This morning’s edition of our Shelf Esteem column by Emily M. Keeler featured an ‘as-told-to’ style interview with David Gilmour, the award-winning Canadian novelist who also teaches literature at the University of Toronto. In the article Gilmour shares his opinions on women writers (“I don’t love women writers enough to teach them, if you want women writers go down the hall. What I teach is guys.”), and his lack of enthusiasm for Canadian literature. It didn’t take long before a tempest came thundering over Twitter. And within a few hours his comments were reported elsewhere in the media (here, here, and here, for example).

Gilmour has since suggested that his remarks were merely "tossed-off" and taken out of context in an interview with Mark Medley of the National Post. And that he was joking. It bears pointing out that the 'as-told-to' style in which we publish our Shelf Esteem column is a common journalistic format, foregrounding the subject in a loose, conversational manner intended to feel more direct and intimate. We omit the interviewer and edit the transcripts for length, clarity and flow, always mindful of context. In the case of the Gilmour interview we did not leave out anything he said that would have qualified or elaborated on the comments that have proved controversial.

Given Gilmour’s claim that his comments were taken out of context we are publishing the complete, unedited transcript of his conversation with Keeler, small talk and all. Readers can judge for themselves.

- Chris Frey, Editor-in-chief

--

Emily M. Keeler: So the way it usually works is I just ask you a couple questions about the books in your bookshelves.

David Gilmour: Great.

Keeler: And then you tell me a little bit about them, it’s pretty painless.

Gilmour: That sounds just perfect. We’re gonna be in and out in fifteen minutes?

Keeler: We can do it that way.

Gilmour: Beautiful. Great.

Keeler: For sure.

Gilmour: What kind of a magazine is this?

Keeler: Hazlitt is an online magazine, it’s run by Random House Canada—

Gilmour: Great, good for you.

Keeler: It’s not bad.

Gilmour: No, it’s a way into the publishing industry.

Keeler: Oh, I don’t want to work in publishing. Well, I do work in publishing. I have a magazine called Little Brother, it’s a literary magazine.

Gilmour: You’re working in two literary endeavours, that’s a curious activity for somebody who doesn’t want to be in publishing.

Keeler: Well, I don’t want to be like—I don’t want to work at Random House. That’s not the end goal, so. [Giggling]

Gilmour: What is the end goal?

Keeler: I’d like for the magazine to take off. That would be sweet. That’s probably wishful thinking. I don’t know. I’m also a freelancer. The book world is kind of my beat. I also write for the LA Times, and The Globe and Mail and stuff.

Gilmour: As a photographer or writer?

Keeler: As a writer.

Gilmour: Well, great. Well, just help yourself there love.

Keeler: Well, give me the tour. How do—

Gilmour: Well, there’s—I can’t really give you the tour. These are all the translations of my books. All these things here, including the audio book. There’s everything from Brazil, to Japanese, to Greek, to um, Korean, to Bulgarian, to Vietnamese, to Dutch, to Hungarian, to Russian, to Norwegian.

These are of course the treasured Proust, that’s one of my great joys, not only having read Proust but having read him twice, and having listened to the audio CD twice.

Keeler: Would you recommend the CD?

Gilmour: It’s brilliant. There’s two versions, one’s 50 hours and one’s 150 hours. I’ve listened to them both, and they’re both dazzling. And these are just more translations of my books, these are all the German translations. Um, this is the Tolstoy section, Tolstoy, Tolstoy, Tolstoy, and then Chekhov. So I would say the three big hits here are Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Proust would probably be—because as you can see there’s Tolstoys all over the place.

Keeler: [Giggles] From what I understand you’re quite the fan—

Gilmour: And my library is unfortunately in storage, because I just moved. I’ve just moved. So what you’ve got there—and I’ve got some English-language versions of my novels there too, but mostly, mostly, they’re the translations. A lot of them, well, the thousand, twelve hundred books I’ve got, whatever, are in storage.

Keeler: So this is a very, very small selec—

Gilmour: Well, this tends to be, yeah, this tends to be what I teach. What I teach from, this collection here.

Keeler: [Noticing a copy of Sheila Heti's Ticknor on the shelf] Did you teach Sheila?

Gilmour: No. Shelia gave that to me as a present because I did a little radio thing on her, and I interviewed her for the radio and she gave me a very sweet book [the novel Ticknor], it was a very sweet dedication, I think.

Keeler: Can I see it?

Gilmour: Sure.

Keeler: Sweet. I love this book. Are these your annotations?

Gilmour: Yeah.

Keeler: Do you mark up all the books you read?

Gilmour: [Whispers] Yeah.

Keeler: Yeah? Cool. Can I ask you to hold this, just so I can get a photo of the dedication?

Gilmour: I don’t want you to, no.

Keeler: [Laughs]

Gilmour: It’s private. That’s for your amusement only.

Keeler: Ah ha. Cool. So you only keep the books in here for teaching purposes.

Gilmour: Yeah.

Keeler: Do you have a favourite volume of Proust?

