I’ve found are representative of the majority of Tampa’s negative ratings.

Daily Billy [Goodreads]: The author is clearly encouraging this kind of behavior. This book was basically child porn with a weird fascination with shitting.33All usernames have been changed.

Donald [Goodreads]: Even more disturbing is this reader's gut feeling that [Nutting] has written her own fantasies. Like a previous reviewer, I was compelled to glance at the photo on the author's page each time Celeste alluded to her own appearance. While it seems the rule rather than the exception for today's crop of young female authors to cast themselves in their main roles, the context makes this instance more unsettling than most. Lock up your sons, indeed.

My issue with the views expressed is not that they conflict with my opinion of the book (whether we laugh or don’t is a matter of taste) but rather that in aggregate they echo the prevailing assumption that Celeste’s desires are Nutting’s. The majority include weird caveats like, “Now I’m no prude, but…”—implying that any opinion of the book naturally indicates something about the reader’s sexuality. In an anthropological sense this offers a disturbing view into modern literary discourse. One learns very young that fiction isn’t real—that actors on a sitcom, for instance, are not tiny elves inside the TV—and yet Nutting’s fiction is considered a memoir (perhaps women are incapable of creativity?), one that, if liked or disliked, accordingly indicates a reader’s virginity or whoredom.

Celeste is bad, so the book is bad, and the author who wrote it must be worse.

Lisa: … I'm not the kind of chick who judges a book by its icky content. I say bring on the sex, incest, murder; the more scandalous the better! But yet....This book just gives me the eebie jeebies. It's like as if the authoress were trying to be as vile as possible…for a totally sane rational woman to be writing the way she does?... letting us know that if you are bothered by this, you had best close this book before things get any more...creepy…

Here, “Lisa,” like so many other users, includes caveats about her own sexual openness before launching into a critique of the book. Her comments about Nutting’s mental health and her imperative that readers “best close the book if bothered” further underline the prevailing notion that by not shutting the book a reader somehow condones Celeste’s actions.

And then, she adds a little bit of ingrained sexism (it’s okay, Lisa, us ladies succumb to it constantly):

I'd like to say that not even men are so crude/disgusting in the private sex corners of their mind

And:

…knowing that it was a women writing the book I felt myself feeling almost disappointed with her! Sure, it's a tricky subject to tackle but she could've done it better. It felt to me that like she, in order to write about pedophilia had to try and and think/write like a man.

Reviews like Lisa’s are pervasive. There are thousands of defensive, disgusted, dismissive readers whose negative reactions to Tampa are couched in confusion and outrage at that confusion. The implications are upsetting. The prevailing notion is apparently that thought-provoking art vitiates its own worth.

Right-Thinking Woman: It made me feel uncomfortable and sick in a way I've never experienced from a book before.

The writing in this is beautiful. It is excellent.

The subject is not.

Thanks, but I really couldn't read this.

(I received a copy of this for free via NetGalley for review purposes)

Right-Thinking Woman echoes this idea that a book’s ability to make a reader feel bad cancels out its literary virtues. Many other users also admit to likingthe book, saying that they couldn’t put it down, that the writing is great, but that Celeste’s behavior made the book terrible.

Catarax: Before you think I gave this one star because I'm a "prude", I actually gave it one star because I simply did not like it. The writing itself was lyrical and I think Nutting has some talent, but this book to me was the equivalent of painting the Mona Lisa with excrement.

Celeste is bad, so the book is bad, and the author who wrote it must be worse.

*

Tampa’s consumer ratings reflect a prevailing sexism even among those who are, presumably, paid for their opinions of the book. “Professional critics” are no better than Right-Thinking Woman.

“You're gorgeous; you're young,” an interviewer from Cosmopolitan remarked to Nutting. “How much has your own experience of being a young, attractive female played into creating this book?”

And this, from a Tin House interview conducted with Nutting in the year 2013 (ah, 2013—a time when humans were so edgily throwing around the phrase “post-feminism”):

“Have you ever had a fixation on a certain age or type of person?”

Evidently Tin House, much like Donald, Lisa, or Daily Billy, could not comprehend how Nutting might be able to write fiction about pedophilia without actually being a pedophile. Or else the interviewer assumed that because she was “that kind of woman” who writes about sex, Nutting must also be the sort to discuss her sex life with strangers. This rankled me, because Humbert Humbert can rape Dolores Haze to eventual acclaim. But with Tampa, there seemed to be only one question—echoed again and again, implicit in every interview, every one-star rating, every critic’s self-servingly virtuous tone:

Was Nutting a good girl, or a bad girl?

