I’m sitting in a restaurant, and all I can think about is how I got to this point: eating oysters and drinking a cocktail made of bourbon, scotch, pine liqueur, smoke, and bitters. The fact that I can even call what I’m drinking a cocktail is the sort of thing that would make 14-year-old me shake his head in disgust. The fact that I went out of my way to mention that I like West Coast oysters more because they taste less briney to me would be considered a minor offense compared to the fact that I’m doing all of this on the Lower East Side while I jot down notes about one of the greatest pieces of art to come from the area, Agnostic Front’s debut LP, Victim in Pain, which was released 30 years ago this year.

New York City is always changing, always in flux. The place you know may hardly resemble the place familiar to people in a decade or two. Buildings might go up, or they might come down; one day it’s a dive bar, the next it’s a holistic day care center; the tiny apartment building your family lived in when they first moved to America from wherever they came from now rents for three thousand a month. It stinks, but New York is New York: nobody said it was fair, and it proves that on a daily basis.

Yet the Lower East Side was historically a measuring stick against which the entire city was compared. As gritty, ugly, or potentially dangerous a place as you might find, the Lower East Side was always rougher. Since about the early 19th century—when the part of the neighborhood then known as Corlaers Hook was so infamous for the sex workers who plied their trade there that it spawned the term “hooker,” and gangs such as the Roach Guards, Dead Rabbits, Plug Uglies, and other outfits comprising mostly Irish immigrants or their children roamed the Five Points section that was considered the worst slum in the world for its time—a visit down that way could help you figure out what group was struggling the hardest to come up in American society. The Irish came, then Jews trying to escape the wrath of the Czar, followed by African Americans, and Puerto Ricans who all just wanted something better. What they got was the Lower East Side.

“I got used to seeing large fires in that direction every night,” Luc Sante writes in his essay “My Lost City,” which looks at the Lower East Side from around the time he moved into the neighborhood in 1978. He goes on to say, about the blocks east of Avenue A, that the fires were “usually set by arsonists hired by landlords of empty buildings who found it an easy choice to make, between paying property taxes and collecting insurance.”

Today the Lower East Side has a Whole Foods. Today you have to make a lot of money to live on the Lower East Side. Today buses filled with tourists drive slowly past the John Varvatos store that used to be CBGB. Today I’m sitting here with a coffee that cost three bucks after finishing my cocktail and my oysters. The area was creeping towards this point a decade ago when I moved here, but when Victim in Pain came out in 1984, there wasn’t much reason to spend time on the Lower East Side unless you were an artist or in a band. These days, there are million-dollar glass box condos; in dystopian 1984, it was a grim, largely forgotten stretch of the city. Just browse any of the numerous photo galleries that keep popping up online depicting New York in the 1970s and early ‘80s: ruin porn featuring random things on fire in the streets, rubble that used to be a building, junkies passed out or dead somewhere near Tompkins Square Park, or some other reminder of yesterday’s bleakness. They show a much different time and place.

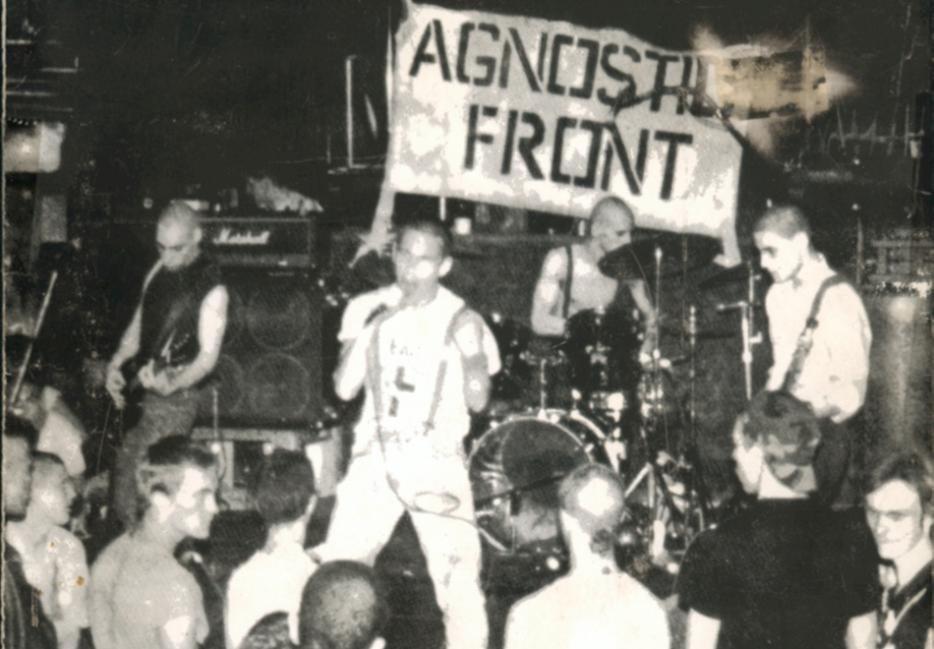

But those were the things that gave Victim in Pain its backbone. While the punk kids from California and D.C. came from decent families, some of the standouts the children of professors and government officials, New York couldn’t say the same for many of its bands. I don’t say any of this to question how hardcore any of these people are, or to make some sort of point that, in order to create a pure version of the tougher, more extreme version of punk, you have to come from any specific kind of background. I’m just saying that of all the hardcore to come out of the 1980s, the bands that best represented the anger and the struggle to rise above people and structures that held them down were the ones that called the Lower East Side their home base. And Agnostic Front was the best of them all.

