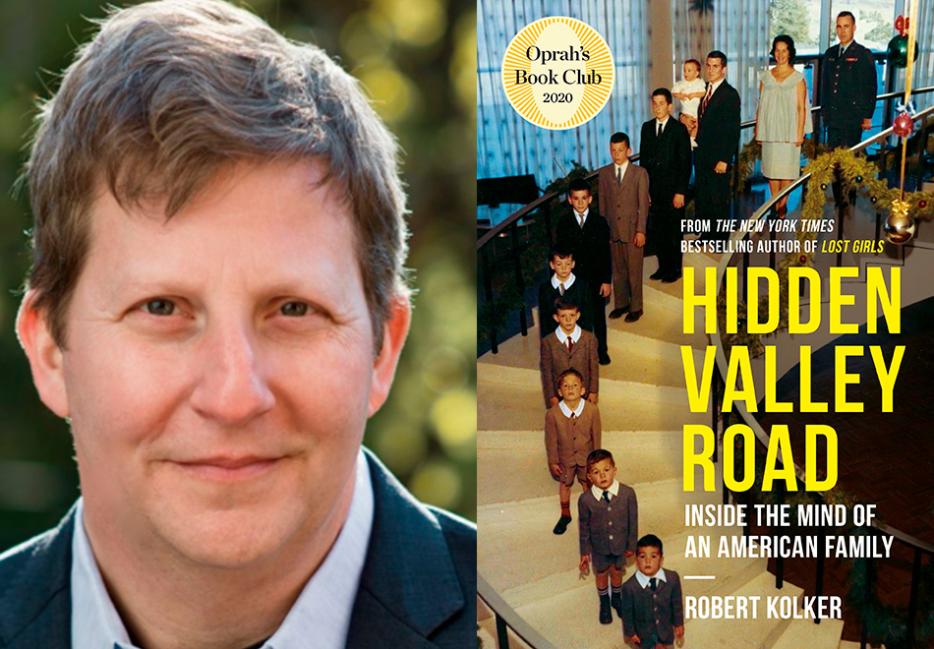

Robert Kolker's first book, Lost Girls, is a heartbreaking and methodical account of women whose bodies were found on an isolated Long Island beach. It's a true-crime book, but one where the violence is not the point. There is a tremendous amount of heart in Kolker’s writing and reporting: he makes you care about the people whose lives are destroyed by violence.

In his new book, Hidden Valley Road: Inside the Mind of an American Family (Random House Canada), Kolker takes on a difficult subject and once again infuses it with heart and analyzes it with his characteristic perspicuity. The book revolves around the Galvin family of Colorado. Don Galvin, a rising star in the Air Force, and his wife, Mimi, a dedicated homemaker, had twelve children starting in 1945. Then, tragedy began to dismember the Galvin family, and six of the Galvins's sons were diagnosed with schizophrenia. The compassion Kolker brought to Lost Girls is also evident here, now an Oprah's Book Club pick, which is a penetrating story about how mental illness affects families.

Lisa Levy: The book is fantastic. What's happening with the book is fantastic. You must be over the moon.

Robert Kolker: I am, it's really mind-blowing, and especially great for the family, who put themselves on the line by going public this way. To get this kind of response is a wonderful thing for them as well, so I'm really happy for them.

How many of the kids are still around?

There are nine living siblings, three of whom are mentally ill. The other six are all involved in the book.

This wasn’t my first question but it seems natural to ask now. How did you convince them to do the book?

Well, the sisters were ready. They had been talking for decades about the best way to let the world know about their family, and they were also curious about any sort of scientific contributions the family could make. Finally, they decided to ask an outsider to come in and report on it independently. By the time they called me, they were energized and excited to be talking to me, and so there was this funny disconnect in that first conversation where they were talking about these horrible, horrible things that had happened to them and to their entire family over many, many decades and yet, they were so pleased to be talking about it at all. It just seemed curious to me. I was like, wow this is such a sad story and they are so happy to be talking about it.

You must have had that feeling a little bit with Lost Girls. Some of those families also seemed like they were on a crusade to get the story out.

That’s true. In Lost Girls, the families had a lot of fatigue from media attention by the time I was working on the book, and they did not necessarily see the value in a book. It was me saying it's worth it for the world to get to know your lost loved ones in a way that's more detailed and more realistic than what's out there already. It took a lot of pushing on my part and a great leap of faith by all of them. But in this case, the family was really ready from the very beginning and it was I who had to try to get my arms around the story and understand exactly what it was and how to tell it.

