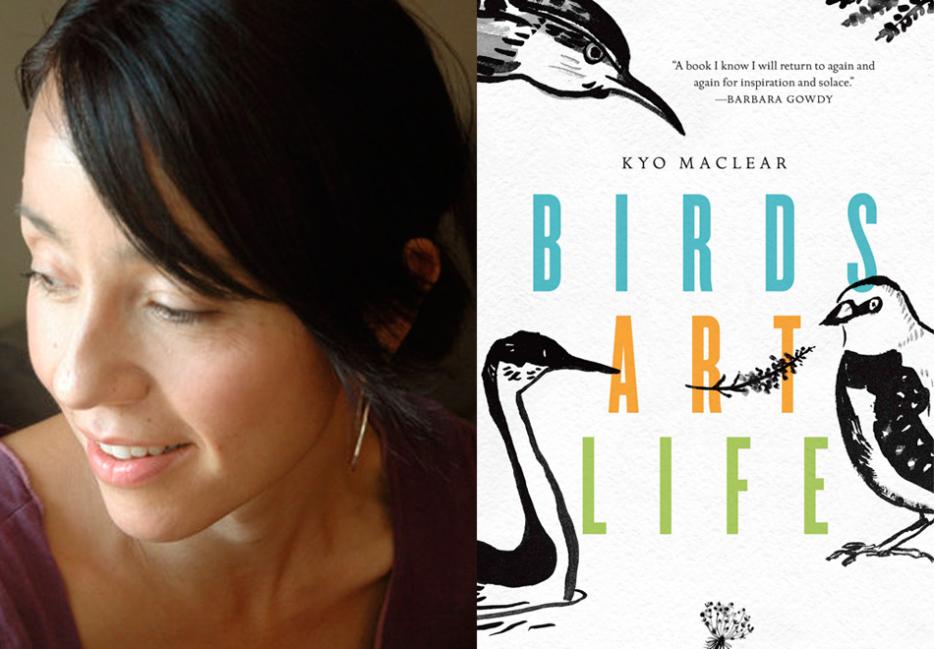

Kyo Maclear skirts and samples fact in her fiction. In her picture books, word play often becomes literal. Virginia Wolf posits the animalization of Virginia Woolf’s bad mood, Julia, Child imagines the cookbook author reverted to childhood. Her most recent picture book, The Fog, licks at the realities of global warming, but through the eyes of a people-watching bird.

Birds Art Life (Doubleday Canada), Maclear’s first title to officially live in the bookstore’s nonfiction section, flips that perspective. Whether working in fiction or non, Maclear is reaching for a whole story, a more full understanding that neither could truly tell on their own.

In Birds Art Life, she chronicles a year, she contemplates art, she looks at birds. She follows around a man she identifies as “the musician,” though his primary role is as a non-commital guide to the solace of urban birdwatching. She wants to find the missing piece, a way back to her life before it was shaken by her father’s unreckonable illness. But there is no widget to be found, only a new understanding, a clearer emotional truth.

When Maclear and I sit down at a picnic table in Toronto’s Trinity Bellwoods Park on a blustery weekday afternoon, she is quiet, clutching her coffee and shivering just a little. Maclear’s particular way of being quiet is patient. Thoughtful, easy. She is generous with her attention. For the last third of our conversation we are interrupted every few minutes by an uncomfortably close and alarmingly fearless squirrel. The interview slowly melts into elaborate personal stories of past squirrel encounters, none of which are transcribed here.

“A spark bird could be as bold as an eagle, as colourful as warbler, or as ordinary as a sparrow, as long as it triggered the awakening that turned someone into a serious birder. Most birding memoires begin with a spark bird [...] I began thinking about “spark books”. It occurred to me that most ardent readers would be able to pinpoint the book that ignited their love of reading.” - Birds Art Life, page 113

Serah-Marie McMahon: In the book, you describe the summer as a pre-teen in Japan when you felt yourself become a reader, and you list your friends’ spark books, but nothing of your own. Does one exist?

Kyo Maclear: I’m not sure if I have one specifically. I had a fetish for Oscar Wilde's The Selfish Giant, which is bizarre looking back. I can't read it without cringing now—it’s so heavily Christian, its symbolism so overwrought. But something about it resonated. My copy was lovely, illustrated by Herbert Danska. I still have it.

When you’re a child, adults are kind of giants. They dwarf you in different ways, with their power. This giant was captivating, how he reforms through the child figure. He was beautiful to me. And there was this garden. It’s a bit of colonial story, but The Secret Garden was also very important. Gardens enchanted me, especially the hidden garden, the walled off garden. These little Edens, little Utopias. I found them magical.