Gilmour: Um, I do actually.

Keeler: Is there one you revisit a lot?

Gilmour: I like volume four, Sodom and Gomorrah is the most entertaining because it’s the funniest.

Keeler: What’s funny about it?

Gilmour: It’s very, very funny about human vanity. Particularly gay vanity.

Keeler: Yeah, I haven’t got that far.

Gilmour: And, uh, Chekhov of course, because Chekhov was the coolest guy in literature. I really think he is the cool—there’s three volumes of his there, he’s also a great-looking guy. Um. And he is the coolest guy in literature; everyone who ever met Chekhov always somehow felt that they should somehow jack their behaviour up to a higher degree. He died very young, but he aged very quickly because he was ill, he had tuberculosis and he died at 44. So he always looked older, well beyond his age.

Keeler: What do you mean when you say that he jacked everyone up?

Gilmour: Well, he had a personality that was such that everyone wanted to behave a little bit better than they behaved normally when they were around Chekhov, because they wanted him to think well of them. Because he was so graceful, and so gracious, so generous in his—in his dealings with people. He believed in kindness, and he hated bullies. And he—no matter how famous he became—which was very famous by the time he was 28—he never, uh, he never played the rock star. He had a huge bellicose laugh, it was so loud that they sometimes would throw him out of restaurants. He had such a good time laughing.

Keeler: Well, this is a pretty nice view.

Gilmour: Yeah, it really is. I got this job six or seven years ago, now. Uh, when The Film Club came out. And they said they’d try me out for a semester because they wanted [inaudible]. Normally you have to have a doctorate to teach here, but they asked if I was interested in teaching a course, and I said I would. It worked out. I’m a natural teacher, I have a natural aptitude [inaudible]. I was also trained in television for many years. So I knew how to talk to a camera, therefore I know how to talk to a room full of students. It’s the same thing.

Keeler: And The Film Club is also kind of about you being a teacher.

Gilmour: Yeah, it’s about me teaching my son about life and the world through film. I’ve got a copy of it down there.

Keeler: So do you teach mostly, I guess classic lit, or Russian?

Gilmour: I teach modern short fiction to third-years and first. So I teach mostly Russian and American authors. Not much on the Canadian front.

Keeler: That’s too bad.

Gilmour: I know, it is, but I can only teach stuff I love. I can’t teach stuff that’s on that curriculum, and I just haven’t encountered any Canadian writers yet that I love enough to teach.

Gilmour: Come in!

[A student or colleague of Gilmour’s comes in. They speak to each other in French.]

Keeler: I notice that you don’t have many, like, books by women.

Gilmour: I’m not interested in teaching books by women. I’ve never found—Virginia Woolf is the only writer that interests me as a woman writer, so I do teach one short story from Virginia Woolf. But once again, when I was given this job I said I would teach only the people that I truly, truly love. And, unfortunately, none of those happen to be Chinese, or women. Um. Except for Virginia Woolf. And when I try Virginia Woolf, I find she actually doesn’t work. She’s too sophisticated. She’s too sophisticated for even a third-year class. So you’re quite right, and usually at the beginning of the semester someone asks why there aren’t any women writers in the course. I say I don’t love women writers enough to teach them, if you want women writers go down the hall. What I’m good at is guys.

Keeler: And guys’ guys, too.

Gilmour: Yeah, very serious heterosexual guys. Elmore Leonard. F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chekhov, Tolstoy. Real guy guys. That’s a very good observation. Henry Miller. Uh. Philip Roth.

Keeler: What Henry Miller do you teach?

Gilmour: [Inaudible] to the third year class, and to the first year class I teach Tropic of Capricorn. Sorry, Tropic of Cancer.

Keeler: How do they react?

Gilmour: They’re shocked out of their pants. Nobody teaches that book except for me. Sometimes their parents actually question me about it, they say, Listen, this is really outrageous. I say, well, it’s a piece of literature that’s been around for 60 years... so it’s got something going for it.

There’s an even dirtier one that I teach, by Phillip Roth, called The Dying Animal. I save it ‘til the very end—I save that ‘til the very end of the year because by that point they’ve got fairly strong stomachs, and they’re far more sophisticated than they are in the beginning. So they can understand what the difference between pornography and great literature is. Um, Philip Roth’s a great piece of literature. There are men eating menstrual pads, and licking menstrual blood from [inaudible] and by the time my students get to that they’re ready. Roth has the best understanding of middle-aged sexuality I’ve ever come across. Now where’s my copy? I took it home to read it again, and I think I might have packed it up and stuck it away in um storage. ‘Cause I’m trying to buy a new condominium. And so I put everything in storage so that I don’t get in too big of a panic. Yeah, damn, I’ve done that. That’s going to be a problem, because all my favourite parts are underlined.

Keeler: [Laughs] Do you ever worry that teaching is going to kill your love for any specific book?

