In 1996, fifteen years after its seismic launch, American television network and cultural kingmaker MTV surprised viewers and skeptics alike with an untypical announcement: it was hosting a fiction-writing contest.

Embarking on a new creative endeavour was not, in and of itself, unique to the brand. After all, MTV’s very existence was born from a brazen experiment uniting popular music, visual culture, and a brassy, free-swinging attitude. By the mid-nineties, the brand’s reach had unfurled in a variety of directions—often adjacent to music culture, but by no means focused on it—perhaps most famously those of animated programming (Beavis and Butthead, Æon Flux) and reality television (The Real World, Road Rules).

But literature is a domain often regarded, however snobbishly, as antithetical to the sorts of stimulations available on MTV. What’s more, the lofty, cerebral associations of the written word did not align with the channel’s bawdy reputation. The knowingly provocative music video for Duran Duran’s 1981 single “Girls on Film” initiated what critics regarded as a catalogue of garish smut. As early as 1983, journalist Steven Levy described MTV in a Rolling Stone cover story as “the ultimate junk culture triumph.” The channel won a Peabody Award for its 1992 “Choose or Lose” programming, which sought to mobilize young voters, and succeeded in its aim—at MTV’s inaugural ball, newly elected president Bill Clinton declared, “I think everybody here knows that MTV had a lot to do with the Clinton–Gore victory.” Still, the channel’s efforts to achieve something so serious as heightened political awareness were widely lampooned.

But MTV did not cower before mockery. And though its faltering start augured an uncertain future, the brand’s imprint, MTV Books, ultimately captured the hearts of its target audience of elder millennials who kept their dog-eared copies of The Perks of Being a Wallflower close and lovingly at hand. I was among them. A fickle fan of MTV’s television programming, I wondered whether MTV Books could offer me the nourishment I only occasionally found in the channel’s prodigiously splashy media. It did. And, in so doing, it secured my allegiance to that hell-raising colossus that loomed at the back of my generation. MTV Books was the MTV I wanted.

***

Together with its cosponsor, Pocket Books—the entity through which MTV would found its own literary imprint—the music entertainment behemoth solicited entries for “The Write Stuff” from aspiring, yet heretofore unknown, writers. The contest winner would sign the inaugural MTV Books contract, launch the imprint with their debut novel, and reap a $5,000 advance in the process.

In the twenty-first century, these spoils might seem meagre, even exploitative, but a book contract, especially one tethered to such mighty commercial influence, is a seductive prospect for any labouring writer. So too is fame—and this MTV intimately understood. To qualify, “The Write Stuff” entrants were required to submit three chapters from a work in progress and be under the age of twenty-four. The latter stipulation accommodated the brand’s glorifying emphasis on youth and youth’s weightiest and most cutting-edge preoccupations. In other words, MTV was in the market for prose that aligned with its programming, so predominantly focused on the tangled, horny sociality of kids coming of age in the nineties, like the contestants on Road Rules or, when the animated sitcom premiered in 1997, Daria. Maybe the characters of a future MTV Books title watched MTV—if they had cable television, that is—or maybe they thought MTV was garbage. Regardless, targeting teens and early twenty-somethings made it more likely that the submitted manuscripts would express the current milieu.

But whether due to lack of access or disinclination, the so-called “MTV Generation” hesitated to participate; at first, turnout for the “The Write Stuff” languished at two hundred entries. As the deadline neared, the New York Times ran a short article about the contest which noted, with mild derision, the shallow pool of manuscripts. “It is a truth universally acknowledged that every misunderstood youth must be in want of a publisher. Or is it?” the piece asks, as if with eyebrows raised. Then-MTV executive Van Toffler expressed a similarly detached bemusement. “Apparently they’re taking their time,” he told the Times. “There’s no denying it. Literature is not the most popular art form with our audience.” The adolescents and young adults of the mid-nineties—the audience in question—had long been maligned with the rest of Generation X as inert and intellectually disengaged. Writes Jonathon I. Oake in his 2004 article “Reality Bites and Generation X as Spectator,” “Thus, the deviance of Xer subculture lies in its perverse privileging of ‘watching’ over ‘doing’. . . Xer identity is presided over by the trope of the ‘slacker’: the indolent, apathetic, couch-dwelling TV addict.” The prevailing assumption—accurate or not—was that young, would-be literary stars were too busy watching MTV to pick up a pen.

