The Oversights began two years ago in response to undisclosed “threats from beyond the settlement borders.” The initial bans were so minor hardly anyone protested them—townsfolk were no longer allowed to take specific hallucinogens that would lead to mouth or bottom purges, to carry certain brands of Boomboxes or to belt certain guilty pleasures in the presence of certain strangers. Gradually they were banned from drawing, painting, or collaging bodies in specific acts of combat (Olympic wrestling, Thai kickboxing), and then from screaming, crying, or complaining about migraines, tooth aches, gastric cramps, influenza, or muscle ruptures. The Lions aim to distinguish the residents of Parádeisos, a well-manicured resort town, from their neighbours to the north, occupants of a freewheeling city called Kir. And today, April 14, 2017, the Ultimate Oversight is coming into effect.

“We must hold all liquids and feelings inside,” the Archon Lion said last night in an interview on the town’s one television station, of which he is the sole owner and stakeholder. “We are the elegant sons of Parádeisos. We don’t want to be like the scum of Kir, with their fat, unchecked libidos, fornicating and peeing all over their own countryside.”

So overnight it was carved into every lovage lawn in town, painted on every bus shelter: Intimacy will no longer be tolerated. All speech not considered by the Lions to be “small talk” will be punished via the Shallow Awl, that, when inserted into the offender’s temple, pilfers one insightful thought from his or her brain forever. Touching of any kind will be punished with proportionate electrocution and/or “Act-outs.” In these, a Strategos Lion, one rank below the Archon, is tasked with recreating the sin to an extreme with its perpetrator.

Antera is sixteen. She grew up reading romance poetry and play-fighting with her older brother, George. This new world, forcing through her television speakers, through her father’s squad radio, is not one in which she anticipated her adulthood unfolding.

She etches If I had known into a Posture Bench at the town waterpark. It’s July, and she has taken the neighbours’ girl and boy, Kardiá and Méllon, there to play. Before this summer, pocket money was always in abundance for the daughter of a police officer. But she accepted this job when it was offered because the idea of safety and security, even for well-born, faithful people, is now being eroded. And the neighbours are hiding a handsome young exile in their attic.

I would have gone to Eudaimonia and swallowed every plant with neon blooms. I would have tongue-kissed every boy who looked at me. I would have walked on lithium fire.

All exhilarating rides in the park have been shut down; the only ones still operating are the flume ride, at half speed, and the lazy river, its inner tubes slightly deflated. The others hulk, ghostly, beside unplugged first-person shooter games and gyro stands that only serve pita and beef, no hot sauce, no onion, no tzatziki. Despite this, the park is crowded.

Kardiá starts to scream, and when Antera looks up from her wood poetry she sees a streak of red coming from the child’s downturned nose, darkening the plunge pool. Antera knows these two are too young for the waterpark, but if she doesn’t take them now they may never have the chance to go. And she will have to hold the guilt of that lost opportunity forever.

She runs to them, her left anklebone hissing with Enforcement Static. She is breaking two rules: Townsfolk must not sprint in public except for sanctioned athletic competitions, and townsfolk must not come to the aid of weaker civilians. Reaching the edge of the pool she calls for the children to swim to her, and her lips spray orange static into the water.

Antera lifts the children out of the chlorine and deposits them onto the blistering pavement. All three crouch like toads. She asks Kardiá, “Are you in pain?” and the girl looks confused. This would once have been an answerable question to Antera, but to a four-year-old girl the only legal response is “No.” Méllon comes to put his arm around his sister, making her look even smaller. For a moment Antera fantasizes about drowning these innocent creatures right now, in the sun, before things become intolerable.

Instead, she tells the boy, “You need to keep your hands to yourself. Someone might see you.” I would have gone to the Mageía Forest and hunted an elk with a longbow. I would have roasted the thickest cuts with amaranth oil and offered a basket of offal to my dear parents.

Antera sees a Hoplite Lion plodding toward them. He is holding up a golden flag, meant to signal an infraction. “I want to go home,” Kardiá says, the line of blood now reaching her chin’s indent. Antera longs to wipe the girl’s face clean, but the Hoplite Lion is standing over them. He commands that they stand, too. His mask is made of papier-mâché, declaring him a new recruit, and this frightens Antera more than a titanium mask would have.