Did you have a garden growing up?

In England we had a garden. In Toronto my mother uprooted everything growing in our backyard and built a Japanese rock garden. It was her attempt to re-envision the landscape in a way that felt familiar to her. I grew up with a lot of plants that aren't native to Ontario or Canada, but yeah, I always had a garden. Do you have a spark book?

I think mine is From the Mixed-up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E.L. Konigsburg. That book was really important to me, it opened my eyes as a kid to the nature of independence. That you don't need to rely on your parents to provide your sense of wholeness. You can go find it yourself. And maybe it will be messy, and maybe it won't turn out exactly how you think, but you can be responsible for your own happiness.

Oh, I loved that book too, for the same reason I think. I was always attracted to what I call “orphan stories,” even if the parents were there. Kids who took off, and through their own wiliness had these great adventures. The idea of staying overnight in a museum was enchanting to me. I grew up in museums, it was a rare common bond between my mother and I. It was a space we could connect through, with pictures in a way we couldn't through words.

Both your books this year revolve around bird-watching. How do you tell a story differently with a book for children than you do with a book for adults?

Everything I do is in the same house, but it's all taking place on different floors. My kid writing floor, my adult writing floor, my scholarship writing floor—I'm writing a dissertation now. They are all different ways of telling stories, but they are all concerned with the same themes.

I find myself thinking a lot about kinship, how we might form it in more inventive ways. In The Fog, a human and a bird find a sense of kinship, these little lone wolves finding each other, understanding and really getting each other in a way that their own species don't. In Birds Art Life I found this weird kinship in a totally motley crew of urban birders, somewhere I never expected to find a sense of community. I'm generally not a person who seeks community. I'm such a solo person, almost agoraphobic. I like the idea of finding tribes in ways that are non-tribal, and that are unexpected.

What is the role of an illustrator in authoring a picture book?

I love what images can do, above and beyond just parroting the words. A really special picture book will take a story into another dimension, provide something atmospheric. When we were working on The Fog, I sent the illustrator, Kenard Pak, a link to an old book. It was from the ’60s maybe, called Hide and Seek Fog. It had a real sense of atmosphere to it, the pages almost felt damp with fog. I could have described that feeling in words, but Ken captures it so beautifully with his clouds and mist, above and beyond anything I could ever design. I love the collaborating. It's something I gravitate towards again and again. Doing something that is not solitary.

You both avoid community and are attracted to work specifically that is not solitary.

It is contradictory, I know! I think maybe I am comfortable when there is a structure and context. I'm socially awkward in so many ways. Being part of a project makes it easier. Truthfully I just love creating things with other people. It's pure joy.

What does that collaboration look like?

I always have art notes in my manuscript, take-it-or-leave-it notes. I don't intend to be a guiding hand, but I give over a lot of the motoring along of the story to images, and I need to actually be specific about what I'm intentionally leaving out. Whenever you see words in the art, I've written those. Other times I leave gaps and ask the illustrator to please fill it. To create a wordless spread that captures a certain sensibility, or whatever.

Sometimes in my text I play the straight man. I want the beat to fall on the illustration, so there is kind of a de-dant de-nah. I leave it to the illustrator to finish the thought, to imbed humour in a way that plays up the earnestness, makes it a little funny.

That needs to be a conversation between two people, you can't do it if you're the only person creating something. It's not monologic. It's not a monologue, it's a dialogue. You can create a lot of humor that way. I really need to have a sense of play to derive any pleasure from what I'm doing.

Most of the interpretations of The Fog include a strong environmental message, but I read it differently, as a metaphor for depression.

Well, that fits in with my whole oeuvre, which is mood disorder. [laughs] I’m always somehow dealing with themes of depression, or anxiety, or OCD.

I don't even know if depression is exactly the right word. Being too much in your own head. But once you connect other people and realize they feel the same as you, it gets easier. The fog begins to clear.

I love that. I hadn’t thought about it that way, but I mean it fits. It's about the idea of naming things, having things named for you. How important that is. How you are in a squishy and uncertain place before things are defined or a consensus is made about what's happening. So there is also that theme of normalization, how you can get accustomed to the most inhospitable conditions.

You talk about the idea of a “the new normal” in Birds Art Life as well, what we accept as our new baseline.

Right, the shifting baseline. One conversation I had with Ken, which I think is still unresolved, was the kind of open-endedness of the conclusion. Some people are going to have a hard time with it. People who want it to be more pragmatic, have an environmental message about how everyone took action, how everyone put solar panels on their houses and the fog disappeared through collective action. It's really not that. We veered away from that story, despite some counsel from a good friend of mine who's a climate change activist. He suggested we might want to be more activist, but we felt like it was all implied.

