Rachel B. Glaser’s Paulina & Fran is like a really good dance song—catchy, fun, running on emotion. It’s a rowdy campus novel that goes beyond the typical framework of binge drinking and casual sex to explore something a bit more sinister: female friendship.

Paulina and Fran are seniors at a New England art school. Fran is a quiet painter, and when Paulina isn’t contemplating Art History (a major the school crafted specifically for her), she’s perfecting her seductive dance moves or formulating homemade products to perfect her curly hair. The two are fast friends until, one day, they aren’t. What’s released then is painful to watch but recognizable: backstabbing, boyfriend stealing, artistic and aesthetic competition.

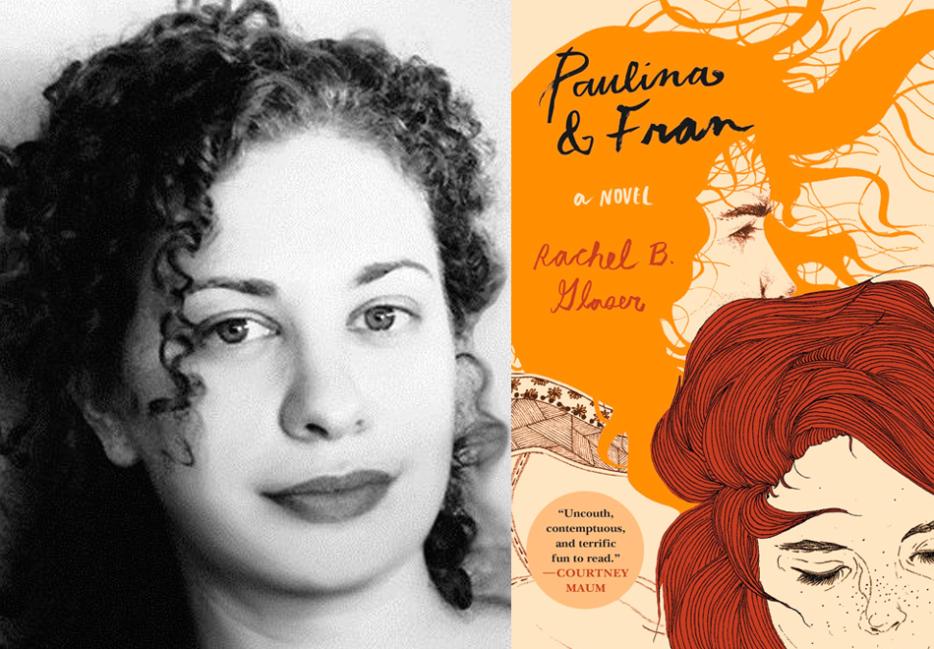

Rachel B. Glaser was kind enough to speak with me over the phone where we discussed, among other things, author photos, the discomfort presented by fictional characters, and how a good hair day can be a prophetic indicator of life going well.

*

Rachel Hurn: Are you familiar with Eileen Myles?

Rachel B. Glaser: Yeah, I really like her.

RH: I was thinking about this idea of female friendship and competition that comes up in Paulina & Fran, and I was reminded of something Eileen Myles said in a talk she gave to the St. Mark’s Poetry Project back in 1994. I’ll read you this one section. She says,

“There is a word in Italian, affidamento, which describes a relationship of trust between two women, in which the younger asks the elder to help her obtain something she desires.

Women I know are turning around to see if that woman is here. The woman turning, that’s the revolution. The room is gigantic, the woman is here.”

This is not the same as Paulina & Fran, because the women in your novel are the same age. But there is this idea of competition and friendship, and it’s a common theme that comes up in literature and with artists. What’s your experience with this been? The healthy thing, to me, is the mentorship idea, and the thing that ends up happening is often jealousy and competition. It seems especially prevalent with women, which your book reminded me of.

RBG: My friendships with women have been really positive and not like the friendship in the book. But in life, I think there are some people who find themselves on the opposite social landscape of another person, of someone they normally could get along with, but they’ve been put in a situation where there’s some sort of social obstacle between them. That’s part of what’s happening in the book, among other obstacles.

RH: Have you had much experience with that particular obstacle in your own life? Was any of that drawn from experience?

RBG: Some of it. The relationship in the book is a combination of different situations I’ve been in and some I haven’t. But yes, there are some friends you can be friends with with no qualms and no complications, and then there are other people you drift apart from.

