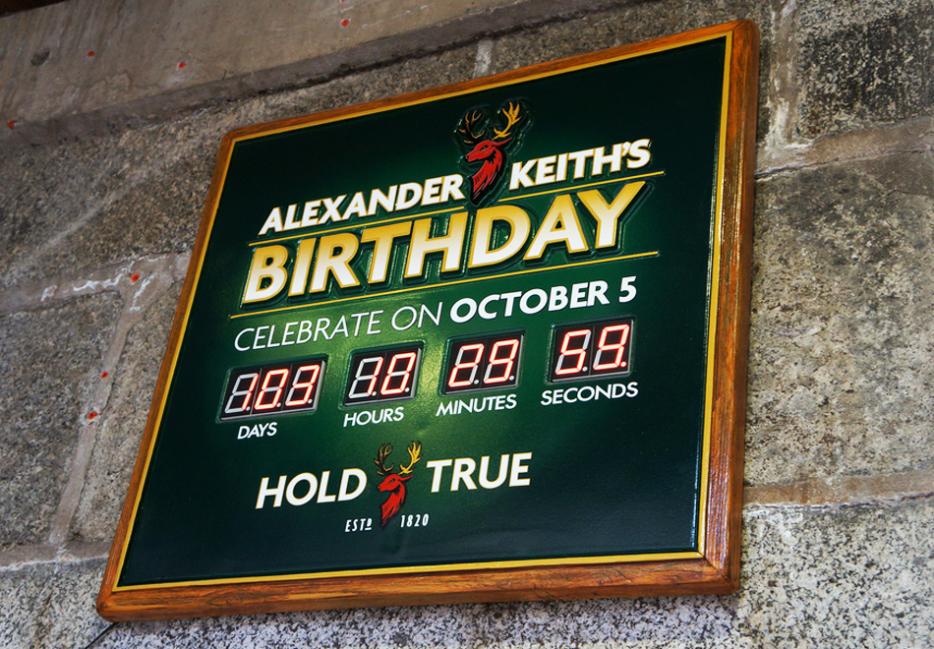

Depending on how often your local replaces its beer swag countdown clocks, you might not have been aware that this past Saturday was the birthdate of Alexander Keith, namesake of the beer your ponce-ier friends have already begun explaining is not actually a pale ale.

The countdown to Keith’s 218th birthday was one of the more forward-thinking ad campaigns the brand—which now spends its money pitching hops (ponces: a growing beer market!) and fake indie songs—has come up with. Aiming for the history angle just a few years before everyone started canning things, in the early-to-mid-2000s, it put Keith’s distinguished lineage front and centre: The man, after all, was a mayor, member of the legislature, and benevolent patriarch of the Scottish diaspora in Halifax. With the big breweries having already outgrown their family names—Keith’s has actually been owned by Labatt’s since 1971, but wasn’t available nationwide until 1996—leaning on Keith was a reasonable move, a way to stoke patriotism without directly challenging Molson’s Joe Canada shtick.

At the time, that was also roughly the tactic employed by the flagship brand of Guelph-based Sleeman’s, then as now the third overall largest brewer in the country. The modern incarnation of the brewer was actually founded in the late ‘80s, but since Deloreans and Nintendos presumably did not yet have the suitable nostalgic pull, it emphasized the recipes that the original John Sleeman and company had brewed from 1834 to the company’s forced closure in 1933.

Sleeman’s still sells its history these days, although it has since decided to narrow its focus on that shutdown. As you probably don’t need reminding, since the company is doing such a great job of it, the brewer used to make some of its money by bootlegging during Prohibition—it was a meeting with Al Capone that led to its shuttering.

Though the criminal link no doubt helps beer drinkers across the country pretend they’re doing anything more interesting than groping around for a slight buzz, meeting with Capone isn’t actually the most interesting thing a close Canadian relative of a brewer has done, nor remotely the most criminal. No, for that, we have to go back to our life-toasting civic stalwart.

While he remains sadly unremarked upon by the company literature—they might be a bit sensitive about the whole criminal angle—Alexander Keith’s close relative, Alexander Keith Jr., is our most blatantly law-breaking brewing family associate, the type of guy who makes rum-running with Al Capone look like lawn bowling with an English aristocrat.

For a start, Keith Jr. is actually Alexander Keith’s nephew, not his son; he took on the suffix in his adult life, when he figured it was a good idea to emphasize the connection to his rich mayor uncle. He would later become known as The Dynamite Fiend—also the name of the biography based on his life by Michigan professor Ann Larabee—but we’re getting ahead of ourselves some.

He took his first step toward earning that nickname when he blew up an armory in Halifax, a fairly drastic measure designed to cover up his initial crime: shortchanging and skimming from railway companies who were using him to procure their gunpowder from said armory. Though years later Haligonians would say they always knew it was him, at the time his connections and some supposed under-the-table payments from that rich uncle of his kept him out of trouble. Keith Jr. would hold off on the dynamite for a while after that, finding slightly more honest work at his uncle’s brewery before settling into the then-lucrative business of aiding the Confederate States in the U.S. Civil War.

In fairness to Keith Jr., in Halifax at the time, supporting the Confederacy wasn’t quite the heinous, Skynyrd-soundtracked act we think of it as today. Though slavery was abolished in what’s now Canada in 1833, Britain, which still ran the place, needed the South’s cheap cotton for its textile industry, and some overzealous Union excursions into Canadian territory, mostly while trying to apprehend Confederate criminals, had turned a large chunk of public sentiment against the North.

Now, in fairness to the rest of Halifax, few of them did quite as much to help the South as Keith Jr. His major (and quite profitable) business was blockade running—organizing ships to get supplies in and out of the South. But he also helped a Confederate pirate escape capture during the Chesapeake Affair, and participated in a plan to try to infect Northern cities with yellow fever by shipping them clothes and blankets believed to have been infected with the disease (they didn’t know at the time that mosquitoes were the main source of transmission). He also helped organize the shipping of supplies for John Wilkes Booth during an early plot to kidnap Abraham Lincoln.

Keith Jr., of course, actually also worked to foil that last plot: after taking out an insurance policy against the ship the goods were travelling on, it’s believed he had the ship sunk—probably with dynamite—so he could collect on it. This is believed because Keith went on to make a habit out of screwing over his associates, Confederate and otherwise, by, at least in part, taking out an insurance policy on the lives and ships of a counterpart in Montreal, convincing him to sail with them to the South, and then sinking them—probably with dynamite—once they got out of the St. Lawrence seaway.

Your average murderer and war profiteer might have stopped there, but you do not get nicknamed The Dynamite Fiend because you have only a casual interest in blowing things up. For his final act, Keith Jr.—who, for perhaps obvious reasons at this point, fled to Europe and lived under an assumed name after the war ended—planned to pull his old insurance scheme on the German passenger liner Mosel, sinking it, with dynamite, in the middle of the ocean. Due to a loading error, though, the bomb went off too early, killing more than 80 people and wounding at least 200 on the docks at Bremerhaven. Keith Jr., who witnessed the incident from a nearby ship, was apparently so overcome by what he saw that he went to his room and shot himself; he died five days later, after giving a partial confession.

Keith Jr. is not, for obvious reasons, much a part of the Keith family legacy. There is, however, at least one weird concordance between the beer we know and the terrorist we don’t. For his last bomb, Keith Jr. commissioned a timing mechanism that was purported to be the quietest such piece of machinery yet made, one that helped it remain hidden among the luggage: a nearly silent countdown clock.