The experience of hearing something for the first time and then hearing it again several times soon after is called “The Baader-Meinhof phenomenon,” though my own most enduring experience of it can be more accurately described with words such as “curse” or “haunting.” It stands to reason that at some point, the newness of the word, name, or idea wearing off should strip it of its ability to startle the one experiencing Baader-Meinhof. Yet I am caught off guard and made to feel exposed anew every time I hear the name Susan Sontag, made to agonize over her absence from my body of knowledge.

Jamie Parra was the first person I heard say her name. It was January of 2006 and we were among the fifteen students sitting in a circular formation of desks sharing our work aloud in the first and only creative writing class I’ve ever taken. The entire class was composed of American undergraduates studying in Ghana. All present were bright and sufficiently compelling on paper to be accepted into the competitive program, but Jamie’s intellect was clearly something more elevated. His reserves of knowledge were intentionally cultivated through a rapacious appetite for the kinds of books and culture that retain their value across generations but his brilliance seemed somehow inevitable too. He had a mind drawn as much by gravity as by taste to the seminal, critical, and sacred. Jamie had written something between a letter and a poem titled, “A Letter of Gratitude to Susan Sontag, Though You Will Never Read It...Because You Are Dead.” I do not recall the piece’s content, only that it was cleverer than the work of a twenty-year-old had any right to be. Jamie’s endorsement was something serious and careful enough to trust, a signal that Sontag’s was a name to know.

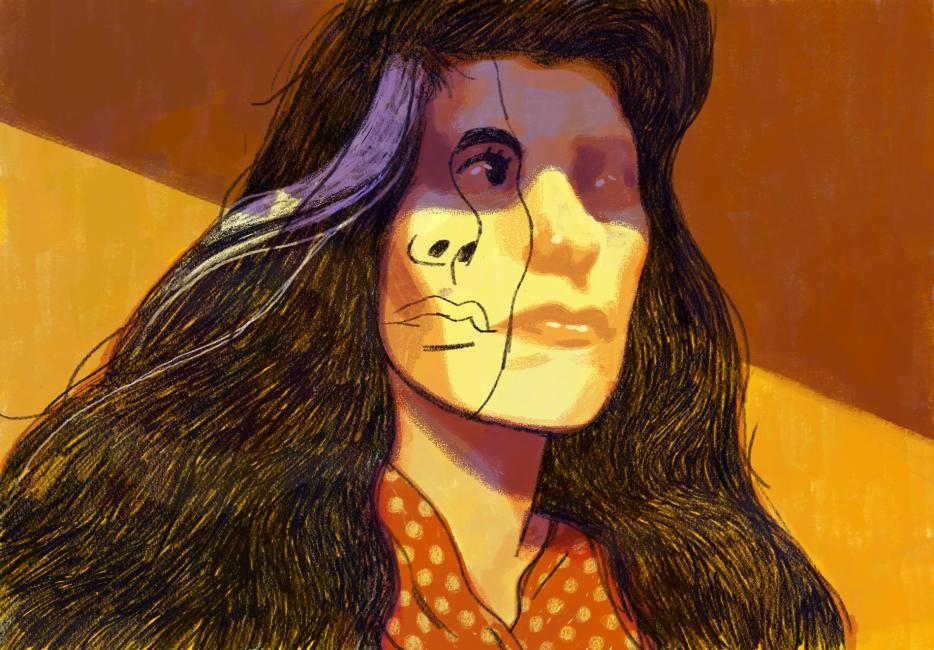

This would be confirmed in the proceeding decade that Sontag spent taunting me everywhere from book spines to pillow talk. I might be devouring a book only to see her name in a footnote and be suddenly drained of confidence that I truly understand the text at hand. I attended a reading and Q&A of a friend and author whom I admire and her mention of Sontag as an influence was the decoded riddle of why I wasn’t at her level yet. Scattered across what feels like a hundred of my friends’ homes are jackets bearing her name as part of impeccably curated libraries. Men I have loved have loved her. Reading Susan Sontag’s work is arguably the most pressing unfinished business of my career as a writer, yet I’ve avoided it for fear that witnessing its brilliance would reflect back my own inferiority.

