Frogs lie unseen until you happen to walk past them, at which point they jump in large, startling numbers, and cease being not seen. A character in Jennifer Croft’s The Extinction of Irena Rey uses this frog fact to comment on literary translators: they are “invisible other than in motion,” she says. It’s a fitting idea to bring up in a novel that’s teeming with translators—translators who are very much hopping around, present, at the forefront, definitely not not-seen.

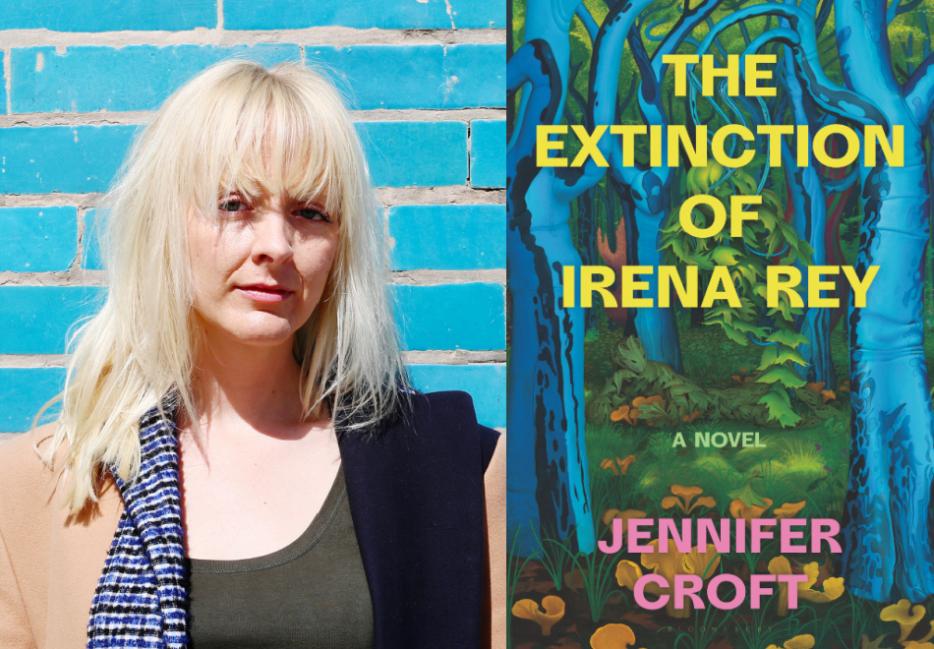

The Extinction of Irena Rey (Bloomsbury) is Croft’s first novel, following her 2019 memoir, Homesick. She is also a celebrated translator of Polish and Argentine Spanish, a Man Booker International Prize winner for her translation of Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights, and a lauded advocate of translators’ right to be credited on book covers.

In The Extinction of Irena Rey, eight translators gather in the home of a world-famous Polish writer, Irena Rey—a big kind of writer whose books inspire eco-activism, death threats, film adaptations, and Nobel Prizes—to translate her newest novel. The translators have always gathered in this way, for a ritualistic “summit” at their beloved author’s home, which sits at the foot of the primeval Białowieża Forest, a UNESCO World Heritage site straddling the Poland-Belarus border. The translators work around a table with Rey presiding. The ceremony has overtones of a cult.

But this time, Rey is unlike her usual self. Something’s off. She soon disappears, and the translators are left to fend for themselves in her home, a modern-day House of Usher. Indeed, Gothic undercurrents abound: paranoid clue searching, oddities, seclusion and isolation, mysterious illnesses, and all kinds of violence are experienced by the group as they fumble, reach dead ends, and try to make sense of their host’s strange departure.