RH: Let’s talk about Paulina’s character. She’s so wonderfully unhinged, but she’s also very compelling, which is probably true about a lot of unbalanced people. In one of our first experiences with her, she gets declined friendship by this girl, and the book says, “It had been a stunning rejection, one Paulina wanted to try on someone else.” That is so dark! I feel that most people would get hurt, but they wouldn’t want to hurt anyone, or maybe they would want to hurt the person who hurt them, but not take it to this next level. To try it out on someone just because they can. And then later, Paulina is jealous of the dead girl at the funeral, is jealous because of all the love and attention she’s receiving. It’s so funny, but it’s also so fucked up. Is Paulina supposed to be a sociopath?

RBG: When I was writing it, I definitely didn’t think, “Oh, I’m gonna write this sociopathic character.” I guess the response it a bit more severe on her than I feel. In fiction, I like characters who say what they think and shake things up. I know some people have found Paulina so distasteful that they had trouble reading the book, but I’ve been hearing from other people the experience of feeling critical of her but then relating to her in a few moments. I’m really interested in that experience. A lot of the things she feels and says aren’t so far from myself that I’ve never felt something related, it’s just more like a passing thought. Something maybe you think but then you reason with yourself, “That’s ridiculous. I can’t believe I said that.” I like how she just gets it on the page. I like seeing the waves it makes in the emotional space of those around her.

RH: Paulina’s doing the same thing we all do. There are certain things that she does that maybe some people wouldn’t do. But for the most part, I agree, it’s a more in-depth look into the way we can all be or think or feel. I found her really compelling, even though there were distasteful things about her. It wasn’t as if I hated her character too much to read her or relate to her.

RBG: It’s been reminding me that everyone is reading the same words, but each reader has their own relationship with reading. For people who read a lot of fiction, Paulina doesn’t shock them. But then for people who normally read a lot of nonfiction, they’re feeling, “Why should I care about this character?” Or, “If I wouldn’t hang out with this person in real life, why am I spending fifteen hours with them on the page?”

RH: What do you think that difference is? Where does it come from? There are people who find fiction and literature to be these great life-lesson moments, whereas some people feel that since it’s not real, it’s a waste of time. Maybe it’s just differences in personality—maybe it’s not even a question that can be answered.

RBG: I’ll give anything a try! I really don’t like horror films. I won’t watch them, and I even try not to watch the previews. A lot of my friends watch them, so it’s interesting to think there are a lot of people who like to feel that feeling of being scared, even though I hate to feel that feeling. It might be a more severe example, but I think with fiction, some people, when they’re reading, they feel like they’re dropping themselves into another world and it’s an escape. And other people are maybe less able to leave themselves behind. So maybe it feels like they’re putting themselves in the book. You know how there are some dreams where you’re a character in the dream and people are interacting with you, as opposed to other dreams where it’s like watching a movie, and you’re not even there? I think some people are judging Paulina as if she’s auditioning to be their friend.

I love the show Curb Your Enthusiasm, and my mom is unable to watch it. The tension is too much for her, and she has to leave the room. Where for me, that tension, that weird feeling, is one of the show’s greatest accomplishments.

RH: I feel the same way about horror movies. I find no enjoyment with them. I take them too seriously, and they make me feel too uncomfortable. I could see people having a problem with the discomfort and not even wanting to deal with it, especially if they’re the kind of person who really loves to read something super factual or historical, cut and dry.

RBG: Maybe it’s about disassociation. Some people love being thrown into a character, and maybe other people feel like they don’t want to know what someone else is thinking, and it makes them uncomfortable to be within someone else.

RH: It reminds me of this thing I do. If there’s a person playing a joke on another person, and I know what the reality is, and I’m watching this other person experience the feelings of thinking one thing when really it’s another, I literally cannot watch it. It’s to the point where I’ll be like, “He’s joking! It’s okay! He’s joking!” I can’t go along with it. I give things away. Can’t keep secrets. It’s too uncomfortable somehow.

RBG: Because you’re being asked to accept two realities at once. The truth, and then what’s being shown. There’s a weight to that.

RH: Paulina describes Fran as a girl who “she wanted to be, or to be with, or to destroy.” I’ve felt that way about people in my life, men and women, and it’s a really interesting human situation. Do you think it’s fear of rejection?

RBG: I think it’s totally related. It’s almost like someone strikes you, and it’s this dissatisfaction. This desire to either be so close to them that they become part of your life, or to just forget your life because their life is so great, or to just be rid of them forever. You can’t make sense of them. It’s almost like fear of one’s own excitement.

RH: Again, it’s too uncomfortable. Takes too much effort to understand.

I also wanted to talk about your similes and metaphors. A couple of them specifically: “She looked like a doll whose factory-made hair was not meant to be brushed but had been brushed violently.” Also, I underlined this next one twice and wrote “Yes!” in the margins because it’s so perfect: “Her orgasm was like a shooting star one pretends to have seen after a friend ecstatically points it out.”

