David Cronenberg’s debut novel, Consumed, bristles with miscellaneous Cronenbergia: obsolete diseases, damaged sex organs, arcane medical paraphernalia, a few plasticine penises, and, most memorably, a bug-infested breast, which one of the heroes of the novel conspires to have surgically removed in a subplot involving espionage, the Cannes film festival, and Kim Jong-il. It all adds up to a work of considerable audacity for a first-time novelist—though of course, as an artist, Cronenberg’s sensibility is already fully formed. The 71-year-old director maintains he isn’t interested in repeating himself, but it’s tempting, reading through this novel, to describe its familiar fixations as “Cronenbergian”—in its images and themes, you can plainly hear the echoes of the Canadian auteur’s career.

Consumed begins as a murder mystery. Celestine Aristiguy, a popular French philosopher modeled loosely on Simone de Beauvoir, has been found butchered and, indeed, partially eaten in her Parisian home. The chief suspect? Her husband, Aristide, the Sartre to her Simone, who has suspiciously absconded to Japan. Meanwhile, an unscrupulous young journalist named Naomi Seberg has taken it upon herself to solve the case on her own—and perhaps score a career-making interview with the killer in the process. But in typical Cronenberg fashion, circumstances are not quite what they seem, and soon Naomi finds herself embroiled in a dangerous—and thus all the more alluring—conspiracy that spans the globe.

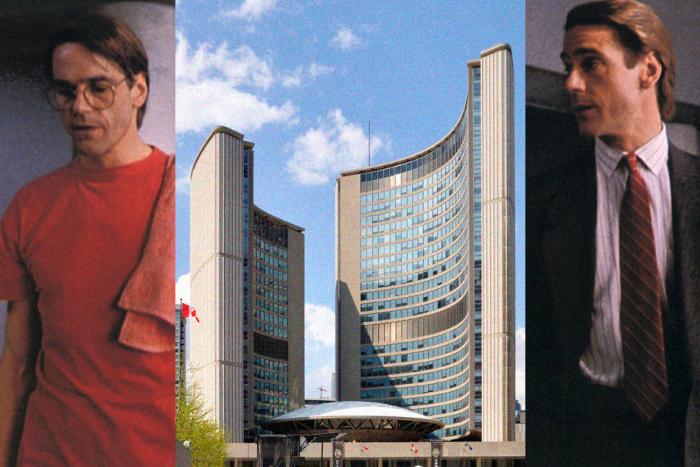

Last night, Cronenberg joined philosopher Mark Kingwell to discuss Consumed in depth at an event organized by PEN Canada. We had the opportunity to sit down with Cronenberg beforehand to talk about the totality of the body, the ubiquity of technology, and how an old screenplay for a sequel to The Fly invented 3D printing before the world did.

Calum Marsh: I saw a photograph online many years ago that I’ve been unable to shake from mind ever since. It’s of a woman’s breast, and it has been Photoshopped—I hope—to appear as though an infestation of small maggots or worms are emerging from within. I am aware, in the back of my mind, that the image is fake, but nevertheless I’ve always found it quite disturbing. And so as you can imagine I was surprised to find that one of the heroes of your novel happens to believe that her breast is infected with insects in much the same way.

David Cronenberg: No! I’ve not seen it. I’ve never seen that image. If you have it, you can send it to me.

What about that idea makes it simultaneously fascinating and repulsive?

There is a big difference with the insects in Celestine’s breast, because of course they don’t emerge—that’s part of the concept of it. But we like to think of our body as a kind of fortress, or a completely separate entity from the rest of the world. Of course it isn’t at all: the reality of it is that our bodies host billions of living creatures, in terms of bacteria and so on. But that’s a reality that is in contradiction to our idea of an identity that is based in the body—a body that’s very specific and clearly defined and separated from its environment. I think the infestation thing, as in so many cases, is a kind of tremor of a reality that we can’t deal with. We are a colony. Our bodies are a colony. Even our cells, our multicellular organisms, are combinations of many single cells that have found it more efficient to coalesce. For me it’s kind of a crude awakening to a sub-primal fear that’s based in reality—a fear of dissolution.

