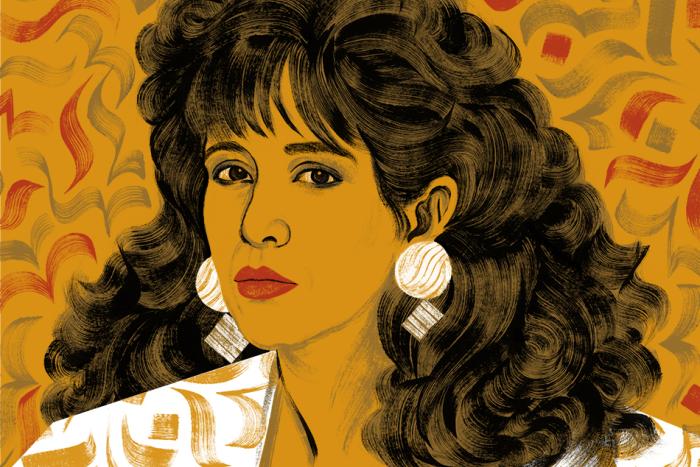

Darcy Losada was trying to save up enough money to pay for her undergraduate degree in Design and Communication. Her favorite flower was the black rose, and she hoped, one day, to publish an anthology of poems she had been working on.

A young man called Omar Alejandro Dueñas Zamora began stopping by the ice cream shop where she worked to flirt with her. He would flatter the color of her eyes whenever he bought an ice cream. Eventually the two began dating.

One evening when it was Darcy’s turn to close the shop, thirteen thousand pesos went missing from the cash register. Being the only other person present at the time, Omar was a suspect. The shop owner delivered Darcy an ultimatum: she had to break up with her boyfriend and compensate him for the loss, or he would report both of them to the authorities. Darcy consented. Omar began sending her threatening, descriptive messages about how he intended to kill her.

On March 24, 2013, Darcy’s mother, María Isobel, received a call from her daughter’s phone at 9:15 p.m. Amidst a cacophony of shouts, punches, and blows, María Isobel could hear Darcy sobbing. Then the line went dead.

María Isobel had a gut feeling that the worst had happened. She left the house and begged the authorities for help, but was not taken seriously. Her first stop was Mexico City’s investigation unit that specialized in kidnappings, but they dismissed her peremptorily since no ransom demand for Darcy had been received. After being asked to go to another department of the attorney general’s office, which also couldn’t assist her, María Isobel finally managed to get a missing person’s report filed at the Centro de Apoyo de Personales Extraviadas y Ausentes (Support Center for Missing and Absent Persons). They were reluctant to do so immediately, suggesting that she should wait a day in case Darcy showed up.

At 7 a.m. the next day a female body was found in the San Simón Ticumac area. The victim showed signs of asphyxiation and was covered in bruises. Later on, María Isobel would tell the press that, when the police called to notify her that a body had been recovered but it was unlikely to be her daughter because it was a “woman aged between 30 and 40 years old,” she felt a small breeze in her hair. “Darcy always used to ruffle my fringe,” she said. “Mothers have a special intuition. I knew it was her.” She was right.

Phone records confirmed that Omar had been in San Simón Ticumac at the time of Darcy’s murder. These were backed by video surveillance footage that showed him coercing her into a van, where she had presumably been murdered before being tossed back onto the street. At Darcy’s burial, someone left a black rose on top of her grave. She would never get to fulfill her dream of going to university.

The Mexican journalist Oscar Balderas, who is known for his investigative reportage of femicide and sex trafficking, had been invited to Darcy’s funeral, where he was able to speak to family members about her life and get a better sense of who she was beyond what had been written in the police files. Her family and friends were well aware that Omar had been abusive in the months leading up to Darcy’s death. She had said repeatedly that she feared for her life, even tearfully imploring her mother to look after her cat, Sally, in case she was killed. Nobody went to the police despite the high risk of a femicide because of a complete lack of trust in the system of law enforcement. They were terrified that Omar would almost certainly kill Darcy in retaliation if he found out that the police had been notified. Balderas recalls one of Darcy’s uncles lamenting the fact that, “If we had trusted the authorities this crime would not have happened, but in Mexico, when you file a complaint, it’s like buying endless trouble with your aggressor.”