“I got used to seeing large fires in that direction every night,” Luc Sante writes in his essay “My Lost City,” which looks at the Lower East Side from around the time he moved into the neighborhood in 1978. He goes on to say, about the blocks east of Avenue A, that the fires were “usually set by arsonists hired by landlords of empty buildings who found it an easy choice to make, between paying property taxes and collecting insurance.” Sante writes more about the “lunar landscape of vacant blocks and hollow tenement shells,” along with the heroin dealers, the muggers, and the other characters you probably didn’t want to run into on your own. The Lower East Side was the sort of grisly landscape that inspired Roger Miret, the Cuban-born lead singer of Agnostic Front, to write lyrics about how “We gotta stick together, support one another,” and to “Reject the system and their games” as he surveyed the situation before his eyes. It was a dying limb of the Great American City, an example of our failure and exactly how bad things could get, less than a decade after the city crawled away from the brink of bankruptcy.

Today, those kinds of lyrics wouldn’t really cut it among punks; they’d seem trite and played out and altogether too simple, with their overt references to friends, friends selling out, smashing enemies, smashing whatever holds you down, your crew, and whatever other hardcore cliché you can think up. But in 1984, Agnostic Front was creating the template that nearly every hardcore band from New York would follow for the next decade. Henry Rollins famously sang about rising above during his turn as the Black Flag singer du jour, but that was more than just a refrain for Agnostic Front—it was the message behind almost every single song on Victim in Pain. The members of the band were trying to see past the harsh reality of life on the Lower East Side, attempting to present an honest assessment of the streets they came from and what it took to get by. “We did what we had to survive by any means necessary,” Miret has said. “It was like a war or a battlefield, and we stood our ground.”

Even today, Agnostic Front and the bands they influenced—from original Agnostic Front drummer Raybeez’s Warzone to Gorilla Biscuits and Youth of Today, and later, midwestern powerviolence bands such as Charles Bronson—are barely an afterthought when people discuss New York City’s contribution to that era of music. CBGB, a spot that bands like Agnostic Front kept open long after Blondie started writing disco songs, is now treated like a holy place because the Ramones and Television played there. And, yes, those groups were and are important, but Agnostic Front was the true Lower East Side band.

Agnostic Front scared people too much to ever come into fashion. They were from the neighborhood, looked, sounded, and acted like it. They had shaved heads, wore chains for belts, and had lots of tattoos. They were scary skinheads from a bad part of town, and although their sound would move closer to metal, and become, dare I say, a bit more polished, Agnostic Front basically powered the entire New York Hardcore scene in the years that followed Victim in Pain. The record still stands up alongside hardcore’s greatest releases by Black Flag, Minor Threat, Negative Approach, and SSD—one that stressed energy and intensity above all else. “Nobody cared if you could actually sing,” Miret told the Village Voice, “but if you were a terror in the pit, you qualified.”

The day before I turn this piece in, as I walk through the Lower East Side to get to my office, the only danger I encounter is the close call with the three-wheel baby carriage that probably cost about the same as a month’s worth of my rent. The line is too long at Russ and Daughters for me to get the weekly bagel I’ve allotted myself, and the weak bodega coffee I’m drinking has me wishing I’d just spent the extra $2.50 at the place I headed to after eating my oysters.

The music sounds crude in comparison to today’s hardcore bands, which record in big studios, and have more money to try to emulate the sound Agnostic Front helped pioneer; it sounds primitive in the way they let it all hang out, without a hint of pretense. They weren’t exactly sloppy, but there is no one single thing about Victim in Pain that comes close to being perfect—not Miret’s voice, not the drumming, not Vinnie Stigma’s solo after Miret yells the guitarist’s name during “Hiding Inside.“ And yet, it all coalesces in the just over fifteen minutes it takes for the record to run its course—as flawless a hardcore album as you’ll find, a perfect product of the fraught time and potentially perilous place out of which it came.

The day before I turn this piece in, as I walk through the Lower East Side to get to my office, the only danger I encounter is the close call with the three-wheel baby carriage that probably cost about the same as a month’s worth of my rent. The line is too long at Russ and Daughters for me to get the weekly bagel I’ve allotted myself, and the weak bodega coffee I’m drinking has me wishing I’d just spent the extra $2.50 at the place I headed to after eating my oysters.

I complain, but as much as I try to deny it, it’s because I’m part of all of this. This is my New York City. I’m walking on the same Lower East Side streets where my own ancestors came to struggle a little less than they did in their corners of Eastern Europe that have long-since become other countries, nearly a century ago. The same place where countless others came and huddled in hopes of finding something better, only to get caught up in a century of decay before the turnaround of the ‘90s. Today, Victim in Pain plays like the soundtrack to that tipping point: one of the last true masterpieces of and from a different Lower East Side—one before the neighborhood started to turn into a place where, barring the occasional run-in with a rogue stroller, people could sip fancy cocktails and opine about the brininess of their shellfish of choice without a care in the world.