Don Winslow hit a career peak, commercially and artistically, with 2015’s The Cartel. The Mexican drug wars, fueled by the American appetite for narcotics, with its city-and-village razing violence, killings both indiscriminate and calculated, radiates from its pages to a degree matched only by committed non-fiction accounts like Alfred Corchado’s Midnight in Mexico. Winslow has been careful to point to his debt to the journalists and on-the-ground writers in Mexico who made the profound research that went into The Cartel possible, even embedding heroic and extremely human journalists into the novel itself; Winslow didn’t risk death, while the men and women reporting cartel activities did.

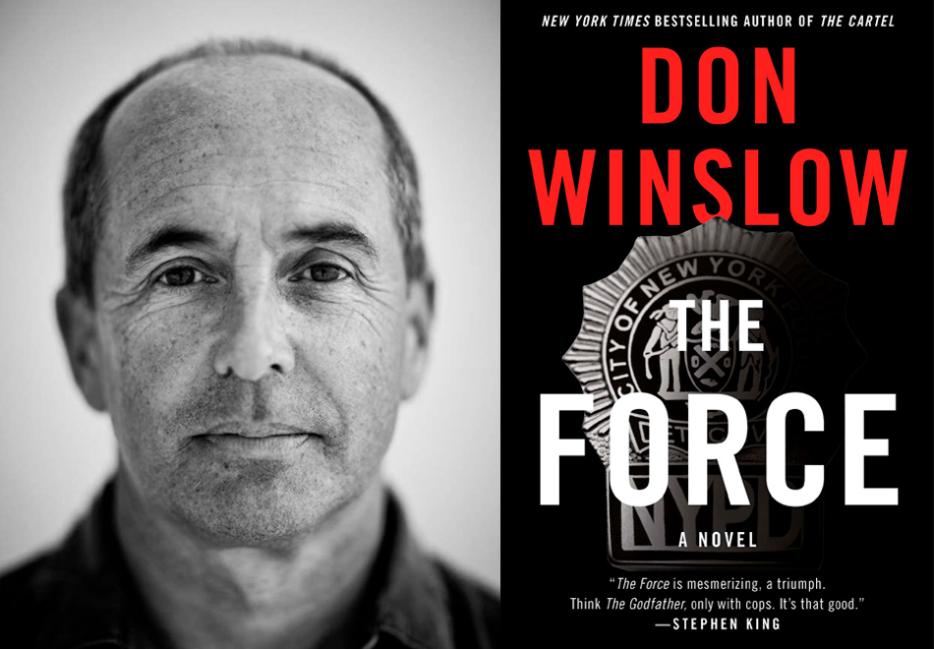

Accountability—more basically, more brutally, the idea of paying for what you write, do, steal, say—is a big part of Winslow’s work. The Force (HarperCollins), Winslow’s latest novel, asks big questions about who pays for police corruption, who pays for police violence against African-Americans in urban cities, who pays for the handshake favours and agreements that keep civic political and criminal organizations doing business as usual.

Born in New York and raised in Rhode Island, Winslow has spent much of his writing career in California, but the city where he was born, watched and read great crime thrillers, and finally became a private investigator, is where his The Force is set—where, maybe, it had to be set.

Talking about cops, talking about right-now, talking about who’s dying—a corrupt-cop book in 2017 has to be personal, as well as excessively well-researched, if it’s going to be good. For Winslow, talking policing and making it personal means New York City. For Denny Malone, the book’s complexly corrupt elite cop hero, Manhattan North is an identity and a territory he has to protect even as he continually exploits the job for every illegitimate dollar he can safely gather—until he comes to understand that no level of caution can keep him completely safe.

*

Naben Ruthnum: Why do you start The Force with Denny Malone in prison and then backtrack?

Don Winslow: That was a real internal debate for me. I argued with myself a lot about it; I originally didn’t write it that way. It’s the only book I’ve ever written with one person’s point of view. Even though it’s in the third person, it never leaves Malone through the whole book. I’ve never done a book like that before. It’s frankly easier to cut away—easier structurally—but I wanted the reader to be in this cage, in this dilemma, in this trap with Denny, right from moment one, and then just keep them there ’til the end.

I didn’t want to write a “what happens” book, I wanted to write a “how did it happen” book.