A reality that we need to ignore.

There are many realities we need to ignore in order to function. Whenever we’re reminded of that, however obliquely, it is very disturbing—there’s a real dissonance that’s happening there. But of course it’s part of the function of art to keep that dissonance happening.

I remember reading something about people who see their insides exposed, either through injury or surgery. Apparently seeing your body like that, without the abstraction of being whole, is incomprehensible.

Yep. That’s why my twins in Dead Ringers talk about how there should be beauty contests for the insides of bodies. You think of a beautiful woman, but if you think of the inside of that woman, would you be repulsed, would you still find her beautiful? Only a very few people have managed for whatever reason to develop an aesthetic of the totality of the human body, as opposed to the exterior of the human body. There are probably surgeons who think, Oh, that’s the most beautiful liver I’ve ever seen, or the most remarkable spleen, something like that. And that too is conceptually a conundrum for someone who has a philosophical bent of mind. How can we not have an aesthetic of the totality of our bodies? How can the insides of our bodies be repellent and disgusting?

You can understand that, of course. As a primitive assessment of health, you don’t want to see the inside of a body. Seeing the inside of the body means that death and disease are involved and it’s to be avoided, just like the smell of rotting meat is there to tell you to not eat it because it’s dangerous. This has always intrigued me. For me the first fact of human existence is the body, and in a sense it’s the only fact. That is our reality. That’s what we are. I don’t believe in an afterlife or a separate spiritual life, it is all one thing and it is the body. So that is something people also have to avoid thinking about because it involves thinking about mortality as an absolute end to one’s existence. That’s a hard thing for people to swallow.

One of the questions the novel poses seems to be the extent to which a part of your body can be not you. That is, if we are just bodies, to what extent can their parts be considered disposable?

Well, if you think about people who lose toes or even fingers, and how they deal with that… the first thing you do when you see your new baby is make sure it has all its fingers and toes. How separated are we from the reality of our body? And sure, people have to learn to live without certain parts of their bodies, and on the other hand there could be parts of your body that you simply reject it—you can’t accept it as part of who you are. It’s kind of a shocking concept, and it has neurological underpinnings—it throws into question identity: When you talk about “I” and “me,” what do you really mean?

Did you read that article in the New Yorker a few years ago about people missing limbs with phantom pain or phantom itches, and how that pain or discomfort can be relieved with the use of a mirror? A person missing their right arm, for instance, could “scratch” it by scratching their left arm with a mirror placed in such a way that it appears they’re scratching their right.

No, no, I hadn’t read that—that’s really interesting. You know, I had a grandmother who had an amputation because of diabetes, and she constantly talked about phantom pain. And the suggestion was that the brain hadn’t gotten the message that the limb was missing; the nerves were still travelling down and didn’t realize that they were truncated. I hadn’t read that article, but that would suggest that it’s more of a psychological thing than a neurological thing.

The only thing that goes directly on the screen is the dialogue and the narrative structure. You can be a terrible writer, but if you write good dialogue and have a good sense of narrative structure, you can be a good screenwriter and still be functionally illiterate, which a lot of good screenwriters in my experience are.

Shifting gears slightly, I wanted to ask about the transition from one medium to another. I think it’s safe to say that you have a mastery over film form, but here, you’re working in a new medium entirely. And so while in the novel you can see certain, shall we say “Cronenbergian” themes, they’ve been transplanted into literature, where you have no experience.

Well, it’s not a transplantation—it’s a brand new plantation. That’s how it feels to me. I was asked by a critic recently how my movies have influenced my novel. I told him I think he’d got it backwards: I influenced my movies and I influenced my novel. [Laughs] It’s not a transplantation, you see, because I don’t think in terms of themes: these are critical concerns. I can see some of those things and the connections, of course, but creatively that’s not how it works. It’s a post-intellectualization. I wasn’t thinking at all about my movies when I was writing this novel. Nor, when I’m writing a screenplay, am I thinking of older movies. I often have to tell film critics—and I’m not saying you’re doing this—that their process and mine are not the same. I don’t have a checklist of themes and images and metaphors. I don’t sit there and say, Gee, maybe this time I won’t go with the theme of transformation. [Laughs] You just don’t work that way.

