In April of 2003, two editors from the Italian magazine Indice forwarded five interview questions to Elena Ferrante by way of her publisher with a request that she participate in a section of the magazine they’d titled “Unsuccessful Writing.” Two months later, Ferrante sent back what amounted to 70 pages of text and the polite but unyielding statement that she “had no desire to make a shorter, publishable version.” Ferrante’s response to the magazine’s interview request is now the sixteenth chapter of her latest book, Frantumaglia.

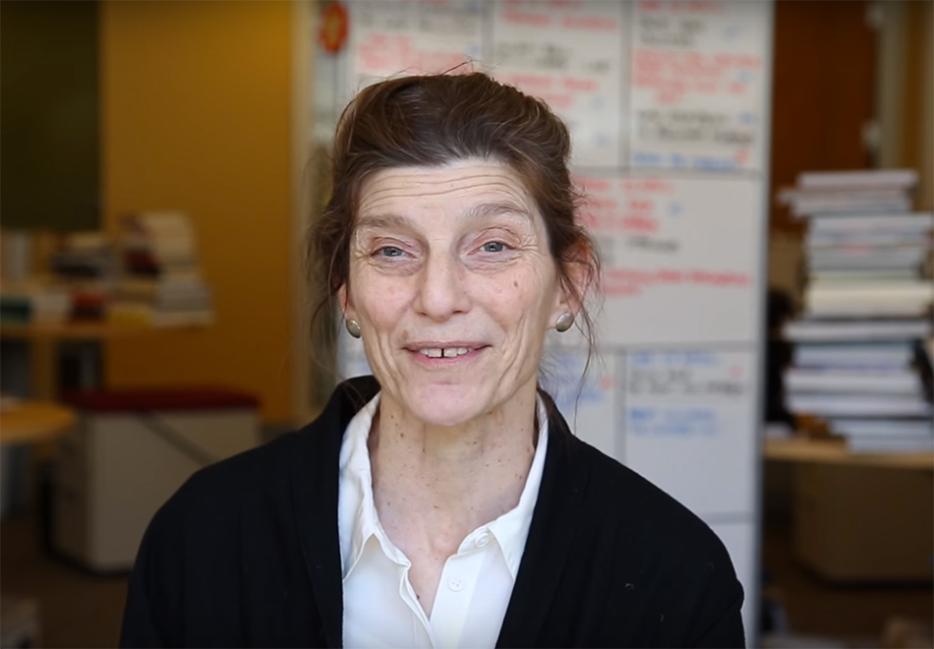

Ann Goldstein, who announced her retirement as head of The New Yorker copy department this week, began translating Ferrante’s work in 2004 with The Days of Abandonment. Since then, Goldstein has translated all of Ferrante’s books, including Frantumaglia, an incidental memoir comprising letters, interviews, and ephemera from the past 25 years of her life.

In that sixteenth chapter, Ferrante teases out the meaning of the word that gives the book its name. “My mother left me a word in her dialect that she used to describe how she felt when she was racked by contradictory sensations that were tearing her apart. She said that inside her she had a frantumaglia, a jumble of fragments.”

Goldstein, too, deals with a kind of linguistic frantumaglia, reconciling the meanings and sensations of one language within the form of another. Instead of tearing her apart, translation tends to bring the jumble of fragments together. Language is the fabric of Ferrante’s uncompromising genius, through which she shows her intellectual and emotional endurance.

As head of the copy department at The New Yorker, Goldstein’s daily work was about maintaining the integrity of the magazine’s sentences. Translations of Ferrante’s Italian are a reorganization of that editing instinct, solidifying something that’s already there and making it legible to the English-speaking world.

The temptation is to ask Goldstein to speak for Ferrante, whose anonymity creates a portrait by omission. Instead, I asked about her work both in partnership with, and lateral to, the specter of her brilliant friend.

Naomi Skwarna: You mentioned in a recent interview with Melinda Harvey that you’re “only the creator of [Ferrante’s] world in language.” I wonder if you could tell me what your goals are; what defines your ear and hand as a translator?

Ann Goldstein: Philosophically, I would say that my goal is to make the best English version, that is to say, to render the voice of the Italian writer as well as I can. At The New Yorker we talk about how people always complain that everything sounds the same—“They make everything sound the same,” which is really not true! I think that our goal is always to make every writer sound as good as he or she can sound. There's a similar goal in translation. It's about making a person more herself. Or as much him or herself as possible in the other language.

Is there a process of adaptation at all?

I don't know if I would call it adaptation, but you're always making a choice that might not be the one somebody else would make. You're choosing from a range of meanings. When Ferrante uses a word in Italian, it has a certain resonance in that language. You're probably not going to find a word in English that has the same resonance, but you have to find the one that you think is the most important.

