When I meet John Irving in his mid-town Toronto apartment, he’s gleefully wielding a plastic piece of Canadian identification. He and his wife had just made the move to Toronto from rural Vermont permanent—or, as permanent as a move can be for someone whose work drags them, regularly, from continent to continent. The man contains allegiance to as many places as his novels do—the most recent takes us from Mexico to the United States to the Philippines, via the neatly geographically organized life of Juan Diego, who grows up in a garbage dump, joins the circus, witnesses a tragedy and a miracle and, late in his career as a writer, becomes a romancer of metaphysically questionable companions.

Places are on my mind at the beginning of the interview, and not just because of the nimble map-jumping that characterizes Irving’s work, or because I can look out his window over the tops of the trees and almost see the roof of my childhood home. It’s because Irving’s books, which have been a fixture in my life since I was probably too young to be reading them, are in many ways catalogued in my head more like places I’ve visited than novels I’ve read. There’s something vivid about the worlds he crafts that tricks you into believing you’ve experienced them in more ways than one.

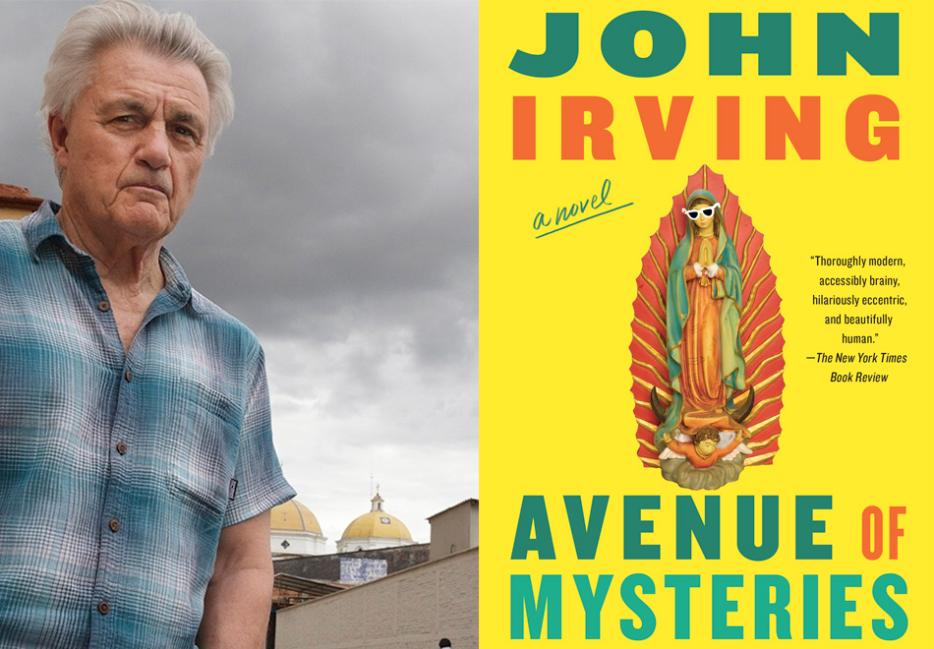

Those planes of experience—from clairvoyance to ghosts to miracles—are in full force in Avenue of Mysteries, his latest novel, which began its life as an idea for a film and grew into a book set over the course of a lifetime. It comes out in paperback this week.

*

Haley Cullingham: Are you someone who is preoccupied with other places, or do you find that you’re present in the location you’re in when you’re there?

John Irving: I think I feel pretty present in the location I am in when I’m there, because so many of my novels have involved being a kind of investigative reporter and imagining myself in someone else’s shoes, often someone from another country. Often if the character is an American, what’s happening to him or her is in another country, so I’m very familiar with being a foreigner. I was in university for a couple of years in a German-speaking country; one of my children was born in Vienna; I’ve lived outside the United States a lot, not only but including the years I’ve been in Canada. So, I don’t think I’m at all as American a novelist as many Americans are, in terms of what I write about and where my novels are set.

