Chapter One

“It’s strange how you remember certain things and forget others. If, all of a sudden, we remembered everything that we have forgotten and forgot everything that we remember, we would be completely different people.” — Michelangelo Antonioni

On June 8, 2018, after hours of driving under the sweltering Andalusian sky, leaving behind the haunting grandeur of Granada, the stubbornly snow-capped Sierra Nevada mountains framing the horizon, I had just reached the outskirts of Almería when the news of Anthony Bourdain’s death came on the radio. The Mediterranean Sea had just come into view, where out beyond the strange pale expanse of the “Mar de plastico” (Sea of Plastic), 20,000 distant greenhouses spread out over the desert coastline like the shattered pieces of a broken plate, shielding millions of tons of citrus groves, nuts, and vegetables.

When they mentioned Bourdain was found inside his hotel room in Kaysersberg, France, I turned off the radio, then pulled over at the next gas station to buy a pack of cigarettes. After three months on the wagon—my longest stretch in years—my nerves needed a crutch for the remaining fifty-mile drive to my destination in Vera, Spain.

I remembered the former chain-smoking Bourdain had quit in 2007, after the birth of his daughter. “I mean, I’ve had more time on this Earth than I probably deserve,” he confessed in an interview about the subject. “But now I feel that I owe this child who loves me to at least try to live a little longer, you know?” Seven months before his suicide, while on camera for Parts Unknown in the south of Italy, he spontaneously lit a cigarette after a satisfying meal. Bourdain offered the moment to his audience almost coyly, but after holding the first puff of smoke deep in his lungs, his eyes hidden behind sunglasses, for an instant I could have sworn Bourdain got emotional. Abruptly, the camera cut away to a child’s hands with interwoven fingers coming apart against the sky, followed by a slow zoom toward the upturned face of a wooden crucified Jesus statue. Given his explicit reason for quitting, the imagery hardly seemed subtle. Over the years, in interviews, his own writing, and on camera, Bourdain hadn’t been shy about referring to or joking about his own suicide—nineteen times, specifically by hanging, according to the July 8, 2018, article “Anthony Bourdain’s Long-Burning Suicidal Wick” by John E. Richters. I was 11 the first time suicide crossed my mind. Once you’ve visited the idea, I’m not sure you can ever remove the breadcrumbs leading back to its doorstep.

The shock of Bourdain’s death held an eerie symmetry: I was near the end of a Quixotic (the last of the giant windmills defending the horizon was only an hour behind me) 4,000-mile pilgrimage to the real location of the fictional Hotel de la Gloria, where, 45 years earlier in 1973, the filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni had staged the murder of a journalist, documentary filmmaker, and author named David Locke, gunned down in his room at the age of 37 in a case of mistaken identity. Compounding the central mystery of Antonioni’s metaphysical detective story and fatalistic fairy tale, The Passenger, Locke, the miscast hero of his own story, had secretly committed a form of suicide only a week earlier inside a different yet similarly lonely hotel room.

Played by Jack Nicholson, Locke at the beginning of the film is burned out, at the end of his rope, lost in the North African desert trying to report on a war he can’t find, unable to connect with anyone he meets. The closest he gets to understanding is decoding the universal gesture for do you have an extra cigarette?

“How far is it?” Locke asks his rebel guide as they climb up high into rocky hills.

“They will tell you when you get there,” his guide replies.

“Do they have arms?” Locke asks.

“Soon, when we get there.”

But we don’t get there.

And before we gain any more clues, almost immediately the guide abandons him when danger approaches in the form of a patrol crossing the desert on camels. On the way back to his hotel, Locke’s vehicle gets stranded in a dune. Amidst the silence, emptiness is everywhere around him, but it only reflects an even greater emptiness within. Locke is surrounded by a hopeless vacancy, pushed over some kind of existential edge. Whatever life force has taken him to this place has run out, and the many wars and conflicts he has observed have become faceless and interchangeable.

After abandoning the last assignment of his professional life, Locke bitterly takes the long journey back to his hotel on foot. In the room next to Locke’s, he discovers a man named David Robertson lying dead from a heart attack. They had shared a flight to the region, faintly noticed one another, then had a brief conversation over a drink the previous day shortly after they both arrived at the hotel. The stranger mentioned he had, “No family. No friends. Just a few commitments, including a bad heart,” adding that he shouldn’t be drinking, before coughing portentously and suggesting another. Locke had been testing his Uher recorder before this stranger entered the room and accidentally recorded the conversation.

“Beautiful, don’t you think?” Robertson asks Locke as they stare off at the desert.

“Beautiful…” Locke repeats, dully turning the idea over. “I don’t know.”

“So still,” Robertson says. “A kind of… waiting.”

“You seem unusually poetic for a businessman.”

“Do I?” Robertson turns away from the desert and smiles. “Doesn’t the desert have the same effect on you?”

“No,” Locke replies in a melancholy tone. “I prefer men to landscapes.”

“There are men who live in the desert.”

And Locke has failed to find them.

“I must’ve taken a wrong trail,” Locke confesses to Robertson.

We never find out exactly why Locke felt double-parked in his own life, beyond the interstices of the past refusing to be pruned from his present. But we know he assumed a dead man’s identity, a complete stranger beyond a single random conversation the day before, who Locke gradually discovers was the arms dealer for the war he couldn’t find. The corpse’s eyes are open and Locke leans over him and stares deeply into them. He touches the dead man’s hair gently. Two faces are positioned opposite each other, life and death glaring into each other’s mysteries. Has fate delivered him to the right place at the right time, or the wrong place at the wrong time?

The reading material lying on Robertson’s nightstand, with a skull on its cover, is a dangerously undeclared omen for Locke: South African author Eugene Marais’ The Soul of the Ape. In 1926, a Nobel Prize laureate named Maurice Maeterlinck scandalously translated and plagiarized much of Marais’ life work from The Life of White Ants (written in his native Afrikaans). Many attributed Marais’ eventual nervous breakdown and suicide to the trauma created by the theft of his ideas. What are the consequences for Locke attempting to plagiarize not just a book but an entire identity?