Well, let's talk about that a little bit. How did you meet them? How did you come to the story?

Lindsey, the youngest of the 12 siblings, went to high school with an old friend of mine who edited me at New York Magazine for 10 years. His name is Jon Gluck. And among many other stories we worked on together, we worked on the story that was expanded into Lost Girls, so he understood that I had a lot of experience writing about people in crisis, people facing adversity, people who had been through difficult situations. So, when Lindsey contacted him in 2015, she said that she and her sister had been talking for years about this, that now they thought it best to ask a journalist to work independently and take the story wherever it went. He thought of me and thought I would be a good match, and so he connected us by email. I took it from there.

Were you looking for another book or did this come along and you said, I have to do this?

I was very much looking for another book, but I also was very happily fully employed at the time at Bloomberg Businessweek as an investigative reporter. When I first got to know the Galvins my thought was, well, obviously, I wanted to write more books one day. Nothing happens overnight with books, so why not take this very, very slowly, get on the phone with everybody in the family over a number of weeks just to make sure that people were as enthusiastic about this as the two sisters were, because there are medical privacy laws in America and all it would take is one family member to stand up and push back and suddenly it would be less feasible.

It only takes one person to yell HIPPA [the primary medical privacy act in the US].

Exactly, right. I was very skeptical, but at the same time, I knew that it's a slow-burner, these book projects. So why not give it a shot? I was amazed and pleased to see how enthusiastic they were about talking to me. Others were ready to do it because they respected the sisters’ wishes and believe the sisters had really been through some of the worst of it and deserved to have their story told. And Mimi was on board, which was a bigger deal than I realized at the time. She was very pleased to be speaking with me, but I learned later that she was not always interested in a book or public attention, and so it was a relatively new thing for her to be into it, so it was good timing, that way too.

Well, she's a fascinating character. Over the course of the book, she's more and more willing to talk to people and accept help. At first, she definitely feels like a very closed ranks, family business kind of person, but as things sort of disintegrate, she realizes that she needs help.

Exactly. The best way I think I can put it is that the children's view of both their parents changed over time and so does the book’s. Readers may feel one way about Mimi in part one and start to feel a different way about her in part two.

She reminded me of my grandmother and that generation. Something like mental illness is not something you were going to talk to even your friends about.

She reminded me of my grandmother too, in that she always had a sunny disposition and was not necessarily interested in talking about unpleasant subjects and had become very good at deflecting unpleasant subjects. That much they shared for sure.

How long did you work on the book?

About two and a half years, but you could add an additional year of really going full-time on conversations and meetings with the Galvins before I came up with the book proposal. By the time I started I was really up and running because I had a whole year of prep work beforehand.

Was this easier because you had done Lost Girls and you were used to this sort of blanket reporting, where you had to keep a lot of narratives in your head at the same time?

It was a little easier. I definitely still had huge dead ends and weird conundrums I had to deal with where I would sit there and go, now what? Or, how do I handle this? But the big way that it was different is my attitude. Lost Girls was my first book, so I had all kinds of stress and impostor syndrome and doubt and self-doubt. And because of that I kept a lot of the work to myself and didn't really share bits and pieces of it with friends. I just tried to keep a happy face on while, privately, I was really sweating it. I decided this time that I was going to take really active steps to have a life while I worked on it. I said to myself that if I'm going to write more books in my career, they can't all be these soul-crushing seismic difficult events. It should be a little bit more like a career and less like a stunt.

Jumping from one trauma into another.

Right. I created some balance. I shared large parts of the book with lots of friends, and I took a cooking class and because I was at home all the time, it was the right time for our family to get a dog. So we got a dog, and that was life changing.

Every writer should have a dog, I think.

Exactly. I had never been a dog owner before, so it was all new to me. But just to be able to have a well-rounded life while working on it was important to me. I also should say that there is more hope in this story than there was in Lost Girls, even though it's a terribly dreadful story for the family. There are little bits of hope. I kind of held on to that too as I was working on it.

What were the main things you had to learn so that you could report the book?

The book was a really good mix for me of work, the sort of work I had done before, which is talking to vulnerable people about difficult situations they faced, and something entirely new, which was the science of schizophrenia. One reason why I got into this line of work was to learn new things. It was intimidating, but I was really, really excited to have the chance to learn something from scratch, and I really was starting at zero. And I had lots of incorrect notions about it. The biggest misconception I had was that I thought that the drugs that people were using to treat schizophrenia every day were as miraculous as the drugs that treat depression or bipolar disorder. I learned that they really weren't, that they were certainly helping in some ways, but they weren't really working toward a cure and that was a big eye opener for me. Then just being able to look at the science of schizophrenia as a narrative, to see how it changed and evolved in the different debates over the years was really, really a terrific process for me. I really learned a lot.