Croft’s novel is in large part about translation—one could even call it an allegory of translation. The novel is structured in a series of frames: within Croft’s The Extinction of Irena Rey is another novel, also titled The Extinction of Irena Rey, authored by Rey’s Spanish-language translator, Emi. This, in turn, is translated for us by Rey’s English-language translator, Alexis. From her perch on the metafictional scaffolding, Alexis provides occasional commentary in the form of footnotes, often attacking Emi’s literal approach to translation (or Emi in general) and advocating for her own more contextual translation style. Fans of Nabokov’s Pale Fire—another frame narrative with an intrusive footnoter—will appreciate the tension between the actual narrator, Emi, and the hijacker, Alexis. The resulting, often humorous, battle-of-narrators is a formal distraction of sorts—another layer in a carefully balanced work stacked with modes: Gothic mystery, picaresque adventure, psychological study of grief and loss, environmental fiction, a novel about novels. Emi likens translation to detective work, and we readers are called on to do this, too, as we wade through richly sedimented content. We tune in to a more curious, open, and alert state. We search and deduce. And we arrive at our own version of what happened to Irena Rey.

I have long admired Croft—a translator working with three languages that I grew up speaking. I’ve also long been captured by the magical Białowieża. It was a pleasure to talk with Croft and root around the highly unusual forest-green world of The Extinction of Irena Rey.

Marta Balcewicz: I’ll start with the end—in the acknowledgements to The Extinction of Irena Rey, you say that you started writing the novel in Białowieża Forest. The book is so suffused with magical, odd, unexpected, weird, perplexing, fun, terrifying, and hilarious events that occur to and are experienced by the group of translators—some of whom are also writers and poets. I can’t help but commit the sin of wanting to connect an author’s fiction to her biography and ask whether you, the author who also worked on her novel in the forest, experienced any magic and oddities, or maybe horrors, and how your experience in the woods influenced your choice to make Białowieża a central element of your novel?

Jennifer Croft: I’ve been to Białowieża a few times, the first time with my father in 2004, the most recent in 2021 as I was working on The Extinction, and I have always been deeply fascinated by the forest, which is just so unfathomably rich, so dense and so varied, unlike anywhere I’d ever been before. But where I had been before was a patch of land that included meadows, a lake, and a forest near where I grew up in Oklahoma—I spent part of every summer there, and in my childhood, that space, too, was suffused with magic.

One of the traditional stories of the summer camp was Jane Shaw Ward’s Tajar Tales, about a character who was “something like a tiger, and something like a jaguar, and something like a badger,” and who was always getting into trouble. Children had to be careful not to seek him out—although we were allowed to write him letters, which we deposited into the hollow of a particular tree—because “if you see him once, you would forget what he looked like, but if you should see him twice, you would forget to forget what he looked like, and that would be quite fatal.” I was always amused by that way of putting it, “forget to forget,” and I loved Tajar’s friends, like Madam Witch, who lived in a magic tree, and the Range Ranger, who “ranges the ranges in that region.” I think that is why I decided to include the ancient Slavic mythological figure Leshy, an embodiment of the forest and a trickster himself.

But also, this is a book about books, and especially about transforming books, which does feel like magic to me, even when I’m doing it. I think there’s something in the ceaseless transformations of the forest that coincides perfectly with the action of translation and that makes for a mood of magic and oddities, and maybe horrors, as you so beautifully put it in your question.

In one of her footnotes, Alexis gives props to Polish writer Witold Gombrowicz. One of my favourite books, his novella Cosmos, came to mind as I read Irena Rey—specifically, the way it functions as a kind of deconstructed detective novel. Like The Extinction of Irena Rey, Cosmos features guests staying at a country house in Poland, utterly obsessed with odd clues and discerning patterns and meaning around them.

Definitely Gombrowicz, a Polish writer who also lived in Argentina for twenty-three years, was a primary source of inspiration for this whole book. I love Cosmos, and I love Pornografia (maybe most of all his books), and I love his neo-Gothic, possibly satirical, pseudonymously published-in-serial-form novel The Possessed, which was recently retranslated by the masterful Antonia Lloyd-Jones. I take a lot of inspiration from Gombrowicz’s vision of self at odds with the other, and in particular with others as organized into units of family or nation, since when others unite it’s difficult for the self to resist them and remain a self. Then again, of course, there is no self, there isn’t really anything, and I also love how Gombrowicz turns that notion not into a motive for despair, but rather a reason to celebrate, as language disintegrates around us, and we are left with a kind of wild carnival of no-stakes pleasure-seeking.

