A Visit To Macondo, by Alberto Manguel

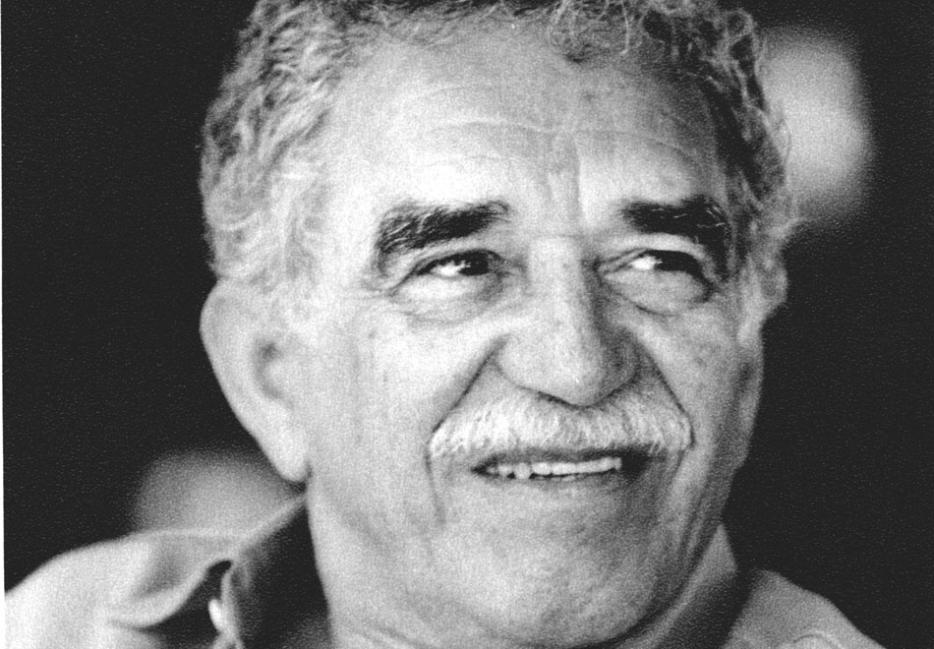

I met García Márquez in 1969, in Barcelona, when he kindly granted me an interview for an Argentinian magazine in order to allow me to make some money to live on. García Márquez knew what it was like to be a young penniless writer. When, after finishing One Hundred Years of Solitude in 1966, and being rejected by the publisher Carlos Barral in Spain, who said to him "I don't think this novel would sell," García Márquez decided to offer it to Editorial Sudamericana in Buenos Aires, but had to send the manuscript in two parcels because he had not enough money to pay for the postage at all once.

By 1969, he had proved Barral woefully wrong and was making more than enough to live on. He had started to write the novel that he would publish six years later under the title of The Autumn of the Patriarch and was amusing himself (he told me) by inventing proverbs that would fit the character of the aging dictator. "In the coop, the chicken on the top roost shits on the chicken on the lowest one." "The hands complain that the feet never work." He would laugh loudly at these, but ended up not using them in the book.

We talked about reading. He was a voracious reader, though he confessed that his literary education came from bad poetry and Marxist books that his history teacher lent him on the sly. Faulkner was his idol, and works as different as Sophocles’ Oedipus and W.W. Jacobs’ horror story “The Monkey’s Paw” taught him (he said) to build narrative structures that were credible and fantastic at the same time. He confessed that the first pieces published in the Barranquilla newspaper of his youth were signed with the name Septimus in honour of the deluded character in Mrs Dalloway.

I had read him in my adolescence, in the slim pocket editions of his early novels published by Angel Rama in Uruguay. But by the time I met him, he had become famous. Accepted by Sudamericana, One Hundred Years of Solitude had been an overnight success. I remember that three friends called me up the morning after the publication to tell me what an extraordinary book it was and to make me promise I would go out and buy a copy. And yet, in those days, a book celebrated in South America was not any less unknown elsewhere in the world: it required the mysterious combination of an English-language audience and the academic nihil obstat to grant a South American book the status of a modern classic. Only after Gregory Rabassa published his translation in 1970, García Márquez's began to be touted for the Nobel Prize he won in 1982.

García Márquez first imagined the village of Macondo in the early fifties, after a visit to Aracataca with his mother, and made it the setting of a story, "A Day After Saturday," published in 1954. Macondo is the spiritual incarnation of a particular area of Colombia, truer to the spirit of the place than Conrad's Costaguana (another, earlier imaginary version of the country). Macondo belongs to the geography of imaginary places not because it is unbelievable, but because it follows its own rules of reality. A few years ago, the prime minister of Australia declared that an island off the Australian coast no longer had political existence because, in order not to deal with a boatload of refugees that had landed there, the Australian government had decided to re-draw the borders of its territorial waters in order to exclude it.

