The Case of the Grinning Cat will be screened at the TIFF Bell Lightbox in Toronto on May 19.

“It is a great asset in life”, Chris Marker observes dryly in The Case of the Grinning Cat, “not to know what you are talking about.” And it might be a great asset, likewise, to not know what Marker is talking about: his was always a cinema of roving curiosity, more interested in posing questions than in seeking out answers. He is often credited with pioneering the art of the essay-film—as he once said himself, “film is a system that allows Godard to be a novelist, Gatti to make theater, and me to make essays”—but if this is true it is more to the traditional meaning of the word, “to attempt”, than to any kind of long-form explanation or argument. Marker’s filmed essays represent attempts: they look at the world not with expertise or a pretense of understanding, but with the desire to explore its nuance and character, endeavoring to look and listen and watch.

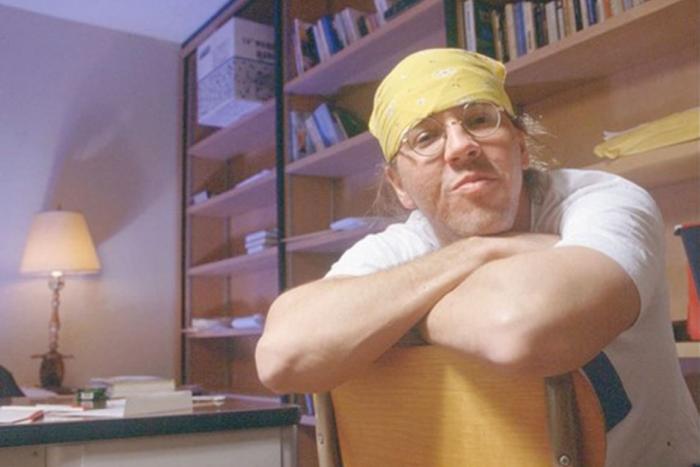

Staring out at the world around him with endless curiosity—is it any surprise that Chris Marker loved cats? The filmmaker’s beloved (and somewhat infamous) orange tabby, Guillaume-en-egypte, appeared in many of Marker’s films, including at least two shorts in which he himself is the star. But Marker also considered Guillaume a kind of personal avatar or stand-in for the filmmaker’s own image, often opting to present the cat’s now-iconic cartoon likeness in place of an expected artist’s portrait. This may have been a simple case of reticence and reservation masked by self-styled authorial mystique, but doesn’t it also seem likely that Marker truly considered himself better represented by the animal with whom he shared so much in common? As a documentarian, if one can truly call him one at all, he sat perched on the edge of the action, observing it from a distance, ready to pounce but quite content to idle; one can even imagine the sage-like but slightly coy narration that became a trademark of his work belonging to a cat in awe and bemusement of his strange but familiar environment.

The Case of the Grinning Cat, though not widely considered among his most seminal films, nevertheless remains one of the most purely fascinating—one might even say it’s his most curious. The last feature he made before he passed away last summer, at 91, The Grinning Cat arrived in 2004 in the form of a video documentary made for French TV, but in every way that counts it is purely cinematic. The film begins, as many of Marker’s do, with the observation of a strange ritual: here it is the formation and execution of a complicated flash mob in Paris, in which dozens of strangers meet in a city square and, at a precise time during the afternoon, begin opening and closing their umbrellas at timed intervals. Marker tracks the flash mobbers on their brief escapade as if he were observing a strange foreign custom, soaking in the details of the event and the reactions from delighted and confused onlookers as if to point and say, isn’t the world we live in utterly odd? He regards these people in much the same way my cat regards me as I type this piece: he may not understand the purpose, but he enjoys the movements all the same.

Marker follows the flash mob through town until he stumbles upon a more salient point of interest tucked away in the periphery of the frame, as though accidentally uncovering a clue: a canary-yellow cat’s face with a massive cheshire grin has been painted across the side of a distant building, a wide-eyed observer perched high above the city. And this peculiar emblem, it soon becomes apparent, is not the first of its kind, as Marker discovers a veritable glaring of graffiti felines strewn about the Parisian streets. This quickly becomes the film’s central mystery: the swarm of smiling cats are made an obsession for what seems a kind of conspiratorial intrigue, transcending their painted roots to seem like not so much Banksy-esque street art installations as almost Pynchonian omens—strange tokens of portent connected to something bigger than none of us can see.

One of Marker’s unique gifts as a filmmaker is his ability to invest these minor urban anomalies with a kind of exaggerated fantasy allure, though without recourse to expected docu-drama trickery. He so deftly teases out connections between seemingly benign or irrelevant details—a cat who lives at a subway station, a fleeting celebrity scandal, mass demonstrations on election day—that one begins to suspect all of Paris is under the invisible control of the grinning cat’s cheshire smile, which appears in the least expected places with almost too-convenient regularity (it has been suggested elsewhere that Marker himself may have been responsible for the cat graffiti phenomenon, not simply documenting its arrival but encouraging or facilitating it somehow too). As the yellow cat finds its way onto signs and billboards and masks in the midst of student protests, Marker takes the opportunity to explore the landscape of the new world’s half-hearted “militant” left, a meager assortment of youthful protesters taking as a stand as a matter of mere posturing. Marker, like the cat, takes stock of the movements without judgement: he observes the huddled masses and their empty rhetoric, sympathizing with their desire to take action but dispirited with their lack of conviction or commitment.

And yet The Case of the Grinning Cat is not, despite its foray into the protest movements of the modern French youth, an explicitly political film, remaining more interested in the fabric of contemporary culture, cats and all, than in one particular facet of it above others. In the course of tracking what appears to be a deepening citywide mystery, Marker finds himself surveying the French election (in which the unsure left is galvanized only when threatened by a burgeoning extreme right), the reaction of the French youth to George Bush at the outset of the Iraq War (which leans more reactionary than you might have seen in American youth groups at the time, though Marker suggests also perhaps less informed), and a host of other social and political happenings popping up around the city to keep the populace properly stimulated. One has to wonder if Marker—who, we should remember, was active during the student protests of May ‘68—had not, by 2001, grown somewhat weary of tracking the developments of youth protest movements since his own halcyon days. He spent a year scouring the city for appearances of his beloved yellow cat, but had he not in effect been following the same journey for almost six decades as a filmmaker? Had his curiosity not been burning on all this time?

If there is one thing far too many contemporary documentarians lack, it’s the same thing too many contemporary film critics lack: a sense of curiosity and a desire to question. We are inundated with work which aims to argue and illuminate, essays and articles and films which hope to explain the world to us. But explanations are by nature reductive; every articulation of an idea fails to account for some of its nuance. That’s why Chris Marker’s essay-films remain such endlessly valuable resources to those who want to know more about the world we live in: the films themselves reflect that desire to learn, and their curiosity about their subjects make them infinitely wiser and more sophisticated than any number of films which offer answers or solutions. We do not discover, by the end of The Case of the Grinning Cat, the real answer of why the cats had appeared and what they were designed to achieve. But we do discover much else.