Unlike in a more conventional, non-deconstructed detective novel, there is no final truth in Cosmos—nor, I would argue, in The Extinction of Irena Rey. What we’re left with instead is an organizing of the metaphysical illusions that have haunted the minds of the characters, in the same way that a dream makes cogent and organized something that is not, objectively speaking, resolution, finality, or truth. Could The Extinction of Irena Rey be described as a “deconstructed detective novel”?

In a way, if we believe our narrator, Emi, we do arrive at a kind of resolution at the end of The Extinction. It’s a vexing resolution, and one that raises a number of additional questions, but it’s a resolution all the same. Unfortunately, our translator, Alexis, tells us not to believe what Emi has told us, which means we can’t really be sure what happens between Irena Rey and her translators around the translation of her magnum opus, Grey Eminence.

That gets at something I feel about translation itself, which is that it’s a really intimate process that takes place between: between two readers and writers, between two languages, between two texts. All the action is in that third, middle text that’s never fully a text—the one that is partly in Polish and partly in English, with mistakes and questions and squiggly red lines all over it. Only a very active reading of the translation can come close to that kind of excitement. It’s like the difference between having an affair with someone and hearing about someone else’s affair. Why did the person having the affair have the affair? No one can know exactly, and maybe the person having the affair doesn’t even fully know, but they feel it on a visceral, instinctive, undeniable level. I wanted to create a situation in which we know something terribly exciting is happening between an author and her translators, but we can’t quite know what.

The themes of a natural order versus its disruption, or chaos, seem central in The Extinction of Irena Rey. Irena refers to the forest as a “network.” Her disappearance disrupts the translators’ natural system of working, and they themselves are likened to a fungal system. Irena’s subject is the current, or sixth, extinction—the first to be precipitated by humans, due to our hubristic disregard for the network. I was attuned to the ways in which the translators fractured their network—with infighting, personal interests, paranoia—and yet I ultimately saw them as mitigating this fracture, regrouping, the way nature often can. Reading the news, I learned that the parts of Białowieża damaged by the devastating, real-life 2017 deforestation—the basis for Irena’s crisis—showed signs of regeneration in subsequent years. Even the assignment of numbers to Earth’s extinctions has a grim hopefulness to it: sixth implies a seventh, which implies a post-sixth regeneration. Do you think of The Extinction of Irena Rey as carrying a message of hope, however indirect or unexpected a form this hope may take?

It’s really hard to wrestle with all the pain and suffering in the world, which is why I wrote this as a kind of literary sitcom about life, death and climate change, rather than an emotionally exhausting drama. I have to be hopeful about the Earth’s future, the future of animal welfare, and the future of humanity, and I imagine that comes through in the novel, with its emphasis on regrowth and transformation, as opposed to eradication, whatever the title might suggest.

Irena Rey, as conceived of in Emi’s novel, is a writer with significant pull: her works change the world in palpable ways. Irena’s novel about lichen is said to have led to the enactment of EU-wide environmental protection legislation—as well as threats of rape, death, and deportation, and nominations for every extant literary award. Irena’s task, says Emi, is “stitching up the world’s wounds with language”; and her new novel might “save the world.” When asked to name writers with these kinds of transformative agendas, many of us would think back to the nineteenth century, to Tolstoy and Dickens and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Do you think that this type of writer still exists today? Is Irena Rey possible in 2024? Is this vision of a world-changing author…extinct?

I definitely think Irena Rey is possible in 2024. I can think of lots of fiction writers in the twentieth century who changed the world in all kinds of different ways. Chinua Achebe, George Orwell, Joseph Heller, S.E. Hinton, Anthony Burgess, James Baldwin, Harper Lee, Margaret Wise Brown, Franz Kafka, Erich Maria Remarque, Marcel Proust, Arthur Koestler, Dr. Seuss, Sylvia Plath, John Steinbeck, Ursula Le Guin. More recently, Toni Morrison, Margaret Atwood, Barbara Kingsolver, even J.K. Rowling, who shaped the ethics of a generation. Memoirists, too: Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi helped the world come to terms with the Holocaust; Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn exposed the myriad cruelties of forced labour in the Soviet Union. Lots and lots of literary non-fiction has made huge impacts—too much to list here, so I will limit myself to just one: Rachel Carson massively increased environmental awareness in the US and elsewhere and offered activists clear and tangible goals.

