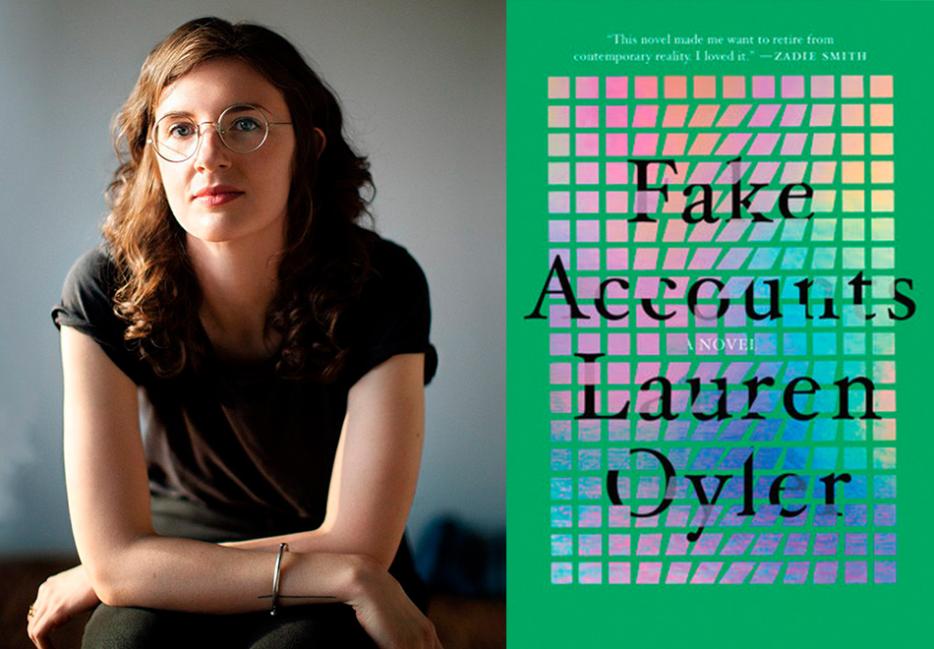

Lauren Oyler, best known for her fanged literary criticism, has written a novel of her own. Fake Accounts (Catapult) opens with a startling discovery on the eve of Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration: After snooping through her boyfriend’s phone, the protagonist-narrator learns he is an online conspiracy theorist, which gives her the gumption to break up with him. Newly resolved, she leaves New York for Berlin, where they first met. The impulsive one-way ticket is the most decisive we see the protagonist, who arrives in Berlin aimless and feeling vacuous. Capitalizing on being a stranger in a strange land, she goes on a series of dates and in each one assumes a different personality styled after astrological signs, trying them on and discarding them like costumes. That is, until a second revelation arrives.

I spoke to Oyler about the challenge of portraying evasive personalities, “fantasies of being found out,” and the class of millennial creatives who belong to the globetrotting “Easy Jet-set.”

Connor Goodwin: Is it hard to switch gears between criticism and fiction?

Lauren Oyler: I think the more difficult thing is actually writing for magazines and not writing for magazines; they edit a lot harder than if you’re writing a book. When I’m writing for magazines I do feel sort of guided by limitations—what I think the editor will change, the stylistic stuff I can get away with. When writing a book, I had to keep reminding myself I could do anything and no one was going to say, “We can’t do this because our readers aren’t going to respond to that.”

Reading this, there were definitely moments where I felt like you were wearing your critic’s hat. The protagonist is very analytical and makes some commentary on contemporary fiction. In particular, there’s one section where you parody the fragmented form, not just in format but down to the sentence-level. What made you target that style and why did you choose to include this particular section, which marks a sharp departure from the rest of the novel?

What I like about the novel is that it is a very flexible, capacious form. You’re not limited by truth. You can also put chunks of criticism in there. I was thinking about the obvious—Ben Lerner, Knausgård—but really, many novels will have long tracts stuck in there, and I always really like that.