Denny talks about how being a cop where he works, in New York City, is part show-business—the mobsters in The Force grew up imitating movie gangsters, and the cop characters knowingly mock this. But who, onscreen, are your cops modeling themselves after? Who are they trying to be?

Like anybody else in the culture, we all grew up with police on TV. That cultural life-imitates-art/art-imitates-life keeps flipping back and forth. Those guys [in The Force], they watched Hill Street Blues, NYPD Blue, The Shield—those classic TV series. And in a sense, that informed who they are, formed their public persona.

Cops on the street definitely know that they have to give a performance. Sometimes it’s charm, sometimes it’s persuasion, sometimes it’s to calm people down—but other times it’s to jack people up, to intimidate. They definitely know that, to a certain extent, they’re actors.

Denny Malone talks about Serpico—Frank Serpico himself, that is. [Officer Serpico reported institution-wide police corruption in late 1960’s New York, his honesty making him a pariah in much of the NYPD.] But that got me thinking, Malone and the other cops on his task force have probably seen Serpico, Prince of the City, Q & A—these classic cop films about corruption. Beyond those cop shows, are these corruption-focused movies part of their makeup, too?

Absolutely. Those pieces that you mentioned were part of my inspiration for writing the book—I grew up on the movies you’re talking about. Part of what I was trying to do was write a story in that vein, but give it a contemporary setting and a contemporary feel. [Denny and the other cops] are very aware of those cultural icons—and they’re very aware of the history of police corruption in New York City.

I presume that going into a lot of the interviews you did with cops for research—both the cops who were your friends and the ones you were just interviewing—they knew that you were writing a book about quote-unquote dirty, “bad” cops. I say quote-unquote because the morals in this book, like your others, aren’t cut-and-dry. How did this knowledge of what you were going to be writing about affect what they were willing to tell you?

Well, that’s a very closed society. Know what I mean? Cops have a reflex which I absolutely understand, I can’t argue with it: to be defensive. You need to remember that that’s a world where information is currency. Whether it’s information they have about a case, about a suspect, about each other, about internal politics inside of a precinct house or inside the department, information is always currency. So, they have a reflexive habit of protecting. And then, when you start talking about things like corruption, that heightens the tension.

But like any relationship, I don’t care if it’s a source, or a friendship, or a marriage, or a parent-child relationship: there’s no substitute for time. I’m never going to start an interview saying, “Hey, whaddya think about police corruption?” That’s a bad idea. I use the same sort of interview technique that I used as an investigator. I try to ask as few questions as possible, and I try to start them out as broadly as possible.

I would typically, with someone I had recently met, say, “Tell me about being a cop.” When you start an interview that way, what you always get is what’s foremost on their minds. If you start an interview with your own questions, you’re already shaping the perception into something you already know.

You walk a bit of tightrope, then—because, as you said, they’re not forthcoming interview subjects. You’re asking these broad questions, then you need to encourage these cops to elaborate at the right moment.

I wouldn’t call it a tightrope. I’m not a journalist, I’m not doing an exposé, I’m not going to a grand jury. I’m a fiction writer, and they know that. They know that the characters are fictional—so I never felt it was any kind of a tightrope.

Look, there are times I’d have to ask some tough questions. Corruption was not the toughest part: the toughest questions were asking about police shootings of young unarmed African-American men. Those are tough questions. Everyone knows that there’s corruption, historically, in big-city police departments. And most cops are pretty clear-eyed about that. They’re not naive. I add that most cops, of course, are clean.

That’s an interesting aspect as well—because we’re focalized through Denny Malone’s viewpoint in The Force, a reader can emerge from the book with the idea that it’s near-impossible to be a clean cop and have an ambitious, rising career. But you’re saying that that’s not the case?

That’s not universally the case. I know a lot of cops who’ve had heavy careers, high-ranking officers, who are absolutely squeaky clean. At the same time, the politics of any big city or even small-town police department are always going to require the exchange of favours. Now, sometimes those favours are perfectly legitimate—but they’re still favours. There is no free lunch. You get a favour from someone, you’re laying down a marker that will be picked up, trust me.