I don't know if this is a fair analogy, but it brings to mind the interpretation of a piece of music—different instruments, different players.

It is. There's an essay by an Italian writer called Cesare Garboli where he talks about the translator as an actor, a performer, and no one's ever going to perform the same way.

Early in Frantumaglia, Ferrante writes “…when one makes a creative work, one is inhabited by others—in some measure becomes another.” Does translation follow this rule as well? You’ve mentioned previously that you don't embody Ferrante in the process of translation, but is it absorbing?

Totally. Ferrante especially, partly because there was so much of it! 1,800 pages, years of my life. I was living with those characters. I remember when I finished the third [Neapolitan] book, I felt that something was wrong, something was missing from my life. And I realized it was the voices of these characters that had been in my head for so long. You're reading word-for-word, sentence-by-sentence.

In the Neapolitan Quartet, there are numerous mentions of the dialect spoken in the neighborhood. How did you approach those references to dialect, even if the dialect itself wasn’t present in Ferrante’s writing?

I didn't consciously do anything, but as a translator following the lead of the author, I think it might've come out a certain way. I've heard Italians say that the language is slightly different, that you can hear echoes of the dialect in the language when Ferrante says it. Not of the words, but the sound or the feeling of it.

What drew you to Italian translation?

It was accidental. We had been having Italian classes at The New Yorker office when the artist Saul Steinberg sent the then-editor Robert Gottlieb a book by Aldo Buzzi in Italian. [Gottlieb] said "what am I supposed to do with this?" He gave the book to me and said "can you read this and tell me something nice I can say to Saul?" So I started reading the book and I was very taken with it, and I just decided to try and translate it. So I did, and then it got published. It was really completely serendipitous. I thought translating would be a way of studying the Italian language in a much more intimate way.

What was it about Italian that caught your imagination?

Dante. I wanted to read Dante in Italian. I'd had this ambition for many years and finally it came true. I had read it in translation, the Latin. That old Italian has many similarities. It wasn't a question of understanding it differently—although probably I did. I don't think I saw it or understood it differently, but I did understand the language differently, because I was reading it just in Italian with Italian notes.

Was there a different emotional experience?

You read a book at a different age, it's a different experience. Dante in college—in certain ways expresses all the seeking and yearning, the emotional turmoil of college. But, Dante has a lot to say when you're older, too.

Does The New Yorker still offer language lessons to their staff?

No company has anything like that anymore. It was amazing! They would pay for any kind of class that theoretically improved your work. Language classes are obvious, but anything that made you a better reader or a better worker, in a way. Those were the days.

You're known for your translations of Elena Ferrante, but you've also translated Primo Levi's collected works, Jhumpa Lahiri, and others. Within the different texts you've translated, did you find any particularly challenging?

I recently translated a Pasolini novel called Street Kids and that was really hard and really illuminating. It does have dialect in it, Roman dialect, which is maybe not as different a language as Neapolitan from Italian, but it was difficult and different. I don't think there's a good way to translate dialect, I don't think there's a good way to find an equivalent. Some people suggested using a Brooklyn accent, but it would just sound silly, because you know you're not in Brooklyn—you're in Rome. I ended up making the dialect parts more slang-y, or less grammatical than the other parts.

Frantumaglia features a lot of professional, but still intimate, correspondence. Did you find that different than translating Ferrante's fiction?

Well, there's no dialogue, so yes. Her fiction isn't easy to interpret, but in some of the interviews—the correspondence not so much—sometimes she's saying really complicated things, and it's not always easy to tell what she means. It was difficult in a different way. Not in terms of the sentences, but in terms of the concepts, and therefore being able to translate them correctly. There were a couple of interviews that were particularly difficult. One place that I think was hard, in a different way from the novels, is the discussion of transcendence [in Chapter 17 with Nicola Lagoia]. Granted, I think the question was not easy to translate either.

Did you get a different sense of her as a person?

I would say that I got a more specific sense of the author that I feel I'm familiar with through the novels. I had a sense of the person writing those novels, and the Frantumaglia pieces seemed like another aspect of the same person. A person you know is very intelligent, very sharp, sometimes sort of crusty and impatient. Not necessarily nice. But also: incredibly generous, taking seriously all these questions and answering them with great gravity and thoughtfulness.

Generosity is something I thought of as well—her willingness to engage so fully with people who were more-or-less strangers. I particularly loved anytime I saw that a long and carefully composed letter hadn't been sent.

Yes! (Laughing.)

Has your work as a translator of Italian affected you as a copy editor, or as reader of English work?

Studying any language, understanding the structure of another language is extremely helpful in understanding how English works. I had already studied Latin and French, so I had a sense of structure and the way other languages work. But Italian is different. I think it refines your sense of English.