“Have you ever had a fixation on a certain age or type of person?”

“I like men with beards,” Nutting responded gamely, clearly used to the bullshit by now. “There’s something kind of closer-to-nature for me about beards that’s pleasant. My husband has a really great beard and the other day at the park, a bunch of those white fuzzy dandelion seeds were blowing around in the air and got lodged in his beard.”

Perhaps while reading this you noticed the word “beard,” which Nutting repeats four times. You don’t have to be an English major to grasp the subtext: by reiterating her preference for “beards” she implicitly emphasizes her attraction to male humans of a certain age—not guys who are only slightly capable of growing facial hair (like those wispy, despondent, Vili Fualaau-style-circa-’96 mustaches), not adolescents, in other words, but fully bearded post-pubescent-hyper-masculine-lumber-jack-type men. Specifically, her husband. She is not a pedophile. She is monogamous. She is good.

When men write 100-plus pages of erotica, it’s a novel, but when women do, it’s smut that, with every (often brilliantly executed) sex scene, denigrates itself and the author, because the world is bullshit and sexist.

I called Nutting to ask, among other things, how it had felt to write a hilarious novel replete with smart social commentary, and almost exclusively face reactions about her presumed pedophilia.

“I think a lot of interviewers and readers really wanted to engage with this character and were hoping that they could do that through me,” she said. “At times it got a little frustrating … because at times it got a little hurtful … some of the accusations, where people really didn’t see any distinction whatsoever between this as a novel of fiction and a memoir, were pretty scary and upsetting for me.”

*

While talking on the phone with Nutting, I scrolled through some more of the one- and two-star reviews, hovering over one left by a user called David. “I am pretty sure the intent of this book was not to be funny,” he wrote, going on to complain that “a woman wrote this book and got it published where as a man would probably get arrested.”

I narrowed my eyes at the faceless David. A man would probably win awards. In general men who explore the grey areas surrounding consent and pleasure and perversion, men who write about fucking and murdering women—men who acknowledge women’s bodies as being public—these men are interesting writers. They write literature. I’m thinking specifically of Lolita, American Psycho. Of DH Lawrence, James Joyce, Ian McEwan, Henry Miller. When men write 100-plus pages of erotica, it’s a novel, but when women do, it’s smut that, with every (often brilliantly executed) sex scene, denigrates itself and the author, because the world is bullshit and sexist. Nobody asks Dick Wolf, the creator of Law and Order: SVU, whether his show goes into such gory detail regarding imagined rape (of children, women, men, animals) because he is a rapist. But when a woman navigates illegal sexual acts in her writing, someone needs to call the police.

Johnny: All writers write from experience, whether actual or from a deeply imagined preoccupation with the subject matter and, in the case of Tampa, no writer could describe the lusting after fourteen year old boys, as Ms Nutting does in great detail on almost every page, without having personal experience of being a hebephile.

To avoid screaming I shoved a chocolate bar in my mouth.

“The disturbing aspects of life. That’s male territory,” Nutting told me, “that’s for the male imagination. Male writers get to go to all the dark corners, right? Whereas female writers, they get the domestic or the emotional landscape and that ... that’s our territory. We can only write our own desire and what we want to happen to us or to our bodies.”

She admitted she’d been rattled by the reactions to her book, that it took her a while to recover from the slew of accusations that she was some kind of sexual deviant because she’d made up a world where one existed—but that she’d since reached “a place of gratitude for all of it.”

“How long did it take you to get to that place?”

“I’m at that place right now, but in like, five minutes?” She laughed. “It’s not always a stable place, but it did take a while. I’ll say maybe like half a year? Maybe six months out of publication.”

She explained that part of the personal tumult probably stemmed from the fact that Tampa was her first novel. She’d expected blowback, certainly. But what she encountered was not what she’d anticipated. It was much more personal.

“It still is, in some sense, a trauma,” she said, “and an assault because writing is such an isolated, solitary action in a lot of ways…I think a lot of writers certainly are very anxious obsessive, insecure people. I certainly am.”

I asked if she ever looked at Goodreads.

