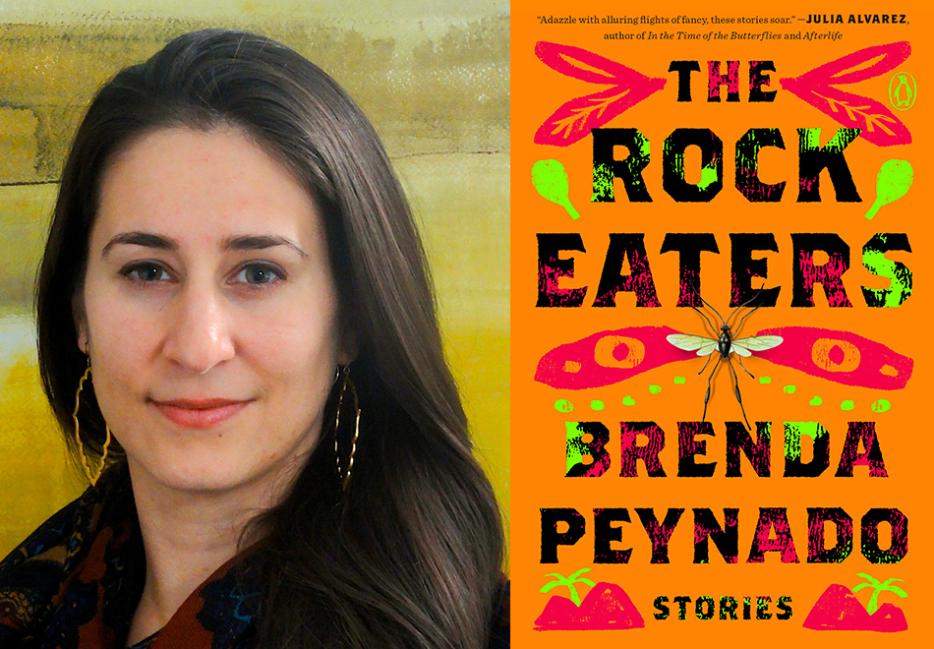

In the opening story of The Rock Eaters (Penguin Books), Brenda Peynado’s debut collection, a child and her family perform oblations to the angels that live on their suburban rooftops. These benevolent beings don’t pay much attention: “They chewed their cud from the grasses and bugs they scavenged during the night and then shat runny white on our roofs, the shingles looking iced with snow despite the Florida heat.” They sound more like pigeons than god-adjacent figures, don’t they? The story, incidentally, is titled “Thoughts and Prayers,” and concerns a school shooting.

Peynado’s stories are full of such clever twists on the relationship between the sacred and the mundane, the familiar and the alien. While a lesser writer might let the conceit of a story dominate it, Peynado never does; there is a deep emotional core to all the stories, and often a political one as well. In “The Stones of Sorrow Lake,” a young woman travels with her beloved to his hometown, a place that doesn’t let people go once they’ve experienced some kind of trauma there; in another story, “The Whitest Girl,” a group of adolescent Latinas experiment with the power of othering and exoticizing, tools learned at the hands of their own oppressors; a third, “The Touches,” an eerily prescient story, deals with touch hunger and isolation in a future ravaged with disease, where the outside world is so deadly that people live alone in small, secluded rooms, their material needs taken care of by robots. The Rock Eaters asks big, complicated questions about the nature of love, alienation, marginalization, and power, but it doesn’t attempt to give concrete answers. After all, these are questions human beings have been asking for as long as we’ve existed and written things down.

I spoke to Brenda Peynado over Zoom just after the book’s publication. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Ilana Masad: People in the contemporary literary sphere like to say that it's difficult or impossible to publish a short story collection before a novel. But you did just that! Would you tell me a little bit about your road to publication?

Brenda Peynado: Yeah! So each of these stories was published previously, before being collected in a book, except for the first one, “Thoughts and Prayers,” which I wrote after the book had been sold. So the road to publication started with just publishing those first short stories. A lot of them have been years in the making. I had published maybe 40 or 50 short stories before selling the collection.

I think one of the things that's so hard about publishing short story collections is just that every MFA has one; if you've written 15 stories, suddenly you have something that you can consider a collection.

I think my road came from not publishing [in book form] the first 16 stories [I had]. They didn't all fit together, and my writing changed a lot over the course of a decade, from very realist stories into more fabulist, going back to the genre that I loved writing. I kept getting better as a writer with every year. So a lot of my early stories ended up not making it to this collection.

I did think that I was going to have to sell [the collection] with a novel, but I have an amazing editor who believed so much in the short stories that she didn't want to buy the short story collection as a freebie for the novel. She believed in it as its own book and really loved the stories.

I’m so glad; you’re such a good short story writer. How did you decide, from those 40 or 50 stories that you've published, which ones would come into this collection and how you would organize them?