I’ve spent a lot of time over the years in Southern Mexico, and if you’re going to absorb a place you have to be there more than once. I think I like that aspect of becoming a kind of student before you can truthfully write about something, unless you’re just going to continue to write about yourself and your home town, and I’ve never been attracted to that idea. Even when I was a kid, when I hadn’t yet written my first novel, I was always just baffled by the idea of The Great American Novel. Why did American writers obsess about this seemingly patriotic-sounding vanity? I mean, if you want to write novels, well, it’s understandable to hope you might write a good one. But why does it have to be an American one? I didn’t get it, I never got it, I never subscribed to that idea. It makes me feel good that other people are questioning that notion—that is, other, younger American writers are saying, what was this about? I’m glad to hear a cynicism for the term itself.

I have not lived full time in a city since I lived in New York for most of the ‘80s. In that decade I lived in New York City, and I’ve lived in Vienna at many different times of my life. If you have dogs and young children, it’s great to live in the mountains or on the ocean or in the country. But when you’re a couple of adults rattling around in rooms that used to be full of your kids, and they’re not kids anymore, it’s kind of lonely. I realized that I really loved Toronto, but I also really loved being in a city again. I love not driving a car—I feel I could have written one novel in the time I’ve spent in a car. Frankly if I never drive a car again I’ll be happy. I love the subway, I love walking. I miss that. I missed that about living in New York.

Going to the idea of emptiness, the empty house in Vermont, that’s an idea that comes to light in a lot of your novels. Missing limbs, empty hotel rooms. But to me, in Avenue of Mysteries, that emptiness almost seemed to become an ambiguity: there’s a man who might be a father, there are travelling companions who may or may not be there, a leg that’s there, but it doesn’t work the way it’s supposed to. How does absence or ambiguity fuel your storytelling, and was there a shift for you with this book?

Oh, I think ambiguity is always important. Characters who aren’t what they seem always interested me. Characters who seem to know something that is preternatural for people to know about the future, for example. That wouldn’t be the first time: Lupe [Juan Diego’s clairvoyant sister in Avenue of Mysteries] has ancestors in earlier novels: Lily in the Hotel New Hampshire—she sees what’s going to happen, she jumps out a window; Owen Meany imagines he sees the future, he’s a little bit wrong, but he’s more right than wrong. And what he’s wrong about is kind of what makes the story. He imagines he’s going to die in Vietnam, he can’t quite see how, and he’s almost right. But he’s going to die in the United States—not in Vietnam, but because of it. Not in the war, but because of it. That’s the part of what he doesn’t know I meant to keep from him. We’ll never know what Lupe didn’t know.

I obviously like that ambiguous sense of characters who know something beyond the normal, or who think they do, who may be deluded in what they imagine they know but they think they know it. The more spectral figures of Miriam and Dorothy, the mother and daughter that Juan Diego sleeps with, with both of them, well, I think you have to be a very inexperienced man, which Juan Diego is, and someone who lives almost entirely in his imagination instead of in reality, which Juan Diego does, to imagine that sleeping with a mother and a daughter is ever a good idea. Most of us probably wouldn’t. [laughs] Just guessing. I wouldn’t! I think that’s a really bad idea!