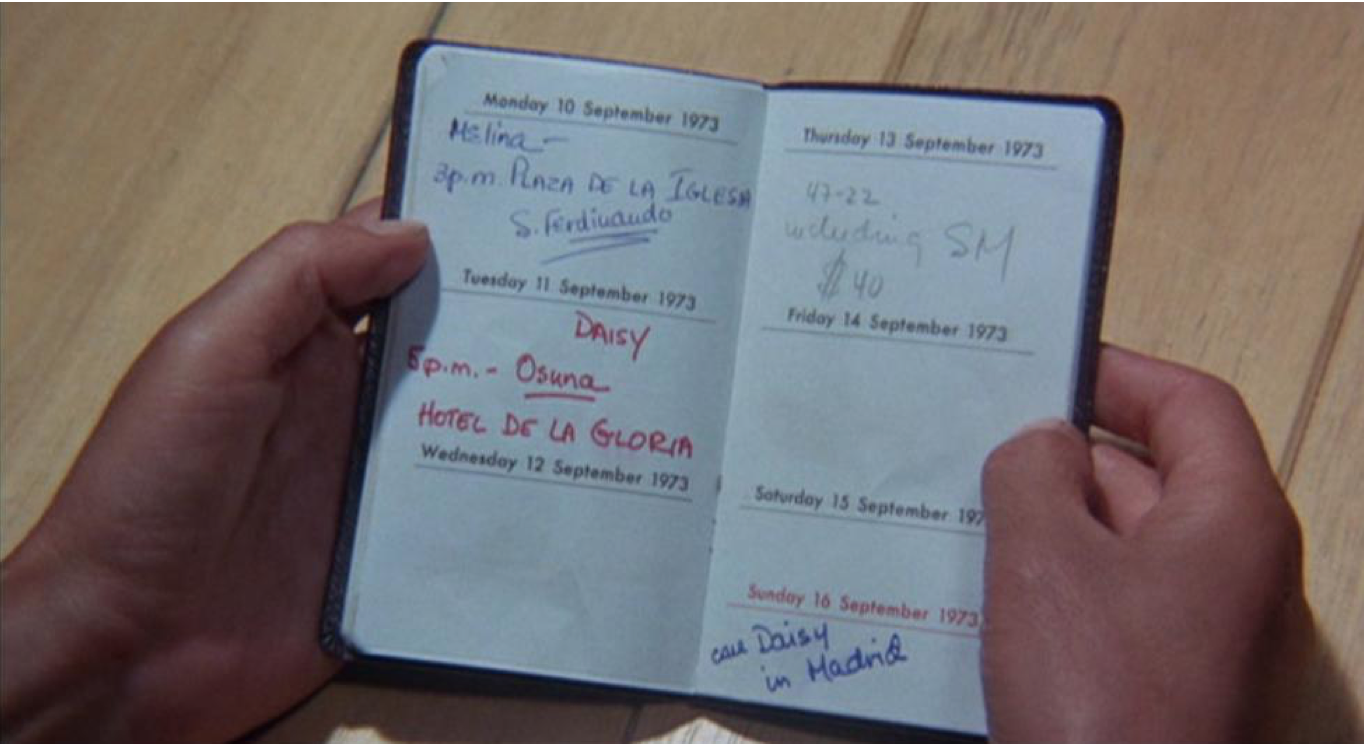

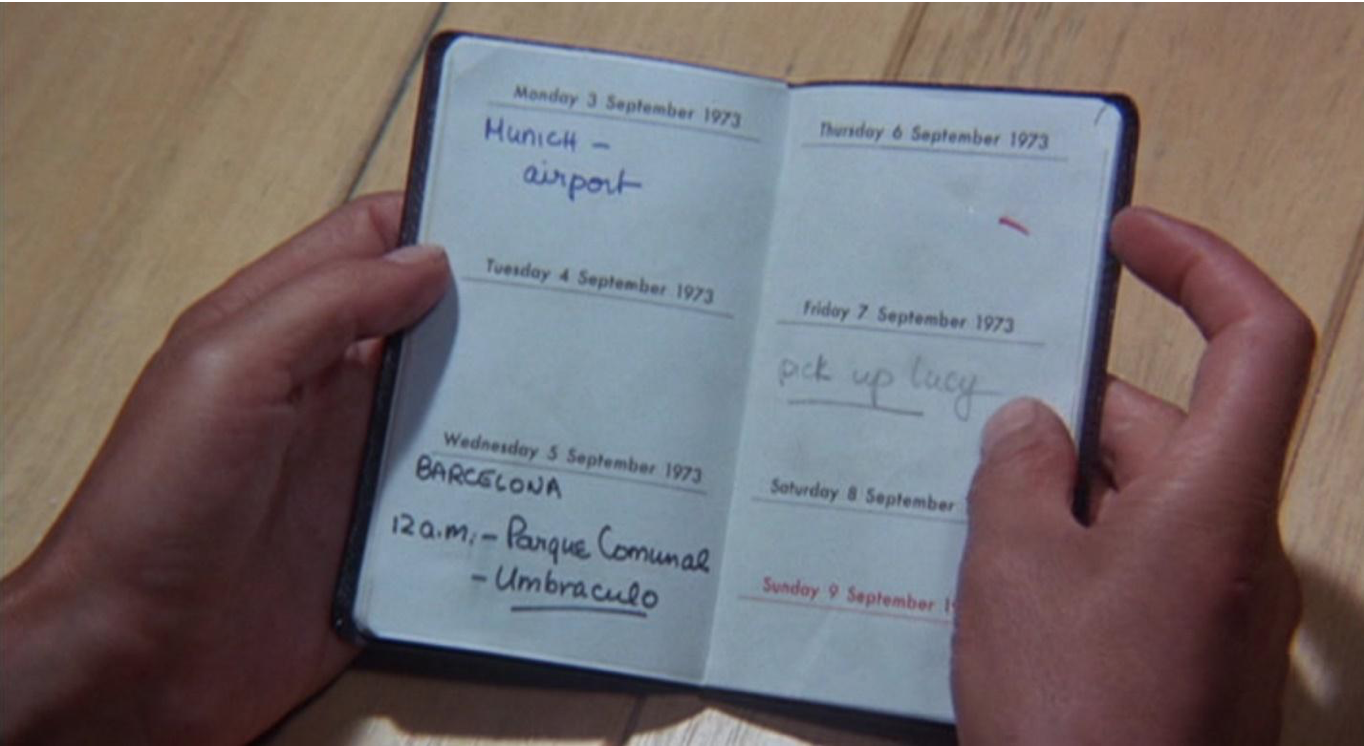

After Locke swaps passport photos, exchanges belongings (including a pistol he ominously discovers amongst the rest), and takes a set of keys from the dead man’s pocket, he carefully inspects Robertson’s appointment book.

Locke has no way of knowing it, but after turning the page from dates in Munich and Barcelona, he is studying the true date and location of his own death, via assassins seeking out his new identity of David Robertson, on Tuesday, September 11, 1973, at the Hotel de la Gloria in Osuna, Spain. And who is this mysterious “Daisy” in the appointment book that is supposed to be waiting for him there, and then waiting for a call from him in Madrid five days later? Who are Lucy and Melina, the other women mentioned? Are they women? Code names? Ciphers?

To find a life worth living, Locke has assumed the identity of a hunted life worth dying for. The gun residing in the dead man’s belongings is just the first clue. After its discovery, Locke casts a deeply accusatory glare in the direction of its former owner, lying next to an unfinished traveling chessboard in bed.

Locke drags the corpse to his own hotel room and trades clothes. He then reports the death of David Locke to the authorities. For motivation during this quietly profound scene of transformation of identity, Antonioni told Nicholson, “It’s interesting how little people act when there’s no one to act for.”

Locke’s only remaining guide into David Robertson’s life is recalling the conversation he shared with him the day before:

“Airport, taxi, hotel—” Robertson had lamented to Locke. “They’re all the same in the end.”

“I disagree,” Locke countered. “It’s we who remain the same. We translate every situation, every experience, into the same old codes. We condition ourselves… However hard you try, it stays so difficult to get away from your own habits.”

Yet Robertson’s death has presented Locke a chance to push his luck and try.

“Chance and chance alone,” Milan Kundera wrote, “has a message for us. Everything that occurs out of necessity, everything expected, repeated day in and day out is mute. Only chance can speak to us… Our day-to-day life is bombarded with fortuities or, to be more precise, with the accidental meetings of people and events we call coincidences.”

*

In fact, the Hotel de la Gloria never stood in Osuna, outside Seville; it was built and filmed in Vera, Spain, next to a bullring where I was headed. Antonioni had ordered its construction explicitly to facilitate the shooting of the penultimate scene: a more-than-six-minute unbroken shot that took 11 days to film—one of the most technically arduous and famously daring in the history of cinema. “I feel the need to express reality,” Antonioni remarked in an interview with Jean-Luc Godard, “but in terms which are not completely realistic.” Roland Barthes commented of this impulse, “You (Antonioni) show a true sense of meaning: you don’t impose but you don’t abolish it. This dialectic gives your films a great subtlety: your art consists in always leaving the road of meaning open as if undecided—out of scrupulousness.”

Antonioni intended the whole film to have the feeling of taking place over the course of a single day, suspended in time, “from early morning until some time before sunset.” Yet while this intention is not reflected in the date book’s inventory of several days’ worth of appointments, apart from the ending, The Passenger is filmed entirely in daylight, obscuring the timeline, lifting the narrative out of the expected path.

I lit another cigarette, turning over my own explicit reason for quitting, and wandered a few steps away from the gas station to watch a distant kettle of Griffon vultures floating over something in the desert like burnt paper suspended over a campfire. When I got back to the car, more confusion and sadness over the radio about Bourdain and the public grappling with yet another high-profile celebrity suicide. I’ve lost family, several close friends, and many heroes out in the culture to suicide, alcoholism, or overdoses over the years. While they warn you it’s dangerous meeting your heroes, most of mine have ended up suicides, and I’ve been left chasing after ghosts. Mike Tyson was the first person to point this out to me and teased, “Is suicide a prerequisite or something?” Which had never occurred to me until then and we both started laughing. We all gravitate to characters and stories we identify with; I’ve never been good at differentiating between living or dead or invented characters either. If the emotional stakes are there, how much does it really matter? I suddenly couldn’t help but see the similarities between Bourdain and the fictional protagonist of The Passenger I was chasing down in Spain. There was a spooky symmetry about the coordinates of their identities, both professionally and personally. I’d never made the connection before.

The character of David Locke had also been the story as much as the stories he covered. The world knew his name, sought his insights, and admired the bravery of his perspective and authenticity. Both Bourdain and Locke were intensely ambitious about the work they conducted around the world and achieved enormous levels of success. Yet a hidden undertow of personal dissatisfaction continually accompanied their professional triumphs. In life and death, their mythic tracks seemed to intersect.

“I’d like to be happy. I’d like to be happier,” Bourdain confessed to a psychotherapist in an episode of Parts Unknown that aired almost exactly two years before his suicide. “I should be happy. I have incredible luck. I’d like to be able to look out the window and say, ‘Yeah, life is good.’ I communicate for a living, but I’m terrible with communicating with people I care about… I feel like Quasimodo, the hunchback of Notre Dame. If he stayed in nice hotel suites with high thread-count sheets, that would be me. I feel like a freak, and I feel very isolated.”

In the same therapy session, Bourdain mentioned a nightmare that had haunted him “as long as I can remember.” He is trapped alone inside a vast, menacing Victorian hotel with endless rooms and hallways and no escape. Desperately searching for a way to get home, the tragic realization sinks in that he can no longer remember where home exists.

How Bourdain shaped his own legend with a self-described “lucky break” origin story of being fished from the slush pile at The New Yorker had always tantalized me, as it probably did thousands of other aspiring writers with enough rejection letters from far lesser places than The New Yorker to fill every inch of the walls rapidly closing in on us in cramped, falling down apartments. I can’t recall hearing even one other needle-in-a-haystack literary discovery story galvanizing anyone’s career. Impossible odds. Bourdain told us his mom had nagged him to give it a try. So had mine, hundreds of times. But after the first few dozen rejections, you’re already turning over whether the gamble ever had anything to do with “making it,” or if, like any serious gambling addict, masochism was always the secret payoff. Winning requires no self-awareness; losers can’t look away.

Bourdain described himself as a Chuck Wepner type, the human punching bag palooka who inspired Rocky. But Wepner’s dad hadn’t attended Yale or worked at Columbia Records; his mother never worked at The New York Times; Wepner never attended Vassar, and also didn’t end up writing 13 books, including two wildly successful memoirs in a voice that sounded not far from if Holden Caulfield had abandoned his dream of living in the woods and instead gone to culinary school.

Holden, like Bourdain, hid a lot of his private anguish in plain sight with humor. If Catcher In the Rye’s most famous word is Holden Caulfield’s use of “phony” (35 mentions), within the novel’s 240 pages Holden relies far more heavily on much darker concerns: “crazy” (77 times), “kill” (64 times), “depress” (50 times), “alone” (18 times), “suicide” (6 times), and of particular attention given the (mostly) atheist Caulfield professes to be, he mentions “God,” “Jesus,” and “hell” 623 times.

Bourdain acknowledged in his first bestseller, Kitchen Confidential, that his story might end his career as a cook and was unlikely to land him a television show or ski-trip invites from celebrities. Yet Bourdain hardly looked out of place sharing noodles with President Obama in Vietnam in 2016… on his own spectacularly beloved reality television show.

Like Bourdain, I endlessly devoured origin stories, especially of those personas notoriously forged in crisis—to take notes and dream, or at least sustain the delusion of having even a sliver of their worth to offer. I was never particularly concerned with their veracity; I was more enamored with the nerve and daring of their efforts at seduction and the careful curation of details—their attempts at crafting gateway drugs into the rest of their tellers’ lives in the hopes of turning the world into addicts. Few of Rembrandt’s most powerful portraits took anyone’s pose at face value; the Dutch master zeroed in on his subjects’ intention—he wanted you to see the emotional scaffolding. Reluctance, likewise, is itself a pose, often one of the most seductive, and any seducer worth his salt has to be a sucker for being seduced. Lying, after all, is a collaborative, cooperative act—every lie reveals the listener’s needs just as much as the liar’s, and the first victim of any world-class conman is always the same: himself.