Brain research in particular is fascinating because it's so primitive. They are constantly finding out new things by accident. That’s the way a lot of drugs were developed: it turned out that the drug didn't work for one thing but it worked pretty well for something else.

It's like throwing darts blindly and then if you're lucky, something happens that you aren't expecting. It certainly is like that for a lot of mental illness drugs as well. It was something that was developed for something else.

Lost Girls was about abuse and trauma and the things that we take away from our families that are negative. So even though the family is, I think, generally trying to help the brothers who are ill, there's still a stigma attached to what's happening to them.

The subject of abuse and childhood trauma is an interesting one for me because I really don't wake up in the morning thinking, “What next story about trauma and abuse should I tell?” It isn't the thing that is driving it for me. And yet, these two books both have it, have a lot of it. Perhaps it's simply because I'm drawn to stories about people facing adversity. It's certainly not out of anything in my life personally that I'm resolving.

More families are like that than not.

Certainly, that's true. The things I really like to write about best are intimate personal stories. I'm not a pundit and while I've done investigative reporting, it's usually because I'm motivated by the people in it. I'm not an essayist or ideas writer, and I don't do first-person stuff. I really want to do narratives about people so the people are going to be going through something tough and this is as tough as it gets.

Yeah, when I was comparing your two books, that's where I landed. I landed on trauma, I landed on marginalized people. The mentally ill are marginalized, much in the way that the women of Lost Girls were, some of whom were probably also mentally ill.

I am purely operating out of an established playbook by idols of mine. Alex Kotlowitz or Katherine Boo or Adrian Nicole LeBlanc is amazing. Or David Simon, using these amazing nonfiction narratives that are about marginalized people or people who we might overlook even if they aren't officially marginalized. I'm trying to do what they're doing.

Well, you're doing what they're doing. What's interesting is that the writers you just mentioned all have written really incredible books that somehow tell a universal story, even though they’re about marginalized people.

And I hope to do that too, for sure. To me, that's one of the things that journalism can do. It can make the world smaller, and help you relate to people who you've never thought you'd have anything in common with. These are some of the amazing things that good non-fiction can do.

One of the other similarities I felt in these stories is a lot of them break down to be stories about mothering. I think we both blame and venerate mothers. When people have troubled lives we still look at mothers and think, well, what's going on there?

I was alarmed by that with this book. I was worried because, god knows there are enough family stories out there, fiction and non-fiction, where the mother really takes it on the chin. And I was not interested in that trope. In conversations with all the children, I learned that they were re-evaluating both parents as life went on, and so fixated on that and decided to make that a big part of the story.

Well, it's hard because Don sort of drops out of the story because he becomes ill.

That's exactly right. By the time it came to make some really serious decisions about his sons, he was no longer the decision maker. [Mimi] has sole power. Once one son died in 1973, there was no way she was going to be overruled on any decision. It would have been an interesting and different story if there were two parents there continuing to work on this issue, but it just wasn't that way.

Why do you think they had so many children?

It was unusual for them and their families. There were other large families in Colorado Springs at the time but the Galvins were the first to do it. Not all the Galvins have large families. So even their own families were wondering why this was happening. I think I arrived at two ways of looking at it. One is that the Gavins like having a life of distinction. Don liked being the guy who flew the falcons and they liked being known as this large family, this model family. Mimi, who had given up the life she had wanted, could build a life that was more interesting to her and made her feel special. I think she also was filling a hole in her life. I think she had some losses that she was trying to gloss over, like the loss of her father who left the family in scandal and the loss of her husband who became more of an absentee parent and the loss of the future she thought she could have. And so here was a way to create a lot of new company for herself to stave off abandonment. I think it worked for her in a lot of ways, and not just because she wanted people to look up to [them] as a model family.

The Oprah’s Book Club people are starting to read the book and some of the commenters there are interested in the idea that she was competing with Don, which isn't something I really explored, but it's an interesting idea. She's this very intelligent woman who is going through what a lot of women in that generation are going through. She's relegated to a homemaker role when she could have gone to college. Her husband is this big shot who's really accomplishing everything professionally and she's at his mercy in terms of what kind of money they make, where they live, everything that happens. And so maybe she is doing what she can do to accomplish something too.