“I’m a very nice man,” he says. “So I’m going to pretend I only saw that last breach.” He puts his arm around Kardiá as an illustration, and turns to Méllon. “Do you know what happens now, son?”

In the mess of papier-mâché, Antera sees eyes demanding privacy. And right now she can only lessen the boy’s suffering by doing what she is told. “There’s a high-diving show on the mountain later,” she says to Kardiá. “Do you want to watch the swimmers set up?”

The girl tidies her wet, lemon hair into two long fishtails and smiles with all her temporary teeth. “Watch how brave I can be,” she whispers to Antera, and then, as if coached to do so in an emergency, she says to the Hoplite Lion, “Thank you for taking your job seriously, sir.”

Antera turns once as they walk away and sees Méllon’s little body flare white and enlightened, holy as an unwilling saint.

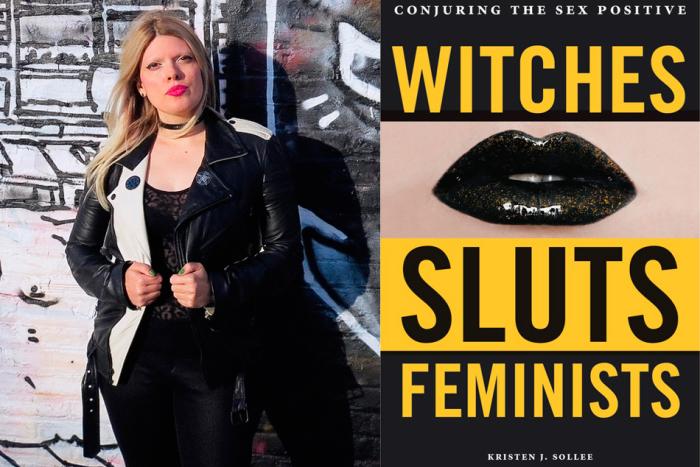

Beside the mountain, Antera spots the handsome young exile. He wears a leopard-print swimsuit and is older than she is, at least twenty-five. Antera is used to men like her father, dense and woolly, and is startled by how lean and greased this one is. From her parents’ heart-to-hearts across the kitchen table she’s gathered he’s an illegal runner from Kir. Why would anyone choose to come to this colourless place? She imagines the rest of the world to be full of women pulling blushed apricots from softwoods and jungle cats tearing across meadows made of green silk.

The illegal runner bends to tug a copy of the town paper, The Democratic Times, from the beak of a mechanical bird in the water below the mountain. The paper is soggy and it tears without a struggle. The bird suddenly seems sentient; it ascends from the water and muzzles the runner’s bronzed neck, then widens its wings in a gesture of intimidation before attacking.

Causing damage to any government-owned property, including every ride and adornment in this waterpark, has been banned by Oversight, so the runner can’t fight the bird. He huddles down, using his spine as a bone shelter. Blood blooms through the splinters in his back, the gashes on his hamstrings. Wandering past this chaos is a group of vacationers gleaming with Liberty Glitter. For the price of four high-end steak dinners, or bail after a Loose-Speech arrest, visitors can buy this body salve to protect them from a variety of minor Oversights. A few of the vacationers scream painlessly as they notice the bird attacking the runner. Antera covers Kardiá’s ears, not wanting to explain this particular inequity.

The runner faces Antera. His eyes cut clean lines toward her, but he does not move. His expression becomes blanker, and as it does the mechanical bird’s attack slowly grows less violent. When the runner’s face is completely inert, so too is the bird.

Antera asks Kardiá to wait in the dark-spill of a mastic tree. She walks over to the runner and raises her sweaty, teenaged palms to hover beside his cheeks. “I’m your neighbour,” she says, choosing her words carefully to avoid the Shallow Awl. “It’s nice to meet you.”

The runner introduces himself as Alp. He seems friendly, so she asks if he wants to come to her house for dinner. “My mother cooks game, and my father brews table wine,” she says.

He doesn’t think about it. He tells her no. Antera moves her hands away from his cheeks and hides her red face in them. “I’m sorry,” he says, more softly. “But that would be a very bad idea.”

Antera feels like the whole warring world has suddenly congregated in her belly. Nauseous, heavy, she can’t stand in front of this handsome man any longer. She staggers back to the mastic tree and lifts Kardiá into her arms without thinking. Shockwaves rocket up to her heart. “We can go home now, sweet thing,” she says, reluctantly letting go of the child again.