Metaphors, for me as a writer, I tend to avoid them. I think I’m afraid I’m not good at them, so it was striking to read a book with so many on-point metaphors. This is more a question about style. Did you hone your metaphorical skills, or did it come naturally?

RBG: I’m so glad you liked those lines. I’m really excited by lines that take the reader out of the reality in order to show something. When I’m reading, if that’s done well, I get really excited. It’s almost as if you’re doing a kind of traveling—not exactly time traveling, but you’re being beamed into another reality. There were a few stories I wrote in undergrad, almost precursors to the novel, and there were tons of metaphors back then, but they were way more visual. I think now they’re a bit more emotional or trying to explain what something feels like. More sensual.

RH: Especially looking back on early versions of things, and being able to have the perspective to know what you were trying to do, but seeing that it isn’t being done yet. It’s like a problem that has to be fixed within the work itself.

RBG: I think before I was taking something visual and describing something else visual. There was one line in a story from twelve years ago, describing the way beer was sloshing around in someone’s cup, and I compared it to the sea or something. [Laughs] It’s like giving this visual or motion-like thing, but now, the visual about the factory-made hair being brushed, it’s explaining how Paulina feels about her hair. It’s giving us a more specific emotional thought.

RH: Because it’s also a very emotional act or description. Imagining a child brushing their doll’s hair violently. There’s an emotional connection there too that’s suggesting something a little dark.

RBG: Yeah! It’s making me realize another thing it’s doing is it’s taking you to a parallel scene, there’s an action happening. It’s not just, “The clouds were white like marshmallows.” It dips into a different reality to show something.

RH: The same thing with the orgasm one. Ultimately what you’re saying is, she didn’t really orgasm, but she’s pretending that she did because she feels that she should have.

RBG: Yeah. And with stargazing, you see a lot of things that feel like they might have been shooting stars, but you’re not sure if it’s just that your eyes darted one way or that it was a plane behind trees.

RH: Right! So it goes one step further. Not only should she have orgasmed, but maybe she did. And she’s not totally sure that she did or not, but she’ll convince herself that she did.

I also loved the line, “She pictured the paintings she wanted to make and the things people would say about them. And how she would look next to the paintings, having made them.” It’s a great relatable moment as a writer, as an artist. Don’t we all do this? It’s so much easier to daydream about what we will accomplish than actually working on the thing we need to accomplish.

RBG: Totally. But I also think that is part of doing the work. Years before my first story collection came out I would draw the cover, or what I thought would be the cover, and I’d imagine it in my mind. It convinced me that it was possible. It made it seem like it was already happening.

But also, let’s say you just had a good night out. You’re having all these ideas, but you haven’t been writing them down, and it’s like, “Oh, I’m gonna get back and work. It’s going to go so well.” It’s a sensation, not the reality. And then to actually get back home and try to remember those ideas... If you have an idea, and you don’t linger on it because you get distracted by the idea of what it could be, this infinite feeling of what the future could bring or what you’re capable of, it’s a really intoxicating feeling that might even feel better than actually doing the work.

RH: Oh, yeah, it totally feels better than doing the work! Usually. Unless there is that moment where you’re like, “Oh shit, the work’s going well.” Yeah, that feels better. [Laughs]

RBG: But then that feeling is often followed by, “But is this good? I thought it was good, but it is?” It’s that doubt.

I thought of something regarding the question you were asking me about female friendship. Which is, there is this connection between all the exes of anyone you’ve ever dated. There’s something you have in common, that you both loved or spent time with a particular person, but there’s something taboo because in some way there’s competition. You both had a similar love goal at one point. Whoever you’re dating, there are also these predecessors.

RH: You mean thinking about your partner’s life with previous people?

RBG: Well, more like your friend’s life now and your life now. It could be that you both dated the same person five years ago, but there’s a cosmic link between you that associates you to them but also distances you. It seems like it would be hard to get very close to someone who you’ve been in that situation with. Jealousy and possession.

RH: And then complicating it with wondering if you were ever compared against them. Like with Paulina, Fran, and Julian: there’s the situation of Julian dating both women, they’re passing him back and forth. It’s as if he becomes an object.

RBG: Definitely. They’re connected, even years after they’ve spoken.

I’ve always been fascinated by the relationships my boyfriends have had before me. One of my boyfriends from high school dated this singer-songwriter, and I found song lyrics that were about him. This was years later. But it still felt like such a good find! I’m looking for, wanting to relate to these people. To feel a connection with these people even though they don’t know I exist.

RH: Let’s talk about the curly hair theme. I’m not a part of that cult. It appears that you are. You have curly hair, yes?

