For much of the night, six of the seven chairs onstage at the New York Review of Books’ 50th Anniversary celebration at Town Hall, on 43rd Street, remained empty. Bob Silvers, a founding editor, often sat in a seventh, watching over his presenting contributors. It was hard not to find heavy, if perhaps unintentional, symbolism in the empty chairs. Other than Silvers and Jason Epstein, nearly all of the other founders of “the paper,” as some of them referred to it, are dead: Barbara Epstein, Elizabeth Hardwick, Mary McCarthy, Robert Lowell, Norman Mailer. Silvers himself seems sprightly and all but it’s always sad to contemplate what it might be to find yourself the last one standing.

The nearly full house that turned up to watch the roster fit what you’d expect. Parul Sehgal, a New York Times Book Review editor, tweeted, “Holding it down as the only person of color who’s not an usher at the #NYRB anniversary. I’ll totally help you find your seat though.” The age spectrum was slightly better represented, if tipped toward the high end. I will go ahead and credit the under-50 turnout largely to Joan Didion, who was the evening’s star attraction and first presenter.

Silvers came out to much applause and gave a standard run-down of the Review’s founding, in 1963, during a newspaper strike. Everyone who wrote for the Review, in that first issue, wrote for free. They were given what no doubt sounded to Silvers like the tight deadline of three weeks. I wanted to reach out to my blogging friends in the audience and remark on how we’d often kill for a three-week lead time. He cites, as its animating philosophy, an essay Elizabeth Hardwick once wrote for Harper’s, which made one of those claims about the long decline of book reviewing: “A book is born into a puddle of treacle; the brine of hostile criticism is only a memory.” The Review set out to sour the puddle, as it were.

Sharp words notwithstanding, it had occurred to me outside, waiting to be let into the event at the hour it had been appointed to start, the pipes clogged by unusually strong security no doubt associated with the Scorsese cameras that were filming the affair, that I had no idea what I was expecting from this performance. People who spend their lives among books do not go in for conga lines, or even for public speaking. Didion herself is legendarily flat, in person, in a way that has an intrigue of its own. All those mellifluous sentences, read in monotone, has a way of puncturing certain illusions about her—specifically, that she is as comfortable and elegant in the world as she comes across in the prose. For me that’s comforting, proof that I don’t have to cultivate the perfect life for the perfect sentence, but others might disagree.

It turns out they are simply going to read things to us. Didion emerges first, looking, not to be too blunt about it, unusually frail. She was enveloped in an enormous grey sweater, and dark mukluk-type boots, which is the most casual outfit I’ve ever seen her wear, and was helped to a desk by stagehands. She simply read a piece she’d written years before, on the Central Park Five, the young black men who were accused, convicted, imprisoned, and later exonerated, of a brutal rape in the 1980s. She halted and stumbled several times. She carried what looked like, though she never used it, and I was in the nosebleeds so can’t confirm, a large magnifying glass. Several cell phones manage to go off in quick sequence as she’s reading, but I can’t tell if she hears them. And when she is done, she stands up unsteadily, and is escorted back offstage.

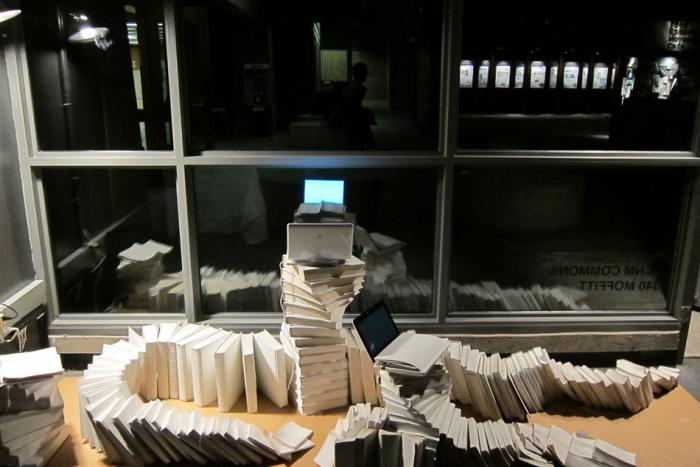

This ritual repeats, if in slightly more energetic form, with six more presenters, possibly a few more than the audience was prepared to see. The novelist John Banville says some nice things about how the Review has not relied on “big names,” which provides an interesting lens into which names consider themselves big and which do not. Mark Danner, a political journalist, tells tales of a time when the offices of the Review could be “charitably called Dickensian,” conjuring images of paper towers with cigarette smoke rising behind them. Mary Beard, a classicist, emerges onstage in a fabulous gold-sequined cardigan, paired with flowing grey hair out of your wildest dreams, and lists all the references, good and bad, to the ancient Greeks and Romans in the Review. (The not-subtle implication is that this is one of the last places in which such references are to be found, of course.) Daniel Mendelsohn holds forth on the aesthetics of Zero Dark Thirty, and Michael Chabon, the only real performer in the bunch, does a nice dramatic reading of a piece about writing his first novel, and is the great crowd pleaser that closes off the long night.

But the presentation which strikes me as the most affecting comes from Darryl Pinckney, a name you might not know if you are not a longtime Review reader. He describes his engagement with James Baldwin, the great essayist and novelist. For a long time he’d avoided a lot of Baldwin, he said, because Baldwin wrote about race, a subject Pinckney intended to “put off as long as possible.” But he ended up writing an essay on Baldwin’s last novel in the Review’s pages, a piece in which Pinckney wrote with a self-conception, as he himself described it, was that of “Mr. Important Little Shit,” who could call out every bit of the great writer’s sentimentality. Pinckney described holding on to that attitude for years, even seeing Baldwin at a party once and, in a “seizure of self-importance,” asking the great writer about it. When Baldwin was graceful enough to claim he’d never read the review, Pinckney offered, drunkenly, a few of his arguments. And Baldwin’s smile, Pinckney said, “was all forbearance.”

In other words, when you are young, that kind of review, the kind that takes down someone great and important, the kind that is “harsh” and “honest,” might seem like a good idea. But when you are older, even if you’ll be on a stage celebrated for being one of the last truly intellectual publications standing, it’s possible you will regret a harsh review or two.

--

Photo of Barbara Epstein and Robert Silvers in 1963 by Gert Berliner/NYRB.