There’s another kind of corruption—we have to distinguish. When you’re talking about police corruption, you’re talking about two separate issues. There’s financial corruption, which is pretty cut-and-dry: you take money or you don’t take money. You steal stuff from a crime site or you don’t. But the other kind of corruption, the type that’s related to getting your job done, which you alluded to in your question—there is a tremendous temptation, either for career reasons or for, believe it or not, ethical reasons, to cut corners, to lie on the stand, to do these sorts of evidentiary things to put someone away that you know either has or is going to hurt somebody.

I’ve had cops tell me these stories. I had a cop tell me about going to a domestic disturbance, wanting to get that guy out of there and not doing it because he didn’t have a legal pretext to do it, and then having to go back to that same address six weeks later because of the homicide case, where the guy did kill his wife. That’s not an uncommon story.

In a lot of these precincts, they know—believe it or not, it’s a small number—the 80 or 90 individuals who live there and who cause 85 percent of the crime. They know who they are—they’ve got their pictures up in the back room, where you can’t see. They know who these people are, and they know they’re going to hurt someone, they’re going to rob someone, they’re going to cause problems for the vast majority of people who live in these poorer precincts, who are just trying to get through their lives, raise their kids. There’s a great temptation for that second kind of corruption, to cut a corner, to lie about what you saw, so you have a pretext for bringing somebody in.

When you said it’s a very small collection of individuals who drive 85 percent of the crime, I assumed you were talking about the drivers of organized crime—but you’re actually just talking about just people on the street who are carrying out crimes.

OC—organized crime—is a different topic. [Cops] know the OC guys living in their precinct, but these guys are rarely committing crimes in your precinct. They live there, they might operate there, but the crimes are bigger things—and organized crime guys don’t defecate where they eat. If you want to get yourself killed, go ahead and sell dope on the block where the local OC guy lives. That can be a death sentence. But the OC guy has no problem selling dope two miles away.

On this organized crime tip—you’re just off The Cartel, and I felt unsurprised to see The Force become, at least partially, a drug novel. Not because that’s “what you do,” but because a crime novel at a certain level, when you’re talking about institutions in America, has to become a drug novel, because that economy is embedded.

Exactly. It’s difficult to write a novel about big-city policing, whether it’s New York or Chicago, or anywhere else, without writing about drugs. In 2016, it’s disingenuous to write that novel without writing about the heroin epidemic.

I’d rather not have been writing about drugs, frankly—but that’s just what it is.

You say the most difficult conversations you had were about race, about the shooting of young black men. Were you talking to people other than cops?

I wanted to write about the race issue—if you’re going to write about a big-city police department in 2014-2016, when I was writing the novel, you have to write about race. You just do. It’s the reality of our times, and that’s going to be a sensitive and difficult subject on every level. Whether you’re talking to white cops or black cops or Hispanic cops, or people in the community, it’s a difficult subject.

It’s America’s original sin. I often say the era of mass incarceration didn’t begin in 1993, it began in 1690: it was called slavery. And for at least two hundred years of our country’s history, the police were not used to enforce laws to protect black people: they were used to enforce laws to enslave black people.

I know this is not your problem to solve, but can non-racist policing exist?

I think it’s a matter of time. I think it’s a generational issue, and I think it will get better. When you talk to cops, more forward-thinking police, what they tell you is that this is a recruiting issue and a training issue. Some people shouldn’t be cops, because either they’re overt racists, or they have—as we all do—conscious or semi-conscious biases. We all come from the same society, so if you ask me are cops racist, I say yes—just no less and no more than the society from which they come. The difference is, with a cop with a gun, that unconscious bias can become lethal.

Denny does a certain part of policing well, though he does cut corners, indulging in that second type of corruption you were talking about, taking shortcuts for reasons he believes to be ethical. Malone cares, deeply, about his community. That’s why I’m always putting quotes around “dirty cop” and “bad cop” here. Denny thinks he is trying to be a good cop, and he is succeeding in some ways.

I think about character—I never think about good or bad, or anti-hero or those things. It’s not my job to make those judgments. My job is to bring people into a world that they otherwise couldn’t enter, and show them that world through those people’s eyes. So when I’m sitting down to type, I’m never making those judgments.

Denny’s a complicated guy, but most human beings are. As a fiction writer, it’s not useful to label people—but when I’m not on the job, I might have my own opinions.