Tepid press is press nonetheless. Despite its brevity, and its equivocations, the Times write-up must have roused interest in MTV’s new venture. Ultimately, “The Write Stuff” yielded over five hundred manuscripts, and Robin Troy, a 24-year-old Harvard graduate, was named the winner. Connecticut-raised Troy’s debut novel, Floating, imagines a dinky, dusty town in Arizona where its comely protagonist, Ruby, falls in love with her husband’s estranged, cowboy brother. One might imagine it adapted for late night on The WB, after Dawson’s Creek, Tiffani Amber Theissen and Skeet Ulrich smoldering against a sunset.

Surely MTV Books hoped, as any imprint would, that its first title would be met with a warm reception. But when Floating was published in October 1998, it and, by extension, MTV Books, inspired brittle critique. “One of the differences between cake recipes and novels is the greater likelihood of actually getting a decent recipe from a contest,” begins Kirkus’s trade review. Individual critics were similarly grim. “If this is the future of fiction, bring on the music videos,” writes Patrick Sullivan for the Sonoma County Independent.

Sullivan’s review, devastating in its sneering dismissal of Troy’s book, also insinuates that MTV’s primary cultural contributions are too feeble to portend the brand’s success in the intellectually elevated domain of book publishing. In fact, he likens Floating to a music video, referring to it as “its literary equivalent . . . full of quick cuts and perspective changes.” Whatever its accuracy, this comparison heaves with the weight of MTV’s spotted reputation, one that largely turned on the critical response to their music videos. As early as 1984, video director John Scarlett-Davis belittled the channel’s main fare as “masturbation fantasies for middle America.” Many agreed with his assessment and claimed to be repulsed by the videos’ reliance on sexed-up, scantily clad women and the broadcasting of so-called loose morals. In 1998, MTV’s viewers thirsted for replays of Brandy and Monica’s music video for their chart-topping duet, “The Boy Is Mine,” and teenyboppers panted after a glimpse of NSYNC or the Backstreet Boys as they hopped and thrusted through their choreography—but as is so often the case, this searing popularity did not coincide with highbrow assignation. If Floating’s structural template was an MTV music video, it was doomed to sink.

Yet Troy is not to blame for this fumbled literary entrée, insists the Kirkus reviewer, who nonetheless sinks their teeth into the book and leaves puncture wounds. Rather, it is MTV Books who is responsible for sending “this novel-like object” into the world and perhaps “[devastating] any ambition [Troy] might have had.” By sharing her debut with that of the MTV Books imprint, Troy shouldered a prodigious burden. Implicit in Sullivan’s review is the belief that MTV had trespassed into territory beyond its expertise, dabbling wantonly where more robust powers of creative discernment were required. As the first expression of this breach, Troy’s work was bound to attract skeptical scrutiny—when, indeed, it garnered notice at all (Floating, like so many other books written for young readers, did not receive much critical attention).

The shortcomings of any novel can be wielded as evidence of larger lamentable trends; this sort of intellectual synthesis is an expected function of literary criticism. If Floating was regarded as the crude effort of an undeveloped writer, it doubled as a symptom of MTV’s thought-annihilating influence on literature. In Sullivan’s estimation, MTV Books was not so much committed to telling stories as it was concerned with perpetuating its brand aesthetic. “As a physical object, Floating seems designed to provoke the same reaction as a stuffed animal (or a Backstreet Boy),” he writes. “The book is little, it’s funky looking, but most of all, it’s terribly cute. The chapters are all roughly ten pages long (just about right for perusal during a lengthy commercial interruption).” Rather than existing for its own sake—for the sake of a narrative, and for the possibilities exclusive to writerly craft—Floating seemed designed to complement MTV’s programming. Perhaps MTV earnestly hoped to encourage the habit of reading, so long as the practice did not infringe upon its raison d’être, that is to say, televised programming.

But how much influence did MTV expect to brandish when it came to young readers’ literary interests? The success or failure of one book cannot predict the life trajectory of an imprint. If Floating’s prickly reception was not auspicious, surely it did not indicate doom, or anything else, for that matter. Readerly attention is finicky; so is the ebb and flow of cultural preoccupations. As a result, meteoric success eludes most published books, whatever their flaws or strengths. Floating might have been more elegantly crafted—and it might not have mattered.