In retrospect you could do an analysis from that point of view, but creatively, no. I really start with some characters, and some narrative ideas, and start to let them grow. And of course, it’s all coming out of my nervous system, so there are going to be some connections to other things I’ve done. Every time I do a movie it’s as though I’ve never made a movie before. I don’t have to put my stamp on it by insisting on certain things. I know there will be connections, and I don’t have to worry about them. And if I made a movie that nobody could tell was mine, then so be it.

Let me rephrase, then: When you are making a film, having made many films, you know based on experience how you might want to, say, shoot or stage or block an idea. This time you may have the same idea—character X talks to character Y or something—but you have to realize that idea with prose. You’re working with a medium in which you have no experience. Does that make sense?

Yeah, it does. Well, screenwriting is a very strange hybrid kind of writing. It’s not like prose writing—in fact, it’s better if your prose isn’t very good or deep. You’ve got a whole crew who are going to be looking at it for suggestions for an architecture that they are there to carry out. So you’re very restricted. You don’t bother to describe what your characters look like, for example, other than to say, you know, He’s handsome and he’s tall. An actor is going to be cast who might not look like that, so there’s no point. Likewise with locations and costumes. So it’s a very pared down, simple form, really, the screenplay. The only thing that goes directly on the screen is the dialogue and the narrative structure. You can be a terrible writer, but if you write good dialogue and have a good sense of narrative structure, you can be a good screenwriter and still be functionally illiterate, which a lot of good screenwriters in my experience are. Very different.

When you’re writing a novel, it’s more like directing a movie than writing a screenplay. You’re doing the casting, the costumes, the locations, the lighting. You’re responsible for creating characters in the flesh. It encourages different things from you as a writer. It’s much more intimate, and interior. You have to get inside the heads of your characters. You can’t do that in a screenplay. To me it’s always a pathetic thing when a movie based on a novel resorts to voiceover—you have someone reading the book to you like you’re a kid at bedtime. Even a bad novelist can immediately, convincingly put you in the head of a character. You can’t do that in a movie.

How did you arrive at your prose style? Did you have specific influences?

Ehn… I think not. I don’t mean to sound arrogant and say I’m devoid of all influences—of course you learn to make movies by watching movies and you learn to write novels by reading novels. When I started off writing, thinking I wanted to be a writer as a kid—which I did, I never thought about film at all—I felt really oppressed by the presence of Nabokov. I felt like everything I did was a kind of pastiche of his writing. When I started making movies I felt kind of free of influence—again, not because I hadn’t seen a ton of movies, but because the filmmakers I loved, like Bergman and Fellini and Godard, came from such a different place than I did that I couldn’t remotely be like them. So I had to invent myself as a director and I felt free to do that.

When I went back to trying to write a novel after all those years, I felt free once again to see what my voice might be. I didn’t feel I had an influence that was so oppressive or so influential that I felt I needed to struggle against it. And that was one of the exciting things about writing a novel for me: What voice will I have? What will my prose feel like, taste like? I don’t know what my influences have been. Saul Bellow is great, but I don’t write like Saul Bellow. Martin Amis is great, but I can’t write like Martin Amis. It’s partly because I can’t write like those guys that I feel like I’m not writing like those guys.

Your novel really has two prose styles, and two voices. It shifts, midway through, into the perspective of one character. The two feel very different.

Yeah, and so it should be. I felt like an actor. When I’m writing in that character’s voice, I’m speaking in his accent, and using his understanding of English—after all, he’s speaking English, but he’s not a native English speaker. I didn’t want to get too cute with that, but some of that is there—a little more formality and stiffness and difference of approach. His mentality is quite different from my quite neutral tone when I’m being the omniscient narrator. So for me that’s just good acting. I’ve read novels in which there are different voices but the writing is the same—to me that’s bad acting. It should be different. You’re in a different brain at that point.

