Mouthful is a monthly column about the author’s relationship with food, ten years into recovery from anorexia and bulimia.

I’m going to tell you a story that brings me shame. In 2013, I started modeling for artists to make ends meet. At first, I posed for drawing classes, which I enjoyed. I loved the smell of wood and paper, the skritch-skritch of pastels, the silence. I loved forgetting that I was nude. I loved how my mind wandered and returned to the present moment, then wandered again. I felt safe in drawing classes because there were procedures: I did short poses, then longer poses, with breaks between sets; I changed poses when the timer beeped; only the moderator was allowed to speak to me directly. I loved how the classes clapped at the end of my last pose to show me they appreciated my work. I was paid in cash, in a white envelope, which I put directly into my pocket. There was dignity in the envelope. It wasn’t a lot of money but I didn’t care because I liked what I had done to earn it.

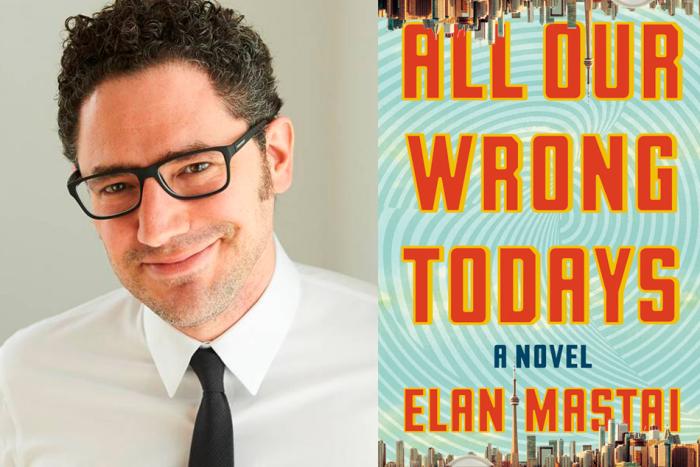

Soon after I began modeling for drawing classes, I was told that I could make five times as much modeling for photographers. The owner of the drawing studio warned me not to do it, that it could get sketchy, but I was poor, and this was a chance to make a lot of money. I made an account on Model Mayhem, “the #1 portfolio website for professional models and photographers.” I found two or three people that I knew on there, and reached out to the people who had taken their best pictures. The first people I posed for were friends, and friends of friends. Some of them paid me; some of them didn’t, but I liked them, trusted them, and respected their work. I felt it was earnestly art-focused.

Once I had a portfolio, I started booking gigs with people I didn’t know. I reached out to some; some reached out to me. For a while, I was able to book a paid shoot two or three times a week. I met photographers in studios and in their apartments and houses. I met a man in a hotel room in Jersey City. I met another at a bus stop in Bed-Stuy at six in the morning.

I had a vetting system that consisted of me emailing back and forth a few times with these men. They were always men. I asked the men what kinds of photographs they wanted and what they would use them for. Most of them simply posted them on Tumblr. Some of them showed their work in galleries. Some were fashion photographers who just felt like shooting that day. If I liked the work we did together, I would wait a few weeks and then try to book them again. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t.

It didn’t take me long to run through every worthwhile photographer in New York City with a portfolio on Model Mayhem. Money was tight, so I started taking on more questionable gigs. I had to eat.

*

One day, I received an email from a man whose Model Mayhem name included the word “Crucial.” He said he found me breathtakingly beautiful. He described himself as “an amateur/hobbyist,” “not very good but trying.” The few pictures he had on his profile were already a couple of years old, so I asked him if I could see his more current work somewhere else. I couldn’t. He liked taking pictures, but really only for his personal collection, he said, and a “future endeavor” he had regarding placing photographs throughout his home as conversation pieces.

My husband at the time and I were sharing a studio apartment that we struggled to afford. He had recently lost his job at a photography studio and my only other work aside from modeling was a part-time job at a bookstore paying just above minimum wage. One perk of the job was that I got to take home unsold pastries from the in-house coffee shop at the end of the night, which saved me from having to spend money on breakfast foods.