But in the last few weeks, I’ve received a great deal of positive news and along with it, more leisure time than I am accustomed to. In that time I went to brunch with the writer Rachel Syme, another devourer and creator of culture, who mentioned in our conversation how the best writing is the kind that makes you say "FUCK!" out loud and want to chuck a book across a room. I imagined the pile of unread Sontag in my Amazon Wishlist and library queue and how often I’d muttered “Fuck” at it in dread and exasperation. But Rachel’s words transformed the potential for that “Fuck” to be a thing of awe, a challenge and a catharsis and perhaps even a relief all at once. I finally set aside some despair time in the calendar to encounter Sontag face-to-face on the page. I fully expected to lift my head to find myself buried deep in her shadow.

*

In a hollow attempt to create meaning that never manifested, I chose to begin at the end. I found Regarding the Pain of Others, her last published work before dying in 2004, online as a PDF and scrolled through the grim glow of its just indictments in the early hours of a morning in January. One of the most important stories of my career is a chronicle of my lifelong habit of watching people die online, starting with my eighth grade discovery of girls succumbing to eating disorders on blogs where I watched the narratives of anorexia as a facilitator of self-annihilation play out with envious revulsion. My story advanced across time and the technologies that made it possible for me to watch executions in countries I’ll likely never step foot in and always returned to the sick, starved girls in between. As I realized the topical parallels between my story and Pain of Others, the anticipated shame of witnessing Sontag’s sharp, acerbic critique was joined by the dual shames of moral nakedness and critical amateurishness. My story looked ghoulish and self-indulgent faced with her damning observations of the driving impulses to view and even seek out images of violence. The fact that I’d written mine unaware that so authoritative a text existed already on the topic felt like the accidental bravado of a particular kind of undergraduate male who regularly thinks he’s written a foundational piece of political theory because he’s never read, or at least never understood, the work that came before. But the devastation of learning that one’s work is unoriginal is not nearly as painful as watching the circumference of the gap in one’s knowledge expand outward from a single piece of missing literature to the limitless, insurmountable pile of works yet unread.

I moved from the end back to the very beginning, locating a PDF of Sontag’s “Notes On Camp” with the same ease as I did Pain of Others but now equipped with sufficient reverence to print the document and experience it as an object in the world, namely as a weapon against myself. By the second page, Sontag had made eight cultural references that I did not recognize. I scribbled their growing number as superscripts next to each until the piece mercifully ended on page 13 where I marked the 95th reference I did not know. They are scattered casually in the text, starting with a reference to the novel, The World in the Evening, and closing with one to the Tischman Buildings, with dozens of operas and films and philosophers sandwiched between. Whatever these references were meant to elucidate remained abstract to me in a thick absence of knowledge.

In this aspect, reading Sontag is the opposite of experiencing the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon. It is an encounter with a collection of names and ideas that go by unexplained to us and that we must actively seek out in order to encounter them again. Sitting down with Sontag at last did not feel like a faceoff with the inferiority of my patterns of thinking but of my patterns of consumption. It was accompanied by the sudden panic that it is far too late to catch up, and worse, knowing that I wouldn’t want to try to if I was given a chance. It was the realization that my disposition is such that I am at my best when I am feeling rather than learning, for better or for worse.

In practice, those bewildering minds that consume, digest, and accumulate as intellectual fuel a massive portion of the world’s scholarly and artistic output are indistinguishable from the supernatural. I suspect now that Sontag had the power to freeze time for weeks on end to read whole author catalogues and view entire film oeuvres then snap us mortals back into reality and we were none the wiser that we’d just missed the feast. I certainly envy the resulting arsenal of wisdom that this superpower bestows. But I despair already that time proceeds at the pace it does, uninterrupted on its march into the infinite. Enduring still more of it would function as nothing short of a curse.