***

Purple is the color of dissent in Mexico City. It comes to the city at the beginning of spring, when the jacaranda trees begin to flower. They appear overnight, dotting the lush canopies that hang over the historic center. The blossoms intermittently dot the green paths of Alameda Central, the first public park in the history of Latin America. The closer you get to Zócalo, the main plaza of the capital and once the ceremonial heart of Tenochtitlan at the height of the Aztec civilization, the fewer jacaranda trees you’ll see.

This year the jacaranda is early. On Valentine’s Day, a paroxysm of purple explodes outside the National Palace in the form of a crowd of demonstrating women. The scarves and balaclavas over their mouths are an angrier shade than the light blueish-lavender of the jacaranda. “Ni una más,” they chant, brandishing posters and cloth canvases on which they have written or stitched the names of other women. Ella Aguilar. Fernanda Sánchez. Diana Velasquez. One name appears repeatedly, accompanied by the photograph of a smiling young woman with bright eyes: Ingrid Escamilla.

The weekend before the protests, Ingrid was brutally murdered by her partner, who skinned her corpse and discarded her organs in a drain. At the crime scene, the Mexican police took photographs of her mutilated body. These were leaked to the tabloid Pásala, under the headline: “It was Cupid’s fault.” Ingrid was twenty-five. In an interview with CNN, a representative from the National Institute of Women lambasted the distribution of the images of Ingrid’s body as an egregious example of how violence against women is constantly rendered banal and inconsequential.

Protests like these are common in Mexico. In 2016, the “violet spring” saw tens of thousands of purple-clad women pour into streets all around the country, taking a stand against the malaise of apathy that permeates public discourse surrounding femicide. Similar movements have been organized year after year ever since. The videos and photographs from these events are visually strident. They show livid eyes flashing behind purple scarves, sprawling banners that decry the multiple failures of the state to protect its women, mothers and sisters.

Amidst these vignettes of fury and hopelessness, one particular scene recurs. The women demonstrating hold up oversized white pañuelos, on which the names and stories of slain women have been embroidered. Brenda Tlatelpa Mora, 20 years old, originally from San Pablo del Monte, Tlaxcala, was strangled. Her body was found in a hotel room in Tepeaca, Puebla. The purple messages are as delicate as the petals of the jacaranda flower, connecting the dead to the living in silent sisterhood.

***

María Fernanda Segura Ruiz. I am 19 years old. I was going by public transport to my entrance exam at the polytechnic. I was shot in the early hours of the morning. There are no witnesses. No-one responsible has been detained.

These words are stitched in pale violet on a diaphanous piece of cloth: an indictment, a reproach, the record of a spectral voice. In a café in the Navarte Poniente district of Mexico City, Minerva Valenzuela folds the cloth carefully and returns it to her backpack. Embroidery, she tells me, is similar to respiration. “The needle goes in and out of the cloth, like inhaling and exhaling. I think about the physical space that the words occupy on the cloth. The breath that was ripped from a woman in a matter of seconds becomes material, something we can feel with our fingers.”

The mainstream press in Mexico reported Maria Fernanda’s murder in July 2019. There are thousands of others like her. The Mexican penal code was amended in 2011 to include a separate definition for femicide, and to appease public outrage over the unsolved murders of nearly four hundred women in the border city of Ciudad Juárez dating back to the late 1990s.

Bodies constantly surface, violated, with degrading injuries. They are desecrated and displayed in public places. Investigations have also revealed that women are often stalked for months before being kidnapped, assaulted, and killed. I am sitting at the café with Minerva and two other women, who I shall call Athena and Bruna. All three are members of Bordamos Feminicidios, a collective of craftist guerrillas founded by Minerva, who also works as a burlesque dancer and instructor. Based in Mexico City, Bordamos Feminicidios is determined to confront those who do not take femicide seriously, who have willfully looked away while women die. Using needles, thread, and any white handkerchief they can find, Bordamos Feminicidios honors slain women by embroidering haunting memorials to each of them. The members take these handkerchiefs with them when they travel around the country to participate in large-scale protests denouncing violence against women. At each protest, the handkerchiefs are stitched together, a sprawling brocade of sins that have not been answered for.

