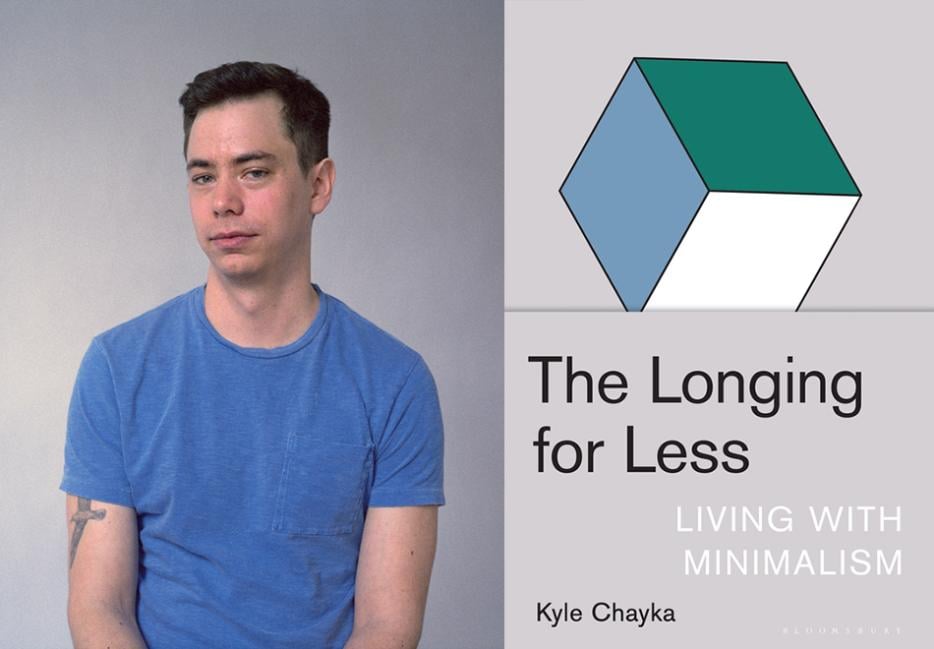

There’s a moment in Kyle Chayka’s The Longing for Less (Bloomsbury USA) when it feels as if the entire book is about to fall apart. Chayka, an established cultural critic for The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, The Nation and more, makes the incongruous observation that writing about minimalism is anathema because words crowd the stark beauty of a blank page, filling it with clutter. Indeed, there’s something unnerving about the impulse to decipher the meaning of minimalism, and the cognitive dissonance that comes with that acknowledgment elicits the power of a sucker punch.

The term minimalism has become modern gospel, shorthand for a self-congratulatory lifestyle that eschews the accumulation of material goods and casts all nonessentials as sheer frivolity. One needs only to glimpse at Kim Kardashian’s tchotchke-less, concrete home to understand that minimalism has become one of the most important—and loaded—cultural signifiers of our time. Chayka demonstrates that the basic tenets of minimalism have been conveniently repackaged multiple times throughout history, beginning with the Stoic philosophers of Ancient Greece, shifting to the transcendental self-sufficiency of Henry David Thoreau, and later, the “voluntary simplicity” adopted by people who shopped from the Whole Earth catalog in the 1970s.

The Longing for Less is a powerful meditation on the origins of minimalism, its recent commodification, and how it all went awry. Chayka explores famous minimalist cultural artifacts like Philip Johnson’s boastfully austere Glass House, Donald Judd’s sterile cubes, and John Cage’s brilliant musical troll, 4’33, to craft his argument that minimalism has the power to be far less dour than our current cultural understanding allows.

Chayka speaks in a sort of surfer-dude drawl, punctuated by plenty of “yeahs” and “totallys.” We spoke about minimalism as an inherent judgment, the aesthetics of community, and why he’s hesitant to identify as a minimalist himself.

Isabel Slone: Throughout the book, there are snippets of your own interest in minimalism: a wardrobe filled with grey clothing and a relatively empty Brooklyn apartment save for your roommate’s stuff. How would you describe your own personal relationship with minimalism?

Kyle Chayka: I started paying attention in 2015-2016, when I kept seeing the word minimalism pop up all over the place, used to describe the interior of a bar or a restaurant or a hotel. People were also talking about how they were living a lifestyle that didn’t put much stock into material possessions. And I had been looking a lot at this magazine, called Kinfolk, which ushered in this hipster-minimalist aesthetic of Spartan living. Around that time, minimalism was everywhere, but then I remembered that Agnes Martin and Donald Judd were part of an art movement in the 1960s called minimalism, and the work they made seemed to have little connection to what people were talking about as minimalism today. So I got interested in that disconnect between how people were using the word and the origins of the word.

You clearly appreciate the aesthetics of minimalism, but you stop short of calling yourself a minimalist. Why is that?

The aesthetic of minimalism has always really appealed to me; bare empty rooms, the art gallery vibe. But the label of minimalism that emerged over the past 5-10 years actually doesn’t have that much to do with the ideas behind minimalism and minimalist art that attracted me. The thing that makes me hesitant is that minimalism as a concept has been super commodified, as we’ve seen with Marie Kondo selling crystals and tuning forks on her website. Minimalism has become a brand that I don’t think has much in common with the original meaning of the term. I wrote the book in some ways to follow that trail and see what it could mean in the future.

I’m curious about how minimalism came to be associated with affluence. It used to be that owning a lot of material objects telegraphed wealth, but now it seems to be the other way around. How did we get to that point?

