In a cemetery high up in the Bronx, close to the Throgs Neck Bridge that connects the northernmost city borough to Long Island, a family lies together in a single plot more than twelve miles from home. Their collective grave bears the mark of irregular but consistent tending. The afternoon I visit, a bouquet of purple and white flowers covers part of the gray headstone, a cross carved at the top, just above the family name: Crimmins.

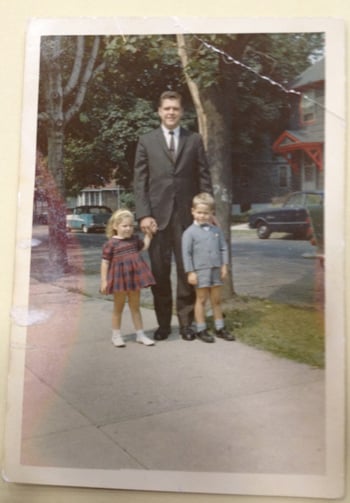

The children lie deepest in the ground. Born a year and a week apart in October, Eddie and Missy died on the same July day in 1965. Lying above them is their father, Edmund. He outlived his children by nearly fifty years.

All but one of the Crimmins family are dead now. Alice, Eddie and Missy's mother, is out there somewhere. For decades she lived in various parts of Florida. Other times she lived on a yacht bearing her name. More recently, after her second husband died, rumors placed her back in the Queens neighborhood she fled, nearby Nassau County, or somewhere along the Metro-North's New Haven line. Nobody knows. Everybody speculates.

People are experts at speculating about Alice Crimmins. They've had so much practice over half a century. It’s hard not to, when her story will never have a proper ending.

*

At the New York City Municipal Archives, in a musty old building a few stones' throw away from the Brooklyn Bridge, City Hall, and several courthouses, a gentleman archivist I'll call Reg shakes his head. “They're telling me you can't have the box. It's ridiculous. We never had a problem before.”

“What seems to be the issue?” I ask.

He waves his hand. “Some new person, doesn't understand how things work around here. Let me go talk to somebody. He'll be able to sort it out.”

I wait a few minutes, then a few more. The truth is I'm already further ahead than I thought. I figured there would be court transcripts, affidavits, and other relevant documents, secrets hiding in plain sight as they so often do in old buildings housing city archives. Anything else pertaining to the case is like extra gravy on a succulent turkey. Keep your expectations close to zero, I tell myself, and then be pleasantly surprised.

Reg returns with a long rectangular box and sets it on the table in front of me.

“Here it is. Shouldn't be a problem from now on.”

He leaves the room again, this time to retrieve the boxes of documents I requested. Left alone, with surprising nervousness, I open this box. My hands shake. A thrilling jolt pulses through me. Because it feels, somehow, wrong.

Alice knew her defiant attitude was what set people against her, but she clung to it because, as she told Gross in 1971, “they wanted me to break down. They wanted me to grieve—not for the sake of my children, but for them—the police. I wasn't going to give them the satisfaction. They were my kids. Nobody was out looking to see who killed my kids. They were interested in making me break.”