Crucial was asking to shoot nudes and erotica. I had done plenty of nude shoots and I figured I knew what he meant by erotica. When he asked me what my rate was, he used the words “hourly compensation.” I asked him for his legal name and for the names of three other models he’d worked with. I emailed one of them, who recommended him. His house was two subway stops away from mine. He said he would buy me breakfast or lunch. No other photographer I’d worked with had ever made this offer.

*

I went to his house on a Sunday morning. It was a three-story brownstone with a courtyard on a tree-lined street. I would soon learn that this was his childhood home and that his wife and son had moved out of it and gone to France.

He was stocky, with an Italian complexion, short, thinning black hair, and a light beard and mustache. As promised, he ordered me breakfast. I can’t remember what I ordered, but I recall that I only ate half of it. What I remember most clearly is that after I ate whatever I ate, I had to take a shit—and that I couldn’t shit, because Crucial’s only bathroom was connected to the kitchen, and to the dining room, where he sat while I sat on the toilet. And because the door of his bathroom was made of unfrosted glass.

I watched the back of his head through the door. He wasn’t looking at me, but I felt that he knew what I was doing.

I emerged from the bathroom still having to shit. We proceeded with the photo shoot. First, he turned on his TV and surfed to a music channel that was playing something like Journey, and turned the volume up. He used a silver plastic point-and-shoot camera similar to the one that we brought on family vacations when I was a child. All of the other photographers I’d shot with had used professional cameras.

I posed on his white leather sofas, on the floor, on the dining room table, on the half-wall bordering his stairs, on the stairs.

While I was posing on the stairs, he told me a story about another model he’d hired off of Model Mayhem, who turned out to be a sex worker. Her pimp had come with her and was supposedly waiting outside while they shot, but in reality had stolen all of the electronics from the basement apartment.

“Do you smoke?” he asked me abruptly.

“Sometimes,” I said.

“I want to get you smoking on the stairs.”

I said that I didn’t have cigarettes.

“Do you want me to buy you a pack?” he said, phrasing it as if I’d complained of not having one already. I didn’t know what to say to this.

So I said, “Really?”

I think this gave him the idea that I considered his offer generous. He told me to stay where I was and he exited the house, leaving me on the stairs. By this time, I no longer had to shit, so I waited, naked, on his stairs, as instructed.

He returned ten minutes later with a pack of Marlborough Blues, one of which I removed and smoked seductively while he took my picture from random angles. At one point, he tilted a standing lamp toward my face with his free hand, attempting to catch the smoke in the light.

“Let’s go to the bedroom,” he said.

*

There was a sculpture of a lion on the mantle above his bed, which he explained was identical to the one that had been in this house while he was growing up in it. It was his father’s, he said. He considered it a spirit animal.

There were tall, narrow windows with deep sills lining one wall. The walls were white or grey. His comforter was deep red or burgundy with gold detail.

He left the door open, which I realized with relief. I stood on a windowsill and he complimented my ass. He joked that the people across the way could probably see me, as if I would also find this funny. He complimented my ass again.

Then he told me to get on the bed, so I did. I knew that this was coming and had dreaded it somewhere in the back of my mind, a feeling that came to the forefront. On the bed, I posed in ways that flattered my ass because he seemed to like it and I wanted to speed things along. I turned over and around a few times, which he liked. He said other complimentary things to me as he circled around the perimeter of the mattress, testing angles. Then he told me to spread my legs.

“I’m not going to do that,” I said.

I felt the buzz go out of the room. This clearly disappointed him. “That’s what you agreed to do,” he argued. By the time he reached the end of the sentence, he was mad. I realized all at once that I was naked. He repeated what he said. The implication was that I was useless. That I had wasted his time. That the rest of the shoot was all leading up to this, and that I had blown it.

“I’m not going to do that,” I said again.

We looked at each other. I stayed lying where I was, unsure of what would happen if I tried to leave. I thought about the concept of cash up front.

*

Crucial ended the shoot soon after and we walked outside together. He handed me money, placing the bills directly in my hand and watching as I shoved them into my pocket. I asked him where the nearest café was, hoping that I could finally take a shit, and he insisted on buying me lunch. I didn’t want to share a meal with him but the rest of the shoot after the “incident” had gone as smoothly as could be expected, and we were now acting friendly. He had revealed many personal details of his life to me over the last three hours—about his job, his parents, his divorce, his new girlfriend and her adult son—and I surmised that he believed a degree of intimacy had been established, or expected, for his willingness to be vulnerable. Besides, he had already bought me breakfast—not everyone does that—not to mention a pack of cigarettes. Saying no to lunch would have hurt Crucial’s feelings.