It probably began for me with the secret double-life of Lewis Carroll, creating Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland while hiding in plain sight as Charles Dodgson, a shy, stammering math don at Christ Church Oxford. And at 16, before he ever acted a day in his life, Orson Welles lied through his teeth to the manager of the Gate Theatre in Dublin that he was a massive star on Broadway; nobody believed it, but his audacity charmed them and they gave him his first break. At 19, after World War I, Ernest Hemingway posed for history in a borrowed or stolen Italian soldier’s uniform. He hadn’t been a soldier; a mortar shell struck him while he was handing out cigarettes and chocolate. In A Moveable Feast, he lied copiously about the abject poverty he endured first starting out in Paris, while in fact living quite comfortably and traveling extensively for ski trips and bullfights on his wife Hadley’s trust fund. George Orwell attempted to hide the elite Eton education from his voice with a more common estuary accent in public and over the radio at the BBC. During World War II, Roald Dahl’s first published story, in August of 1942, was called “Shot Down Over Libya.” Nobody shot down his plane; he’d crashed after not locating the landing strip. On the Road, contrary to Kerouac’s claim of having written it in three weeks and of championing “spontaneous prose,” was heavily edited by the author before it saw publication years after the first draft was written. Jean-Michel Basquiat auditioned for the art world in the role of a kid who slept on benches in Washington Square Park, while he actually grew up with a father who was a successful accountant who drove a Mercedes, owned a four-story brownstone, and sent his son to private schools. O. Henry, the pen name of the short story writer of twist endings William Sydney Porter, gave just one interview during his lifetime and lied throughout; his daughter Margaret only found out about his literary career being launched from behind the walls of Ohio Penitentiary (hence his pen name, drawing from the first two letters of Ohio and last two from Penitentiary), where Porter was being held for embezzlement on a five-year sentence, after his death; in the depths of despair, he wrote in one letter from prison, “suicides are as common as picnics here.” The prison’s chief physician reported he had “never known a man who was so deeply humiliated” as Porter. Literature wasn’t even F. Scott Fitzgerald’s backup-plan to his life-long quest of escaping his shabby Midwest beginnings in Saint Paul for glory—that was intended to be in the trenches of World War I, after football came to nothing in high school because he was too small. From reading his letters, it was years into writing The Great Gatsby before Fitzgerald even realized just how much of his own life and shattered marriage he’d cannibalized to inform Jimmy Gatz’s transformation into Jay Gatsby.

“Dreamers lie,” Mercutio warned Romeo, shortly before his own death. And we know that when Shakespeare took to the stage to act in Romeo and Juliet, he hid behind Mercutio’s mask to deliver those words. Shakespeare also killed himself off before everyone else in the tragedy.

As much as Bourdain again and again reminded us he was the beneficiary of a series of “lucky breaks,” who really believed him? More importantly, did he? That’s what interested me most about Bourdain on a personal level: the fascinating way he created, projected, and stage-managed his own romantic role and intoxicating path from the self-described “vulnerable, goofy, awkward guy whose only success socially was to be the baddest guy in the room” to winning over the hearts of millions around the world. Orwell was the writer he most cited as a hero, who himself once ominously warned, “He wears a mask, and his face grows to fit it.”

According to a recent interview with David Remnick, counter to the myth, there was no slush pile submission. Remnick’s wife was friends with Bourdain’s mother and she passed the piece along directly. Remnick found the transaction adorable. “A mother’s ambition for her son,” Remnick recalled. “That was the beginning of Anthony Bourdain being published…I don’t know if there’s any way to put this other than to say he invented himself as a writer, as a public personality. It was all there.” Hook, line, and sinker, the world was addicted to Bourdain’s spirit.

At the age of 44, Bourdain’s transformation from a debt-ridden, uninsured, chef in recovery, who told us his first major dream in life had been to become a heroin addict, occurred after that New Yorker story launched him into the public’s consciousness. Along the way, the “hyper-violent, junkie” Byronic persona he’d crafted as a romantic’s survival strategy—a tapestry braiding Hunter S. Thompson, Jack Kerouac, and the aforementioned Orwell—seduced the world, but I’m not sure how long Bourdain stayed under its spell. Something always remained unrequited. Bourdain once confessed, “Anybody that writes a book or goes on TV with the notion that they have a story worth telling, that people might want to listen to, you’re really already, by definition, an aberrant personality and a monster of self-regard… That’s not normal. That’s often very much at odds with being a functioning, well-rounded, good person in the conventional sense. That kind of vanity, narcissism, self-regard, self-importance, and cheerful willingness to examine and share your feelings… if you’re sharing your feelings, it’s not sharing, it’s leaking.”

Bourdain was an obsessive cinephile, and I’d read that Antonioni—along with Truffaut, Kurosawa, Fellini, Godard, and Cassavetes—was one of his favorites. Maybe as a teenager he saw The Passenger with his parents, who he said made a point of going into Manhattan in the 1970s to see everything Antonioni did. I wondered, if he had seen it, whether the film’s themes rang any bells for him. For Antonioni, the themes he saw in the story reminded him of one of his—and my—favorite writers, Italo Calvino, who once defined a classic as something “that never finishes saying what it has to say.”

Calvino also wrote in Invisible Cities, my favorite novel: “Arriving at each new city, the traveler finds again a past of his that he did not know he had: the foreignness of what you no longer are or no longer possess lies in wait for you in foreign, unpossessed places.”

Sooner or later, after returning to any place you love, you run up against the intrusion of time’s sneaky crosswind. It blows against the ambient reassurance the returns will be inexhaustible, hold more impetus, richer details, and, if you’re fortunate, deeper meaning and resonance. The crosswind whispers that there’s no special guarantee that another return holds more of what you first found there. The fleetingness of your encounter is suspended. It’s a reminder each return is as fragile as the life that brought you back, along with all the life surrounding you—family, friends, acquaintances, strangers. Suddenly the complexion of everything streaking by out your window is imbued with the possibility that you might be glimpsing it for the last time. It was yours to always return to a minute ago, then it snaps into focus that you’re just passing through, spooked by the winking force of inevitability that somewhere down the line you’ll have to let it go.

Chapter Two

“For what it's worth, it's never too late to be whoever you want to be. I hope you live a life you're proud of and if you find that you're not, I hope you have the strength to start over.” — F. Scott Fitzgerald

I finally put the rental car back on the highway and absentmindedly stuck my hand out the window to surf the strange breeze, heading north toward the Tabernas Desert. Some signs advertised Oasys theme park, Spain’s “Mini Hollywood,” where Spaghetti Westerns like Sergio Leone’s For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly were shot, reimagining America’s Old West, often with traditional Japanese archetypes and storylines. The theme park had an abandoned gold mine, an Old West saloon, mock Western stores, and a zoo. The showcase entertainment featured mock bank raids and cowboy stunt shows. Or, on a daily basis, you could watch Jesse James, arguably America’s first modern celebrity, get shot in the back by America’s first celebrity stalker, Robert Ford. (James’ main rival for unleashing modern celebrity, Oscar Wilde, arrived in New York for his first American tour at the age of 27, only a few months before James’ assassination in 1882, with the press so eager to lay eyes on him they chartered a boat to intercept him at sea.)

If you stayed on the coastal highway for another 50 miles or so after leaving Almería, you’d collide with the Playa del Algarrobico and the salt water lagoon of Cabo de Gata, near San José, on which many scenes of 1962’s Lawrence of Arabia were shot. Fatal Exit, Mark Peploe’s story on which The Passenger’s script was based, may have owed something to Lawrence’s attempts to rewrite destiny in the desert. In many ways, the stories seem separated at birth (along with Hitchcock’s Vertigo). As a teenager, Peploe had hitchhiked around Europe and ended up at a bar in Almería where many members of the cast of Lawrence were also drinking. Lawrence, at 340 minutes, is a much longer character study than The Passenger, but at its heart asks the same question in manifold different ways of its protagonist searching for himself: Who are you? It finds its own artistry in going to remarkable efforts to avoid revealing the answer.

“When this war’s over, he can be anything he wants,” a general says of Lawrence in the film.

“Yes,” is the reply. “Well… at the moment he wants to be somebody else.”

I used to live near that salty lagoon where some of Lawrence was filmed which was pretending to be the Jordanian coastal city of Aqaba. Every autumn and spring thousands of migratory African birds flew across the Alboran sea to visit, the only location in Europe where they did. I had lived there with a woman in a small apartment in the dusty hills surrounding the town for several months during a year we shared in Spain in our mid-20s. We found that tiny town on the ocean by accident during a rainstorm when our bus broke down and I unwittingly entered one of the happiest sustained periods of my life. Not long after we arrived, the town was shut down, everyone watching Lance Armstrong on their televisions climb mountains during the Tour de France. Ten years later, with the most lucrative lie in the history of sports exposed, he would read something of mine and arrange a meeting in New York City to ask if I would be interested in ghostwriting his tell-all memoir. The government was suing him for well over $100 million. “They’ll never forgive Cancer Jesus,” he moaned. He took a sip of tea and told me that after reading my words he felt like we had some kind of shared outlook on the world. Based on my voice on the page, he was certain I could “get” him. “They loved me on the bike for the same reasons they hate me off the bike,” he laughed. The dangled percentage of the multimillion-dollar advance “Cancer Jesus” might share for ghostwriting his memoir represented, by far, the most profitable opportunity of my writing career, yet I found myself infinitely more preoccupied with the revelation that this tragic human being recognized a kindred spirit in me. And of course he’d meant it as a compliment.

A stray memory from San José: Late one evening, walking with my girlfriend in town, I was suddenly startled by my reflection in a storefront window across the street. Even though it only took a split-second to get untangled, I’d failed to recognize my unguarded self and it jarred me. My girlfriend caught me reflexively posing into some ersatz version of Brando and seeking a better angle to defend myself from being laid bare as I had been for an instant. She squeezed my hand. “You know you only do that pose for yourself, right? I’ve never seen you show it to anyone else. It’s never seduced anyone. And you’ll never know what worked with me or anyone else.”

This observation dropped a pill inside me that’s still fizzing. All these years later, whenever I’m blindsided by my reflection some place and momentarily unable to recognize who it belongs to, the same unsettling feeling returns, parsing noise from signal. Whatever thoughts or feelings I’ve been having up to that point become profoundly secondary to the fact that wherever I am, however I am, I’m inexplicably located in the reflection right then. A tourist to myself. You become aware just how consumed you are by everything else that’s not you the majority of the time you’re living your life.

“Life itself is a quotation,” Borges teased. “It only takes two facing mirrors to build a labyrinth.”

She’s happily married with a young son now. A couple years ago she sent everything she’d kept from our relationship—the detritus of four years together—to me in New York with a warm yet somber letter explaining how she’d just written up her will for the first time and if she happened to die suddenly, she didn’t want her family injured finding what she’d kept from our shared time. I think of this whenever I hear this exchange from The Passenger:

The Girl: People disappear every day.

David Locke: Every time they leave the room.

I remember vividly the afternoon she got up to leave on an otherwise unimportant day in an otherwise unimportant room and exited my life forever. I’d supplied the reason for her leaving: a secret correspondence with a girl I’d never met in person and never intended to meet, in a conversation where I was seeking another version of myself. I had secretly given up on the imploding version my girlfriend loved and believed in. She told me that my emotional betrayal in words and feelings with someone else was far worse than her one-night stand two years prior.

I didn’t argue. Nothing meaningful is worth keeping score over, yet everything we do counts.

Return anywhere after too long away and any place risks becoming a pawnshop of what you left behind and why. At some point in your life, you stop and look around to discover time is moving through you as much as you’re moving through time. Perhaps only more so in Spain, the country where, Lorca once proclaimed, “the dead are more alive than the dead of any other country in the world.”

