No feeling is quite as unbearable as shame, except perhaps shame mixed with desire. The two emotions seemingly oppose each other. Shame lives in the crouching darkness and holds all of the things we don’t want to look at, all of our youngest, smallest parts. Desire is big and direct and requires us to look at, name, and then draw close to what we want. To be reaching for something that one is also desperately trying to shrink away from, is one of the most confusing and painful of contradictions.

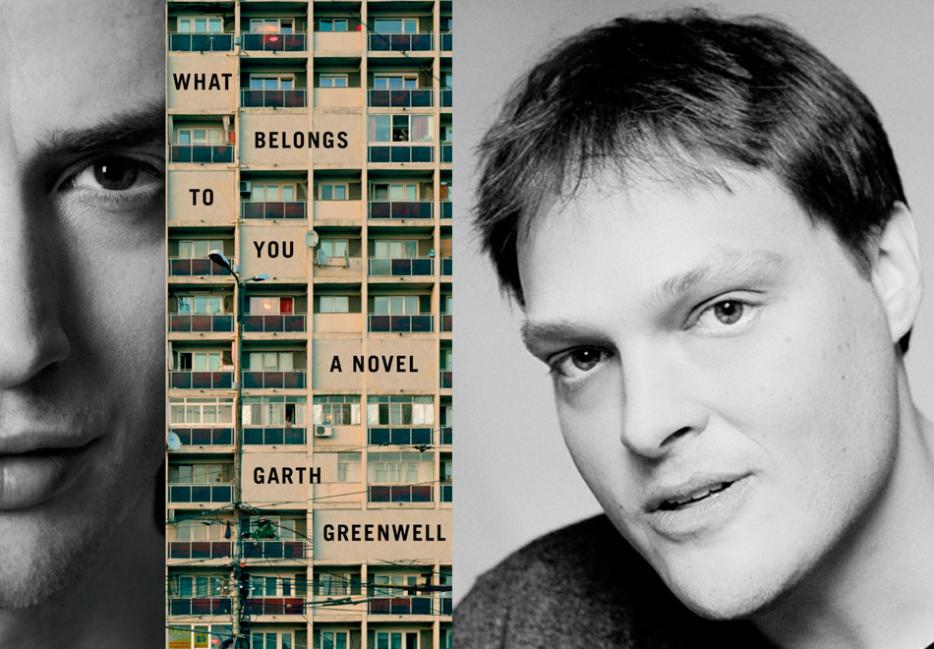

Garth Greenwell’s stunning debut novel, What Belongs to You, follows characters living inside this contradictory space of shrinking and opening, simultaneously ashamed and full of desire. Wanting with their eyes closed. The book concerns an American teaching in Bulgaria who meets a charismatic young hustler, Mitko, in a bathroom and pays him for sex. The relationship that grows out of that encounter is one that deeply unsettles the narrator and leads him back to his own fraught childhood in the South, one filled with rejection and danger.

It is a book that asks universal questions about love and grief and place, but also speaks to a queer notion of desire. Queer people are told from a young age that our desires are monstrous and so we associate desire with monstrosity, so much so that to leave that monstrosity behind might mean an extinguishing of desire and self altogether. But shame can only exist when it is not named, and What Belongs to You examines its characters’ secret pasts and humiliations with empathy and honesty. The book refuses to hide, and in so doing, transforms shame into something close to hope.

Originally an award-winning poet, Greenwell went on to earn his MFA in fiction from the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He spoke to me about the eroticism of language, the falseness of authenticity, and how important it is to be an idiot.

*

The book is divided into three sections. How did you come up with structure? Particularly the second section, which delves into the narrator’s past.

Garth Greenwell: I always tell people that if I died without trying to write a novel I would be really sad. In some way I tricked myself into writing a novel because I wasn’t convinced this was a novel until all three sections were written. I had never written fiction before I started writing Mitko [the novella that became What Belongs to You], and I had no idea what I was doing and what the shape of it was going to be and what genre it was going to be. When I finished Mitko, the first section, I really thought of it as its own thing, and I didn’t intend to write the second section of the book—but I just felt grabbed by this voice that I needed to follow. Everything about that second section was terrifying and disorienting. It wasn’t until I was deep into it that I realized what it was doing: trying to account for the choices the narrator had made in his adult life. On the way hand, the narrator claims to be constantly disclosing things in a sort of confessional way, but at the same time, he’s really guarded and doesn’t allow other people or himself close to his own feelings. So I realized that second section was exploring how this narrator became this weird mixture of disclosure and withholding.