But I always liked the idea, to say what you’re asking another way, about shift: the big shift in this story was for years to imagine it as a movie, which I did, as a screenplay, in which it was only the story of what happens to Juan Diego when he’s fourteen, and he loses his sister when she’s thirteen. It was only that story. The movie begins when brother Pepe meets either the missionary’s plane, or the children in the dump, it ends when Pepe and Rivera and the dog would be saying goodbye to Juan Diego, who’s leaving Mexico with Senor Eduardo and Flor. That would be the frame. Where I always imagined Pepe repeating, at the airport, as the plane takes off, “I’m already missing you.” What he says to Juan Diego in the church when he realizes the old priests are going to let him go. Well, I remember the moment very clearly when I thought, “Oh, you know, this could be a novel.” And if it were a novel, it would begin when that boy, that 14-year-old boy, forty years later, is 54, and he’s about to make good on his promise to the gringo draft dodger. He’s about the go pay his respects to the gringo’s dead father in an American cemetery in Manila. And I thought, well then, I could always—speaking of ambiguous, speaking of shift—keep alive those two women, all in black, mourners, apparently, in the front rows of the temple when Rivera brings Juan Diego with his crushed foot and deposits him at the feet of the giant Virgin Mary statue, and briefly, when the pain abates, these women appear to him, these mourners, and he imagines, for a second, that they must be mourning him, that he’s dying, and suddenly the pain is back, and when he looks again, they’ve disappeared, and he thinks, “Oh, I’m not dying.” And I would always think, when I was writing that scene, “Well, not then he isn’t. But what if we saw them again? What if they didn’t really go away, if they always attended him.” And I could make that happen only if he goes to Manila thirty, forty, fifty years later. Then there they are. In another manifestation. And that sort of was their ambiguity, and the ambiguity of mother/daughter or not, those ghosts, those spectres, those succubi as Clark would call them, maybe, whoever they are, they’re the same two who were there that day in the church, in the temple, when he first sees them, and they’ve never really gone away. That gave me another dimension, that was a kind of a telescopic lens, and I thought, that’s not a movie. That’s a novel. The “forty years later” part is a novel. But eighteen months? That’s a movie. All these years it lived as a screenplay in progress, and I suddenly thought, I said to the director, let’s just wait, let me do this as a novel first and then we’ll come back to it as a movie. Let’s do it as a novel first.

When we first meet Juan Diego as an adult, when he’s about to take this trip, he seems almost willfully stuck in that moment of “I’m already missing you.” His life is so steeped in nostalgia, and as I was reading, it made me want to ask you, what do you feel the function of nostalgia is? What does it mean to you?

Yes, there’s a line about him that he seems almost resigned to whatever will happen to him, which is a reflection I think of what is also in those early chapters about him that contributes to why he appears so much older than he actually is. He’s 54, looks 64, sometimes thinks 74. It’s more than the limp that does this. And I always imagined about him that, and this isn’t new, this is something I’ve often done in novels, the idea that if something cataclysmic or traumatic enough happens to you, at what I would call a threshold age, let’s say between the ages of 12 and 15, and think about how many characters in how many of my novels are focused on at that moment in time, when something happens, somewhere between childhood and adolescence, between adolescence and adulthood, somewhere at the onset of, during puberty or just before it, something can happen that is so formative that it not only contributes to the adult you will become, but as you grow older, it almost eclipses the rest of your life. It becomes more dominant, more prominent, in your dreams, in your memories, more vivid in your mind than any short term memory of yourself you might have.

I purposely wanted there to be very little in this novel about the intervening forty years. There’s almost nothing about his life in the United States, almost nothing about his life as a Mexican American, which he is so sensitive to being called, and that’s very much on purpose. It’s a way of saying, when something like this happens to you, at the age of fourteen, when he loses Lupe in the manner that he does, which he’s more than a little guilty about, well, everything else kind of pales. And the only part of his American story that is given as much as a whole chapter in the rest of the book, is the death, by AIDS, of Flor and Senor Eduardo, because he loved them, and because they loved him and did the best job they could for him. And they are of course concurrent to the woman he waits too long to ask to marry him, which is the other missed opportunity of his life. So, with the exception of that moment in the car with Dr. Rosemary, and the way he loses Senor Eduardo and Flor, it’s as if almost nothing else happens between the moment he leaves Oaxaca at age fourteen, and the moment when he undertakes, I don’t think it’s a surprise, this journey to the end of his life, to the Philippines. I don’t feel even saying it is giving too much away because he’s a guy with a heart problem when we meet him. And he already doesn’t like his meds. This is not a good combination of things. [laughs] If you’re taking heart meds you’re supposed to take ‘em, right? And you’re not supposed to mess around with the dose.