It’s hard not to think about how, in the beginning, he is the star and as the book goes on, she takes the reins. But where he gets to be this fun, larger than life public figure, she's just trying to keep it together privately.

Yes, and she's adjacent to his public life. She's on his arm at these events and stuff, but it's not really her life, it's his life.

Do you think in a different era she would have made different choices? Did her daughters talk about that at all?

Yes, I think as kids, they grew up saying, Why on earth is my mother neglecting me and choosing the six sons over me? Why did she put me in harm's way? The two sisters now look at her and think, What were her choices? Now that they are both married and have children of their own, and have been able to make lots of decisions about their lives, they realize that Mimi’s choices were limited, her tools were limited, the understanding of the illness is limited. She may have made some colossal errors of judgment but she also was operating with real limitations.

At this point, the sisters are filling the role that she had to and making decisions about their brothers’ care, I would imagine.

Yes, and we see two different ways of dealing with that in the two sisters because they are not alike. Lindsay is aggressively trying to do what her mother did in terms of caring for the brothers and there's a price for that, which is that she has a certain amount of mania about it and ends up having some difficulties with the people around her because of it. Margaret goes the other direction where she feels that it's a bottomless pit dealing with the family issues, and so she creates some boundaries. But there's a price for that as well because then others begin to resent her.

I would think the resentment started when [Margaret] went away. This is actually something else I think will be interesting with the book club readers: what do you make of a mother who sends a daughter to a family that they're not super close to? It's very unusual but actually a very shrewd thing for her to do.

I think there's so many ways of looking at that. In the beginning, I looked at it as something out of Charles Dickens, like this mysterious wealthy benefactor pulling one of the children out and it just seemed so larger than life. But as you said, there's the resentment of the people left behind. Then there's Margaret’s own feelings of alienation and abandonment, being sent away when it was really the brothers who she thought maybe ought to be sent away. She feels penalized and deprived of her family for reasons that she doesn't understand. There's the culture clash of her being in this wealthy family, and then looking back at her family. The sisters’ lives are different from then on because they aren't together, but they are both cursed with a certain hypervigilance, like they're walking on egg shells, because they're ready for the worst to happen at any time, and that plays into every decision they each make.

Still?

Still, absolutely. If you were to meet Lindsey or Margaret today on a ski slope or at the Whole Foods they would seem like anyone else. Perfectly congenial, nice, intelligent, friendly people. But in their emotional lives and the legacy of their childhood, there's a certain walking on egg shells feeling that they both have and will continue to deal with. And I'm sure the brothers feel that way too. I mean, as kids, they all woke up every day wondering if they were going to go insane like their brothers. I don't think you ever really get away from that.

What do you want from your next book? You reported these two very intense, very moving stories, which are also very bleak in some ways. But I don't imagine you’re going to turn it all around and do Mary Poppins. But you're obviously drawn to a certain kind of story. How would you define that? What kind of stories do you like to tell?

I love non-fiction narratives, and I prefer to tell stories about ordinary people who are going through something extraordinary so that readers can sort of follow along and put themselves in their shoes. And as an added bonus, it would be nice also to be able to learn about a completely unfamiliar world while experiencing this narrative in the way that one does when reading Katherine Boo.

I'm happy to write another true crime book, but it doesn't have to be true crime. I'd be happy to write another book about mental illness. Really, the priority would be human stories that lift a veil on something that you may not understand immediately.

Do you think you'll continue to write about families or is that sort of incidental?

I think it's incidental. If there were an amazing story about someone where the family didn't come into it, I wouldn't shy away from it, but I will say that for years and years and years, I wanted to find some way to report on a family that had a estrangement because I am interested in the subject of family estrangement. If you talk to my [former] co-workers at New York Magazine, my close friends there from years ago, they would all say, oh yes, Bob said that he wanted to do that a long time ago. How amazing [is it that] this presented that chance?

Do you have another book in mind or you just sort of like sitting back and taking all of this in?

I have nothing right now. I have a couple of ideas that might end up being shorter things, but I really don't know. No big promising book project at the moment. And that's a mixed blessing. On the one hand, I think it would be nice to have the promise of something new to work on, while promoting something that exists. But on the other hand, in the middle of a global pandemic, it's probably nice that I'm not feeling overworked. I have one job right now and that's to support this book and also keep the family feeling okay during the quarantine.