Is Mitko the only character given a full name in the book?

He is.

It’s interesting, because naming is such a vulnerable, exposing act, and everyone else in the novel is protected by anonymity, including the narrator. What are your thoughts on that in terms of the narrator’s guardedness around himself and his past?

On the one hand, Mitko is the only named character because in some sense, I wanted a spotlight to be on him all the time. There is a spotlight on the narrator as well, and I think the narrator is equally but differently vulnerable. The question of naming is really central to trying to get a sense of what their relationship is and what it allows. At one point the narrator talks about calling Mitko “Mite,” which is like Mikey. It’s like a childhood nickname. He talks about how calling him Mite is a way of trying to conjure a particular version of Mitko, a particular tenderness. But, he says that when he’s calling Mitko by that name, he’s calling him by his “nighest name.” My editor flagged that and said, “This is weird, why are you using the word ‘nighest’?” I told him it was a quotation from Walt Whitman: When Whitman talks about the intimacy he can have with people with whom his connection is actually very tenuous, with whom his connection has to traverse all kinds of differences of class, nationality, labor, social position, he still asserts that they called him by his “nighest name.” So, the reason I said this has to stay in is because I think nighest [meaning nearly or almost] is the greatest affirmation of the greatest capaciousness possible for this relationship. The relationship between Mitko and the narrator begins as a transaction, and that really does affect and shape and form and deform the relationship. But one of the things I hope the book really asserts, in terms of questions of vulnerability of sex workers and of queer people in places like Bulgaria, is that the two people involved in that transaction both retain their humanness throughout this encounter. Which means there are moments between them that are full of possibility and in some ways those moments are captured by the fact that they have names for each other that no one else has.

This book made me think a lot about desire and love and the ways they interplay. What do you think the differences between love and desire are? Is it a difference of reciprocity and being seen by the other person? Or is it not that simple?

I think there’s love, there’s desire, and there’s sex. For the narrator and Mitko, the act of sex does not necessarily align with the experience of desire. The narrator speaks about his own past of cruising and indiscriminate sex—sex that was often not associated with desire. For the narrator, desire is inextricable from the experience of exclusion.

I was once asked how much this book was participating in a tradition of writing about sex workers, which is almost always a male character with a female prostitute, and my answer was, “I’m not sure it’s participating in those traditions at all.” One of the reasons is because, in those books, there is a presumption that the male desire carries along with it a kind of permission or entitlement. And the narrator’s desire in this book always carries with it a kind of prohibition. Which is why his first encounter with Mitko in the bathroom where he has an overwhelming desire for Mitko and then Mitko becomes available—the narrator’s experience is something close to wonder. The sense that desire and sex can align in this way at first seems like the opening of a door of incredible possibility. But of course, that possibility becomes really limited.

And the question of love: I think the narrator realizes the extent to which his experiences of love have always been partial. Early in the book he talks about love as looking. The idea that Iris Murdoch talks about—that love is an act of attention and by pouring out your attention onto an object you are committing a loving act. But in the last section of the book, the narrator realizes that’s not enough for love. He comes to understand it’s not just enough to look at someone—you have to look with them. You have to face what they face. You have to share that experience. And the narrator realizes he’s failed that in his life. And that’s the piece that can’t happen with Mitko, because there are all sorts of privileges that separate him, not just that the narrator has a place to sleep at night and food, but also that he has an American passport and he can leave Bulgaria and Mitko can’t.

There’s so much fear and shame wrapped up in the attraction between Mitko and the narrator, and it’s different kinds of shame because they are coming from such different places. But, do you think there is a queer desire that is free of fear of shame?

I think the question of what queer desire is and the forms it can take is changing so much. I hope gay kids coming of age today have a very different experience of desire from what I had as a kid in Kentucky growing up, which was one of prohibition.

Same.

And I think anyone of our generation, it’s hard to imagine that not being true. It is still the case that the lesson our culture tells queer people again and again is that our lives are not possible, especially to the extent that they don’t look like heterosexual lives. But we are in a moment that’s very different and that’s changing.

I went to Bulgaria in 2009, which was two years after Bulgaria joined the EU. When that happened, gay people got all sorts of rights and protections they hadn’t had before. In 2008 there was the first gay pride parade in Bulgaria, which was shut down by nationalists throwing Molotov cocktails. But each year that I was there the participation in the parade doubled, and there was an incredible movement in attitudes towards gay people.