I suppose I could have given myself away more glaringly if I’d called the novel Death in Manila or something, and it is very much a kind of Death in Manila novel—it’s, I think, very consciously on my part a pretty obvious homage to Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice. I very much had Gustav von Aschenbach in my head when I was thinking of my older Juan Diego, who’s not so good at seeing so-called real life around him. He’s too much in his imagination to ask the kind of questions, even about Miriam and Dorothy, that it seems to me most of us would ask. Not only “What’s your cell phone number?” [laughs] But things like, how many centuries have you been around, actually?

Speaking of Miriam and Dorothy, as I was reading this book, especially when we get to the scene in the bookstore in Lithuania in which Juan Diego mistakes mail-order bride advertisements for the listings of a book club, I couldn’t help but imagine Dorothy, Melony from Cider House Rules, Hester from Owen Meany, having their own book club. Dream book club!

Good for you! Good for you! Those are all my favourite characters, including Emma, in Until I Find You, I like Emma, too.

How do you create these women?

I think so much of the literature I’ve loved, or the literature that’s served me as models of the form, is also populated with great women characters, that earlier Hester before mine, in the Scarlet Letter, Tess of the D’Urbervilles, the frightful combination of Estella and Miss Havisham, who control so much of Pip’s life in Great Expectations, not to mention that Flaubert’s greatest character was a woman, Madame Bovary is pretty special, so a part of it is a recognition that women have always been in classical literature, in perhaps greatest period of the novel, the nineteenth century, but also onstage, in Shakespeare, in Greek classical theatre, they make things happen.

On a more realistic level, I can’t tell you why this is but I believe it’s true, I think women generally have a much better understanding of men than men have ever had of women, probably because women have been under-regarded by men for much of the time, and have had to develop more of an understanding of men than men have bothered or taken the trouble to understand women. Is that changing, is it better than it was? Well, I suppose. But it’s ludicrous to me, not only because I’ve always seen abortion rights as an issue—it’s always struck me that there would never have been a debate about abortion and the right to an abortion if men could get pregnant. Ever. It’s as simple as that. But I think it’s kind of a repeated theme in my novels that many people who are minorities or who are treated as such, and women are treated as such, not only in my novels, but sexual minorities have always interested me as a writer, so I suppose that’s a part of it—that women are under-appreciated, or that their role as one in service to childbirth and childrearing is and has been for so long a way a kind of instigation to be attracted to, as you said, strong women characters in my fiction, characters that you can’t underestimate, or shouldn’t, right? That’s always been a draw—not least of them, in Avenue of Mysteries, Lupe herself, who is an uncomfortable and disquieting kind of authority, for someone who can only be understood by one person. And even to as genuinely sweet a man as Pepe is, Lupe gives him the shivers, he’s disquieted by her for reasons he can’t even explain or acknowledge to himself, and Pepe is not an intolerant man. I like that situation.

You also used a word for Juan Diego which is very true of him but true as well of many of my young male characters, passive, in comparison to, especially it often seems to me, the considerably stronger or more decisive women around him. Lupe’s the decisive one. She’s the one who tells him, we’re the miraculous ones. He needs to be reminded. He seems to forget. She’s also the one who determines what they do next. “We’re going to burn him, we’re going to burn the dog, we’re going to do this.” The ashes go to Mexico City, the ashes go to the basilica, to Our Lady of Guadalupe, and she’s the one who says, “Don’t you touch those ashes, they’re not scattering here.” Even on the bus before they’re back to Oaxaca, she says, okay, we go to the temple, we throw them all over the Virgin Mary, let’s see what she can do. I like that.