***

Then, on February 1, 1999, MTV Books published The Perks of Being a Wallflower, a slender, epistolary novel by debut novelist and screenwriter, Stephen Chbosky. And whether due to the narrative’s easy resonance with many among the MTV viewer set—the main characters are white, suburban high school students—the intimacy of its language, or some unquantifiable alchemy, it was a hit. To date, Perks is MTV Books’s best-selling title, and the most recognizable of the imprint’s nearly forty novels and short fiction collections. Rapid, fervent popularity amongst teenage readers fostered robust circulation; by October 2000, MTV Books was printing Perks’ hundred-thousandth copy. And twinned rivulets of momentum, cult readership and educator enthusiasm, solidified the book’s material success: after the production of a high-profile film adaptation in 2012 and a stint atop the New York Times bestseller list, the title is ubiquitous.

Even without the confidence of hindsight, this commercial success would come as no surprise. Perks emerges from MTV’s crowd of early aughts literature as an eager shepherd, scouting out its flock of pubescent misfits: the guileless, the preemptively jaded, and the rest of us wobbling from one emotional pole to the other. The 2012 film adaptation, written and directed by Chbosky, cemented the book’s stature as a darling among contemporary bildungsromans, although initially, critics did not receive it with unanimous enthusiasm. In fact, Perks’ trade reviews weren’t much better than those lobbed at Floating. Kirkus called it a Salinger “rip-off,” and Publisher’s Weekly accused it of being “trite.”

Then again, the sort of reader who finds Perks “trite” might prefer the irritable machismo of J.D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield. An epistolary novel is structured by the pursuit of human connection, and in the case of Perks, the gesture is unvarnished in its earnest, almost puppyish, hopefulness. Chbosky’s narrator, Charlie, writes to his unnamed recipient—someone he has never met, but has reason to think well of—just as he trepidatiously begins freshman year of high school. Charlie’s only friend has recently died by suicide, and his own experiences of trauma and mental illness are growing evermore unwieldy. He is befriended by two seniors, stepsiblings Sam and Patrick. But as Charlie sinks into the novel joy of these intimacies, his determination to be an attentive and loving friend churns with a twinned, subterranean urge for self-obliteration. As a character, Charlie is emotionally generous, but he also prefers not to think about himself, and to instead commit to passive observation (he is, of course, the titular wallflower). However, this is a coming-of-age novel, and so all that Charlie carefully avoids, he must ultimately confront.

As an adult, I find the novel warm and, at times, rather effortful. At sixteen, I thought it was a perfect triumph—and that, perhaps, is the appraisal that matters more. When teenage me encountered Charlie’s now-famous pronouncement, “I feel infinite,” the words hummed, carrying me to the lip of synesthesia. I received this expression of tranquil, comradely bliss—vague, yet invitingly capacious—as both revelation and yen. The Perks of Being a Wallflower was, in my adolescent estimation, the Rosetta Stone of teenage angst, the Key to All Adolescent Mythologies. And, as its issuer, MTV Books had distinguished itself as a purveyor of unabashed truth.

Charlie’s journey towards self-understanding, strewn as it is with romantic missteps, hallucinogens, and live Rocky Horror Picture Show performances, plausibly coincides with MTV’s carefully cultivated brashness, but his wide-eyed earnestness might, at first, seem at odds with the acerbic cool so central to the brand. Then again, perhaps MTV Books was heeding the zeitgeist’s elevation of things red-heartedly sincere. For, although the nineties are canonically understood in terms of disaffection, many sought respite in softer territory. James Cameron’s Titanic, exultantly melodramatic, debuted in 1997 to near immediate, orgiastic obsession and cleaned up at the following Academy Awards. Céline Dion’s “My Heart Will Go On,” the blockbuster’s suitably extravagant love theme, was inescapable, practically atmospheric. The Billboard Top 100 was flush with similarly impassioned declarations: Elton John’s “Something About the Way You Look Tonight;” Savage Garden’s “Truly, Madly, Deeply;” K-Ci & JoJo’s “All My Life.” In the meantime, America gawked at the scandal surrounding President Bill Clinton’s pungently insincere sex life and the simultaneously public excoriation of Monica Lewinsky: dismal proceedings which perhaps inspired us to scout out sweeter expressions of humanity. With Perks, MTV Books sauntered nearby, pairing coming-of-age sensitivity with of-the-moment stylishness.