“What about the high-diving show?” the girl asks.

“We have no time to wait.” Antera storms to the Post-Punishment Office at the waterpark gates, making sure Kardiá is following behind, and there she collects a sniffling Méllon. His white shirt now has holes in it the size of cigarette burns, but she is in no state to offer comfort. She casts her shadow on the children as they walk down the dirt road into the dipping sun.

Antera is lying on her single bed later that evening, in a pressed crepe nightgown and plain weave socks, while the sounds of a horsemeat dinner party fluster the floorboards. Her mother is playing the lavouto and her brother, George, is crooning a sanctioned ballad to the neighbouring family—the two parents, Kardiá, Méllon. Antera has been listening carefully and has not heard Alp’s low voice, although that could be a testament to his stillness and not to his absence.

Antera told her parents she was ill, attributing the heat of her sunburned forehead to a tropical fever. George fixed her a plate of wafers and mandarin preserves, and it rests untouched on the bedside table. Below her he is singing, For if I ever step foot on faraway soil, it will be because the whole ocean has boiled, it will be because every road has coiled. She wets a wafer on her tongue, then turns it into paste against the roof of her mouth.

She lets herself imagine escaping with Alp, tying his hands with wire, gagging him with dishrags, hitchhiking. Shivers map the insides of her thighs. These thoughts, are they intimate? Or would the Lions consider them Harmless Individual Fantasies? The Oversights make no specific mention of anything carnal, associating those words with the crude sons and daughters of Kir. Antera makes a bold guess as to what is permitted.

In the dark, she remembers the man’s face. She pictures herself kissing his lips, his coconut-oiled collar bone, the animal tuft above his swimsuit. She reaches under her nightgown and unbridles her fantasies, urgently, until her desire is material in her hand. For a beat she feels elated. And just as suddenly she is a phoenix, her body in violent flame. Of all the pains she has lived through, she has never experienced one this caustic. She wants to scream for her mother’s help, but her shame would be far worse than the physical distress.

A knock at her door, clearly audible. Antera rises from bed and goes to find out whose hand she is hearing. There is Alp in a pair of dirty flannel sweats, lanky over bare feet. He grips a jar of table wine. “Take this,” he says, handing her the drink. “And swallow it very, very quickly.”

Antera is careful not to touch him as she accepts the jar. Her body hisses with pent-up static. She has a thousand things to say and no voice to say them with. So she starts to glug the alcohol. When she tries to take a break, Alp puts his hand on the bottom of the glass and pushes it to her lips, some of the wine spilling down her chin, some spurting up into her nostrils. He only drops his hand when the liquid is gone.

“Why did you do that?” Antera whispers, between whitecaps of nausea.

“I heard something on your father’s radio.” Alp grabs her hairbrush from her nightstand, along with a compact of powder foundation and a handful of brass barrettes, and places them in her open palms without grazing her skin.

Antera begins to tidy herself as she envisions which punishment might be in her near future. Despite the queasiness, she longs for more wine to drink.

Half an hour later, Antera’s home takes on a state of shapelessness. She descends the stairs, still in her nightgown, to see her mother running back and forth between the open door and the woodstove, her breasts striking time under her Chantilly dress. George is in the entranceway, filling the house with locust clouds of forbidden words, while her father smokes a cheroot by the window. The neighbours have left.

And young Antera. Planted at the bottom of the staircase, her hair in four plaits, her cheeks still pink from pleasure despite the powder caked on top. She is watching her body; she is not living in it.

Outside the house is a fuss of sirens. Absurd in this intimate town, where every criminal can be identified by sight, if not smell––the lavender thief, the ghost pine predator, the gasoline felon. But the trucks are on her lawn, driving donuts into her mother’s fertilizer. George looks through the peephole. “Eight beasts by my count,” he says. “And they’re in full dress tonight.”

They kick down the front door, hooking George out of their way and taking over the foyer. Beyond the papier-mâché masks, they have beaded blue manes and chrome gowns with fire opal trim. They wear six-inch platform boots made of cork and spiral shank nails. These outfits tell her they are complete novices, and insecure ones at that.