“Oh god ... I did at first,” she said. “And I had to stop … If you have these insecure, masochistic tendencies like I do … I just don’t ever feel like I can punish myself enough ever. Like ever. Like, I never feel like I can feel bad enough about myself. I think if that’s your nature, Goodreads is probably not the site for you … my therapist banned me and I conceded to her wisdom.”

*

So many of the reviews of Tampa dismissed it on the basis that it tried to “shock” readers. Thousands of users called it child pornography.

But isn’t all art attention-seeking? And ultimately, isn’t pornography versus erotica an issue of semantics? Etymologically speaking, pornography means “writing about prostitutes.” And so on that level, the label doesn’t fit here, at all. Gloria Steinem published an article in Ms. where she not only laid out the differences between erotica and pornography, but also discussed the right-wing implications of dismissing as filth those stories that explore women’s desires. And while Steinem would rightly accuse me of taking her discussion out of context, her argument regarding “that familiar division: wife or whore”—“good” woman … or “bad”—and how “both roles would be upset if we [women] were to control our sexuality” is applicable with Tampa, if only in a theoretical sense.

“The disturbing aspects of life. That’s male territory,” Nutting told me, “that’s for the male imagination. Male writers get to go to all the dark corners, right? Whereas female writers, they get the domestic or the emotional landscape and that ... that’s our territory. We can only write our own desire and what we want to happen to us or to our bodies.”

Throughout her essay, Steinem distinguishes pornography as being about an imbalance of power, but only on the condition that that power is used against women in particular. And so Celeste, though indisputably criminal, “bad” and more powerful than the boys she rapes, is also inarguably in control of her sexuality, making her a monstrous but feminist figure. She calls the shots, she subjugates males in violent ways that, beyond simply and intelligently speaking to societal double standards surrounding rape and victimhood, simultaneously reverse (and therefore disrupt) the typical model of masculine violence that we’ve grown accustomed to. So the vitriol directed at Nutting via her character, in this case, could be interpreted as a sexist rallying cry against the power and pleasure that Nutting has granted Celeste.

“As it is,” Steinem writes, “our bodies have too rarely been enough our own to develop erotica in our own lives, much less in art and literature.” Ultimately, she concludes that pornography depicts women pretending to enjoy themselves, whereas with erotica, the pleasure is real. And whatever one might think about Celeste as a criminal, she certainly enjoys herself. Thoroughly.

And even if we label Tampa as pornography, then to be consistent we must also dismiss Vladimir Nabokov, Ian McEwan, Philip Roth, James Joyce, DH Lawrence, and Henry Miller (among others), and if we do not dismiss these men as pornographers, then we must consider the sexism inherent in our semantic distinctions. Accusations of pornography are reinforced by what Susan Sontag called society’s “demonic vocabularies” used for describing the human need for art as a vehicle of pornographic imagination. But I would argue that those vocabularies now extend more to women than to men.

*

Such arbitration stems naturally from its inverse: self-judgment. Statistically, consumers of erotica and romance indulge on e-readers so that others can’t see what they’re reading. It is not uncommon for people to be humiliated by their own arousal. And Tampa produces morally ambiguous titillation that, if repressed out of mortification, drives self-unaware readers to project that self-loathing as moralistic judgment onto whatever or whomever “caused” it.

Ralph: One star probably isn't fair. It is not written badly. And really I skimmed it. Perhaps because every page brought some new embarrassment.

Tim: I kinda hate myself for compulsively reading it and so quickly, so there's that.

The self-consciousness that goes hand-in-hand with enjoying erotic material implies that the novels we read say something about us as people, perhaps that we are sexually carnivorous or perverted or secretly unsatisfied with the sex we are having. Arousal, revulsion, or arousal that is entwined with revulsion—these reactions are incredibly visceral, and if art can provoke strong reactions then it has obviously succeeded. Taste is irrelevant here. We don’t have to like something to acknowledge its success. But embarrassment and anger cloud judgment, causing people to lash out against the provocative.

It follows that part of the reason people are so generally uproarious about Tampa may be that it turned them on, and they didn’t want it to.