For the remainder of the drive to Vera, another strange ghost from my past returned to haunt my thoughts. I spent the rest of the drive thinking about him.

He was an obscure writer whose suicide had been announced 11 years earlier, on February 7, 2007, at the age of 27. Sometimes there’s a strange intersection between those attaining their dreams and those living broken ones. Every iron in the fire doubles as a finger in a dike. This writer had written three books and many stories over nine years and, while getting close a couple times, never succeeded in having anything published until after his death, when a small, biannual, Vancouver-based art magazine put his words into print. In death, they granted his wish. It wasn’t any prestigious wall to hang his painting on. It didn’t merit any grand headlines anywhere. But longing is one of the only aspects of love I’ve had access to in my life and the feeling has a riptide that pulls me under.

The writer’s best friend had submitted a letter to the magazine that the writer had written while traveling abroad, a letter addressed to a movie actress on the East Coast who’d dumped him and he was hopelessly trying to win back. Or maybe he was really just saying goodbye. He’d originally seduced her by mail, but when they met it quickly fell apart. Perhaps he didn’t live up to her imagination. Or maybe he did, and that scared her off. Fantasy, Slavoj Žižek once remarked, is for those who can’t cope with reality, while reality is for those who can’t cope with their fantasies. Desire is reality’s wound.

I’d buried him in an unmarked grave somewhere in my mind after I left Vancouver for New York a year after his death and never looked back—until now. I’ve only seen Vancouver since as the backdrop in commercials, or television shows, or films—it’s one of the most filmed cities in the world, but it’s always pretending to be somewhere else, never itself, yet the unmistakable milky quality of light always gives it away.

David Locke: I mean, how do you get their confidence? Do you know?

David Robertson: Well, it’s like this, Mr. Locke… you work with words, images, fragile things. I come with merchandise, concrete things. They understand me straightaway.

In John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, the author offers the reader Vincent van Gogh’s Wheatfield With Crows twice, on back-to-back pages. The first time he includes this caption:

“This is a landscape of a cornfield with birds flying out of it. Look at it a moment. Then turn the page.”

And then again on the next page with a different caption beneath:

“This is the last picture that van Gogh painted before he killed himself.”

Berger proceeds to ask how the words have changed the image, and why inside us the image suddenly expresses and illustrates the words.

Why does this writhing landscape transform into a porous mindscape where the ambiguity of perspective and throbbing isolation are expanded by the uncertain direction of the crows and a path to nowhere? Is this painting an unflinching, silent scream of defiance against a world that never recognized his genius? Or is it something else entirely?

Beside the writer’s byline, before you read a word, the Vancouver art magazine cryptically included a caption which informed the reader the author had taken his life shortly after writing and mailing the letter. They didn’t say how or where or why. Just the fact, unadorned by context. But the irony of finally having his first words in print after years of desperation trying everything else made it nearly impossible to read the letter as anything but a suicide note. The letter changed the moment you knew exactly where the path led: a dead end. Every word functioned like bread crumbs to get you there. From the first words, you were left to forensically comb for clues—the letter his anonymous, fourth- or fifth-rate Wheatfield With Crows, I guess.

“What am I in the eyes of most people—” van Gogh asked his brother in a letter. “A nonentity, an eccentric, or an unpleasant person—somebody who has no position in society and will never have; in short, the lowest of the low. All right, then—even if that were absolutely true, then I should one day like to show by my work what such an eccentric, such a nobody, has in his heart… Though I am often in the depths of misery, there is a still calmness, pure harmony and music inside me.”

And maybe a clue as to why the world treasures the personal and artistic struggle of van Gogh more than any other artist is right there in the last three words. Oliver Wendell Holmes observed, “Most of us go to our graves with our music still inside us, unplayed.” Despite how far his mental illness and the unrecognized, tortured artist’s path exiled him from humanity into the suffocating isolation of his own private hell, somehow with the backstage pass of his letters he’s the easiest artist for us to empathize with.

Van Gogh didn’t start painting until he was 27 or 28. He had no formal training. Yet in only nine years he completed about two paintings a week, almost 900, before his death at 37. He famously was only able to sell one, Red Vineyard at Arles, which today resides at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. Van Gogh hated being photographed; only two shots of him exist, taken when he was 13 and 19 years of age, and their authenticity remains in dispute—they may be of his brother, Theo. But of his nearly 900 paintings, 36 self-portraits have survived, one less than for each year of his life. His likely last self-portrait, painted in September of 1889, soon after suffering a breakdown inside the Saint Remy asylum, van Gogh felt captured his “true character.” Mysterious how of all the portraits van Gogh carefully rendered, the character who invariably seems most estranged from his eye is himself.

If most of us tragically go to our graves with our music still inside us, what explains those enigmatic cases where only crossing the frontier from life to death seems to allow us to hear it? Van Gogh himself wrote his brother, “If I am worth something later, I am worth something now.” A self-inflicted act occasionally has the power to transform an artist into a martyr, but few suicides are public, and suicide notes left behind are the exception. The fine print of a human life gets stuffed away in an unsent letter taken to the grave.

Apart from marrying the woman who brought me to New York from Vancouver to be with her, I only have two vivid memories of 2009, the year I turned 30, before fleeing to start a new life 3,000 miles away in a place where I knew nobody. The first was the single strangest morning of my life, when I knocked on my Vancouver neighbor’s door to see if he wanted to go for breakfast, only to find him blanched by shock when he answered. He had just come back from the morgue, where he’d had to identify his brother’s body. He asked if I would help him collect the belongings from their mother’s condominium in a suburb of Vancouver, less than an hour’s drive away, where his brother had taken his own life only hours before. His brother didn’t live in the condominium; he’d made a pilgrimage there to die. I’d only met this brother once. He had the saddest eyes I’d ever looked into.

The dead brother’s beaten-up car was still parked out front when we arrived. My neighbor’s father was something of a war hero who liberated two sub-concentration camps in World War II and later went from a broke prospector up in the Yukon to fabulously wealthy after discovering a massive lead-zinc mine. Parks, and even a mineral, were named after him. But, in 1977, without warning, my neighbor’s father was shot point blank in the face with a .357 Magnum revolver by someone with whom he’d had a minor real estate transaction. Afterwards, according to the papers, the gunman walked over to the bar, put his revolver down, lit a cigarette, calmly told the barmaid, “There. He’s dead. He deserved it,” and with that, proceeded to pick up a drink he’d paid for earlier and nursed it until the police arrived. The killer pleaded insanity at the trial and died before serving his sentence for murder. The murder became part of Yukon folklore. My neighbor had never recovered from it, and the proceeds from his father’s will left him the rest of his life without the necessity of work to dwell on the loss. For a reason I was always too afraid to ask, the now-dead brother received none of the inheritance and had been living on welfare, often wandering around skid row. Once, he delivered a manuscript-sized love letter to a stripper he barely knew beyond receiving lap dances and got himself banned from her club for life. The gesture went over about as well as van Gogh offering his sliced-off ear to a girl in a brothel as an early Christmas present.

Before we got to the door, I asked who had discovered his brother’s body.

“The real estate agent who was showing the property,” he said, taking out his keys to unlock the front door.

I froze.

“Doubt we’ll get a sale from whoever she was showing it to,” he said under his breath, turning to look at me blankly as he pushed open the door. Gallows humor out of my neighbor’s mouth was a bit like hearing Mr. Rogers curse out a child.

I entered the residence behind him and quickly saw a length of rope the paramedics had cut lying on the kitchen table, its receipt from Home Depot from three days earlier beside it. Next to that, a puddle of whiskey at the bottom of a small bottle of Jameson. Two unopened packs of Nicorette gum. A lime-green BIC lighter on top of an empty pack of cigarettes, save one gnarled cigarette remaining. Some pocket change next to that. In the next room, beneath the remaining rope still hanging from the bannister upstairs, was an expensive vase belonging to their mother that my neighbor’s brother had used as an ashtray in the lead-up.

The second and last thing I remember before leaving Vancouver was attending the publication after-party for the art magazine that included the dead writer’s first words in print. Barring some kind of A Confederacy of Dunces ordeal (which only reached publication 11 years after John Kennedy Toole was found dead in his car in Biloxi, Mississippi, with a garden hose running from the exhaust pipe into his window), this would in all likelihood be the only occasion his words would ever be in print. Posterity is full of characters ignored while they were alive: Dickinson, Kafka, Poe, Plath, Thoreau—many loom in this pantheon. Maybe this is why the world’s neglect of van Gogh while he lived ties us to what he left behind with such emotional force: we inescapably identify with his tortured longing and desperation to redeem his own place and value. Van Gogh becomes a patron saint on behalf of our own lives of quiet desperation and by redeeming him we redeem the unseen, unmined treasures hidden inside ourselves.

How often does talent or even genius derive from a fragile or at least tempestuously fluctuating self-regard? Imposter syndrome, coined in 1978 as imposter phenomenon in an article published by Dr. Pauline R. Clance and Dr. Suzanne A. Imes, has nothing to do with devaluing achievement: its underlying compulsion is to measure. That’s where the bottomless well of neediness ensues. Because regardless of what we have or haven’t done, we all sell ourselves short. Ultimately, it’s just the question of assigning self-worth.

*

All my adult life I’ve made strange pilgrimages—I ended up writing a million words about them in one form or another before I was ever able to convince anyone to pay me for one. I was always clumsily articulating what I was seeking; maybe I was simply running away from my own life while clinging to an alibi. But I’ve always been fascinated with people who disappeared. At 18, I went looking for Bobby Fischer somewhere on the lam in Budapest. Right after Hurricane Katrina, I drove with an artist to film the locations where Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, and Martin Luther King, Jr. were murdered in New York, Jackson, and Memphis; along the way, we staked out a parking lot in Monroeville, Alabama, at seven in the morning until Harper Lee showed up to drop her 95-year-old sister off at her law office (where she continued to practice law until the age of 100). A waitress at a diner near Atticus Finch’s courthouse where Lee occasionally picked up cherry pie tipped me off: “Green sedan. Thick glasses. Not a shred of femininity when she gets out of the car to circle round and help her sister Alice with her walker. That’s your girl. That’s Nell.” By accident, my journalism career began a few years later on Easter Sunday in 2010, after I conned my way into Mike Tyson’s home in Henderson, Nevada. The former heavyweight champion offered these first words of greeting:

“How did this white motherfucker get inside my house?”