And don’t forget, too, that no questions asked, the most powerful character in the novel is you-know-who, who sheds tears—in other words, the whole idea, the premise, of making Lupe at the beginning so suspicious, even derogatory, or the Virgin Mary, the Mary Monster she calls her, not only for the size of the statue, and both Juan Diego and Lupe disparage Rivera as a Mary worshipper, well guess what? They become one. She wins them over. She’s the only one who delivers the goods. She cries. And I suppose what I always wanted to say with that is that the Catholic church, in 1970, in Mexico, what would it take, for them to condone and approve, the adoption of this boy, this orphaned child, by a homosexual man and his transvestite hooker lover? Well, it would take tears from the Virgin Mary, that’s what it would take, right? So, the real miracle may not be that the statue sheds her tears, the real miracle is that this kid gets to leave with those two. That wouldn’t happen in 1970, I don’t think it would happen now, I don’t think such a thing would be allowed.

And miracles have interested me before—there’s one in Owen Meany, there’s another one here. Juan Diego’s issues with the institution of the church, his issues with the man-made rules of the Catholic church or of any church, his issues with matters of church or institutional policy, don’t keep him from being a believer. Don’t keep him from believing the miraculous stuff, or wanting to. So in a way, the old dump boss gets the last word. In a way, what Rivera says when he walks out of the temple, when he points to the virgin, and says to the two old priests, “I come here for her, not for you,” he makes the point. It’s not the institution that makes Rivera religious, nor is it I think the institution, not just of the Catholic Church, but of most churches, of most faiths, that makes people who believe anything believe. It’s the miracle stuff. It’s the stuff you can’t prove. And most people don’t get to see the tears. [laughs]

Juan Diego doesn’t believe in the church, and he struggles with his belief, but he always believes in Lupe. He doesn’t know how much of the future she can see, but he knows she can see something.

Yes, but I don’t think he’s too hard on himself for holding himself accountable, for not listening more closely than he does. They all kind of miss the thing about her, and even the man of science, even Dr. Vargas, is left to spin his wheels in the sand forever doing research on rabies in lions, when it’s far too late to bother. When he should have been paying closer attention the first time she asked him, which he wasn’t, nor was Juan Diego. I could make that happen more easily by isolating her from other people’s understanding, and making her dependent on her interpreter brother, and sometimes the things he chooses not to translate you wish he had, because she’s a clairvoyant child with no adults to talk to, which is a dangerous combination. But there’s probably nothing I imagined so obsessively and that so sort of haunts many of the novels as the prospect of something happening to a child, which is what comes with having children, and imagination. It’s inescapable, if you have children and you have an imagination, that in your worst dreams, in your worst fears, in what wakes you up at four o’clock in the morning, you will, if only in your imagination, be losing them all the time. Those things aren’t in the nature of what you choose to write about, those are things more in the nature of what chooses you, no more than you have a choice about what’s on your mind when you wake up at four in the morning. You didn’t choose to think about that, it came and found you, hi, it’s me again. [laughs] I’m back! That’s what those things do.

Are novels a way of giving that pain, those 4 a.m. fears, a kind of utility?

That’s an interesting word, utility, yeah, but I like it better than the more common accusation of novels of that kind which, as you know, is “therapy,” or that you write about things you fear, or things you dread, or you write about not what has happened to you but what you hope never happens to you, or to anyone you love, as a way of holding them at bay. As a way of saying, if I exorcise this ghost, maybe it will leave me alone, but that’s wishful thinking, because guess what? They come back. They don’t go away, right? It’s never somehow enough to write about those things once. They will come back.