We left it to the reader to come up with their own ideas about where this story should go. The ending isn't conclusive. The bird and the girl are left thinking about what to do tomorrow. The reader still sees all these messages in the water, and there’s a sense that something else is going to happen, but we didn't want to tie it up in a tidy bow. Ken was really very adamant about that.

I wanted to ask about the girl, the human part of the relationship in The Fog. Did she come out how you envisioned her?

Ken and I had talks. Because he's also Asian I could be forthright with him and say: I want the Asian character to be Asian. I don't them to be racially indistinct or some ambiguous any-ethnicity. I want them to be look really East Asian. And he's like: got it. He had planned on doing that anyway. It was nice to have a conversation where he didn't get defensive, where he understood right away.

It's not just that I want there to be more children of colour in picture books, I'm also increasingly interested in how certain ethnicities are not seen in nature. We see a lot of stories of Asians in cities. I'm trying to figure out ways of telling stories that are unexpected in setting, placing characters where you wouldn't necessarily assume them to be.

I read the post you did last year about identity and representation in children's books. Do you still feel the same way?

Yes. I feel like I could add to it now though. It was a very modular piece about the need to parse this idea of diversity. There are many different kinds of diversity, and what we've seen is a resurgence of casual diversity. Everybody and their uncle, and their sister and their, I don’t know, dog, are writing books where there's some sort of rainbow tribe. I think that's really well intentioned, but it stops us from asking questions about what inclusion really means, who's writing picture books, and what publishing looks like. We needed to be more specific in this conversation.

Since I wrote that piece, people have drawn my attention to things that I hadn't noticed before. Like about how animal stories are not neutral sites. My friend was talking about Finding Dory, and how she felt the characters were particularly white in certain ways. How it's culturally coded. I don’t know if I would have thought that way, or questioned animal stories, or like, stories about shapes. Those too can have assumptions embedded in them—about who they are spoken about, and who they are spoken for. It's an ongoing conversation basically.

Your picture books, while being very much for children, definitely appeal to adults. Not in the Disney movie way of winking pop culture references over the kid’s head so parents don’t fall asleep, but that seem to understand how to tell a powerful story. How considered is your audience?

This actually preoccupies me. When you publish a kids book it will say ages 4 to 8, or whatever. I know why they do it, but in some ways I wish they wouldn't. I write picture books for all ages, which is not to discourage children as readers. My books can be entered at different levels. That's the way I'm writing them.

It's such a silo, you know? Kids Books. It's such a silo. All books should be read by all people. I like the non-categorical books, books that jump fences. I'm drawn to those. So why not let picture books jump fences too? Why not put them in art sections, or Julia, Child in the cookbook section? I mean, why not?

A great picture book has more in common with the poetry section than with some things in the kids’ section, like a middle grade novel. Not because picture books are necessarily "poetry" in structure, but because they are siphoning down such big ideas to so few words. The rhythm is so important, in a different way than it is for a novel.

Yes! Yes. And I don't know if a poet would cross over as successfully into middle grade as they would into picture book writing. Anne Michaels did it well, but I think it can be difficult. I’m sure there are some unusual middle grade readers who don't care about plot, but at a certain age there’s an impatience with just beautiful language.

I've been thinking a lot about Hayao Miyazaki’s films, partly because I'm writing about it right now for my academic work. In an interview with Roger Ebert he talks about this idea of the gap—what he calls the japanese word ma—the kind of stillness that doesn't move things along.

In picture books there are so many moments like that. In Miyazaki films there are so many moments like that. They are usually concerned with nature, and take place in a field of grass that has nothing to do with the plot. The background rushes to the foreground, and suddenly you're by a stream. It’s given you insight into the character's temperament, or mood, but it's not actually about plot.

Picture books can allow for those moments, capture its beauty. I think that's why I return to them again and again. That stillness is so important. I almost have narrative sickness. I'm tired of narrative. It's weird.

I want to end with a line I loved in Birds Art Life, "The more I encountered the reality of birds, the more my secondhand impression of birds began to fall away.” Do you think this is also a role kids’ books can perform?

I think that’s true of really good kids’ books, to defamiliarize the familiar so that we can see it again, but in a specificity. We tend to fall into habit-mind, like with a drawing exercise. You draw the vase, or the flower pot, or whatever, and you're doing it from habit-mind. It looks a certain way. Then someone asks you to do a blind contour, and now you're really seeing it. You’re seeing every change and texture, every little detail, every chip. Kids’ books should do that particularly well.