Boxing old-timers used to joke that Tyson had no style of fighting, he just fought everybody “like they stole something from him.” The story of his escape from being a vulnerable, serially bullied kid had given me a blueprint to do the same after a bullying incident at the age of 11 left me a near shut-in for three years. That was the first time suicide entered my awareness as a solution to an intractable problem—to my fragile thinking back then, couldn’t suicide be the biggest decision you could ever make and never regret? I wasn’t even a boxing fan, but Tyson’s story had sent me two places I’d never been before: a library and a boxing gym. Both saved my life, and for the first time offered a sense of purpose. It’s why I wasn’t afraid of Tyson hurting me when he approached in anger that first time. Tyson was a world-class victim long before he was a world-class victimizer. Genuine gratitude for anything he’d accomplished outside of a boxing ring wasn’t something he was all that accustomed to dealing with—a reaction, to be fair, he’d more than earned. But when he saw it in my eyes, I felt he might actually be more scared of me in that moment than I was of him.

Another time I pulled up to a mailbox next to a driveway on Lang Road in the backwoods of Cornish, New Hampshire, and about thirty seconds later a truck pulled up beside me with a very unwelcoming look on the face of the middle-aged driver.

“What are you doing there?” he asked.

“I’m just—” I paused to turn it over. Cornish didn’t have a gas station, let alone a motel. What the hell possible reason did anyone have to be in Cornish besides the obvious? “I’m just looking at that… mailbox.”

“Do you know who that mailbox belongs to?” he asked.

“I have a pretty good guess,” I smiled.

“Well then you should know he doesn’t appreciate it. And you should also know that your license plate and the make of your car have been taken down.”

“I have no intention of disturbing him and I’m on public property. I’ll be moving on in just a minute.”

“There are eyes on you,” he warned, before driving off into the woods.

So I took out my jackknife and pried one of Salinger’s plentiful “No Trespassing” signs off a tree as a memento of my favorite living “posthumous” author and went on my way. I circled back that night and saw his shadow behind a curtain in the living room window from his house up on the hill. He died four years later with 45 years’ worth of unpublished work lingering like an unsent letter. Curious that the story “A Perfect Day For Bananafish,” which would finally gain Salinger, at age 29, the literary fame and status he so craved, was predicated on the mystery of his protagonist Seymour Glass’s suicide, and how mysteriously Salinger wove a golden thread embroidering a glimpse of his last moments.

“They lead a very tragic life,” Seymour explained of this made-up, mythical species of fish. “... They swim into a hole where there’s a lot of bananas. They’re very ordinary-looking fish when they swim in. But once they get in, they behave like pigs… Naturally, after that they’re so fat they can’t get out of the hole again. Can’t fit through the door.”

What happens to them? Seymour is asked by a small child named Sybil.

“Well, I hate to tell you, Sybil. They die.”

Salinger would dedicate the rest of his literary career (and post-literary career, he declared in his last accidental interview) to throwing an ambiguous mix of Caravaggio-like chiaroscuro contrasts of intense light and shadows over the surviving fictional Glass family left picking up the pieces. He told his friend Lillian Ross, “I started writing and making up characters in the first place because nothing or not much away from the typewriter was reaching my heart at all… The trouble with all of us is that when we were young we never knew anybody who could or would tell us any of the penalties of making it in the world on the usual terms. I don’t mean just the pretty obvious penalties, I mean the ones that are just about unnoticeable and that do really lasting damage, the kind the world doesn’t even think of as damage.”

*

The scene at the publication after-party for the Vancouver art magazine was perfectly in keeping with the tragic misfits I’ve always been compulsively drawn to. The event was held downtown near skid row in a banquet hall inside an old hotel. Malcolm Lowry used to drink in the area in between efforts during the many years he spent writing Under the Volcano after arriving in Vancouver in 1938, a temporary move that ended up lasting 14 years before the outbreak of World War II. To my eternal delight, he intensely hated Vancouver, branding it a “genteel Siberia,” and lived off the allowance his father sent him from England, a sum more than he paid any of Lowry’s three brothers to slavishly work for him in England.

Lowry built a squatter’s shack which he fell in love with on the opposite shore across the inlet from Vancouver. At night, he’d look outside his window at his rickety pier and across the water and mists to where a Shell refinery had a huge sign with the “S” burned out, which shone through the darkness as “HELL.” According to Lowry’s wife, it represented all the civilization that lay behind it. In 1944, his shack burned down and Lowry was badly injured retrieving Under the Volcano’s manuscript. Three years later, in 1947, the book would be published and hailed by many as the most important novel since James Joyce’s Ulysses. A decade later, a coroner’s verdict declared Lowry’s death by choking on his own vomit “misadventure,” with rumors of suicide and foul play swirling ever after.

“No, my secrets are of the grave and must be kept,” Lowry wrote in Under the Volcano. “And this is how I sometimes think of myself, as a great explorer who has discovered some extraordinary land from which he can never return to give his knowledge to the world: but the name of this land is hell.”

And elsewhere in Lowry’s most famous work, a word of warning for someone who, like David Locke, might think about killing off their own identity: “How shall the murdered man convince his assassin he will not haunt him?”

I showed up at the party a little late, not knowing anybody, and moved around the room anonymously. Booze was flowing and the band they’d hired hadn’t taken the stage yet. Before long, I felt something akin to a low-rent Nick Carraway at the first party Gatsby invited him to in his mansion. Pushing through the crowd to find my way to the bar, everybody around me was gossiping about the letter the writer had written to the actress, eagerly sniffing around for clues and exchanging wild theories about who he was and what had gone so terribly wrong that he killed himself. Everybody was waiting for his best friend to arrive so they could interrogate him for some answers.

I was waiting around to have a word with him myself.

Chapter Three

Early on in The Passenger, David Locke secretly returns to his Victorian London apartment in disguise to retrieve some money for the unknown journey ahead following Robertson’s appointment book. Locke cases the living room before climbing the stairs to his bedroom. On the doorframe hangs a note:

“Where were you today? Tomorrow afternoon at Ossington Street? Love U, Stephen.”

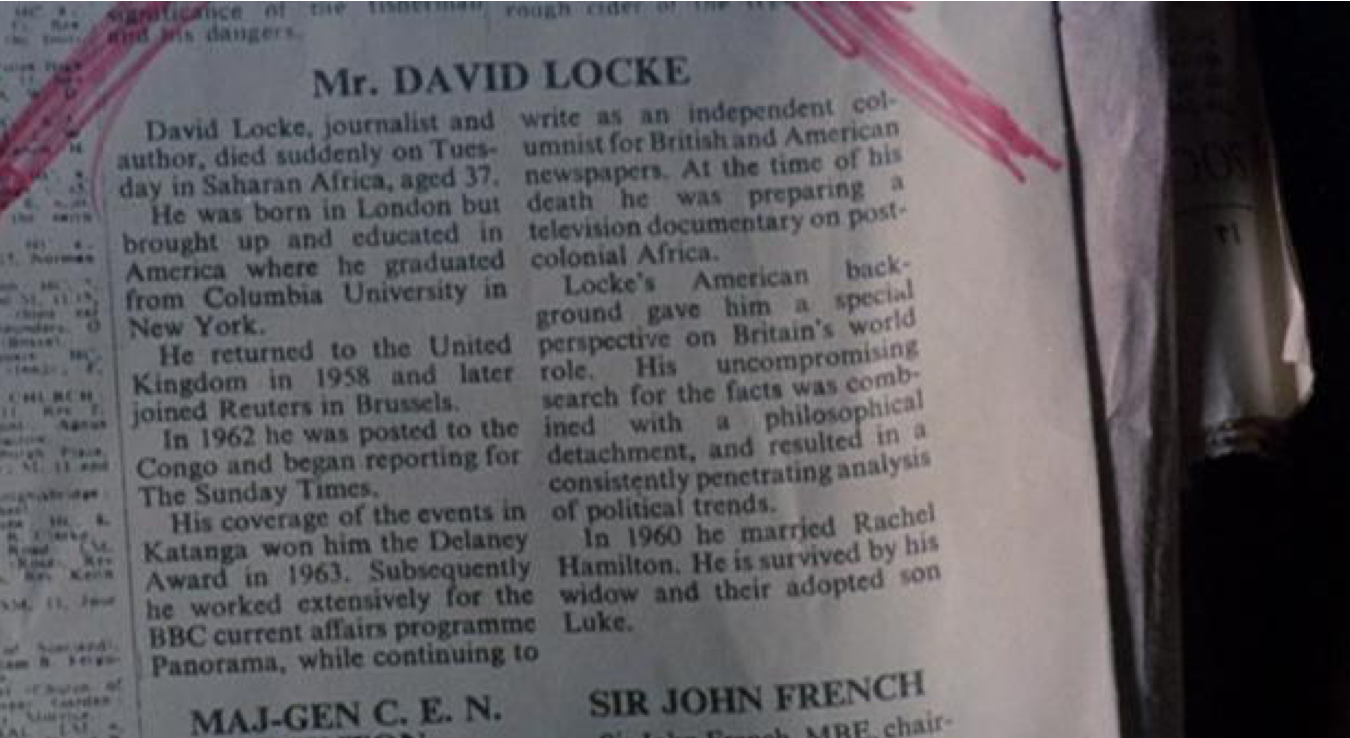

On his bed, Locke spies a newspaper with some red markings to it. He grabs the paper and discovers his own obituary, erroneously attributing his death to a heart attack inside a hotel room in Saharan Africa. (In 1954, after a terrible plane crash in Africa that everyone assumed was fatal, Hemingway also was able to read his obituary splashed across the front page of every newspaper on earth.)

The obituary informs us that Locke was/is married to a woman named Rachel and together had an adopted son.

We don’t know, however, if Locke was previously aware of the affair the note on the doorframe implies. When was he last home? The obituary informs us of the quality of “uncompromising search” barnacled with “philosophical detachment” that set his work apart while covering major conflicts in Africa (and in an earlier draft of the script, Vietnam). Maybe this applied to conflicts in his personal life, too?