What was the reasoning behind the shift? Obviously it’s quite functional, in that it reveals a particular backstory, but was there more to it than that?

No. It’s interesting, though, when I spoke to Rick Moody at a talk at the New York Public Library, he said that if you look at that section from a writing school point of view, it’s a very risky, high-wire kind of thing to do. I took that as a great compliment. At the time, though, I didn’t think of it that way—I didn’t think it was so risky. My impulse is to have a more uniform style and feel to a work, even in filmmaking. That’s one of the reasons I’ve never used flashbacks in my films—I feel it forces you to inject a completely different style into the middle of a film. I’ve never found a time in filmmaking where it was really justified or I wanted to do that. But here I felt I needed to hear from this character about his wife, and there was no other way to taste it. It wasn’t just the facts that had been missing until that point, it was also his relationship with Naomi, the woman who was interviewing him. The way that he tells her what he tells her is a sort of seduction—a confession, and an intimidation as well. So I could get all of that from this first-person monologue that I couldn’t get if I was getting that information from a more neutral, omniscient point of view.

I spoke to a colleague before I’d read the book, and he described it as a book that was written because it couldn’t have been done as a movie—at least not a commercially releasable movie. Were you conscious of being liberated somehow to do more on the page?

I was very conscious that I was doing things that I couldn’t do in a movie, or even think about doing in a movie—but that’s the sort of discursive intimacy that you can have. It’s weird. I’m not meaning to be dismissive here, but the book is like a compost heap: you can put lots of things into it and let them ferment. It’s a nourishing soil for other things. You can’t at all do that for a movie. It’s a completely different thing—more mechanistic, less organic. I did start writing this as a film. When I was asked what I might do as a novelist, I pointed to that. It was an idea for a film that had come to a wall. I like to romanticize it to myself by saying it was because it knew it needed to be a novel and it was waiting for me to realize that, and there’s some truth to that. I started to need a different form to realize itself. You could of course make a movie out of the book, but, as I’ve often said, you need to betray the book in order to be faithful to the book—it means reimagining it completely. But it wouldn’t do for you what the book does.

One of the reasons I’m sure I found the horror genre congenial is that it’s almost always focused on the body. The body is the center of all horror films.

It’s hard to imagine filming this book without showing, say, the crooked penis, or a breast being eaten. These are things that, on screen, even if you could get away with them, might seem distasteful, whereas on the page they don’t. Were these ideas and images you’d not been able to use previously that you now felt you’d found a home for?

Hmm, no, because once again, I don’t have a storeroom full of images waiting to escape. It all came to me naturally out of the characters and their concerns and the kinds of lives they live. That more than anything else is what I was doing. No, I just didn’t think that way: it would only be a question if I were wanting to make it into a movie, which I don’t. Though I would be happy to sell the rights for a lot of money to someone who did want it. In case you’re interested…

That was going to be my next question.

Good.

I wanted to ask you about the notion of technology. Books and movies about new technology often have an air of alarmism, but in the book you have the opposite approach: the mediating technologies, like Skype and iPhones, collapse physical space.

I’m thinking of it fairly neutrally as an observer. I see these things and I see that this is the way things are going. I do these Skype interviews—I just did one with Brazil an hour ago—and I can see that this is our current reality. I’m enough of a techno-geek that I enjoy a lot of it. But I’m really letting the reader have the reaction. I see these things as true and real, and I want to know what you think about them. I don’t have an agenda. I don’t have the moral high ground, or the techno high ground. I can’t say that this is a very bad place for the human race to be going, but I do find it all very intriguing and provocative, and I present it in a very neutral way. Then some people will say, God, I would hate for my children to grow up like this and be dependent on this stuff. Or, on the contrary, My child needs this, it’s great, if you want to be a part of the human race as it goes forward you have to be this and you have to come to terms with this. I have said, and I realize that it might be a strange thing to say, but I couldn’t have written this novel without the Internet. I really couldn’t.