The organization was [in service of] making it feel like you were prepared for what was coming next. So even if one of the stories was realist and the next one was science fiction, [I was] trying to get it so that one would pick up a thread that a previous story left off.

One example of this might be “The Touches,” along with a story like “The Dreamers,” and a story like “The Drownings,” and how they’re about human connection and trying to understand each other, and about romantic love, but they're also wildly different. And seeing them spread out over the collection—as opposed to clumping them all together—has the effect of creating a good thread.

The only ones that I felt strongly about, in terms of order, were [the first and last stories.] I knew that “Thoughts and Prayers” had to be first, and I knew that “The Radioactives” had to be last. I really want to make people cry, and I want to show the brutalness of humanity, but I also wanted to show tenderness and I wanted to end the book on a feeling of hope: that these superheroes [in “The Radioactives”] were coming to save us, in a way. That despite all of the ill, despite everything that had happened to them, they were still coming and they were going to save everyone.

I wanted “Thoughts and Prayers” to be first because it picks up all of the themes of the other stories. You know, it's got the angels, so it sort of prepares you for the genre bending that happens; it has this Latina girl [narrator] and it deals with girlhood; and [the narrator] is sort of considering what forms love can take and what is worth protecting: Is love worth protecting? How do you protect it? How do you love someone, even if they're the unlucky family across the street or your mother wielding gun? I think that story sort of encapsulated everything that I was trying to do in the collection in a fun way.

Something that appears in quite a few of the stories is how many different viewpoints on how to deal with a problem can exist side by side in one family, or in one community, and how people can love each other despite those incredibly different ways of approaching a problem. What does fiction allow you to explore about the complexity of how people love each other?

I was probably never going to be a good essayist because I don't have answers. I only have lots and lots of questions about the world. One of the things that fiction can do so well is not give you any answers and just pile on the complexity of a question, which is where I love to linger. I think this probably says a lot about me—I'm so bewildered at how there can be such brutality and harm and sorrow in a world where there's also such love and joy. And it's not that they exist in different pockets, they're sort of mutual and flitting back and forth between each other.

There's so much harm that can come from love. I just think about people with guns and how they're not shooting someone necessarily because they think, I'm going to get this gun and I'm going to go out and harm people. I mean, there are some people that do that, but there's a lot of people who are like, I'm going to get this gun, ’cause I'm going to protect the people that I love. It comes from love, even if it's flawed love. Or, you know, how much harm we can do in relationships, trying to love each other and how flawed and desperate that love is at the same time as it can be beautiful and joyful.

I feel like fiction—even in political stories—always has to remember the individual and remember that all of these brutal things are coming from such complicated desires. And a lot of those desires are the same ones that we have even when we don't agree with where someone is coming from. So in my fiction, I really don't want to give people easy answers; I just want to show people how complicated all of this is. I think that's what can really make people cry at stories: how inevitable the sorrow is, as well as the beauty that comes along the way.

The stories in The Rock Eaters span various genres, from straight up realism, to fabulism, to sci-fi, to magical realism. Do you know, from the start, if a story is going to go toward one genre or another? Do you discover as you write? How does genre play into your process?

I sort of think genreless in that I don't necessarily have them in separate boxes. I usually start a story based on an image and that image can end up in any genre. Each writes its way into the story. I began “The Kite Maker” just with an image of these aliens flying a kite. Then I thought, Why would this be meaningful to them, and how would that be heartbreaking? Oh, they've lost their planet and this kite is representative of that lost planet. And then I was like, Okay, who's watching them? Who would that [act of] watching them break? Oh, somebody who feels incredibly guilty at the harm that she's caused these people, and the weight of that. So I went from the image to like, Okay, whose heart is this going to break? And whose heart is that going to break? The story came from there.

Sometimes the stories come in layers. With “Thoughts and Prayers,” I knew I wanted angels on the roofs and that school shooting. Part of that was because I think about school shootings a lot as a teacher. Every year we get thethis-is-how-you-avoid-dying-from-a-student-who’s-become-violent seminars, where they were giving us tips and tricks to stay alive, like take off your belt and you can tie the doorknobs together!

That’s so bleak.

Right? So I had school shootings on the brain. I was raised very Catholic and my mother prays for a lot of people and it just kept feeling so insufficient to me. Like, Mom, I appreciate that you're praying, but also, is it that you think that not enough people have prayed for the people that died? Do you think that anyone who’s saved, it's because enough people prayed for them or prayed hard enough? What is it that you think that prayer is doing in the world?

So I wanted to have these angels as an embodiment of this prayer, and people [pray to them] because they feel like they have to or because they believe it, but also, they can't quite figure out what it's enacting in the world. From there I was like, Okay, I know there's a school shooting. I know there are these angels. I know there are these two girls that are best friends.