***

It would have made sense if, after finishing Perks, I had scouted out more of Chbosky’s work. Once besotted with a literary work, this tends to be a reader’s next move: investigate the author’s back catalogue and nurture a bit of fandom. Granted, Chbosky was a relative newcomer, and in fact, he didn’t publish a second novel until 2019, twenty years after his first (this follow-up, Imaginary Friend, was published by Grand Central Publishing, not MTV Books). In 2002, the results of any research would have been lean. But I confess that I did not seek out more of his writing. Instead, I meandered the aisles of Barnes & Noble in pursuit of more titles from MTV Books, the entity that had delivered Perks’s keen fluorescence into the world. This was the first literary imprint I had ever recognized as such. And although I lacked understanding of the logistics, I was receptive to the whispers of its branding.

Surely my response was no coincidence. In an interview with Variety’s Jonathan Bing, Kara Welsh, then-deputy publisher of Pocket Books, explained that Perks’s success derived partially from the imprint’s kinship with MTV. “It’s a coming-of-age story aimed right at the MTV audience,” she noted. Bing then emphasized the prodigious advertising potential generated by such porous boundaries. “MTV produced an on-air spot for the book,” he explained, “a marketing coup enjoyed by few novels, especially first novels by little-known writers.” Implicit in these remarks by Welsh and Bing is the potency of the MTV trademark and its enticing associations of stylish audacity and cultural relevance.

***

The guiding principle of any brand is this: be distinct, visible, and seductive. The MTV of the early aughts achieved this end. Still unimpeded by Napster and the gradual digitization of music, it reigned as the chaotic angel of entertainment. Its logo was—and still is—unmistakable: the solid loom of the “M” pressed against that hurried, inky dash, “TV.” Every weekday, Total Request Live (TRL) commingled the anticipation of a top-ten countdown with the tomfoolery of celebrity guests. And thanks to the exposure of MTV’s Time Square studio, it whipped Midtown Manhattan into an ecstatic frenzy. The MTV Video Music Awards, MTV’s answer to the Grammys, offered more feral pageantry and commitment to shock. When, in 2001, Britney Spears strutted across stage with the thick rope of an albino snake draped across her shoulders, viewers spoke of little else.

I can’t recall whether I watched Britney’s performance on the night that it aired; my television privileges were spare and strictly monitored. But as an elder millennial living in suburban Virginia, I harboured an abiding influence in MTV’s programming events, like The MTV Video Music Awards, or a thrilling celebrity guest appearance on TRL. If I was home alone, I would turn on the channel in search of boy bands and Daria reruns. And if the programming ever seemed crass, absurd, or try-hard, well, I was captive nonetheless. MTV enjoyed a near-monopoly on American music television (with the exception of its more benign sister channel, VH1). If one wanted to hear the buzziest hits, and if the radio felt too unpredictably curated or one-dimensional, MTV prevailed as a brash sensory playground.

Of course, my peers and I complained about its provisions. The music was redundant and vanishingly deprioritized; Carson Daly presided over TRL like an amiable automaton set to power-save. And by the early aughts, happening upon a spate of music videos felt as rare as a sighting of NSYNC and the Backstreet Boys in the same room. As Amanda Ann Klein writes in Millennials Killed the Video Star, MTV gradually supplanted music videos with reality shows like Laguna Beach and Jersey Shore: Family Vacation. Market research suggested that “millennials wanted to be a part of the media they consumed.” If this was my generation’s majority opinion, then I heartily dissented. Above all else, I chased the music video’s walloping glut of sound and fleeting images.

And despite increasingly paltry offerings, I continued to watch. For a cloistered high school junior, MTV—even this diminished iteration of it—signified worldliness. Its programming instructed me in how to be young and how to pretend I enjoyed it. MTV Books piqued my interest because they had published Perks, but my curiosity was amplified by their affiliation with this popular culture juggernaut whose material endorsements guided my hand and my babysitting cash.

For despite my quibbles with their early aughts lineup, I loved MTV. My musical tastes were sufficiently omnivorous to be satisfied by TRL; I knew that Tori Amos and Smashing Pumpkins weren’t likely to gain airplay, but Shakira and Britney Spears would. When, in 2000, MTV broadcasted their first feature-length film, 2gether—a satirical rendering of the boy band phenomenon perpetuated by the channel—it was an urgent cinematic affair. And although I doubted that Daria Morgendorffer and Jane Lane would have given me the time of day, I admired the animated series as the epitome of perspicacious wit.