Smoke from her mother’s horsemeat feast still heavies the air, but the Lions slice into it with their batons. “Sweet thing,” one of them says, cuffing Antera by the back of the neck, “you’re ours for the rest of the night.”

Antera forces all her thoughts into a toenail on her left foot. She does not cry, because she would be punished with electrocution. Her mother quietly opens the linen closet and pulls out a military cardigan, one of the ones given out by the Strategos Lions at Modest Clothing Day. She offers the arm-holes to her daughter. “We’re still proud of you,” she says, as Antera buttons the sweater.

Two Lions clutch her by the biceps and drag her out the door, while George tries to pummel their chests, trip them, tear off their masks, and ends up convulsing with voltage on the limestone tile. Her father has turned to look out the window, the smoke of his cheroot painting long veins across the glass. She meets his eyes only once she is outside. The smallest Lion forces her, palm on skull, into one of their monster trucks, panelled in wild auburn pelts. As they start to drive away, she looks in the rearview to see a tall frame filling the neighbours’ doorway. Antera is thinking: I would be a better woman if I had no desire.

“Show me your hands,” the Strategos Lion says from across the table. He is wearing a cape made of blue velvet and barbed wire, and when he looks at Antera the light between her legs turns to shadow.

She has never sat at the Culprit Desk. In school, she wins awards for her extraordinary marks in Conscience class, for her dominance in the town’s Hestia Homemaker Competitions. Still, she refuses to offer the Strategos Lion her dirty hands—she sits on them instead.

He takes out a fret saw and holds it up to reflect fluorescence from the overheads. “I will cut them off if you don’t show them to me,” he says.

Antera is alone with this man in an interrogation room lined with rock wool. The eight Lions drew bulgur stalks to see who would have the career-boosting chance to perform the Act-Out, and this Strategos pulled the longest one. The others went to their haunt next door, a tavern owned by a friend of her father’s, to throw back black salt cocktails.

“Usually this is a job,” the man says, standing to pry Antera’s hands from underneath her. “But with you, it will be a genuine pleasure.”

She feels the hands on hers become lethal, choking her wrists limp. He releases her just long enough for him to untie his cape, and she feels the neon joy of blood returning to her arms. Once the barbed wire clinks against the ground, he starts to remove his gown, his fingers feral on the fire opal closures.

“I’m sorry for what I did,” Antera says.

He tears the buttons from her military cardigan using a seam ripper, then slices her nightgown down the front with shears. What happens next is not at all like her harmless, searing exploration earlier that night. The Strategos Lion instructs her to bite down on a chew toy he has brought with him, rawhide in two tense knots. Through the sting of contact, she bites, and grinds, and gnaws; through the dry scorch, she uses her canines. By the time she feels him finish, her teeth have worked the leather so intensely her head is pounding.

He lifts his cape from the ground without pricking his skin on the barbed wire. “You’re free to go,” he says, fixing it delicately with a knot around his neck. He looks at the Culprit Desk instead of at her. “But, little girl, next time someone thicker will do the punishing.”

Antera has never felt so calm. She kisses him on the throat, and in the electricity that rushes from that touch, she is blind to her own intention—to hurt him or to hold him—because after all she is here and sixteen and mercurial, because even in the wildest bush, beasts sometimes huddle for warmth.

In the lane behind the Lion’s Den, Antera vomits into a puddle. Wafers and mandarin preserves splash their acid onto her cheeks. She bunches her torn nightgown in her fist and squats to pee on the pavement. The dull burn between her legs turns suddenly acute, like a flame in the town crater during one of the weekly Blue Movie and Belles Lettres Bonfires.

The sun is pinking the sky. Antera shakes the wetness away and rewraps herself in her cardigan. Around the corner, her father’s friend is accompanying the other Lions out of his tavern—she knows this because she can hear them laughing, listing all the stiff drinks they’ve had. She hears the Lions tramp into their Den and wills her father’s friend not to turn the corner, knowing the shame would be intolerable if he did. But then the door to the tavern closes loudly behind him, and she wishes more than anything that his familiar eyes would see her, even exposed, even in a lake of her own waste.

Exhausted, she rests on the street, and before long falls asleep. She wakes up again at mid-morning, as around the other corner Kardiá and Méllon and their mother appear, on their way to the waterpark. The two children are wearing matching shorts and tank tops, their hair neatly combed. “Antera! What happened?” Kardiá yells, and then, confused, she starts to sob.