Another story, “The Stones of Sorrow Lake,” was a really realist story when I wrote it the first eight times, from scratch. It wasn't until the stones [became] the embodiment of what I wanted to talk about—a legacy of sorrows in this town's history—that the story ended up working, and finally I was able to write about what I wanted to write about.

Girlhood is a feature of many of the stories here; many of the protagonists are tweens or teens. What is it about that time that feels so rich to you as a writer?

I have been mourning my age lately, and part of that is how much I feel is lost. There's our aging bodies, but also how many possibilities are lost to us. When I was a kid, I thought I could be a super-secret spy, learn eight languages, have five different jobs, be an artist and a writer and an activist—all at the same time. I think there are some people who are able to do that, but I think for most of us, as we get older, the things that we can imagine ourselves doing start to narrow.

What I love about that time period [in girlhood] is just how many possibilities are open to us and yet how bewildering we find the ways to get there. I think what I love to write lingers in that stage of bewilderment and possibility and wonder, and that's the attitude that I like to bring to everything.

I also love how complicated girl relationships are, with frenemy-ships where you both understand each other and love each other to death, but you're also competing at the same time in this very fraught way.

Another thing that I noticed come up in multiple stories is the use of a plural first-person narrator, this collective “we.” What about this narration style calls to you, and how is it useful to you as a writer?

I really like writing in first person plural. Part of that is because when I have something that is too complicated for me to stare at head on with just one character, the “we” narration allows me to sort of layer on all of these complexities, whereas if I had had one character, I would have had to sort of stick with what they thought about the situation. So in “The Whitest Girl,” there’s the intersectionality of race and the way that [the Latina girl narrators are] thinking about getting back at what has gotten them, but also the ways that they could band together or not. It's hard to think about something that works on groups without speaking as a group, but I was also really interested in the ways that the group frays at the edges. In a story like “The Drownings,” [which deals with] death and risk, and [asks] what risks do we take, I wanted the story to feel like a dream, and I think the “we” narration gave it that sort of singsong, incantatory [feeling], almost like a group chanting.

I have to ask about “The Touches,” which was first published on Tor.com in 2019, well before the terribly, eerily, awfully relevant year we've just gone through. Did you think about it at all when the pandemic started and social distancing became a thing and touch hunger became something that people were suddenly talking about? Was it a weird life-imitating-art thing for you?

Yeah, it was really uncanny. I had written that at a time when I was interested in investigating loneliness and trying to connect with people. I had just moved to a new city and was bemoaning a loss of connection that I had before when I was in graduate school. That story came from a place of feeling isolated and wanting desperately to connect with people and not knowing how to do it. [I was just] imagining this world where we were all forced into that [isolation], and [touch] was forbidden to us. So of course, when the pandemic started, it became super relevant.

I think at the time, [when I wrote the story] there weren’t all of these political ramifications of will you mask or won’t you mask? Will you quarantine or won’t you quarantine? So I was able to look at it in a very isolated way, just assuming everyone is on the same page and somehow the governments of the world all got us to the place where we were quarantining. Then what would the world look like? And what would you do to transgress those boundaries? Whereas I think had I written it in the [COVID-19] pandemic, there would have been so many politics around those choices that I would not have been able to write the same story.

The weirdest part too, is—so I had virtual reality [in the story] and I had my main character electing for a baby. And the two things that happened during the pandemic were, first, last summer I got an Oculus Quest and spent a lot of time in VR. I went to a Metallica concert in VR, and you could actually see people headbanging. You didn't need to see their facial expressions; you were at a Metallica concert. And I also went to a jellyfish viewing at an aquarium in VR and there were a lot of people talking politics, and you could jump seats to talk to different people. So it was really interesting to be in VR, in quarantine, at a time when so much was happening and people were protesting. And second, out of all that and my feeling of isolation, [I turned] to my partner, like, you know what, let's start a family. Who does that? That's a bewildering choice to make considering all of that. But for whatever reason it felt right.

I noticed a lot of casual bisexuality in the book, by which I mean that it's not the topic of any story, it’s just allowed and there. How did you allow that in and let it stand without comment?

I think it is a privilege of bisexuality that you don't have to be out. People know you as someone who's dated men—if you're a woman—and you can casually mention that you have dated women before or relationships you've had, but strangely it's not a thing that necessarily needs to be announced until the moment at which you need it to be known.

My characters are also living in worlds where no one calls them on it. In the first story, “Thoughts and Prayers,” the mother does sort of comment on what she considers to be an inappropriate relationship between the two girls but she does it silently because it's something that she doesn't want to speak about, that she doesn't want to say out loud. I think that probably goes a lot more into the mentality of the “don't ask, don't tell” aspect of that privilege. But later stories are relying on leaps of imagination—I mean, in a world where people don't sleep, can’t we also have polyamory and bisexuality as something that is a matter of course and that nobody has to question? I think part of it is a hopefulness.