In his office, we see on his desk Alberto Moravia’s Which Tribe Do You Belong To?, a book of travel writing about Africa. Paul Theroux reviewed it for The New York Times in 1974, beginning: “Travel-writing is one of the less harmful expressions of perverse restlessness, an interlude for the portable imagination.” For many years I’ve been an enormous fan and recent penpal of Theroux’s son, Louis, the BBC presenter of many acclaimed documentaries. I sent a note to Paul via Louis to see if The Passenger had resonated with him. He wrote back:

“What appealed to me in the film, which I saw in London on its release, was the sort of situation I have written about a number of times—a solitary man isolated in a foreign place, somewhat untethered, unconsciously influenced, bewitched by the strangeness of the setting and because of his isolation (no one is watching him) making a sudden risky decision that changes his life utterly. He is bored; very soon he is in action; then he is over his head…”

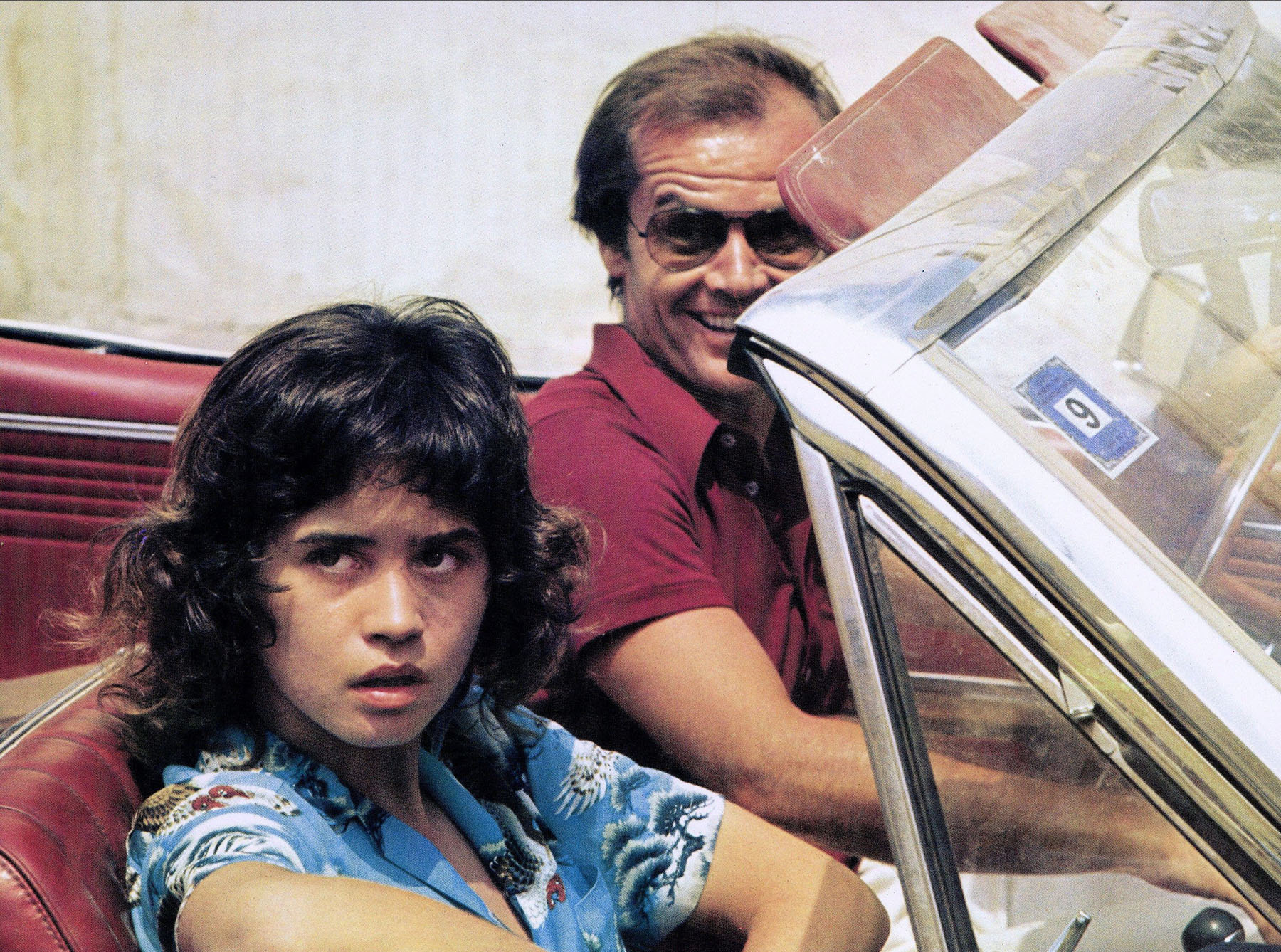

Nicholson’s mysterious female co-star and love interest in the film, Maria Schneider, is credited only as The Girl. We meet her for the first time, as does Locke, in London, innocuously inserted into the scenery of his abandoned life. Schneider arrived on the set immediately after her traumatic experience becoming, in a grotesque turn of events, a global sex symbol after starring in Last Tango in Paris opposite Marlon Brando. (“I felt a little raped,” Schneider said of being blindsided with the filming of its infamous “butter scene.”) An interesting thing Nicholson would tell me—which I’d never heard before—was that when Brando was indecisive about committing to Last Tango, director Bernardo Bertolucci approached Nicholson to replace him. In that film, Brando’s character—a middle-aged, tormented widower suffering in the immediate aftermath of his wife’s suicide—refuses to allow Schneider’s character to reveal her name or any element of her identity until the end of the film. Only then does Schneider softly comply, just as she fires a fatal bullet into Brando’s torso. As Brando collapses into the fetal position on the balcony, her last words are practising the speech she will recite to the authorities as her alibi:

“I don’t know who he is. He followed me in the street. He tried to rape me. He’s a lunatic. I don’t know what he’s called. I don’t know his name. I don’t know who he is. He tried to rape me. I don’t know. I don’t know him. I don’t know who he is. He’s a lunatic. I don’t know his name.”

And in The Passenger, deliciously, we never learn hers.

The Girl enters the film inserted into the scenery of Locke’s abandoned life in London, framed by the Brutalist architecture of Bloomsbury’s Brunswick Centre that Locke has wandered past. The two strangers notice each other only for a brief moment, yet each clearly registers the other for some reason. Was she waiting for Locke to pass? Had she been pursuing him? His new identity or the previous one? Or is this really just a chance meeting? Antonioni has supplied an abundance of incomplete information teasing the coordinates of the encounter.

Locke is on his way to a Munich airport to find a baggage locker box, number 58, which David Robertson had written down in his appointment book for September 3. The next appointment, two days later, is at Barcelona’s Umbracle at 12 a.m.

One of the supreme pleasures of The Passenger is not so much following the plot but trying to make sense of what the real plot or, for that matter, genre even is—thriller, mystery, ghost story, Quixotic quest, romance, drama, existential comedy, impressionistic documentary? It might be a sphinx without a secret, or perhaps a dance of endless veils. We get questions, incongruities, coincidences, strange patterns, misunderstandings, fragments of time, time collapsed, layers of shadows within shadows, and metaphors offered mostly in silence—many of which go unnoticed or unrecognized as significant by the characters. If you approach solving the film’s mysteries as a puzzle or riddle, you lose all the poetry.

“Chaos,” Henry Miller wrote, “is the score upon which reality is written.” It’s unsettling to consider just how regularly we fail to recognize the most important moments in our lives while we’re living them. Usually it’s only much later, when we’re helpless to do anything about it, that we gain any understanding. Yet sometimes we do recognize these moments as they arrive and intuit exactly the precise ways in which they will irrevocably define us to ourselves and shape the rest of our lives. Somewhere in any choice looms the risk of betraying to ourselves how hopelessly miscast we feel in the roles of our own lives while simply attempting to play ourselves. Jack Nicholson has faced his fair share of criticism for only playing himself in many roles; but it always struck me this might be the most supremely difficult role of all to inhabit for any actor. If art reflects life, where exactly was Nicholson expected to search to get pointers on how to do this?

“The actor is Camus’s ideal existential hero,” Nicholson once remarked in an interview. “Because if life is absurd, the man who lives more lives is in a better position than the guy who lives just one.”

He elaborated in another interview: “My films are all one long book to me, y’know, my secret craft—it’s all autobiography.”

And doubled down in another: “I think secrecy—and this is why I don’t do television interviews, for instance—is a very important tool to the actor, both in the dynamic of playing a part and in the way it’s perceived.”