Surely, then, an MTV literary venture would unite good storytelling with a youthful, uniquely de nos jours attitude. Perks bore out this hypothesis, and so I was motivated to follow the thread. Over the years, I had consumed a healthy dose of young adult literature; although, in 2002, that taxonomy was not so ubiquitous, at least not among my peers. (Yet American librarians have been referring to adolescents as “young adults” since the 1940s, and the term “YA literature” has long been in circulation.) There was no shortage of decent—albeit homogenous—writing for and about adolescents when MTV Books launched in 1998. And while I treated my copy of Perks with attentive ardour, it had never previously felt necessary to read about modern life in order to locate emotional or dispositional familiarity. Why had MTV Books turned my head?

At the risk of ellipticity—because MTV turned heads.

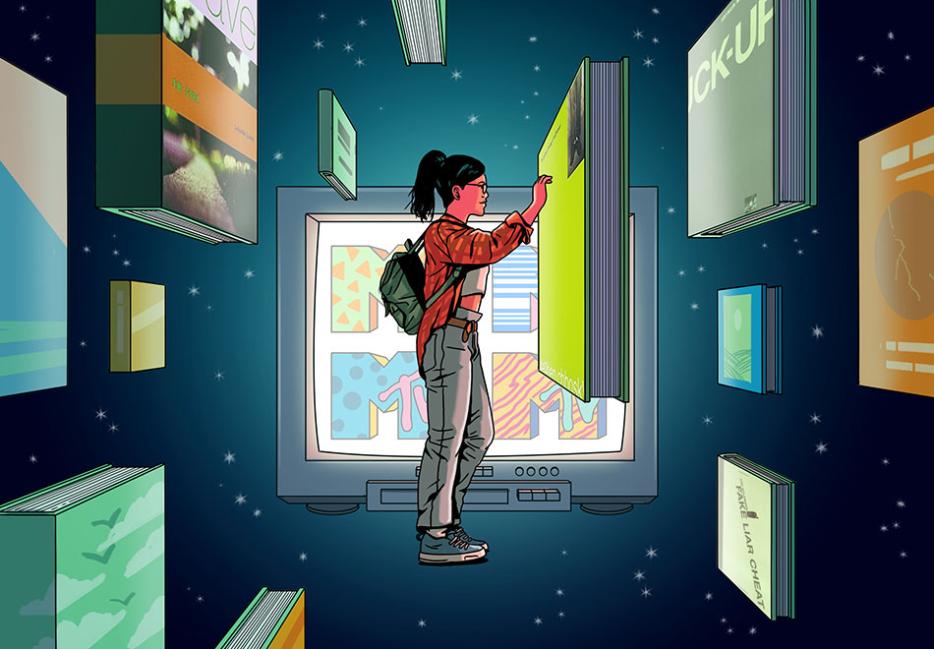

The allure of MTV Books was always, to some extent, aesthetic. And it’s not surprising that an imprint with MTV’s influential heft would understand the craft of packaging. As their name suggests, Pocket Books creates mass-market paperbacks, soft and easily tucked in a coat. MTV Books’ offerings were designed according to this model, and in the years following the imprint’s launch, they manifested a reliable artistic calling card: candid, lowercase typeface, thick monochromatic blocks, and scraps of imagery loosely relevant to the narrative. They were “perfect for sliding into your messenger bag clad with pins and patches,” recounts one of my high school classmates, a fellow elder millennial. Any book can be wielded as an accessory, but MTV’s paperbacks complemented a particular look, one that was punky and chic. And for someone like me, hapless in her polo shirts and humdrum shoes, they supplied an air of subversion. The irony of this—brandishing slickly designed, commercial paperbacks to adopt a more alternative posture—sailed over my tidy, pony-tailed head. Teenage rebel I decidedly was not; subversion only interested me if I could practice it in good company. MTV seemed to assure me that I was. Although its fiction traded in misfits—Perks’s Charlie, Brave New Girl’s Doreen, the titular Fuck-Up—MTV Books was offering its alienated readers a means of fitting in.

What a heady, beguiling paradox: come as you are, and you can be like us. I was addicted to the possibility of belonging and resonance, particularly when it was stained with rebellious aspirations. Relatability is more pleasant when it rhymes with validation, when the person on the page reminds us of ourselves, if only we were more audacious or capable of poignancy at the most cinematic moments.