I mostly wrote that section between 2017 and 2018 and, at the time, there were tons of fragmented novels and essay collections; the aphorism was really trendy. While I was writing that section, I understood the appeal of it because it’s really easy to do—you can really get into the mindset of thinking that way. I think there are writers who do it well, but I think it's a default structural thing when writers don’t want to think through the more difficult problems of their stories.

Aside from this section, most of the novel is written in chunky paragraphs, ballooned sentences, and really hones in on thought processes with microscopic detail. I’m curious how you settled on that style, and if there isn’t some element of criticism baked into choosing to write the novel in that way?

First and foremost, I just like it. I like getting really deep into one idea and parsing out all the implications of various events or feelings. That’s always what I’m drawn to in a text. If I put my contemporary critic hat on, I increasingly notice these books where I’m like, “You could’ve put more sentences in here.” I always want to know more about what the author is talking about, but then they move away. From a practical perspective, I imagine literary fiction editors and agents in particular working with young women authors encourage you to write a 75,000-word book that is compact and digestible with little Instagrammable bytes, which is a bummer. There are lots of great short books—who doesn’t love a short book?—but the short books I love the most also have these long, dense paragraphs where a lot happens.

This is a novel where voices are rarely singular. There’s the chorus of ex-boyfriends, the chatter of media Twitter—even the narrator's own neurotic, internal voice is self-negating and frequently reverses opinion mid-sentence. What drew you to write voices at that volume and, because they are so voluminous, was it difficult to keep the voices consistent?

There’s an illusion of consensus that is almost paradoxically produced online and [reproduced] whenever we take an idea or news story or an opinion from the internet and start talking about it offline among our friends. I think it’s natural to want to arrive at consensus, particularly when you’re faced with such large, insurmountable, incomprehensible numbers. The world is huge and that’s clearer to us than ever before, because you can see so much at once on the internet, and I think, frankly, the human mind is not capable of understanding the ways that trends and statistics work on a large scale. I wanted to press on that—criticize it, satirize it, but also establish that it’s very real. When [the protagonist] is at the women’s march, for instance, she sees this crowd going on forever and iterating forever. The fact that there’s so many people there in this one, overwhelming mass speaks to the same principle.

There's a section where she goes on a roulette of dates and in each one assumes a different personality styled after astrological signs; there's a sense in which this is not only a polyphonic novel but also poly-personality. How does the narrator view the self? Is selfhood always performative, or is there something essential nestled in there?

Even though she’s sort of funny and self-deprecating about it, she ultimately wants someone to say, “You’re being really weird and clearly lying.” I think that’s what she wants, particularly when she’s lying to her babysitting client and she’s having these fantasies of being found out. She’s imagining a world where there’s, not to use cheesy, social media corporate language, but fantasizing about having a real connection with someone and someone really seeing her. But they’re not going to [laughs]. She feels, in part, she should have some fun with it. So she’s tormenting these guys, most of whom I hope seem relatively normal, or at least not deserving of this weird performance she’s giving them.

I like that you said “fantasies of being found out,” because I felt like a core theme was this quality of elusiveness or evasiveness, which, to my mind, suggests there is something essential to be had about selfhood. And it also introduces this great tension between the protagonist’s analytical demeanor, maybe even the very project of writing itself, and how stubbornly evasive she is with regards to her selfhood, motives, and emotions, which remain mysterious to her and to the reader. And we have that same bundle of mysteries with regards to her ex-boyfriend, Felix. What about this underlying tension interested you? Was it challenging to represent that dynamic on the page?

Yes, very challenging. The most challenging thing was to have enough of Felix in there to make him seem really mysterious without giving too much away or not [giving] enough. I think there’s this tendency now to see analysis or criticism as something of a front, like a defense mechanism, and to interpret critique or neurotic intelligence as being fake and not allowing your true feelings to come out. And I think that’s really wrong. You can quite easily analyze your feelings and arrive somewhere else through analysis.

How would you describe the emotional journey you charted for the protagonist?