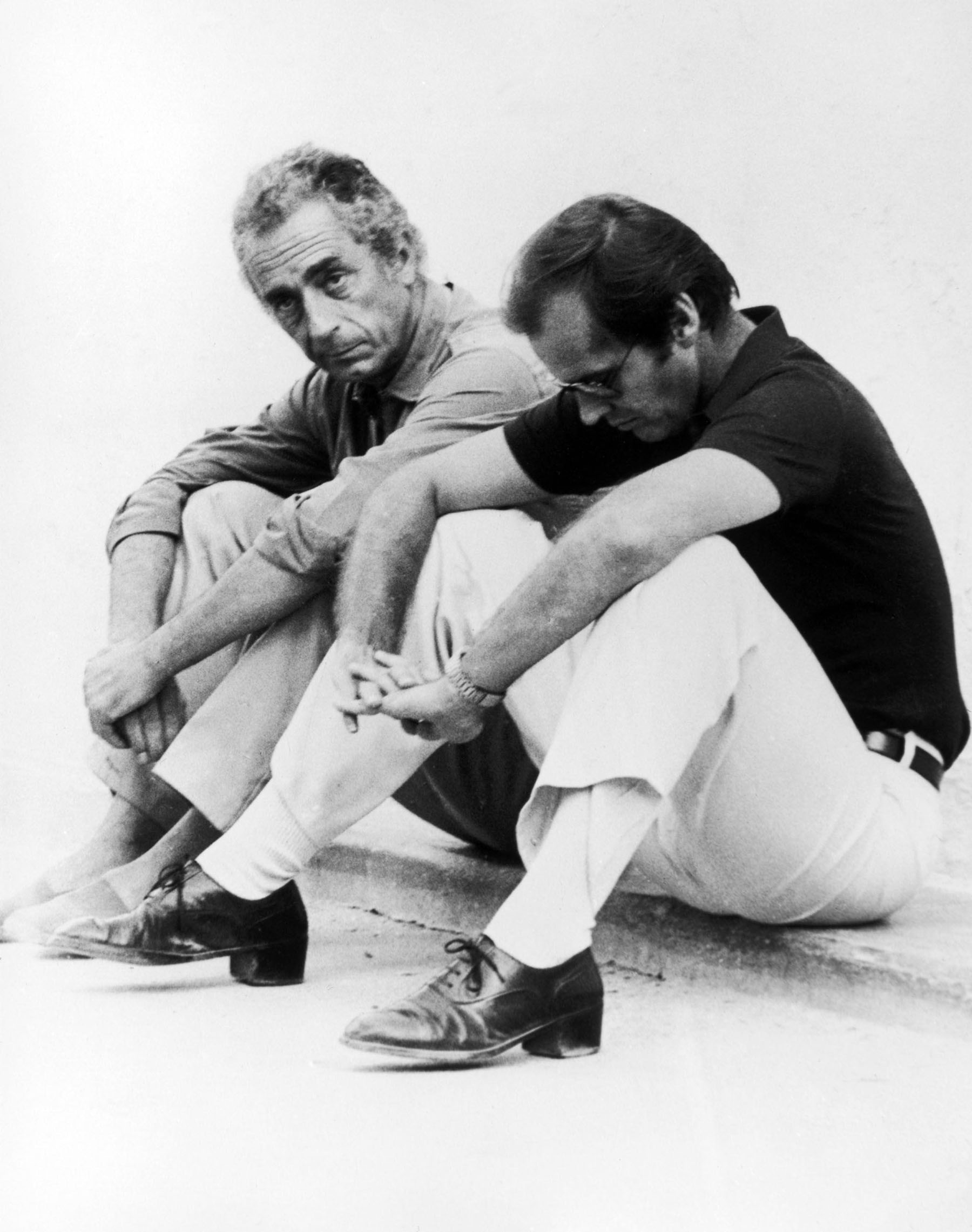

Nicholson left Neptune, New Jersey, and first arrived in Hollywood at the age of 17 in 1954. His first job was as an office worker for animators at Hanna-Barbera at the MGM cartoon studio. His dream was to follow in the footsteps of his idols and become the next James Dean or Marlon Brando. Early on he landed bit parts on stage and in soap operas, but it would take four years until his film debut in a trashy, low-budget teen film called The Cry Baby Killer. It took another 11 years of mostly forgettable Roger Corman parts to barely land his star turn in Easy Rider (people ahead of him backed out; Dennis Hopper didn’t want him for the role) in order to be deemed an “overnight success.” From there, entering the 1970s, everything took off in an extraordinary succession of films: Five Easy Pieces, Carnal Knowledge, The Last Detail, Chinatown, and, after The Passenger, his first Oscar for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. He closed his Oscar speech by thanking his agent, “who about 10 years ago advised me that I had no business being an actor.” By the time Easy Rider had rolled around to find him, he’d mostly given up on the profession. Suddenly he found himself being discussed as his generation’s answer to Humphrey Bogart.

In 1974, the same year Nicholson worked on The Passenger, two researchers from Time magazine digging into the 37-year-old actor’s life made a startling discovery about his past. The researchers got in contact with Nicholson and alerted him to the fact that the woman he knew as his sister was in fact his mother, and the woman he knew to be his mother was actually his grandmother. There were two likely candidates for his biological father; they had both taken their secrets to the grave some years earlier.

The first was Eddie King, a bandleader who hosted a weekly radio show straight out of Salinger’s fictional Glass family origin story, focused on child prodigies: Eddie King and His Radio Kiddies. June was King’s main companion on stage, accompanying him with dance numbers, doing impersonations, or singing while King played piano. He managed her career while she sought her big break in New York. In 1936, during the summer before Nicholson was born, June met Don Furcillo-Rose, a Vaudevillian performer and showman, on the Jersey Shore. He was much older and already married. The latter detail, June was unaware of. But soon enough, while on the road with a dance troupe, June discovered she was pregnant. Early in 1937, June disappeared from her home in Neptune, New Jersey, and would give birth to John Joseph Nicholson on April 22, 1937. He was born a bastard, a secret kept by the three women closest to him until the researchers’ phone call 37 years later. (That Nicholson would begin production on Chinatown immediately after learning of these elements of his own family history certainly adds a layer of intrigue to how he confronted the famously sordid denouement of that film.)

Nicholson was reportedly “shaken” by the news and refused to ever meet either of the men most believed to be his biological father.

“What is he searching for? Perhaps he searches for his destiny. Perhaps his destiny is to search.” — Octavio Paz

*

Jack Nicholson has always meant more to me than any other actor in film. I saw The Shining for the first time at the age of five and spent a lot of time checking into the Overlook Hotel as a fly on the wall growing up. At 17 I lost my virginity to a girl in my father’s attic with the film playing on a VCR on a cheap television nearby, soundtracked by Krzysztof Penderecki’s chilling score. My father had taped a censored television version from around 1984 or 1985 onto a shitty, beaten-up cassette. We had it for years before the ribbon snapped from frequent use. Setting aside the plot and its obedience to the horror genre, many aspects of the mood and atmosphere of the film felt like a family home movie for me. We didn’t have any home movies of our own. I didn’t know what genre my life would be at any given moment and it rarely felt in my control.

My father and I were about the same ages as Jack and Danny Torrance the first time I saw the film. The way Danny’s anxiety seemed to psychically connect the Grady twins’ plea to “come and play with us… forever, and ever, and ever” with his mother’s palpable desire for him to never grow up and remain her playmate had a lot of overlap to my own relationship with my mother. My mom never had a childhood growing up during the Hungarian Revolution in Budapest, and at times I felt torn that mine was being used as a kind of Potemkin childhood to help repair her own. I was slow to recognize my father’s increasing dependence on alcohol, but looking back I don’t think it took long before I was subconsciously processing it as a form of protracted suicide. There was never a binge or a hangover, but the consumption was methodically steady and never acknowledged. Being ensnared in the large and small hooks of denial is at the core of the Overlook Hotel’s menace and horror. Like Danny’s parents, my parents’ marriage was in slow-motion free fall. What was cleaving them apart was beyond my understanding, but was nonetheless being closely observed, internalized, compartmentalized as normal. I felt the force of an organic tension crushing my family without any clue where it came from or how to stop it.

Physically, Nicholson as Jack Torrance was a dead ringer for my father: the exaggerated eyebrows, the feral yet penetrating gaze, receding hair, the volatile temper and unsettling charm, the almost obscene casual intensity of his presence. They seemed so deliberate. Both meant to shock, whether for a laugh or to instill fear, but in other moments, their 1,000-yard stare made you feel a million miles away from them, betraying the unsettling sense you didn’t know anything about who they really were and never would. I adored and feared them both.

Ever since my father explained what “overlook” meant back then, it remains my favorite word in the English language. The lovely double-meaning and radical ambiguity of either a clean view or the denial of what’s right in front of you. In isolation, my mother meditated for two hours each morning; in isolation, my father drank on our back porch for two hours each night after he came back home from the office. In isolation, my mother read many classics of literature; in isolation, my father struggled to write one. There were a lot of arguments the rest of the time, but never about the elusive, unnamed atmosphere that was breaking my heart. My father was burned out on practising child protection law in a way that felt similar to Jack Torrance’s relationship with being a school teacher. It wasn’t who he wanted to be, but there were many legitimate reasons to try. Like Torrance, my father wanted to write novels. Unlike Torrance, my father had the talent to meaningfully occupy that role. He’d had a play produced at 18 and made radio documentaries for the CBC at 20, recording on the same Uher model Locke used in the desert. The first noises I remember hearing are him fiercely attacking a typewriter before dawn. The sound delighted me. There was always hope his perseverance might pay off, that eventually he might find his way to break through to who he most wanted to be. But he never could. Over the years, the many starts never led anywhere but another frustrated beginning. And then another. And another. That Sisyphean abiding frustration did the lion’s share of work defining the face he wore in my childhood in dark, brooding moods.

After The Shining, my father and I devoured everything of Nicholson’s work in film that we could get our hands on. Nobody took movies more seriously or was more fun to watch them with than my dad. And Nicholson’s magic, especially during the 1970s, was one of the most special things we shared. My obsession with The Passenger, once I found it, felt in hindsight like a foregone conclusion. It was the only film of Nicholson’s my dad could never find while I was growing up.

So it was especially surreal, a few years ago, when Jack Nicholson’s private number fell into my lap.

I was at lunch in Manhattan with someone who worked at a major magazine. We've been friends since I moved to New York City. He was remembering one of his first jobs working in the film industry, as a director’s assistant twenty years earlier. He laughingly recalled being put in charge of their rolodex which listed all the phone numbers of actors they were looking into casting for a now cult-classic film. After throwing out some of the names, he smiled recalling the number next to the name “Uncle Jack.”

“Not Nicholson?” I interrupted.

“I assumed so,” he said in his nasal accent.

“Please god tell me you made a copy,” I pleaded.

“Please,” he scoffed. “Of course I did. But it was 20 goddamned years ago. It’s lost. I have no clue where it is. My wife may have even thrown it out at some point.”

“Could you do me the biggest favor in the world and look for it one of these days?” I begged.

He sighed. “I’m real busy. But I’ll dig around in a couple weeks. Even if I do have it, who knows if it would still work?”

A month later I got a phone call. He’d searched and miraculously found it. The names and numbers were barely legible, but Uncle Jack’s was there.

“Don’t tell anybody where you got it, but lemme know how it goes,” he laughed.

A couple weeks after that I worked up the nerve to dial the number. A woman answered the phone:

“Nicholson’s…”

I tried a dozen different ploys to find a way in to talk with him and each was summarily shot down. Just before it was clear there was nothing left to try and she was almost feeling sorry for me, the last thing I told her was confessing the thing I’d most want to talk to him about was The Passenger.

“Oh he loves that film,” she said, her tone entirely different than before. “He’s not talking to anybody these days, but that might work. It won’t work. This isn’t going to happen. But I’ll tell you what. I’ll run it by him. It would take a miracle for him to talk with you about it. But who knows? I promise I’ll run it by him. Who would this be for?”

“Me,” I said.

“Oh,” she laughed in surprise, and hung up the phone.

I wanted to ask him why playing David Locke—of all the indelible characters he’d played in over half a century working in film—the bizarre, hermetically sealed protagonist in Antonioni’s hermetically sealed masterpiece The Passenger, was the greatest adventure of his career.

I never heard back.

Six months later, I was invited to use the number again through a mutual friend in show business (who didn’t know I already had the phone number), whose daughter curates Nicholson’s extensive private art collection. This friend agreed to put in a good word for me. Somehow, to everyone’s astonishment, it worked. And, despite rumors surrounding his retirement from acting due to suffering from dementia, Alzheimer’s, or just the garden variety memory loss from being 81 (false, it turns out), Nicholson was remarkably lucid and articulate speaking over the dull rattle of wind chimes from outside his Mulholland Drive residence for the half hour I spoke with him.

After David Locke conducts the final interview of his career and life with a witch doctor in the desert, Nicholson teases in the commentary he recorded for The Passenger: “Maybe the real subject of every interview is how you can’t learn much about someone from an interview.”

In 1982, Nicholson acquired the rights to the film from MGM and added it to his extensive private art collection worth well over nine figures that included Dali, Picasso, Magritte, Modigliani, Rodin, Matisse, Bouguereau, and Botero. The film wasn’t easy to find in theaters until millions were paid to restore it in 2005 and it was re-released.

Over the course of a career that won three Academy Awards and amassed more nominations than any male actor in history, the role Nicholson most regretted turning down was not Michael Corleone or starring opposite Paul Newman in The Sting—it was Jay Gatsby. “The only really good role I’ve rejected—” Nicholson explained, “and I could kill myself—was The Great Gatsby. Since I was 18, people said I should do Jay Gatsby. I didn’t really go after the part for, well, personal reasons I don’t want printed.”

He turned the Gatsby role down to play David Locke, fatally chasing down his own version of “Daisy.”