Not to make the process of dramatic or tragicomic storytelling sound entirely formulaic, but I’ve often thought that … I can’t tell you where it comes from but it seems to me now, after fourteen novels, that it pretty conclusively seems to be my job, or I seem to think it is, that I think of a sympathetic situation, meaning one that I hope will gain your sympathy for my principal characters, and then I think of ways to hurt them as badly as I can. [laughs] Why are we laughing? [laughs harder] It’s not funny! [laughs even harder] But it is what I do, you know, and I said that one night, not long after I met Janet, my wife, I said that to her one night and she whacked me! She said, yes, you do that! Well, it just seems it’s my job, it’s what you do, and speaking less gruesomely but more simply of storytelling as a craft or as a construction, to go back to your word, which I like, you better write pretty short novels, virtual novellas or long short stories, if there isn’t an element in them that makes readers more compelled to keep reading, at page 300, than they were at page 30. More compelled to read more at page 400 than they were on page 40. And guess what? After a couple of hundred pages, readers aren’t more interested because of your artistry, because of your intellect, or because of your craft. They get that already. They’ve already been impressed; you’re not going to impress them more. What makes you more invested as a reader, or makes me more invested as a reader, is that I suddenly feel I have an emotional and psychological stake in what happens to these characters. If I don’t care about them I don’t care what happens to them. If I don’t like them, why would I be interested in what happens to them. After 200 pages, I’d say, okay, that’s well done, but so what? A lot of things are well done. I’d do something else. You have to feel, “Oh boy, this guy’s in trouble. This is not going in a good direction.”

And I want you to guess what’s going to happen. I don’t want you to be wrong about what’s going to happen, but that’s not the same as wanting you to know everything. There’s always things I don’t want you to know, too, or there’s always things that you may correctly know. I think you’d have to be a pretty dense reader to not know that Juan Diego is going to die. This man is taking risks he shouldn’t take, he’s not seeing things he should see, the reader knows a lot more about what’s going on than he does. I like that situation too, I like it in theatre, I like it in film, that we think, “Oh my god, you asshole, don’t do that. Enough! Stop! I liked you, but don’t do this. This is just crazy.” Well, you want the reader to be anticipating the story. You want the audience in the theatre to be almost groaning and saying, “Oh no, not that girl, not her, please, wrong idea.” You’ve got to have that reaction, but you’re not going to have that reaction if you don’t feel some emotional interest that, beyond artistry, beyond intellect, those things, is visceral. And a part of that, for me, comes from, “Oh god, don’t let this happen to anybody I care about. No, don’t! Don’t go down that road, don’t open that door.”

I like that involvement and I suppose in addition to needing to know those last sentences, the tone of voice, not just what happens but how it sounds, what is the degree of melancholy or sadness or uplifting, if any, what is the tone? In addition to that, I have to know that there are parts of the story that I am not looking forward to writing. There are parts of the story that almost make me sick to think of—writing that scene, or that moment, the moment Lupe meets Hombre, for example, and knows something you don’t know, and speaks to this lion and of this lion in disturbingly familiar terms. That there’s a connection between this little girl and this imperious male lion that’s just unnatural, not a Disney story. It’s not cuddly. Something disturbing, and I always knew that, it was an early note, and like with Pepe, it always gave me the shivers, the part where the first thing she can say to Hombre is, “It’s not your fault.” There are moments like that that just, you can’t expect an audience to have an “Oh shit” feeling if you haven’t given it to yourself, if it doesn’t somehow turn you off, and make you think, “that’s uncomfortable.” How can you expect to then have that effect on readers or an audience? You can’t, if there isn’t something that disquiets you, why would you do it?

Lupe and Hombre are both really interesting manifestations of the idea of being underestimated. Was that deliberate, to have them face each other?

Yes, sure, sure. There’s something weirdly complicit even in the moment where he claws her once by accident, and there’s a kind of withdrawal, there’s a kind of retreat, but at the same time, he’s a cat and blood is blood. I’ve seen that in circuses. A lion tamer, a very sweet man, not an Ignacio, a lion tamer in India, actually, demonstrated this to me. I thought I understood the respect that the person working with lions had to have for the lion, but I kept saying, how do you calculate or know or read in the lion’s behaviour if it has or has lost its respect for you? How do you read that? Because it can’t always be there. That is, respect. It’s an animal. It’s not always there. There have to be moments when you know, now’s not a good day to make him get up on the chair. [laughs] Maybe we’ll skip the chair today, and let’s just play with the ball, he seems to be into the playing with the ball but something about the chair is putting him off. How do you read that? How do you know that?