I came up with the basic outline of the plot at the beginning, which was quite useful. She snoops through her boyfriend’s phone because she thinks he’s cheating, but it turns out it’s a weirder, more shocking thing, which is that he’s been operating these conspiracy theory accounts. My initial idea was to have a sort of joke-y apocalyptic structure where the reader knows something bad has happened, or is about to happen, at the very beginning, and then you watch how it happens. So the idea was the apocalypse that’s going to take place is that she’s going to dump him, and then her certainty about this apocalypse is thwarted by the fact that he died. I found that idea very funny and the number of emotions one would have in that situation to be very fruitful.

From there, there’s quite a lot of stuff to do with that confusing morass of what’s happening—she thought she was going to have to process a depressing event, and now she has to process a totally different depressing event that there’s no precedent for. She goes online looking for personal essays people have written about their boyfriends dying, but they’re all very heartfelt. She also feels like she can’t tell anyone because she’s embarrassed by the conspiracy theory thing and she doesn’t want to seem like she’s heartless. So she feels quite alienated by her friends, even though she is alienating herself by not talking to them. That makes her go to Berlin.

I was interested in Berlin for this because I love it, but also because you think it’s going to be totally fine because everyone speaks English, but the fact of being in a new country where you don’t speak the language and don’t know anyone [makes] you sort of helpless. So she becomes even more alienated and I think that’s what produces this weird project she embarks on.

Did setting this in Berlin specifically contribute to these themes of inauthenticity, evasiveness, over-analysis?

Absolutely. The protagonist is very proud, obviously, and she has this analytic capacity she uses for evil a lot of the time [laughs]. When she’s in this Berlin setting, she’s constantly tested to do new things.

More generally, the Berlin ex-pat culture has not been written about a ton in fiction, and I think questions of authenticity are very important to them. You see generations of ex-pats who’ve shown up at various points and each new generation thinks they’re the “real” Berlin and the new people don’t actually live there and are faking it.

You’ve tweeted before how you like “sad girl in Europe” novels. Were you reading anything that informed your writing of Fake Accounts?

What was important to me was to establish the protagonist is very new to Europe and she’s part of this class of Americans who are a part of the Easy Jet-set—this international creative millennial class, for whom traveling around Europe is not this elite or special thing that it once was. But, crucially, we all know that used to be the case and we’re sort of nostalgic for that. I really like Elaine Dundy’s The Old Man and Me from NYRB, about a woman in Paris, and I really like Christopher Isherwood.

There’s always this temptation of meaningful history all around you in Europe that I wanted to resist in the book. History is pretty touristic now, particularly in Europe and particularly in Berlin, where there’s quite a few exhibitions just walking around. Have you been there?

No I haven’t, but I read Red Pill by Hari Kunzru this past summer, also set in Berlin, and he does lean on this history stuff, and I felt like that was a move you could’ve made and didn’t and was curious why.

Yeah, I think there’s always this fiction of like, “Here’s the history section of my Berlin book.” [The protagonist] is really alienated so she’s not going to be on Wikipedia learning about the Berlin Wall or whatever.

My favorite street in Berlin—not really my favorite, but that street where she’s riding her bike and there’s this trolley, this old [German Democratic Republic] car. And on the other side of the street is the Topography of Terror exhibit, which used to be the SS Headquarters, more or less. The thing that’s separating the SS Headquarters exhibit and the road is the Berlin Wall, which is so literal to me. It really encapsulates many tourists’ fake relationship to history.

I gotta say, when I saw you were coming out with a novel, I envisioned writers lining up to take a whack at this debut like a piñata. Is that in your mind at all, on the eve of this release?

I really believe if you’re a writer and you’re lucky enough to publish a book and it gets attention, you should be able to take it. My mom used to say [to me], “You can dish it out, [but] you can’t take it.” I think it’s only fair. I do think, quite candidly, the fact that everybody is expecting so much attraction means it won’t be as exciting as it would be if it were coming out of nowhere, you know what I mean? I am gossipy-excited to see who gets assigned to review it and who says what.