Before we departed, he checked on his cats, which he’d locked on the ground floor with the TV on so they wouldn’t be lonely.

The café was on the way to the train station. We sat across from each other at a two-person table in the middle of the floor, which was blue. I ordered carrot soup. I was newly vegan. While we ate, he told me where he was going to go next: A third model he’d hired from Model Mayhem had become a good friend of his and she had recently moved into a storefront apartment with large front windows. She felt exposed to passers-by on the sidewalk, and he was driving her to IKEA to buy curtains. “If you ever need anything like that, you can just call me,” he said, back out on the street, looking me in the eye. “I love to help.”

*

Modeling stopped being fun when I had to do it. Financial desperation put me in a position that forced me to bargain with my body, but with no bargaining power. If I couldn’t book a shoot one week, I’d go hungry. I was forced to say yes routinely to projects that didn’t interest me, or people who made me feel unsafe, or who produced subpar images that I found embarrassing. I walked into each of these shoots knowing what I was doing and that I hated it, but needing to go through with it for the money. I had to feed myself and my partner.

I said that I’d tell you a story about shame. What I actually want to do is take this story beyond the point of shame. I’m a struggling artist in New York City. These are the lengths I’ve had to go to in order to feed myself.

Shame in this story comes along with the compensation I received for the socioeconomic demotion of my body when it wasn’t wearing clothes; when I wasn’t working on my own terms because I was desperate; I needed Crucial. Compensation for this demotion appeared not in the cash he paid me, but in the form of food, and other things to be consumed: breakfast, lunch, a pack of cigarettes. Carrot soup. Not money. It came as food to be consumed, with all of its compromises, its complications and conflicts. To stay alive, I ate it.

This is not about modeling, but about the unpaid work that women do, and the sacrifices we make for others even though they don’t deserve them; the favors; the cost of saving someone’s feelings in spite of our own; the way we swallow what we feel.

Food used as a weapon: an apology intended for the peace of mind of the apologizer rather than that of the victim; a way to make him feel better about traversing the line of female dignity; for looking down on her, down on me, and feeling guilty for looking down. It proves that he was aware. A gift may seem harmless, but it comes with heavy expectations. What I really feel isn’t only shame, but also fear. I allowed myself to be compensated for the fear that I felt on that man’s bed with another meal I didn’t want, which he forced upon me, which I agreed to eat even though I wasn’t hungry—had made enough sacrifices already on his behalf—but which I nonetheless consumed to save his pride. There’s the shame.

*

I recently started modeling again. So far, I have worked with one photographer, a good friend, without any money changing hands. Mostly, I’m modeling for drawing classes one or two times a week. I hadn’t done it since the end of 2013, when I started my last full-time job. I’m doing it now because it gets me out of the house and is immediate, untaxed cash in my pocket. It lends variety to my routine. It resonates with my writing practice in interesting ways. For instance, the lesson of yesterday’s class was that our eyes are the last tools we use to see; we see first with our mind, our training, and our prior planning.

The other day, I modeled for a three-hour, one-pose class. When I met the moderator, I got the sense that he was anxious about the fact that I would be nude. The factors contributing to my assessment are mingled with everyday misogyny, so it’s hard to explain why I thought this, but I’ll try: He wore a mild look of panic when our eyes met. He first asked me whether I’d posed before, and then, when I said that I had, proceeded to nervously explain to me how it’s done. When I assumed my pose, he asked me whether I was certain I could hold it for three hours. When he taped around my pose so that I could return to it after the five-minute breaks, he narrated what he was doing, as if unable to bear the silence. At the fifteen-minute break, he offered to buy me a cup of coffee.