I felt at times that The Extinction of Irena Rey was set up as an allegory of competing theories of translation. One translator, Alexis, translates the work of another, Emi—and each holds views on translation so diametrically opposed that this leads to an actual duel.

Yes, I’m so interested in aporia, and this seems to me to be a good one. Because what is translation? Is it making something new that stays the same? We know it isn’t just making something new, and we know it isn’t just keeping something the way it was because we suddenly have access to it in a way we did not before it was translated. So what is it? Is it reading? Is it writing? Is it both?!

Emi believes in literal translation—that the author’s words are sacred and must be preserved. Alexis has no compunction about removing entire scenes if she feels that doing so improves the work, even allowing personal ethics to dictate this choice. Tellingly, the duel produces no clear victor: both fire wide of the mark. I was left feeling that you likely see merits in both approaches to translation. Where does your own practice as a translator fall on this spectrum?

My own approach to translation depends so much on the particular book—not even the author, because every book is its own creature, and I try to provide it the personal attention it deserves. I definitely understand Emi’s attachment to preserving whatever she can from the original text, and to following the author as closely as possible. This is in general an understandable approach, and in her case, it has to do with her background and her personality, her need to have faith in someone else who knows what they’re doing, since she never really feels like she does. Alexis doesn’t question what she’s doing for the most part, she just gets to work, and she cares far less about the original text or the original author than she does about the target audience, what she thinks will work for them and make them enjoy the work she’s doing. This is also understandable: Why bother to translate something if no one is going to want to read it? As in, they will technically be able to now, but they’ll probably read something else instead anyway.

Which is where the duel comes in, and I am so interested in duels in general, as a unique form of violence that was absolutely rampant throughout the Western world until around World War I, though there have been resurgences. Duels between men are so well-represented in fiction even well beyond that period—for instance, there are four duels and would-be duels in Gombrowicz’s 1937 novel, Ferdydurke, as well as three in Trans-Atlantyk, the first of which is between a character named Gombrowicz and a character who bears a striking resemblance to Jorge Luis Borges, who in turn featured duels in the stories “The End,” “The Encounter,” “An Examination of the Work of Herbert Quain,” “The Story from Rosendo Suárez,” “The South,” “The Garden of Forking Paths,” “The Duel,” “The Other Duel,” “Death and the Compass,” “The Two Kings and The Two Labyrinths,” “The Theologians,” “The Widow Ching—Pirate,” “Monk Eastman, Purveyor of Iniquities,” and “Guayaquil.” But in all the duel fiction I read, from whatever time period, I never came across a duel between women. Women were sometimes involved in the duel as a kind of extension of the male combatant’s honour, but they never got to fight themselves. It was important to me to address that inexplicable (at least hopefully inexplicable by now!) absence.

I’ll end on a hopeful note. In the days I was reading The Extinction of Irena Rey, a new, left-leaning coalition government was elected in Poland and a new Minister of the Environment and Climate was appointed. The ministry published a news bulletin on January 8th, titled: “Government’s first step to protect precious forests.” There is talk of drafting a constitution of Białowieża. The rational part of me knows that the conjunction of Irena Rey’s publication and the shift in the nation’s politics is a coincidence. Still, it was like seeing your characters’ wildest aims miraculously accomplished, in real life, in real time. How do you think the translators would feel about this today?

Yes, this is all such fantastic news, and I do think this particular shift has to do with both writing (international and domestic)—meaning all the journalists who were able to spread the word about the destruction of 2017—and the commitment and daily labour of the residents of Białowieża—the scientists, the local politicians, the national park workers—who have been quietly performing acts of care on behalf of the forest for generations. I think my characters would just be keeping their fingers crossed for more shifts like this one, all over the world.