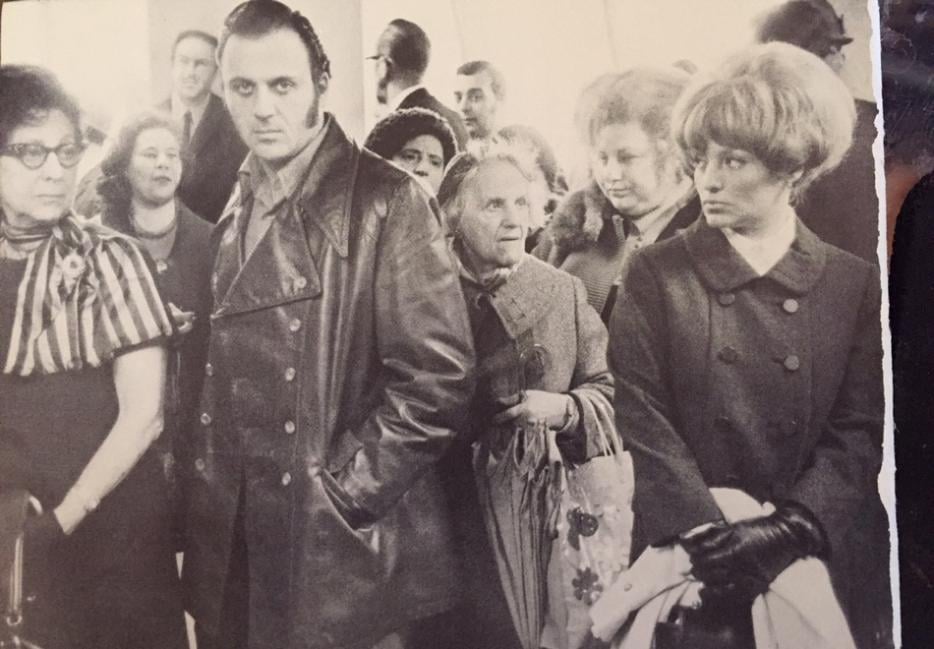

She broke, over and over again, whether questioned directly on the stand in her first trial, through years of phone taps, being asked to leave jobs after her employers found out who she was from police, and continuing to drink too much, laugh too hard, and take too many lovers instead of acting like the stereotypical sobbing, grieving mother. In the immortal words of Cole Porter, “Why can't you behave?” Alice Crimmins didn't, until she had no other choice.

*

I return once more to the Municipal Archives. I ask Reg to bring out the box of evidence again. I touch Missy and Eddie's bloodstained clothes, Alice's telephone books and doodle-laden diaries, Eddie's kindergarten notebook filled with his first printed words (“Missy” prominently among them), blood and hair samples encased in slides. The feeling of wrongness has subsided, replaced by a more curious question: can I possibly understand Alice Crimmins through these objects?

The clothes don't help, nor does Eddie's notebook. They touch too raw a nerve, even after fifty years. The telephone and address books carry an opposite, more remote feeling. The book emblazoned with Anthony Grace's name carries a sense of unresolved longing. Did they love each other? Or did they marry because there was simply no other option for the millionaire contractor and his notorious mistress once their names were inexorably bound by courtroom testimony?

The only thing that pierces Alice's hard-won, tortoise-strength shell and brings me closer is a simple doodle. The woman angles her head down, to the left. In that same notebook there are other similar, incomplete versions of this doodle, accompanied by untold scribbles in the margin. This cartoon woman carries a whiff of loss, of retreat, of wanting to find some sliver of self while the psychological walls closed in. Here is Alice, a little bit of her, more than any interview, any recording of her voice, any videotaped footage could ever provide.

*

Few people connected to the case are still alive. Sophie Earomirski moved with her family to Florida and died there in 2009. Joe Rorech's financial problems continued to mount, and he died in obscurity in 2006. Tony Grace died in the rich Westchester suburb of Harrison, New York, where one of his sons still lives, in 1998. Edmund Crimmins remarried and relocated to Leesburg, Florida, where he died in 2012, a few days after his seventy-sixth birthday.

Anthony Lombardino still practices law in the Queens neighborhood of Richmond Hill. A mere five years after Alice's first conviction, Lombardino walked his behavior back: “I don't know if she did it. It still seems unlikely. I can't believe it. I don't even believe the story I told the jury. I don't even believe it now.” (In a telephone conversation earlier this week, Lombardino denied he made these comments. He also called Gross, who included the comments in his book, “a liar,” and held back more vituperative comments because I was “a lady.”)

For all intents and purposes, the only person left to care is Alice Crimmins. Now seventy-six and long living under a different name, she hasn't spoken to the press in more than four decades. (That includes me: she did not return repeated voice messages.)

The lawyer and true crime writer Albert Borowitz, in his 1991 account of the case, wrote: “If the Crimmins case is viewed with the hindsight of the 1980s—when a young mother with a strong sexual appetite is less likely to be pronounced a Medea—it seems that Alice is entitled to the benefit of the Scottish verdict: Not Proven.” Two and a half decades later, the Scottish verdict still seems to be the right call, even if it is the most frustrating one. The polarized debate about Alice would not die down if she spoke up today and revealed what she's been up to for the last forty-odd years. It would only worsen in the current, public shaming-happy climate; more would believe her, but yet more would condemn her.

The Alice Crimmins case seems to turn everyone connected to it into a guilty party. From Sophie Earomirski wishing to tell her version of the truth, to Jay Piering and his fellow detectives judging Alice's lifestyle, not the evidence, while laughing over wiretaps of Alice sleeping with her lovers, to an entire society understandably discomfited by the idea of a mother murdering her children for some perverted sense of freedom. And me, adding grubby fingerprints to evidence that could have yielded tangible forensic truths, if anybody cared enough.

Perhaps if the evidence stored at Municipal Archives had been properly secured, primed for a fresh look by authorities more understanding of a woman's right to live her own life, we might know, doubt-free, who killed Eddie and Missy Crimmins. We won't. It's too late. The looking glass clouded over the night Alice Crimmins's children died and it has reflected back fog ever since.