After the class, I walked to a nearby café. I had a few hours to kill before another class I’d booked that afternoon and I wanted to do some writing. I sat at the bar and I spent a third of the money I’d just made on a fancy breakfast sandwich and a cup of coffee, which I allowed the bartender to refill continuously because I got the feeling that he liked taking care of me, and I wanted to be taken care of. I wrote in my journal about how a resistance meeting I’d attended the night before had had the reverse effect of leaving me feeling useless, and how much I just wanted someone that day to tell me I was valued. I thought about the concept of value, and how often and by what means I’ve had to seek it outside of myself. I meditated on the consequences of the compromises I’d made. I reminded myself that, although the cup of coffee the moderator had bought me had been a form of backhanded apology, the students in the class needed me.

*

I don’t have to be in the drawing studio now if I don’t want to be. I go because I like to be near people making art.

A few days after the drawing class with the male moderator, I modeled for another class moderated by the owner of the studio, who’d warned me years earlier about posing for photographers. She’s a nearly eighty-year-old woman who has been around the art world for decades and for whom I feel a special tenderness. She’s seen thousands of models come through her door and has appreciated each of them uniquely.

She operated the timer for the first half of the class, but at the end of the fifteen-minute break, she handed it to a student sitting near her and announced that she was going out for coffee. I had already assumed my next pose, but before exiting the room, she asked me if I wanted one, too. Unsure at first if I should breach my facade of immobility, I finally managed, “Sure, thanks.”

I was posing when she returned, so she left the coffee beside me, along with a banana. The class had begun early in the morning and I’d neglected to eat breakfast before I left my apartment, so I was starving, though I hadn’t told her that. She had just guessed. When the timer beeped, I put on my robe and sat on a wooden stool. I drank my coffee. I ate my banana. I smiled at the class, and the class smiled at me.

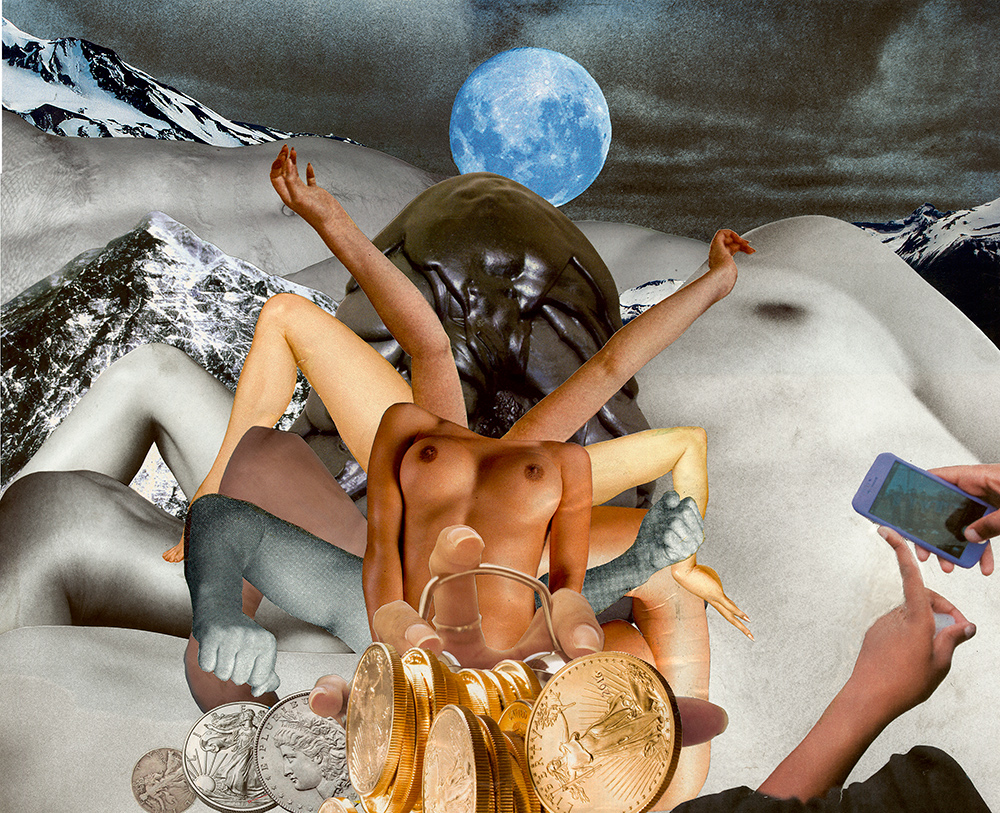

Collage by Sarah Gerard.