Solidarity is infectious. It often catches women unaware, when they’re in transit. A few months ago, a young woman was embroidering in the subway en route to a Bordamos Feminicidios meeting when she struck up a conversation with another commuter. “The second girl came along to the meeting,” Athena laughs. “She had no idea how to embroider, but that’s not important. Some never touched a needle until they joined us. The point of this collective is not to make pretty things.” Athena, in striking blue eyeshadow, is a writer and teacher who runs classes for erotic literature at one of the universities in Mexico City. She found a kindred spirit in Minerva when they met at a burlesque workshop, “dancing around naked like the party animals we are.” This was in the early years before Bordamos Feminicidios expanded from a small roomful of women to hundreds of embroiderers around the city. Athena became so devoted to the mission of Bordamos Feminicidios that she started organizing her own sessions for her students. Bruna discovered the collective through a feminist workshop she attended at the Museo Memoria y Tolerancia (The Memory and Tolerance Museum), where she works frequently with textiles. It is a grassroots movement that has spread primarily through word-of-mouth.

But after eight years, the sheer ugliness of what Bordamos Feminicidios is forced to confront is beginning to take its toll. “I don’t think what we do has helped,” Minerva says. “Five women were being murdered each day in Mexico in 2011. Now it’s gone up to eleven. It’s very romantic to say we are strong, and that we’re awake. But now, if I even consider that I could change something, I would be frustrated all the time.” In the past, it was easy for people to reach out to her via the Facebook page for the collective. Torrents of derisive and hateful comments, some from media outlets, have since forced her to turn off the messaging function. “If they really want to join us, they will find a way to contact me.”

Minerva still regularly receives case files by email from the Observatorio Ciudadano Nacional del Feminicidio (OCNF), an organization that documents the murders of women and puts pressure on the state to prevent and punish female-targeted violence. The increasingly grotesque nature of the murders makes her sick. She began noticing that there are certain patterns in the femicides, not all of which she can explain. In the weeks after female-led protests, for example those for reproductive rights, there always appears to be a spike in the number of women killed, typically by partners or men they shared their lives with. These are epidemics of male vengeance. Other times she has found phenomena that are sinister and baffling in equal measure: “In one week, I hear about four different women being killed, all of them called Veronica Lopez. I mean… what the hell is going on here?”

***

There are only three basic requirements to be part of Bordamos Feminicidios, and for Minerva to assign you a story to embroider. First, the embroiderer must tell the narrative in first person. “I want them,” she says, “to really try and imagine the life of this woman, who we only know in her last moments.” To honor her is to build a profound empathy with the fantasy of a life fuller and more complex than a broken body. Second, the embroidery should be done on a pañuelo, a standard white handkerchief, though Minerva has begun allowing deviations to this rule, because she finds it endearing when the embroiderers add personal touches to their work. “I have received tablecloths or fabric of all shapes and sizes, stained with coffee and wine, with little cats and flowers sewn into the bottom,” she says. “I love it. It means that these women are working on the embroidery everywhere and whenever they can, and the decorative details are like little kisses to the deceased.” The third rule, she says, is that the words must be in purple.

Transforming craft into an act of protest against indifference, against the lack of willpower to reverse or address a societal ill, is something that Mexican women, and women around the world, are familiar with. For centuries both in reality and the literary imagination, women have been the faithful scribes of tales revealing personal and social resistance to injustice or oppression. They did not do this with pens, or quills, or rigid implements that were good for scratching script onto stone—all of these were traditionally believed to be instruments that wielded real power in the realm of the public, where only men’s words counted. Instead women spoke through the objects they had created with their hands, some of which would never cross the threshold of the home.

At times, it was not the actual item that was a symbol of protest, but the act of making or even unmaking it. In Homer’s Odyssey, Penelope eschews the advances of the lascivious suitors encroaching on her during her husband’s absence by telling them that she will select a worthy replacement for him, but only after she has finished weaving a shroud for her father-in-law. In the day she works on the shroud, but at night she secretly undoes it again, because the men have no idea how long it takes to make a shroud. This goes on for three years, until one of her maids betrays her. It is a wily, elaborate way for a woman to say no.

Greek mythology also presented us with the sisters Procne and Philomela. Procne is married to Tereus, king of Thrace, but he desires her sister instead. He rapes her and cuts off her tongue to prevent her from telling anyone else what had happened. Refusing to be silenced, she tells her story through a tapestry that she weaves, and gives it to Philomela.

In more recent history, the British suffragettes wove and knitted militantly as they attempted to mobilize support for the women’s vote. Janie Terrero was a suffragist belonging to the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), and one of the over 1,000 women incarcerated at the Royal Holloway prison from the early 1900s to the beginning of the First World War for their participation in the movement. While on a hunger strike in 1912, Terrero embroidered the names of the women in her cell block, including herself, who were fed by force and subjected to other demeaning violations. At the top of the handkerchief, in purple, she stitched the words “WSPU: Deeds not Words.” Other women were to follow, soundlessly recording their experiences of jail time using simple textiles. Ironically, they were probably allowed to do so directly under the noses of the guards who watched them because women’s craft was felt to be innocuous and benign.

