When I was eight or nine, my dad took me on a trip to D.C. One night, on the way to dinner, we walked by the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. Business hours had passed but, peering into the building’s windows, my dad noticed a tomahawk missile hanging on display. He pointed at it and told me, “Your grandfather did that.”

The thing I remember most about my grandfather is the left side of his head. His temple was always pronounced—like he had a permanent knot. It reminded me of a glossy, brown chestnut. I always wondered what caused it, if he had been injured when he was younger, but I never asked. My grandfather was my grandfather, and I knew about him what I knew. I didn’t think there were any mysteries: Sylvanus B. Bracy, born on March 23, 1923. From Brooklyn. He liked building model airplanes. He liked tennis; he used to play. He liked root beer and Salisbury steak with Worcestershire sauce. And he had a mysterious knot on the side of his head.

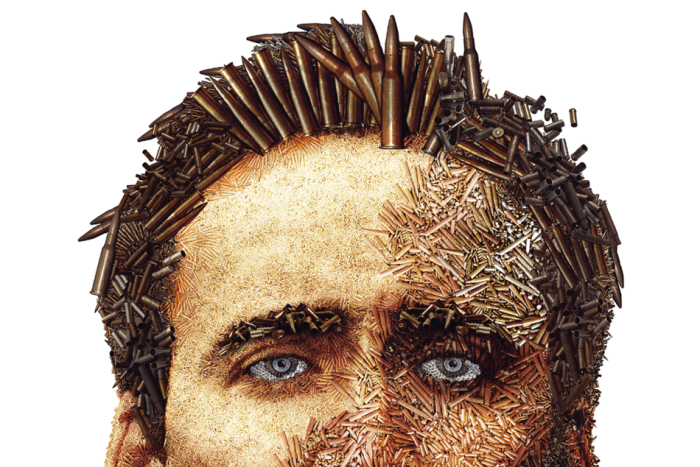

After he died, I learned that he had graduated from Howard University in 1950 with a dual degree in mechanical and electrical engineering. (Of America’s 107 historically Black colleges and universities, Howard was one of the nation’s first. It’s the highest ranking co-ed HBCU, and graduates the most Black PhDs of any college in the county.) Refused work by the aerospace industry’s entire private sector on the basis of his race, he finally took a job with the Department of Defense—which had been specifically desegregated in order to capitalize on Black brilliance—in 1953. He led teams of engineers in inventing and perfecting technology for the likes of tomahawk and air-to-air missiles, the guidance system for the world’s first helicopter that could do a loop, and the facsimile recorder computer. The patent for the latter, which was the precursor to wireless fax transmission, is the only one that lists my grandfather as one of three inventors. Suffice to say, whatever was developed for the government by their scientists belonged to the government.

My grandfather’s contributions to aeronautics had a permanent impact on the science and practice of human-powered objects literally flying through the air. But when I hear helicopters flying over my Queens apartment building, in my neighborhood with so many Black and brown bodies bustling about, I wonder who they’re looking for from so high up, what “bad dude” they’re surveilling this time. I don’t think about my grandfather.

*

Much of the way colonialism works is by gendering the colonized lands and their populations. The lands of Africa, and all its peoples, were turned hypermasculine and savage by the colonial mind. The African men, with their dark skin and their strong physiques, were too masculine, so they became animals in the eyes of their European colonizers. The women, stripped of their very femininity (but regarded as useful for breeding), were seen as inhuman, too. In perceiving African peoples as only of the body, Europeans effectively stripped them of their humanity. Regardless, whether looking at man or woman, the colonizer thought, If you’re not human, then I must be! This made him feel good and whole, and became the prevailing European rationale, carried over on boats that hauled people to America. (Maybe one of those boats brought my grandfather’s ancestors to New York.) “The Afro-American race is not a bestial race,” wrote Ida B. Wells in 1892, a fact that was oft contested on American soil well into the twentieth century.

Colonialism is always an expansionist enterprise. Not only in that it seeks to impose on as much ground as possible, taking over lands in the name of the Crown or Christ or King Cotton, but also in that its effects take over our minds and the way we see and think about the world around us.

Speaking from what he believed to be the point of view of colonial administrators, Jean-Paul Sartre writes about colonized peoples in the preface of Frantz Fanon’s revolutionary text The Wretched of the Earth: “They will not get anywhere; so, let us perpetuate their discomfort, nothing will come of it but talk.” And “It’s enough to hold the carrot in front of their noses, they’ll gallop all right.” It is easy for colonizers to see people as idiots and beasts. Criminal is not a far cry from either.

By 1865, nearly four million former slaves had become refugees on the very same lands they were once forced to work. In January of that year, white Union General William T. Sherman went to twenty Black leaders of the Savannah, Georgia, community seeking advice over this problem. The Black leaders there recognized a mutual relationship between land and liberty, and told Sherman that if they were to have one, they needed the other. Days later he penned a radical plan for land redistribution that explicitly called for the settlement of Black families on confiscated Confederate property. It’s where the “forty acres” of “forty acres and a mule” comes from. “The negro is free and must be dealt with as such,” Sherman’s order said.