Gilmour: Uh, no, ‘cause I teach only the best. And what happens with great literature is that the shadows on the pages move around. So you read it when you’re 46, and you read it when you’re—I’m 63 now, and it’s moved. Great literature organically moves, and it never stays still. You don’t get actually tired of it, you just notice different things about it. What is intolerable is second-rate and third-rate literature, because it gives up all its secrets the first time by. And the second time you read it, it’s all there; there’s nothing new. It’s like an Andy Warhol painting—you look at an Andy Warhol painting once, you can look at it a hundred times and never see anything new in it. But I’ve read War and Peace four times, and I’m still breath-taken with how much good I hadn’t noticed the other three times.

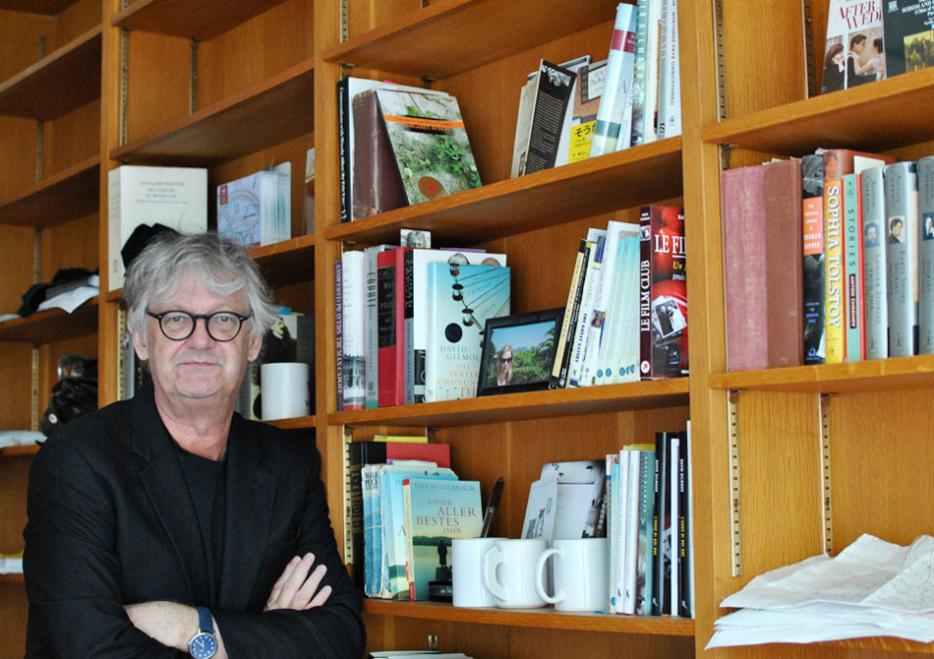

Keeler: Do you mind if we take a couple of posed shots?

Gilmour: Yeah. Let me put a jacket on.

Keeler: Okay.

Gilmour: I don’t get to wear my Armani jackets very often.

Keeler: [Laughs] Might as well.

Gilmour: Well, as soon as I get into class I take it off so nobody ever sees how great it is.

Keeler: Absolutely.

Gilmour: Okay, so where would you like me?

Keeler: Can you stand right in front of this here?

Gilmour: Yep.

Keeler: Excellent. Just wanna get the most books per square pixel here. Double-check that your glasses aren’t giving off crazy light.

Gilmour: Are they?

Keeler: Yeah, a little bit.

Gilmour: I got another pair here. These—they’re not—these give off less light, I don’t know why.

Keeler: Oh yeah, that’s way better, I can tell already. I’ll stand back over here so I get more. Let’s take a check here. The card’s full so it takes a little while. Oh yeah, I think we got a good one.

Gilmour: Great.

Keeler: Awesome, so I think that’s it for me.

Gilmour: Well that’s perfect.

Keeler: Is there anything that you specifically wanted to plug before—

Gilmour: Nope.

Keeler: Nope? You’re good? Alright.

Gilmour: Uhh, yeah, I got uh, I just got nominated for the Giller, if you want to plug that.

Keeler: Yes, congratulations!

Gilmour: Just if that’s gonna sell any books, plug it.

Keeler: It’s pretty exciting.

Gilmour: Well I’ve been nominated for a lot of awards, and I’ve lost a lot of them, so I don’t even go to square one. All I need is the cheque.

Keeler: [Laughs] I did this column with Linda Spalding the day it was announced that she won the Governor General’s, it was really fun.

Gilmour: Yeah, I won that in 2005. That was really a blast. I tell you, that was one of the best phone calls I’ve ever got in my life. Because I felt with that book, it’s a sink-or-swim book. If that book hadn’t succeeded, I knew that my publishing career might be over, that people would just not take another chance on another book. And the book had gone up and then was just starting to settle back to earth. And I thought, shit, it’s gonna—it’s tanking. And then I won the award and it turned it all around. But I’m telling you, when I got that phone call it was like it saved my—it felt like it saved my entire literary career. I felt, if this book tanks like the book before it tanked, I’m fucked. And indeed.

Keeler: You’ve had a pretty like, long—

[Recording ends]