This guy, his name was Pertab, he was doing his best to articulate this, which I could appreciate was a difficult thing to read, and even more difficult to explain to a foreigner, in more than one sense a foreigner, a foreigner to lions, who wasn’t savvy to what the different eyebrows meant, and the way one side of the nose could kind of flatten. You’d see these things over a period of time and you’d think, what does that mean? Something about the face has changed, something in the way the eye looks at you, it’s different. There are all these little things. And you know, he was being as scrupulous as he could in explaining this to me, and it was an interesting conversation, and then we were walking by some of the cages and it happened to be a meat day and so there was meat around and someone had a bone with [gestures a tiny amount with his fingers] maybe that much meat on it, and the gristle, on the cart, that the meat deliverers had left outside the cage. The lions were done eating, they were most of them sort of sleepy, and off to one side, but there was a lioness. She was lying down but her eyes were open, and that was the knuckle, the joint on the cart, and he said, “That’s what they think of you, that’s how you read what they think of you. But here is what you musn’t forget about them.” He picked up the joint with a thumbnail size piece of raw meat left on it, and he put his hand quickly through the bar of the cage, and squeezed it, and just a drop of blood went [clucks his tongue] on the cement, and this lioness, who was almost like a child nodding off, suddenly the size of her nostrils went [snorts] like this, and she was on that drop of blood so quickly that I almost fell over the cart. I thought she was coming right through the bars. They’re so big. But they move so fast, and she just didn’t want anyone to get that spot of blood before she got there. And she was looking to one side and to the other, and there’d have been trouble if another lion came for that spot. That was her spot of blood, she saw it first. And Pertab just looked at me after he’d put the drop of blood on the floor of her cage and he said, “That’s what you don’t want to forget. That’s what you don’t want to forget.” And I said, “Ooookay. [laughs] I get it! I get it! That was a good one.”

You mentioned that there are some character elements, and some plot elements as well, that echo back from other books in this latest novel. What motivates you to bring something back?

Oh, you know, the problem with the motivation word is it sounds like such a conscience thing—it sounds like a thing in the category of an intellectual decision—and I don’t know if the things that come back are really as thoughtful or as much a part of the decision making process as that. I think they’re more psychological or from the heart or coming from a place of recurrent fear. It’s no secret that I feel I write what I’m most afraid of. It seemed a difficulty at the time, when I was still a university student, and found myself married and with a child at a time when few of my contemporaries were either married or had a child, but I didn’t realize on a couple of counts how fortunate a coincidence that turned out to be for me. And one of them was as a writer, because I had already written things, I already was writing, I already was imagining myself as becoming a writer, but the process up until the birth of that child was strictly intellectual, artistic, a matter of craft. A mechanical learning process. And I had never thought of myself as a fearful or even anxious person, and suddenly, I was married, not sure I would have been if there hadn’t been a surprise pregnancy, had a child, because that’s what you did, and I had never before felt so ill-equipped to protect someone so helpless, that I felt an uncontrollable love for. I’d never loved someone or something like this, but this infant was so clearly helpless, and I was supposed to do something about it. And that was the moment my imagination started to look for things … I could point it to a day, when my imagination became grounded in worst case scenarios. It’s almost as if I had the tools to be a writer, I had the language, I had read the stuff, I had chosen my models to imitate in a fashion, to what degree I was capable, but I was like an actor learning lines, I was still running lines, I wasn’t off-script, you know, and all of a sudden I had a subject and that was the subject, the subject was, you’re afraid of something you can’t see coming, but you fear it is. You’re afraid of what you will be able to do to prevent it, not knowing what it is and how you could prevent it if you did know. And there were suddenly a host of things that didn’t motivate me, to use your word, to write about, but that I couldn’t stop myself from writing about, and they all had a focus on this helpless thing who could do little more than cry and smile, cry and smile. And I thought, well, this is also the way I go through, as a reader, those books that made me want to write. I’m laughing until I’m not. And I thought, well, I have a subject. But it’s almost as if I didn’t choose it, it chose me.