At 7:36 p.m. on September 16, 2016, Tulsa police received a 9-1-1 call about an abandoned vehicle in the middle of a road about seven miles away from what was once known as Black Wall Street.

When activist Steven Biko wrote in 1978, “the biggest mistake the black world ever made was to assume that whoever opposed apartheid was an ally,” he meant that opponents to specific instances of Black oppression are not necessarily pro Black liberation. This was true in 1865 as well. President Andrew Johnson overturned Sherman’s order at the end of the Civil War, nixed after less than a year. He returned most of the land to the white former slave owners to whom it had originally belonged.

It took almost no time to realize that the thirteenth amendment wouldn’t do much in the way of changing America’s view of the former slaves, who had little choice other than to again work for and be indebted to the same people who still saw them as property. It’s my guess that any faith those freed Black people had in northern whites looking at them any differently than those who originally enslaved them was, at that point, lost.

Still, in the years following Reconstruction, America’s Black population went north and west, looking for better opportunities and better ways of life. They were also looking for refuge from the terror in their so-called freedom. White Americans of that era were well known for resorting to horrible violence against us—dragging, hanging, shooting, and burning; touching, prying, tying up, and raping; cutting off ears, toes, genitals, and strips of flesh—without fear of prosecution. Sometimes, they said, they were “defending” white women’s honor. “Assailant of Mrs. Cranford May Be Brought to Palmetto and Burned at the Stake.” Sometimes they were just having fun. It is documented that an eight-year-old Black child was lynched in South Carolina for “nothing.”

In 1908, O.W. Gurley, whose parents were once slaves, built the first building along a muddy Oklahoma trail—the future Black Wall Street of America—in what would become the thriving all-Black Tulsa community called Greenwood. Gurley’s vision was not obscured by the colonial lens through which most Americans saw the world. He could see Black people as human—who embodied potential—and so could see Greenwood before it ever existed.

Just over a decade later, Gurley’s muddy trail was a bustling street lined with all kinds of businesses. Greenwood had become a thriving Black metropolis, home to 10,000 of Tulsa’s Black residents. There were Black doctors, Black lawyers, Black schools and teachers, Black owned clothing stores and sweet shops, a Black mechanic. I read somewhere that at one point, six Black Greenwood residents owned their own airplanes.

When I first heard about the Black Oklahoman who was recently gunned down by a white cop in the middle of the street, I wondered what had originally brought his family to the state. Did he have ties to Greenwood?

*

At 7:36 p.m. on September 16, 2016, Tulsa police received a 9-1-1 call about an abandoned vehicle in the middle of a road about seven miles away from what was once known as Black Wall Street. "Somebody left their vehicle running in the middle of the street with the doors wide open,” a woman told the dispatcher over the phone. The vehicle belonged to Terence Crutcher, a forty-year-old Black man from Tulsa who presumably had car trouble.

Officer Betty Shelby was the first to arrive. At some point, a police helicopter showed up.

I wonder if my grandfather ever considered that his contributions to aeronautics could make more efficient the surveillance and oppression of his own people.

Shelby—white, female, the only woman on the scene—shot and killed Crutcher that fall evening, just minutes after first encountering him on the street. Thirty seconds after backup arrived. He was walking away from her—approaching his SUV, hands up—when she discharged the fatal shot. She says now—despite not responding to a call about an armed person, despite Crutcher not being a suspect in any sense—that she thought he had a gun, or perhaps that he was going to retrieve one from his vehicle. Maybe she was scared. She claims she was momentarily deaf when she pulled the trigger; this is why she didn’t hear the sirens of the approaching backup, which could have assuaged her fears. Her vision, however, was intact the whole time.

“Looks like a bad dude,” says one of the white officers in the helicopter, moments before Crutcher is killed. Maybe this made him feel good and whole. He could only see Crutcher from a distance. Always at a distance. We are always defined from a distance. The killer, Shelby, was looking at a person from whom she was too distanced to comprehend as he truly was. A person she would rather shoot and kill than learn the truth of.

There’s video of Betty Shelby killing Terence Crutcher, recorded by both a squad car’s dashcam and the police helicopter. I didn’t watch the footage when it was first released; watching Black death weighs heavily on those with Black bodies. But when I finally did, I watched closely. A second viewing. A third. I could not, for the life of me, see what that officer saw—but I know the trope of the Black person as “bad dude” is ingrained in our collective American unconscious. It’s an image that is burned into our minds with each reading of To Kill a Mockingbird or any Thomas Dixon, Jr. novel, every viewing of the nightly news or The Wire or Cops.

In defense of their beloved, Terence Crutcher’s family pushed back against the assertion that he was a “bad dude.” They spoke with the media, telling stories that they hoped would humanize him. “He was my compassionate son,” his mother told us. “Terence said he was going to make it big as a gospel singer,” his father shared. We have heard others bear witness in this way, testifying to an unacknowledged humanity. I read that Trayvon Martin’s first visit to New York was only two summers before he was killed. I learned he wanted to work in aviation—“fly or fix planes.”