At my age I love the compression of time and space that the Internet gives me, in terms of research. I love the ability of Google Earth to let me walk along a street in Tokyo, for example, without thinking about the possible dangers of plagiarism and all those other things we hear about. If it’s three in the morning and you need to do some research about that street in Tokyo, you don’t have to wait until the library is open and go and find that book—all of those things that not that long ago you would have to do. I’m sure it would have taken me two more years to write the book if I’d been writing it 20 years ago. So for me, the Internet, in terms of writing the novel, was a godsend. And undoubtedly some of that positivity has seeped into the book. At the same time, I can have Nathan criticize Naomi for not wanting to interact with the human beings she’s writing about—she’s happy just to go to YouTube and watch a few interviews with them to get a feel for their voice. So I can see both of those things, and they’re both true.

You briefly mention Naomi’s anxiety when she’s confronted with a name she doesn’t recognize and no way to quickly Google it. I like the idea that our intellects are constantly fed into by our access to the web.

Absolutely—I’ve experienced this. How do we absorb it? Is it a bad thing, or is this a supplemental thing? Are we actually expanding our brainpower and our nervous system, because certainly we’re absorbing the Internet into our nervous system—and I mean that literally, because as we know now, the brain is constantly changing. It’s not a static thing that reaches a point of no change. The neurons are constantly growing, and some of them are withering depending on how much we use them, and we are therefore literally incorporating the Internet into our nervous system, there’s no question about it. It’s a vulnerability: there’s a devastation if it’s not there, or if it was lost completely. It’s basically giving you super powers when it’s working. So you see the dangers and you also see the terrific power that’s involved.

The book posits Naomi as the most fully realized exponent of the Internet age. In some ways, that manifests itself as a weakness, in that she’s a less intellectual character than others. But it also has the effect of diminishing her ethics as a journalist. Do you think that’s a generational thing, or is it a product of the Internet?

I think it’s something that’s always existed, but the line is now much more easily crossed. The transgression can be almost invisible to the person transgressing—for young people who have grown up with the Internet as a total reality, something that was always accessible. Some people feel, and I certainly feel, that everything on the Internet should be free. Why would you pay for this stuff when it’s right there? Why are people putting up paywalls—what the heck is that? In the old days, no one would think that way. You would know that you were transgressing when you stole something or plagiarized something. But here, it’s almost common property, communal. It’s the ideal communist reality: everybody owns all this information and has access to it at any time. It has very much to do with the moment that we live in now.

I’d imagine that it’s harder to feel that way when you learn that, say, [Cronenberg’s new film] Maps to the Stars is available to download on the Pirate Bay.

Absolutely. You say, Well, it’s theft, there’s no question about it. It’s like the head of Apple saying that the Chinese rip-offs of the iPhone are not flattery, they’re theft. And you have to sort of think that as well. I know for a fact that some people have downloaded Maps to the Stars and watched it for free—people I know. And I want to say, Hey, you just robbed me—you stole money from me.

On the other hand, I know that if it weren’t for illegal downloads, I wouldn’t have discovered many of your films.

Well, sure. I remember when I went to China to shoot some of M. Butterfly, I was happy to learn that they were selling bootleg copies of my movies there, because it was the only way they could be seen. There were people who knew my films there, but only because of the illegal bootleg copies of films that would have been suppressed by the government. Same with Cuba: There was a time people were telling me that my films were known in Cuba, despite them having never been released commercially there. But they knew them. You have to say, under those circumstances, that I’m all for that theft. It’s a blow for freedom. [Laughs] And you say, Well, none of these things are very clear-cut. It’s hard to come up with a formula that’s universally applicable. There are all these strange subtleties involved.

Especially with movies, it seems, because so many things go out of print. I know that many of your films are unavailable on DVD.

I’d rather have my movies exist illegally than not exist at all. Sometimes it comes down to that. In my case, it often comes down to that. [Laughs]

Shifting gears again, I wanted to ask you about the 3D printer that comes into play in the book. I was reminded of the 3D printer at the TIFF exhibit of your work last year…

I had written most of the novel by then, but it just made sense. It was obvious that it was a technology that was coming on like an express train—it wasn’t going to stop. And it was going to manifest itself in all kinds of intriguing ways, including printing human organs, which I don’t quite get into the novel. But it wasn’t the TIFF thing that induced it. I had been intrigued by the whole idea as soon as I was aware of it.