The creation of Macondo proceeded in exactly the same manner, but in reverse, when (García Márquez tells us) it decided to cut itself off from the history of the rest of the world, an inland island redefining its own space and time, and even, when threatened with collective amnesia, reasserting its own language by labelling each tree, each piece of furniture, each cow, with a card that said "This is a tree," "This is a chair," "This is a cow, it produces milk, with the milk we make café con leche." To the epistemological lies of the real world, Macondo opposes its confident truth, which is not found on any map. "Real places never are," remarked Herman Melville, another of García Márquez's literary heroes.

For a writer who sided with the revolutionaries of Latin America and stubbornly professed his admiration for Cuba and Fidel Castro, García Márquez was surprisingly uninterested in the fiction of documentary social violence that runs like an incandescent thread through the works of contemporaries such as Vargas Llosa (who has never shied from professing his contempt for his Colombian colleague). "I'm not interested in acts of violence themselves," García Márquez told me, "but in the threat of violent acts." This threat is perceptible in all of his books, especially in those that chronicle the long century of Macondo. The history of Macondo is greater than the particular histories of Latin America, because, like a secret mirror, it holds them all.

Alberto Manguel is an Argentine-born Canadian writer and author of many non-fiction titles including All Men Are Liars, and The Dictionary of Imaginary Places.

*

On Gabriel García Márquez, by Randy Boyagoda

One Hundred Years of Solitude is the most important airport book I ever bought. That you could even buy a 40-year-old Magic Realist magnum opus set in South America while passing through a 21st-century airport in Singapore testifies to Gabriel García Márquez’s distinctive greatness. His readership contained multitudes. There were admiring writers and critics and scholars and students, yes, not to mention dictators and presidents and other politicos. But there were also ordinary readers, that rarest of types for a major literary novelist to appeal to, the sort that’s simply in search of a great story to lose themselves in for a while—say, for the duration of a flight.

Thanks to this expansive appeal, I was able to pick up a copy of One Hundred Years a few years back, on a layover in Singapore en route to Sri Lanka. I was going there to research a novel I was working on at the time. I abandoned that book and wrote another, Beggar’s Feast, which only exists today because I read Marquez on my way to the island. That’s not because I came anywhere close to conjuring the fullness of family and world and time that we encounter across the generations of the Buendía clan’s life in Macondo. Rather, it’s because of how reading Márquez taught me to listen to the world around me as a writer and as a little boy at the same time. Reading Marquez taught me that the very best of stories come to life when you listen both ways at once.

For decades, Marquez pointed to two major sources of inspiration and influence: his reading and listening. In reading terms, it was William Faulkner—specifically, the ways in which Faulkner explored the tragic depths and strange far reaches of human experience within the confines of tiny, out-of-the-way places, set largely in the decrepit homesteads and rotting plantation houses and sleepy town squares of a rural Mississippi county that he called Yoknapatawpha. Just as important as reading Faulkner was to his formation as a writer was Márquez’s listening to stories told to him by his grandparents and two aunts, who raised him in the small Colombian town of Aracataca in the 1920s and 1930s. From them, he heard stories of war and destruction and massacre, of famous romances and family feuds and blood grudges held for whole lives, even generations, and it all happened right there, in their town, with their people, his people.

If you’ve read One Hundred Years of Solitude, or Love in the Time of Cholera, or The General in His Labyrinth, among his many works, you’ll know right away that Márquez could never have written these books were it not for his listening to those family stories and for his reading Faulkner, for reading Faulkner and remembering those stories, and in both cases discovering that what they involved had everything to do with how they were told. Indeed, Henry James showed us how to look at the world, as a writer; Proust, how to remember; Flaubert, how to find just the right word. But Marquez showed us how to read and how to listen, which was just as much who to read, and who to listen to, and why we need to do these things, together.

I read Marquez on my way to Sri Lanka and while I was there, too, which led me to listen to family stories from uncles and aunts and my grandmother in a very different way on that visit. I came back to Toronto with a whole new novel in my head thanks to him. More so than any other writer in our age, he showed us how to be liberated from the dead letter confines of literary influence and from the emotional hothouse (or boring purgatory) of family history by bringing these incompatible realities together and making of them a whole new world for millions of readers to escape into. These escapes took place in presidential palaces and university dorm-rooms and airplanes and, for me, ultimately, in the musty humid guest-room of a house full of old family secrets in Sri Lanka, where One Hundred Years of Solitude became the best possible guidebook.

Randy Boyagoda is the acclaimed Canadian author of Governor of the Northern Province, which was nominated for the 2006 Scotiabank Giller Prize, and Beggar's Feast. He currently teaches at Ryerson University as an Associate Professor of American Studies.