Latin American history is replete with craft-led protests. During the worst years of the Pinochet dictatorship, when Chileans regularly vanished without a trace or ended up in detention centers, hauled from their homes in the middle of the night, the women assiduously embroidered arpilleras—colorful patchwork made from scraps of burlap—depicting the horrors being unleashed by the military police. One arpillera features three people sitting at a dinner table, with a question mark stitched into an empty seat. A portrait of a man hangs above the seat, with the words “¿Dónde están?” floating above him in accusing block letters. Another shows women looking on as soldiers in green uniforms herd the men into vans. The majority of the women in the arpillera movement were from working class families, who had no access to legal advice or a listening ear. They hid their work in their purses and sneaked them abroad as evidence to the world of what was happening in Chile.

The domestic arts, despite often being devalued and belittled, have always been a means of expressing anger at the tears in social fabric, of articulating hope that these tears can be sewn shut.

***

There are conflicting accounts of how the jacaranda, not being native to Mexico, suddenly became a mainstay of the country’s urban landscapes at the beginning of the 20th century. Some say that the trees arrived from Brazil through the harbor in Veracruz. Five hundred years ago, Veracruz was the site of one of the earliest Aztec encounters with the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés. Saying that his people were “stricken by a disease of the heart that can only be cured by gold,” Cortes led his crew of conquistadors on a trek from Veracruz to modern-day Mexico City. His journey paved the way for Spanish explorers, driven by the same febrile desire for the expansion of empire. Some went as far north as California, which was, to their chagrin, not as easily exploitable in terms of natural resources.

But others went in the opposite direction to the southern state of Oaxaca, where the indigenous Mixtec people wore dresses in a vivid shade of purple. The Spaniards noticed that the men had purple-stained fingers and nails. Accompanying them on a march to the coast some three hundred kilometers away, the colonizers were astonished to see them climb onto the rocks by the sea, prying out snails that had been washed into the crevices. Tixinda, the Mixtec called them. They laid them out with quiet reverence on the shore, gently rubbing the bellies of these snails. This induced a white liquid which, when exposed to the sun, quickly turned green and then purple. Rubbing the liquid onto the yarn that they had brought with them, the men then returned the snails to the sea and made the arduous walk home. The Mixtec women made quick work of these purple threads, weaving them into clothes, rugs and purses.

Entire Mixtec villages were decimated by overwork, and by smallpox and other diseases that the Spaniards brought. Eduardo Galeano, the Uruguayan journalist and writer, suggests in his seminal work Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent that the native people of the Americas totaled “no less than 70 million” before the arrival of the conquistadors. One-hundred-fifty years later, only 3.5 million of them were left.

Onwards of 1531, the uprisings against Spanish rule in Mexico increased and were ruthlessly quelled. At each of these insurgencies, the Mixtec, along with other indigenous women, were likely to have been wearing huipil, the traditional garment that continues to be worn today. These huipil bore ornately embroidered geometric patterns, which carried with them the cosmic worldview of an entire people, and which came to life in variegated colours—including the magical purple harvested from the sea. The textile arts became a medium through which sacred knowledge that was regarded as profane, and therefore prohibited by the Catholic colonizers, could be passed down covertly through the generations.

In this way, embroidered clothing became an indelible mark of resistance against the erosion of ethno-religious identity. Over time, embroidery became the accepted vernacular for the condemnation of unchecked power and impunity, and to remember the names of rebels, activists, fighters, and journalists who had been killed in the course of their work. And now, Mexican women are stitching together a collective appeal for justice.

***

Bruna says she remembers every story that she has embroidered, because she takes great pains to research them. In comparison with Minerva and Athena, who were expressive in their outrage, sadness, and humor, Bruna took slightly longer to speak. She grew up with a “very macho” father and brothers, and gradually realized as she got older that the sort of swaggering braggadocio that she had become accustomed to might not be healthy, either for men or for women, “because we have it drummed into us that this is the only way we can live.” After she started working at the Museo Memoria y Tolerancia, she had the opportunity to organize and participate in female-led events and exhibitions. This, she says, was the inception of her feminist awakening, and in the last five years she began researching women’s groups to be involved in.