It’s kind of a perfect fit with your work. I’d read about a 3D printer that could replicate a working gun, which made me think of the fish gun in eXistenZ.

Right, yeah. I even wrote a sequel to The Fly quite a few years ago in which I was positing the downloading of physical objects. The way I had conceived of it was a bit different than 3D printing, but it was basically the same idea. You’d have a sort of a big microwave, and you’d order something from Amazon and it would appear, physically, in this microwave oven—it would somehow be transmitted. And really, 3D printing is the real-world version of that. So I feel I actually invented 3D printing. I wish I could copyright it, but I missed that boat.

I find it fascinating in relation to your work—and don’t take this as a suggestion that you are consciously copying yourself or something. But your older films had a kind of physicality and tactility that your later films do not. Now you work in a cooler register—cooler and more digital. But what’s cool about the 3D printer is that it’s hyper-new and digital, but also fundamentally tactile—it creates physical objects.

Mmhmm. That’s an interesting observation. I can’t say it was calculated. One of the reasons I’m sure I found the horror genre congenial is that it’s almost always focused on the body. The body is the center of all horror films. But at a certain point I felt I had done that, and I was starting to be intrigued by other things. Even Dead Ringers, though concerned with the body, is not really exactly a horror film. For me this is all natural. It’s intuitive and organic and doesn’t require that analytic thought—but that, when applied, will certainly show many of the connections you’re describing, I can’t deny it.

In the world of literature it seems more appropriate to talk about a book in terms of themes and intentions, these analytic things you’re mentioning, whereas a horror film may not invite that kind of scrutiny for serious people.

Well, we’ll see—there are some out-and-out horror novels that are serious. It took people a long time to apply serious analysis to Stephen King’s work. And part of that has to do with attitudes people have toward genre, which I think is misplaced. You can have really intelligent horror films and really stupid family dramas, obviously. But I think it’s all about language, really—it’s about the articulation of prose that encourages that. When you're being analytical you need language. A film can be very visual, very visceral, and not involve language at all—just dialogue, which can be simple. It’s harder to discern a film’s intellectual implications. In a novel, because it’s language, it’s the same abstraction, the same tool you use in your analysis. That’s one of the reasons that it feels like more of a comfortable fit.

The novel is quite clearly literary—seriously literary. Whereas when your first films were released, it would have been easy to dismiss them as unserious because they were genre films.

There was definitely a sense that low-budget horror films are to be enjoyed partly for their badness. Bad effects, bad acting. It was a whole geeky thing, that fans of the genre would like it if it were corny and bad. And so I thought that people were imposing that on my early movies. Even Shivers, which I was doing with a very limited budget and very limited technique because it was my first movie. But as a writer, my intentions were serious. For me, I was always making art that was serious. Serious art, of course, doesn’t mean that there’s no humor, because all of my movies are funny, and I think my novel is funny, too. But it was part of the enjoyment of the genre for people to think, for example, that the acting was bad. The acting wasn’t bad. I was serious about my actors and directing them from the beginning. That has gradually become recognized; now, people say that Cronenberg is good with actors and people love working with him and so on, but it wasn’t always like that. So it’s part of the perception. If Consumed were placed in the ghetto of sci-fi or horror I would be facing the same kind of dismissive attitudes. It’s something anybody who has worked in that genre has to face. Even though we know that there are books that can be considered part of that genre that are brilliant works.

I liken the book more to, say, Ballard than Stephen King.

Yeah, yeah, and even Burroughs, who wrote a kind of sci-fi, in a way, with Mugwumps and so on, and his giant Venusian insects. It’s something anybody who has worked in that genre has to face. Even though we know that there are books that can be considered part of that genre that are brilliant works. But you’re always fighting that stereotype.