I ache when I think about how none of that matters. We are always refuting the notion that people will see what they want to see.

*

“If we all worked on the assumption that what is accepted as true is really true, there would be little hope of advance,” writes Orville Wright in 1908, five years after he had gone on the world’s first successful engine-powered airplane flight. In those decades following the Civil War, it was generally accepted as true that Black men were violent rapists. Famous suffragist Rebecca Latimer Felton captured this mood perfectly when she cried, “If it takes a lynching to protect woman’s dearest possession from drunken, ravening human beasts, then I say lynch a thousand a week if it becomes necessary!”

Felton wasn't alone in her willingness to sacrifice Black lives. White Oklahomans lynched forty Black people between 1882 and 1968. Of all those lynchings, there is one that stands out most in my mind: The attempted lynching of Dick Rowland in 1921.

It began as many lynchings did in that time, with an identification of a Black man as “bad dude” by way of an accusation of rape: On May 30, Rowland, a nineteen-year-old Greenwood man, was arrested on assault charges that were later dismissed—and highly suspect from the start. He was accused of assaulting Sarah Page, a white Tulsan woman. According to all historical documents, the assault never occurred, but Rowland was promptly taken into custody nonetheless.

This was a common occurrence; the white imagination has always regarded Black men as sexual predators, and the accusation of rape was used to justify innumerable lynchings. (Many other lynchings did not involve Black men charged with rape, but were aimed at Black women and children as punishment for petty “crimes.”)

“The frequency of these lynchings calls attention to the frequency of the crimes which causes lynching,” a Memphis newspaper proclaimed. “The ‘Southern Barbarism’ which deserves the serious attention of all people North and South, is the barbarism which preys on weak and defenseless women.” However, “the actual danger of the Southern white woman being violated by the negro has always been comparatively small,” writes white historian Wilbur Cash. “Much less, for instance, than the chance that she would be struck by lightning.”

Rowland’s arrest was just what white Tulsans, resentful of Greenwood’s success and economic stability, had been waiting for. Quite a few people—lay Tulsans and historians alike—believe the events that unfolded next to have been a planned conspiracy.

On May 31, a number of white Tulsans formed a mob in the hopes of lynching the accused. A group of Greenwood residents, however, was determined not to let the lynching happen. Following a confrontation at the jailhouse, civil officials deputized the white Tulsans and provided them with guns and ammunition, which they used to invade the Black community. Twenty-four hours later, Greenwood was burned to the ground. Three hundred Black residents were killed. Over 1,000 homes—and virtually every other structure in Greenwood—were destroyed; Tulsa’s white residents, ever the colonial conquerors, looted what was left.

It didn’t stop with death and destruction. In the hours and days following the massacre, all of Greenwood’s surviving residents were arrested—removed to holding centers in other parts of the city, only to be released into a white person’s care.

“The aeroplanes continued to watch over the fleeing people like great birds of prey watching for a victim,” writes Mary E. Jones Parrish, recounting the horrors of that day. White men shot at Greenwood residents—black men, women, and children; all “bad dudes”—and dropped bombs on them from planes. Airplanes were used by the police for “reconnaissance.”

Planes were used by photographers and sightseers in the aftermath, too, although most of us are not privy to their accounts. This is the American history, not as rare as you would like to think, that isn’t taught in schools. This is the American history hidden in attics and hope chests, next to Confederate uniforms and the Halloween pictures showing your uncle in blackface.

“It is not right, my fellow countrymen, you who know very well all the crimes committed in our name,” Sartre writes, again in the preface to Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, now from his own perspective. “It’s not at all right that you do not breathe a word about them to anyone, not even to your own soul, for fear of having to stand in judgment of yourself.”

Not one white person, then or now, has been prosecuted or punished for the massacre.

Betty Shelby was out on bond twenty-three minutes after being arrested for killing Terence Crutcher.

*

Two years after Greenwood, another Black community, Florida’s Rosewood, was destroyed by a white mob looking to avenge another assault that never actually happened. The attack left all of Rosewood’s residents homeless, many hiding out in the swamps for days until they were evacuated. Emblematic of what is worst about America, lynchings were common during that period of our history, but so was the destruction of Black communities. It wasn’t enough to take Black lives, Black space, Black land. Black potential had to be taken, too. The white mobs said they were protecting white women, that their bloodthirsty behavior was in the name of law and order. “I think it was more of a passkey,” my dad said to me once. “They can do whatever they want to us if they just say they’re scared.”

Still, we rise. In the wake of all this destruction, a joyous event occurred: My granddad was born, just two months after Rosewood.

Imagine the minds who gave us the ability to fly, all vision and measurements and math. Flight comes from the minds of people who aren’t afraid to plummet. The kind of people who can dream what they cannot see and then, almost miraculously, conjure it into existence. We are taught that those are people like the Wright brothers. But they are also people like my grandfather.