Shortly after she joined Bordamos Feminicidios, Bruna requested to embroider a pañuelo for Angelina, a woman she knew, a murder that had not been covered by the Mexican media. Angelina was the daughter of Bruna’s mother’s best friend, and she saw her habitually at parties and other social gatherings. “She was forty-one, doing really well in life, was working for the civil service and had just bought an apartment. I felt like I knew her better than I actually did, because my mother would speak glowingly of her,” Bruna says. Two years ago, Angelina was murdered in her apartment by a man she had been seeing briefly. No further details about her death are known: the family never spoke about it to anyone else. Embroidering the date and circumstances of Angelina’s death, Bruna maintains, is her way of “making a memory.”

“It’s still difficult,” she continues after a long pause. “Some of the members of my family—including my older sister—disapprove of what I do with Bordamos Feminicidios, or don’t get why I want to be part of it. But my younger sister has learnt a lot, and is asking me all these questions about the fight for women’s rights in this country. I have been to protests with Bordamos Feminicidios where little girls, no more than ten years old, are curious about what we do. I wish that other women who don’t think that the issue of femicide is important would see that we are all sisters at the end of the day. We face the exact same problems whether we’re out on the street or at home.” Being a member of the collective, Bruna reflects, has made her feel much less alone.

The woman that Athena remembers most is one whose face has lingered in her mind for years. “I recall very distinctly that it was a regular Monday, and I had received an internal bulletin at the university, one of those leaflets that you read and then left for someone else. There was a news item about a girl who had gotten a perfect score in her admissions examination, who was planning to choose chemistry for her undergraduate degree. I don’t think there has been another example in recent history where someone scored full marks—you have to understand that this is incredibly rare, close to impossible. I looked at her face and I thought, you are a genius, you are going to go on to do great things. Two months later, she was killed. Again, nobody ever found out what happened exactly.” Her face crumples. “I will never know her. We will never be able to do anything about it.”

As for Minerva herself, the spectre of Darcy Losada—the girl who worked in the ice cream shop—has followed her to the present. “I saw her all the time,” she smiles sadly. The stories of sex workers who were killed move her the most, because people seem to care less about them, because they haven’t “lived in a way that society thinks is correct.”

Having to remember those that everyone else is bent on forgetting is emotionally strenuous for the women of Bordamos Feminicidios. Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador has appeared to lose patience when asked about the femicide crisis, snapping at reporters that the issue had been “manipulated by the media.” He has also insinuated that the protests were politically motivated to hurt his government. The implied sentiment—which is shared by a significant percentage of the population—is that femicide is not a priority, and that the women protesting are public nuisances who will eventually tire and retreat. Violence against women has surged since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. López Obrador’s reaction was to implement a 75 percent budget cut for the federal women’s institute, with further plans to slash state funding for women’s shelters.

“We don’t deal with it,” Athena finally says. “We just live through it. I write about it—mostly poetry about femicide, for example, but I would never write about femicide for theatre or for a novel. I seldom talk about it in therapy, I talk about it with my friends, I talk about it with my granny who’s ninety-three, and sometimes I cry and fight with my wife about it. She worries about me whenever I go off to a demonstration, and she’s scared that I could be arrested, raped, or kidnapped. Because these are all things that could happen to women, even if you do everything right, whether you’re ’good’ or a whore. I received a death threat in my mailbox at university a few years back. But I’m doing this because I want someone else to not have to do it. What we do is not to manage, to control, or to get over it. I don’t want this anger to fade away, until I have something else to talk about.”

***

In a small bar in the Colonia Juárez district, an illustration of a living room with two sofas and a kitschy “love” sign has been projected onto the wall above the stage, which is flanked by two red curtains. The bar is packed. Minerva’s mother, who sports a cool bouffant of blue hair, is there to cheer her on. The audience dissolves into raucous glee when Minerva starts to sing a medley of well-known Mexican love songs. She bounces across the floor, holding out the microphone to various individuals. She casually sips from someone’s glass of wine and wiggles her bottom. She looks radiant.

I think about something Athena said about her friendship with Minerva and what they both do at Bordamos Feminicidios. “Minerva and I have a special connection in that we’re both cocky, and we admire each other a lot. But our relationship has also changed over the years,” she mused. “It gave me a notion of searching for something together. We’re not just friends: we’re looking for the same kind of world, even if it doesn’t exist yet, or never will exist. Now I have someone to do something with that seems completely meaningless, because we create that meaning together.”