Before their mother can turn them around, Méllon pulls out a reading stone from his back pocket and starts to inspect the puddle. “Mandarins,” he says. Their mother tears the stone from him and puts her hand over his eyes, shuddering with an electric jolt. With her other hand she tugs Kardiá close, burying the girl’s tears in her skirt.

Her children’s vision blocked, the mother looks at Antera. Her blank eyes offer no comfort nor judgment. They are two paperweights, two glass eggs, two reading stones, and though they refuse to uproot Antera’s suffering, they show her, simply, that she is not a ghost.

“Mama,” Kardiá forces out. “Antera should come with us to see the high-diving show!”

Antera wants to wrap the children in her cardigan and ferry them to a long, lush forest, where they can live untouched. She wants to martyr her ruined body. When did it get like this? Just yesterday she was running with George through the endless town meadows. He was a golden jackal and she was six years old, and they were tackling each other and laughing until their sunburns hurt, and when they came home stained with bluegrass their parents scrubbed them and shared lullabies from the insides of conch shells.

Lullabies, leopard print, Chantilly, lazy river, bone shelter, love, and love, and smothered love.

Where is Antera? Why is everything around her so dazzling, but dazzling in the black colours and the rust colours and the sounds of an orchestra tuning? Where in this tiny big town is Antera?

Kardiá’s voice drags her back to her violent country. “The show wouldn’t be the same without her, Mama,” she says. “She’s the one who told me about it in the first place.” And all the other babble of a young girl’s mouth, one that hasn’t yet learned the kinds of trouble it can get her into.

The children’s mother says, “I’m sorry, honey. Antera is not feeling very well. She’s worried it might be contagious.”

Antera looks at the mother’s plain eyes as her own grow mistier. Without making a sound the children can hear, she mouths: I’m sorry, I’m so sorry. I should have done something to stop this. I had no idea things would get this bad for your children. She’s unsure if the mother has understood, because her expression does not change. The mother gestures toward her rucksack with her neck, and from it, Antera pulls a grey sundress. She wipes the flecks of vomit from her face using her shredded nightgown and dries her privates with the cardigan; close to human, she slips into the dress.

The mother moves her hands from her children’s faces. Kardiá is no longer crying, though her round cheeks are dappled in red. The four of them head toward the waterpark, past hornet nests strangling from jacaranda trees and rye gone unruly on each of the lane’s sides. A hound is barking a few buildings over. Antera hears the firm sound of a smack, followed by silence. Then the barking starts again.

By the mountain, Antera spots Alp, his body swaying in the steam lines. As they get closer, she notices he has shaved his face. He seems especially unattainable, clean as he is. The children cheer when they see him, but softly, aware of the threat of Enforcement Static.

He pads over on his bare feet. “You came to see my show,” he says, giving individual attention to everyone but Antera.

“Of course we did, honey,” says the mother. “We’re your family.”

A Hoplite Lion steps in front of them, waving a flag in the mother’s direction and holding up four fingers. They all know what this means: In four hours, she will be punished for exceeding the bounds of “small talk.” She fixes her spine straight. “We’re going to find a seat,” she says, formally, and leads the children to a nearby Posture Bench.

Antera needs to speak on behalf of her profligate heart, but her body is too weak to risk more punishment. So she looks at Alp and says, “Thank you for the wine.”

He smiles. It’s not nothing.

In her periphery, she can see that the high-diving show is starting. Turning, she feels a different kind of surge, one she once knew intimately. It is not desire or longing, but excitement, the thrill of observing something both new and beautiful.

Five athletes perch at the top of the mountain. Gracefully, they swan dive through the shards of sunlight. They pull silk streamers behind their falling bodies, man and material a single streak in the sky, then slip through the water’s surface without even dousing the ground. Antera feels a crescendo of fear and exhilaration at the crowd that has started to form around her. She turns in a tight circle, not knowing who or what she is looking for, just knowing she is surrounded.

The divers climb back up the mountain, using its synthetic footholds, and this time Alp is with them. He winks at her from that great height, proud and lofty in his animal print. He licks his thumb to the rising north wind, and then, without hesitation, they all jump.