Right now, minimalism is this commandment to consume fewer, better things. But aesthetics are always evolving and each era and generation has a different idea of what luxury means. In the 1940s and ’50s, post-WWII, the aesthetic of success and luxury in America was material accumulation. It was a house in the suburbs, a fancy car. But at the same time, artists and writers were rebelling against that, especially in New York. Artists started colonizing the factory neighbourhood of SoHo and moving into these giant lofts. Then over the following decades, that kind of industrial austerity became a luxury aesthetic on its own. From the 1980s to the 2000s, fashion brands adopted the lifestyle of the SoHo loft artist as a marker of cool, which they branded and marketed to us as a quote-unquote authentic way of living. Now every new condo building is a loft.

You brought up fashion, so I wanted to take your temperature on something. The rise of minimalism coincides with the fashion industry’s widespread embrace of down-market clothing; designer sweatpants have become more covetable than a bespoke suit. Do you see these two phenomena as related?

Totally. The promise of minimalism as a consumer idea is that you can buy one perfect, multipurpose item. That’s not going to be a finicky fashion thing, like a couture dress or a tailored suit. It’s going to be the kind of hard-wearing, sturdy basics everyone is gravitating towards. It’s sort of funny, "basic" is another word for minimalism, in some ways. What Everlane and Uniqlo are selling, for example, is essentially affordable, minimalist clothing that will not make you stand out and not make you look bad. It’s middle-of-the-road optimization of fashion.

There’s this conception of minimalism, exemplified by Philip Johnson’s Glass House, as an implicit boast…

I would say it’s explicit.

Okay, an explicit boast that seems to pass judgment on anyone who doesn’t live by its tenets. Is this sense of being judged by minimalism a legitimate reaction or just a perceived slight?

I think it’s a totally valid reaction. The sense I always got was that minimalism can be a form of control, and it’s really easy to feel not included, or that your messy humanity is not accommodated by the style. I remember being in this hotel in Texas that was all cement: walls, ceiling, floor. It looked very cool but it was an inhuman space. It felt oppressive, like it was not conducive to living things. On the other hand, we can compare Philip Johnson’s Glass House to Donald Judd’s loft as an example of minimalism as a lack of control, where you can let anything into your space and not have to force the style. Minimalism doesn’t have to be homogenous. Hopefully I sketch out an idea of minimalism that’s not so judgmental and not so controlling.

What I perceived the conclusion of the book to be is that unhappiness and disappointment lies at the root of our cultural obsession with minimalism and if people learned to be more accepting of their lives, they wouldn’t feel the need to exert control over minute things. Is the galaxy brain meme version of minimalism just…not giving a fuck?

I think my sense of minimalism is much closer to not giving a fuck than trying to make a perfect space or trying to find the perfect object. I mean, I’m still very pretentious. I love finding great stuff. But this idea that you can buy a perfect set of furniture and thus control your life is very problematic. The people in the book I like the most are the ones who give less of a fuck about following an orthodox set of rules.

Like the Eames. Is there anyone right now whose DGAF minimalism you think will be remembered fondly by history?

Steve Jobs was a huge design influence on everyone’s lives. The iPhone sort of set the expectation for this wealthy, glossy, minimalist aesthetic of technology. But the Eames would have been so against iPhones. They would not like what is going on, I feel.

You write that minimalism is simply a natural reaction to living through the brash excess of the early 2000s. Do you think the aesthetic pendulum with shift soon and we will begin to crave noise and clutter once more?

You have to separate the trendy style of minimalism from the ideas that define it. I think the fad will inevitably fade pretty soon. We’re already seeing people turning against the super austere style. But to me, the idea of considered living and developing your own sense of taste and living in a sustainable way is so much more important. I think it will keep being a concern, especially in the next few decades considering climate change and the possible apocalypse and the total upheaval of our lives is a looming threat. Minimalism is a survival strategy, I think. And right now feels like a moment to survive, rather than accumulate more crap.

You position minimalism as the aesthetics of individualism, yet the culture feels like it’s starting to shift away from the individual in favour of community. Is there an aesthetic for community?

As a fan of minimalism, I hope that minimalism could be an aesthetic for community as well. You see the hope of design for community in Bauhaus, or even the Eames ideal of making the best thing for the least money for the most people. I think minimalism’s aesthetic is, to use a tech phrase, minimum viable style. You can make it cheaply, you can adopt the style easily and use whatever is around you. So I think minimalism could be the aesthetic of impromptu communities or industrial reuse.

There’s a phrase you use in the book I found irresistible: “luxurious minimalism.” These two concepts that should theoretically oppose each other actually work really well together in practice. Can you expand a bit on what you mean by luxurious minimalism?

That’s the paradox of the book, I suppose. How did minimalism become luxurious? Speaking to the context of the Japan chapter, whether the phrase appears, the people in Heian Japan around 1000 AD lived these lives of extreme luxury. They had tons of servants and giant mansions and were surrounded by material goods and they just seemed to have appreciated it all so much. Despite their surroundings, their quality of living was actually not that high. The structures they lived in were super drafty, they were not as technologically advanced as China or Korea, at that point they had kind of cut themselves off from the world. So in the absence of other influences, they were driven to appreciate, say, the blooming of a single flower, or the intricate changing of the seasons, or the smell of one stick of incense. Shonagon, the author of The Pillow Book, was obsessively recording the super mundane details of the world. I think that’s kind of a luxury in itself, to be able to notice everything so closely and observe what’s around you. That’s the luxury of minimalism to me. Not wanting to accumulate more stuff, but instead wanting to have the luxury of attention and an appreciation for what’s already there. We don’t have that enough.

That’s a lovely thought.