Early on the morning of February 20, 1976, two police officers approached a green Camaro parked at a rest stop near Pompano Beach, Florida. Inside, Jesse Tafero and his partner Sonia Jacobs were sleeping, along with Jacobs’ two young children. Tafero’s friend, Walter Rhodes, was asleep in the driver’s seat.

Exactly what happened next remains unclear. What’s certain is that one of the patrolmen asked the two men to step out of the vehicle, shots were fired, and both officers were killed. Tafero, Rhodes and the family tore down the interstate in the stolen police car. When they were stopped at a roadblock, the gun used in the shooting, which was registered to Jacobs, was in Tafero’s waistband.

Rhodes immediately struck a deal. In exchange for a lighter sentence, he testified that Jacobs and Tafero were solely responsible for the shooting. The couple, meanwhile, insisted that Rhodes, who was on probation, had panicked, shot the officers, and then given Tafero the gun while he drove away. Someone was lying, but with little physical evidence, it was difficult to know which story was true and which was false.

The jury decided Tafero and Jacobs were the liars. Both were sentenced to death. In 1990, Tafero was killed in the electric chair, a gruesomely botched operation in which the executioner had to turn to the power off and on three times in total while flames arced off Tafero’s head and the smell of burnt flesh filled the room. It took him seven minutes to die.

*

Picking out lies is a vital skill in the criminal justice system, but the fact is, we’re bad at it. While law enforcement professionals are confident in their ability to tell a true statement from a fib, studies have found that they’re actually no better than the average person. In controlled experiments, they were able to tell whether a story was true or false just 54 percent of the time—barely better than flipping a coin.

Over the years, there have been plenty of attempts to create tools and methods to help detect deception. Lie detectors and other approaches that depend on physiological responses have been promising, but problematic. After all, both liars and truth-tellers can have the same physical reaction to questioning, acting nervous as they worry about being disbelieved, thinking hard about what they’d like to say next and how they’d like to present themselves.

A different tack is to analyze the statements themselves, without relying on a witness’s presentation. Is there something measurably different about a truthful statement compared to a lie? It’s a tantalizing idea. If you could break down a story into its basic components—the contradictions and backtracking, the expressions of emotion, the amount of time spent reproducing past conversations, the level of detail—would you be able to find something in its DNA that could help you determine whether it was true or false?

One strategy, recently developed by psychologist Siegfried L Sporer, is called the “Aberdeen Report Judgment Scales.” The ARJS uses ideas from forensic experts and, according to the literature, integrates those approaches with “theorizing from autobiographical memory, attribution theory, and self-presentational strategies.” It’s basically a massive checklist, with 52 items you rate on a seven-point scale, the different sets of criteria sorted and weighted based on importance. Did the statement contain superfluous detail? Were there spontaneous corrections in the telling? How would researchers rate its clarity and vividness? The idea is that, instead of just taking a holistic view of a statement and deciding whether you think it feels true or false, you break the statement down into its constituent parts. The hope is to bring a little rigour and quantitative objectivity into the murky world of lie-detection.

In past studies, the ARJS has delivered promising results, but cases like the Tafero murders can be particularly difficult to assess. In Tafero’s case, both he and Rhodes admitted to being at the scene of the crime. There was no need for either of them to pretend they weren’t there, feign ignorance, or create an alibi. All the killer needed to do was explain what happened, include as much detail as he wanted, then transfer authorship of the act to the other man.

In a recent study, published in the prestigious American Journal of Psychology, Sporer attempted to test whether the ARJS could be useful in these types of hard-to-detect cases. Participants were asked to tell a story about a time they’d committed an immoral or illegal act. Half the group was then asked to change the story so that they were innocent and another person was guilty, creating a false accusation.

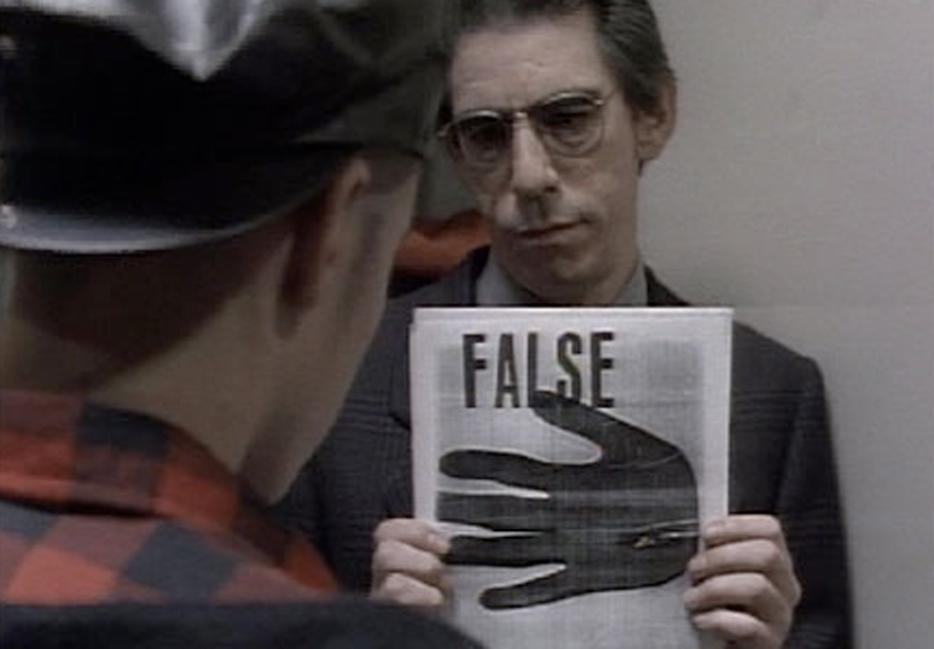

The statements were recorded and transcribed, then sent to “raters” trained in the ARJS for evaluation. The raters went through each story and marked them. In the end, scores were tallied up and judges gave each story a number from one to ten, with one being “false” and ten meaning “true.” They also had to indicate how confident they were on a ten-point scale.

The experiment showed, in short, that detecting lies remains incredibly difficult. The ARJS didn’t improve things in the slightest. The control group, people off the street who judged the statement without any instruction, performed almost exactly as well as the carefully trained ARJS raters. In a second, related study, the researchers did find that people trained in a shorter version of the ARJS that only accounted for the most predictive criteria did a little better when it came to assessing whether a lie was true or false. When asked to judge a true statement, however, they reverted to mean.

The study doesn’t offer much hope for unlocking the secret to detecting deception. Confidence, the researchers found, had no bearing on accuracy. It didn’t matter how sure you were—you were able to judge a liar just about as well as a flipped coin.

In the case of Tafero, it’s possible the coin flipped the wrong way. Two years after his execution, his partner Jacobs was released due to lack of evidence. Rhodes, meanwhile, recanted his testimony. He said that he, not Tafero, had pulled the trigger. The case has become famous among anti-death penalty advocates decrying wrongful executions.

Since then, Rhodes, who was released in 1994, has recanted his recantation. The truth of the case remains murky, impossible to access. Was Rhodes lying when he said his friend shot those officers? Was he lying when he recanted? Is he lying now? The best that science can tell us, so far, is that it’s very difficult to know.