But when I arrived, for all the unfamiliarness of Bulgaria, when I found a cruising place, it was the most bizarre feeling where I went from this upper world where I could barely speak the language and was totally lost, to this space where all of a sudden I was completely fluent. All of the codes were the same, I could communicate everything I wanted without needing language. And when I started to actually talk to the men I was meeting, I was surprised by how their sense of their sexuality and what it meant for the limited shape their lives could take, how much it felt like talking to men in the parks and bathrooms of Kentucky when I was 14, 15. I think that was the spark for the book: that I was back in an experience of queerness that felt deeply familiar to me.

Mitko is disempowered and stuck in so many ways, but the Internet is a space he can navigate freely and which connects him to other gay men. What do you think the role of the Internet and technology is in the creation or breakdown of identity, especially if you are creating an identity that might be false?

One of the things I think the Internet shines a light on is that all identities are hybrid and composite. And the very notion of an authentic or genuine identity becomes quickly untenable, especially if you are in a place like Bulgaria where historical change is happening so quickly and is so dramatically visible.

Another interviewer asked me if the EU-backed imposition of LGBT rights is in fact imposing a kind of Western value system on this place and destroying an authentic Slavik identity. While it’s problematic that LGBT rights have come as part of a package of capitalism and neoliberalism, I think there is no more dangerous concept than this idea of authenticity. My favorite place for this particular question is this metro stop in the center of Sofia in Bulgaria. As you stand on the street you can see from this stop an old Ottoman-era mosque, an Orthodox church that dates back to the 800s. You can see Soviet-era apartment lots, the EU-funded brand new metro station, and then, when you go down into the metro station, you can see in the corner some Roman ruins that they have preserved. So what would it mean to be authentic in Bulgaria in the first place? And I think the same is true of people—I think it’s a fundamental mistake to think there is an authentic core that then has these layers on top of it. I think, probably all we are is the layers.

What is your favorite thing about language?

Oh! The most important musical element of language to me is syntax and sentence structure, and I experience both of those in a very physical way. When I’m reading a sentence, I often find my body moving with it. Even though it’s really limited and we have this boring subject-verb object order that we almost always have to follow—the English language is so extraordinarily expansive. I love long sentences. There is something intensely erotic about the propulsiveness of a sentence.

Even asides and interruptions are erotic—it’s like a tease, not yet, not yet, and you’re being pushed and manipulated.

I love that, when it feels like the world has shifted under your feet! I also love when one language is imprinted by other languages. The history of literary innovation in English is the history of the collision of different languages. That’s true of the English Renaissance, which happened because Chaucer was reading Italian; and Romanticism, because they were reading German philosophers; Modernism, which happened because Elliot and Pound were reading the Troubadours and French poetry. Language is this rich composite thing that always does many things at once.

What’s the most frustrating or limiting thing about language?

I find myself pushing against structural elements that we use to organize and delimit thought. I think there is a real Strunk and Whiteification of English that happened in the 20th century, and that’s all about turning language into easily processed information. It’s about well-defined sentences and paragraphs, and those things to me work against the ecstatic potential of language. So for instance, the middle section of my novel is written all in one paragraph, which felt wonderful.

The thing I love and hate about language, and this also links back to the novel, is the ways that language can be both expressive and obfuscating. The narrator articulates this when he can only speak Bulgarian: He is struggling to make himself understood, but in some ways he is more honest because he can’t hide behind mastery. He realizes that in English, his mastery of the language, which he’s very proud of, is defense and armor and resistance of vulnerability.

What that narrator hates is what I love the most about learning foreign languages: I like being forced to be a child again in language. It is terrifying and humiliating, but also an experience that is full of wonder.

That’s how I feel about other art forms that don’t use language, or at least words—dance and painting and collage, anything where the ego I’ve built up for myself gets torn down.

Yes. So much of art is striving for mastery, but we have to find a way to stay in touch with that feeling of intense vulnerability. Because there’s all sorts of anarchic or ecstatic energy that is produced by just being an idiot. I have such a hair-trigger for humiliation. I think, for many queer people, so much of our life is an experience of humiliation that it’s really hard to welcome that kind of experience, but I think it’s the most important thing we can do as artists if we’re interested in growing and not just calcifying into a meaningless perfection.