In 1985, Antonioni himself confessed that from all his films, “I think that the character who is closest to me is the journalist (Locke) in The Passenger.”

*

From a recording of Locke’s last interview with a guerilla leader fighting in Chad, in which Locke is interrupted with this reminder about the limitations of his professional reputation as an “objective” journalist:

“Mr. Locke, there are perfectly satisfactory answers to all your questions… But I don’t think you understand how little you would learn from them. Your questions are much more revealing about yourself than my answers would be about me.”

At the Munich airport, Locke opens box 58 to discover a small black bag stuffed with Xeroxes inventorying an extensive array of weapons Robertson was seeking to sell the guerillas to overthrow the government in North Africa, weapons to be sold for the war Locke was unable to find and passively cover as a journalist.

While he’s processing this information, Locke has attracted attention. Two men nearby notice him and follow his movements closely.

At the airport car rental counter, the woman working behind the desk asks him how long he wants a car for.

“For the rest of my life,” Locke answers cheerfully.

During his drive out of Germany, Locke turns a corner and is caught behind a horse-drawn carriage. His pace is slowed. For a brief moment, we catch a glimpse of a young woman who looks remarkably like The Girl from England—same length of hair, wearing the same colors—walking on the sidewalk next to the carriage. If this is indeed the same woman, this is Locke’s second limited encounter with her. Antonioni has her jade blouse cast against a lime green wall, more shades of green all around her from hedges, trees, and grass. Locke himself is wearing a forest green shirt under his jacket.

Locke passes by the girl and parks his car next to a church and wanders through its cemetery. He enters the church, where a wedding is underway, and anonymously watches from the back.

Time collapses: a jump-cut to a memory of his own failed marriage back in England. It is some autumn from the past and Locke is laughing maniacally as he stokes a bonfire in his backyard, neighbors looking on in horror while his wife rushes out in a nightie to berate his actions. “Are you crazy?” she screams.

Antonioni has played a trick on us, though: this is not Locke’s memory, but his wife’s. His wife-turned-widow, in a different season now, is staring out the window of the home they once shared looking out over the backyard where the fire once blazed.

Back in the church abruptly, the wedding congregation has left, and the two men from the airport approach Locke suddenly and ask him for the papers he retrieved from box 58. Locke suppresses a wry smile as they leaf through the weapons schematics. Satisfied, they hand Locke an envelope filled with money and remind him that agents from the “present government” will be pursuing him to “try to interfere with you.”

Locke’s first stop in Barcelona before his scheduled meeting is to wander over to the Transbordador Aeri del Port, built in 1929, and ride a cable car over the city’s harbor. The old conductor asks Locke if he agrees the view is beautiful, but Locke isn’t listening. He’s elated at the prospect of something unspoken and mischievously asks the conductor’s permission to fly. The conductor laughs and nods approval. Locke spreads his arms out over the ocean and for the first time since we’ve seen him, maybe the first time in his life, he silently rejoices in private liberation, soaring above the water.

Locke is next seen waiting alone on a cast-iron bench for Robertson’s next appointment, inside the arrestingly beautiful 131-year-old Umbracle (House of shadows) in Ciutadella Park, surrounded by tropical and subtropical plants originating in 20 countries from four continents which prefer shadows. Children are playing near him—chasing one another—but he’s lost in private ruminations. They say you can’t eavesdrop on a man in prayer. An old man approaches feebly with the use of a cane.

“My name is Robertson,” Locke notifies him half-heartedly, perhaps facetiously.

The old man, hard of hearing, leans over.

“I’ve been waiting for someone who hasn’t arrived,” Locke laments.

The old man laughs and turns back to the children playing. He points his cane at them, “Niños, I’ve seen so many of them grow up. Other people look at the children and they all imagine a new world. But me? When I watch them, I just see the same old tragedy begin all over again. They can’t get away from us. It’s boring.”

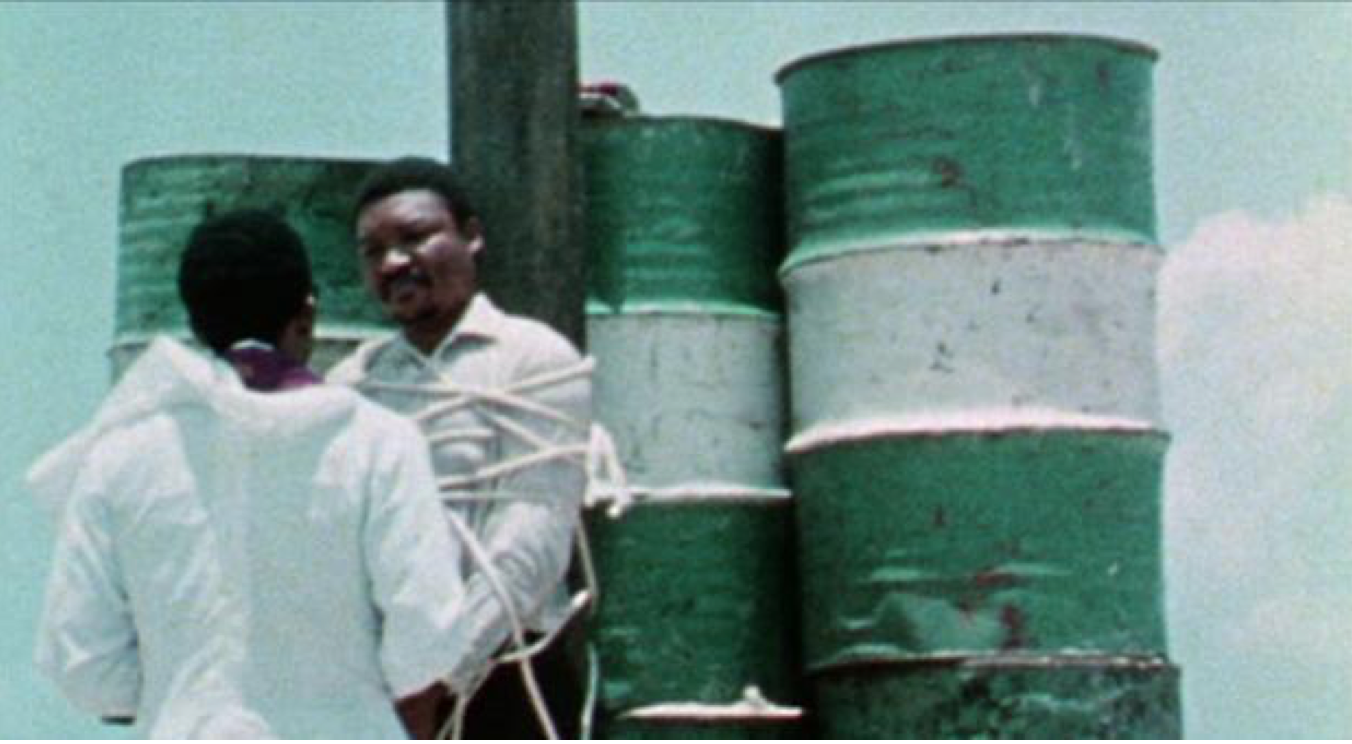

Back in London, meanwhile, Locke’s widow Rachel is searching through the detritus of her husband’s life. Death has renewed her interest in it. A producer who worked with Locke is showing her grainy documentary footage of an execution by firing squad Locke has secretly filmed with Lake Chad in the background. We hear only the waves lapping the shore. Here Antonioni controversially presents us with actual documentary footage of an execution for this scene that he never divulged publicly how he obtained. A curious crowd gathers to watch a Chadian man tied up to a wooden post on a platform with green and white striped oil drums stacked up behind him. A priest dressed in white offers him last rites. Soon three uniformed soldiers march into position on the beach and take aim. All fire. We watch the effects from a distance. There is no gore. Not even any blood visible from the entry wounds of the man’s white dress shirt. All we see is the bound man’s head slowly bow just before another series of shots are fired and his body slumps forward as his weight removes the slack from the tangle of ropes binding him. As the camera zooms in on his face, the footage grows blurry, but even in the low-resolution we can see his large eyes lifelessly open until a final shot finishes the gruesomely transactional task. Our perspective is Locke’s passive perspective of this event. A key hole to objective reality. His widow is now peering through it.

Upset, she gets up to leave the producer’s office, but not before asking him if he can find a man named Robertson she has heard was staying at the same hotel as Locke in North Africa. She wishes to talk to him.

Rachel Locke returns to her lover’s apartment in a daze.

“So,” the lover intrudes. “Why don’t you try to forget all about it?”

“I know it’s stupid,” she confesses softly, staring out the window. “I didn’t care at all before. Now that he’s dead, in some strange way, I do. Perhaps I was wrong about him.”

“If you try hard enough,” her lover responds. “Perhaps you can reinvent him.”

Rachel lunges in anger at his face with her nails, but when he tries to console her, she breaks free and calls her husband’s producer. The Avis company from the Munich airport has informed him Robertson is staying at the Hotel Oriente in Barcelona, he tells her. The producer is headed there now. She will follow.

The Hotel Oriente is located on Barcelona’s Las Ramblas, created in 1440, which Lorca once described as “the only street in the world which I wish would never end.” I remember finding it for the first time at 18. I got lost after discovering Joan Miro’s famous mosaic, a cosmos of 6000 irregularly-placed, unprotected, multi-colored tiles, trampled by nearly 78 million people strolling the Ramblas every year. I wandered under the tree-lined boulevard and Antoni Gaudi-sculpted lamps and heard before I could see the most beautiful fountains in the city. I bumped into the opera house and then La Monumental bullring. At some point I ran into the world-famous flower and caged bird markets.

We find Locke near his hotel walking directly past his former producer and dozens of bird cages on Las Ramblas to cross the street and have his shoes shined. The room Locke enters is full of mirrors and calendars. Before the shoe shiner can begin, Locke notices his producer outside from the mirror’s reflection and abruptly flees the shop before his old life collides with his new one. Running down a side street, Locke ducks off into a nearby building, which turns out to be the 19th-century gothic Palau Güell museum, designed by Gaudi. He pays admission and races up the stairs to take refuge in the fantastically nightmarish shapes and shadows looming above on higher floors, colored by the light that seeps in through stained glass. Tourists are wandering around the museum listening to taped guided tours from plastic speakers they hold up to their ears.

Locke enters a new room and—third time’s the charm—stops to look at The Girl sitting on a bench reading a book. A security guard is dozing under a birdcage down the bench from her. She turns to look at Locke and he begins his approach.

“Excuse me,” Locke begins. “I was trying to remember something.”

“Is it important?” she replies.

“No,” Locke says, and glances around the premises. “What is it, do you know? I came in by accident.”

“The man who built it was hit by a bus,” The Girl explains, by way of symmetry.

“Who was he?”