RBG: [Laughs] Yes.

RH: I mean, this is just based on your picture in the back of the book.

RBG: I felt a lot of pressure about that. I felt like I needed a picture where my hair looked curly and looked okay, but I didn’t want it to be … I don’t know. It was hard to get that picture right.

RH: Like a little bit unruly, but nice-looking ...

RBG: Yeah.

RH: Has that been a common theme growing up? Thinking a lot about hair? Or finding yourself making friends with people who had similar hair? Or am I going too far here? I mean, I’m really tall, so that was always something for me. In high school, for some reason, there were no tall people. And it wasn’t until I went to college, that literally all of my college roommates were 5’10” or taller. And I was like, “My clan! My people! It’s okay that I’m tall!” Did you have similar experiences with curly hair?

RBG: Yeah, growing up, the curly hair thing was something I thought about more than talked about. My hair got curlier as I went through puberty, and all the people I was friends with had straight hair. I felt self-conscious about my hair. I felt like it was crazy, or I didn’t know how to make it look good. I used to set it in rollers so that the curls would be bigger curls. It was a way to straighten it, to make it, like, wavy. So I spent a lot of time preoccupied with that. Sleeping in rollers, being afraid of the rain.

Then I went to this camp that was really influential for me. It was where I started to write and paint and play guitar. It was this really open-minded environment, and the first week I was there I just started wearing my hair curly. Some mornings I would wake up, and I wouldn’t even brush my hair. It was this revelation to embrace how my hair was and not be trying to fit in with a certain crowd. I think from that point on it just became more part of an identity, where I liked that my hair didn’t look like everyone else’s.

I think subconsciously, a lot of my confidence or insecurity is related to my hair. But it was only through writing this and using these thoughts and feelings for these characters that I became aware. For some people their hair is a big part of their identity. How one’s hair looks and how one feels about themselves. It’s interesting how throughout the day there are moments of victory and pride, and then other ones of boredom and shame. There are other moments in the book about clothing—a certain object can give you power, and then the opposite, too. In the last few years I’ve been investigating the different emotional states and feelings about oneself that one has, even in an hour.

RH: I noticed that a lot in the book. These moments of confidence, where the character will think about how good her hair feels. It was an indicator of something, of things going well. If the hair is behaving then the world is okay.

RBG: Something so little as that can change your whole reality. How you’re feeling. Someone can wake up and have a pimple and feel subconsciously, throughout the day, less worthy and less capable because something has already gone not as they planned.

RH: It’s similar to tallness, in that it’s been a source of self-consciousness and then confidence. Except that it doesn’t change the way hair changes so quickly, you know?

RBG: [Laughs] Yeah, yeah.

RH: I mean, you can be having a good hair day, or you wake up and your hair’s one way and then it’s another way by the end of the day. Unless you’re putting on heels and changing height in that way, tallness doesn’t change.

RBG: And for you when you got to college and had all of these tall friends, you probably didn’t even feel as tall. Visually, you were standing out less.

RH: Yes! To the point where it’s almost a little uncomfortable when I’m around super tall people now. Because it’s like, “Wait a minute, I was supposed to be the tall one here!”

You mentioned was drawing covers and imagining covers, and this cover is so great. Did you have much power over it?

RBG: The artist who was working for Harper Perennial made this cover that was all-white with a photographic image of wavy hair, and for a long time it felt like that was going to be the cover. It was really slick looking. Then I was on Facebook one night, and there was a link at Juxtapoz Magazine that said “Erotic Art,” and I clicked on it, of course. There were these bold, black and white illustrations of women by Kaethe Butcher, this 24-year-old living in Germany. I forwarded some to my publisher, saying, “I know we have a cover but maybe if there’s ever a reprint we can consider these.” And he was like, “Oh wow, I really like these.”

I’m really into Photoshop so I just started playing around with them. The cover is actually from two different illustrations. There’s one of a woman smoking a cigarette, and one of a woman licking an ice cream cone. I arranged them so you couldn’t see what was actually happening, and I played around with the coloring for it. Because most of Kaethe Butcher’s stuff is black and white, and none of my characters had black hair. Harper got on board and paid her for the illustrations. It’s cool. The response has been really good for the cover. I had told myself that I wouldn’t have power over the cover and I had accepted it, so it was really exciting when I got to be part of that process. And funny how obstructing the figure and the ice cream cone, I feel like it ended up creating more emotional tension. Not being able to tell what these women are feeling necessarily.

RH: Totally. You can’t see either of their mouths.

RBG: Kaethe has a really great Tumblr. And hers is a really exciting spelling for Kaethe [pronounced Kathy]. I was calling her “Kay-th” for a while, but then a friend corrected me.