Getting excited by that which repulses actually doesn’t make us weird. In a study published the Journal of Abnormal Psychology, James Check and Neil Malamuth found that pleasure turns us on regardless of context—even with depictions of rape. “Portrayals that depicted the woman as experiencing sexual arousal, irrespective of whether they portrayed rape or consenting interactions, were reported … to be more sexually stimulating than those depicting disgust.” Although sex crime is manifest in almost every scene of Tampa, whether in terms of fantasy or action, both Celeste and her victims also experience ecstasy, and this shared pleasure, at least in the moment, overwhelms the violence that defines Celeste’s cravings and might otherwise categorize the book as pornographic. Yet instead of talking about how female pleasure mitigates the revulsion we might want ourselves to feel, men like David, Donald, Ralph, and Tim (and that guy who is Billy every day) demonize women for turning them on. It’s the old dichotomy of wife or whore. And what seems like a high percentage of readers take to the Internet, waving torches, talking about Nutting’s sick mind.

“Do you miss writing Tampa?” I asked Nutting. I told her I missed reading it.

She said that yeah, she had gotten to know the character well, and she missed the clarity of that familiarity. But Celeste’s cynicism was also a dangerous thing to get drawn into, Nutting continued, because Nutting had drawn that cynicism from within herself, which had forced her to explore an aspect of her own personality that she wasn’t necessarily proud of.

“Though I don’t share any of her sexual proclivities,” she hastened to add.

*

A creative writing teacher once told me that it doesn’t matter how evil our character is—if we give him one clear desire, we make him vulnerable, and vulnerability garners a reader’s sympathy. “Example: Begin with a thirsty-as-hell character,” he said, “and no matter how stupid or weird or monstrous he is, we’re going to read on until he gets that glass of water.”

While reading Tampa, I found myself reflecting on my former teacher’s advice, because when Celeste wanted to have sex with little boys, I wanted that for her too. It reminded me a little of John Irving’s novel The Hotel New Hampshire, in which a brother and sister are sexually attracted to each other, and Irving creates so much build-up between them that eventually I was cheering for incest. Their desires were not my desires. Celeste’s desires are not my desires. I have never raped a little boy or had sex with my brothers, nor do I want to, nor do I plan to. But why do I have to say that? Why is there this impetus to differentiate myself from the fiction I read? It’s not an uncommon defense mechanism. Getting turned on by a grown woman fucking a pubeless boy is a difficult thing to admit over dinner. But the only way to combat evil is to stop thinking of it in black and white terms, to dismiss the notion that it’s born and that good people can’t become bad, to shake off naiveté, in other words, and instead to viscerally grasp the insidiousness of what we see as vile: the shadowy magnetism of evil that makes people, perhaps all of us, complicit.

Erotica isn’t a flimsy paperback to read on, and discard into, the toilet. It’s a useless term that ghettoizes good writers and perpetuates deep-seated sexism that prevents women from getting the artistic recognition they deserve. In order to right wrongs and catch criminals and prevent crimes and educate potential victims, we need to talk, we need to discuss uncomfortable things. Humor sheds light on darkness. And by ignoring that fact, we’re shutting down the conversation. Sex writing is important. Arousing a reader with depictions of rape is important, because the only way to combat evil is to understand it, to feel some part of it ourselves.

“How many people have admitted to you that the book has turned them on?” I asked Nutting.

She laughed. “Well it’s funny, a lot! A lot. And the ways that people admit that are really different and interesting. Usually it’s like this almost whispered confession, Like, it’s something that is not the first thing that's brought up in conversation … [but] after a few drinks or something.”

I did some verbal nodding. We mused over how the shame involved probably stemmed from the same inclination to call Nutting a pervert. Leaps to judgment start with judgment of oneself.

“Every kind of reader is coming in with their own experiences and forming a projection and it is a fantasy,” she said. “That’s part of the trouble with the subject that the book wants to engage. That, often, we do fantasize about these older authority figures in our life. And that that’s encouraged and lauded when it’s young men thinking aboutit,and it is kind of seen as misguided or troubled or troubling or slutty, I think, when female students are thinking it, who are minors. That’s just a social judgment. Like, of course … boys are horny and that’s just fine!”

“Right,” I said, excited to riff. “Women are not supposed to find teenage boys attractive—and I know that the boys in your book are much younger than that, but there is something ... something sexist to not allow for the fantasy of male virginity because that is such a sensual and formative experience. Like, a bumbling boy who doesn’t know what he’s doing? There’s something sort of sexy about that. So I don’t know, I guess I was just sort of...”

I stopped myself, embarrassed. Despite everything I’ve argued here, I felt mortified, rattled to the core over what she might think of me. I thanked her, we got off the phone, and as penance I drowned myself in the most non-sexual writing I could think of off the bat: a full week of Franzen.