Hungry for that poignancy, we lonely millennial readers chased the unruly narrators of MTV Books. Narrators who listened to The Smiths and The Pixies, who wielded “fuck” with confidence, and who pontificated self-seriously the way we did on LiveJournal. Narrators who were existentially stymied and frustrated and bewildered by eros. Narrators who were emotionally bruised, who had survived traumas that, perhaps, vibrated in time with our own. Narrators who were love-voracious yet flinty, who bore shields of self-sabotage and well-whetted wit. In return, MTV Books hailed us, offering itself as both the drug and the dealer.

***

In recent years, MTV Books has abided, at least publicly, in a quiet lull, without marketing razzle-dazzle or new releases. The imprint’s most recent output was a hardcover edition of Perks commemorating its twentieth anniversary, released in September 2019.

We may, however, be at the lip of an MTV Books renaissance. In January 2021, various literary media outlets broadcast the imprint’s imminent “relaunch,” to be helmed by industry veteran Christian Trimmer.

I confess, I am skeptical. In a cultural milieu brimming with screen-based diversions, how can the brand wield even a portion of its early-aughts might? Does Generation Z want their MTV just as its predecessors did? With the glut of accessible digital media, I’m inclined to say no. What’s more, in a marketplace now flush with YA literature, and so many authors, both seasoned and debut, triumphing within the genre, I wonder how this new iteration of the MTV Books imprint will distinguish itself, tethered as it is to a diminished pop culture giant, a relic of a society oriented towards cable television instead of YouTube and Instagram and TikTok.

***

I discovered MTV Books nearly two decades ago, when my peers and I stood unknowingly at the cusp of a great digital onslaught. But for the time being, we wandered mall food courts and Blockbusters without the truss of a cell phone, and internet activity was oriented around winking AIM chat boxes and legally dubious mp3 downloads.

Dawdling in Barnes & Noble served as another reliable pastime for a bookish teenage girl too callow for parties or heavy petting. My best friend and I would station ourselves there on Friday nights, drawn to the sugary scented hodgepodge of the café’s Starbucks coffee and baked goods and the ready supply of magazines—Cosmopolitan, Glamour, NYLON—which I preferred to read at a distance from my father’s skeptical gaze. But we would also roam the aisles of books, announcing themselves like so many slick, bound promises of intellectual sophistication and worldliness. One evening, mid-meander, no doubt riding the rush of a cinnamon bun the size of my face, I spotted the MTV books; they were housed together, like a serial—The Baby-Sitter’s Club, if Kristy, Mary Anne, and Stacey were soused in cigarette smoke and sexual longing. The early aughts marketing does register as libidinous: it flirts, tosses its hair, and urges starry-eyed obsession. “Like this is the only one,” razzes a bulletin at the back of one paperback, before listing the rest of the imprint’s catalogue. “Don’t even pretend you won’t read more,” teases another.

And to be fair, they had my number. After finishing Perks, I seized upon Louisa Luna’s 2001 novel, Brave New Girl, highlighter in hand. I visited Arthur Nersesian’s The Fuck-Up (1999) on intermittent bookstore visits, eyeing it like a shy girl at the high school dance. I didn’t dare bring it home. Yes, my parents would have reeled at a book entitled The Fuck-Up, but perhaps I was shrinking from an agitating boundary. Did I trust myself with such provocations?

“I don’t feel like putting on MTV because all they play is trash,” narrates Luna’s protagonist, the fourteen-year-old Doreen. Another provocation, lobbed casually, and presumably at the author’s discretion. And yet its placement seems almost fastidious, as if the result of a pointed conversation. MTV hovers like a paternal spectre, insistent on performative accommodation. “We can take Luna’s joke,” they seem to say. “See? Look at us, taking it.”

When I read that line as a girl, I was thunderstruck, even though I understood that this broad-swathed disdain suited Doreen’s character. She likes what she likes (The Pixies and Ted, her only friend) and is unimpressed by the solicitations of mainstream culture. I may have recognized that a behemoth like MTV could tolerate mild ribbing, that the suits in the room harboured no illusions about their motives or their product. Still, it unmoored me, this recognition of permissibility. Louisa Luna could lampoon MTV in a book they championed.

But of course, this cheeky line was hegemonically sanctioned. Rebellion in MTV Books rarely takes too outlandish a shape, and it predominantly manifests in white, middle-class, able-bodied characters who are inevitably more attractive than they perceive themselves to be. Beck, of Rachel Solar-Tuttle’s 2002 novel, Number 6 Fumbles, self-medicates with booze and the company of frat boys, but still dazzles her UPenn professors with papers dashed off at the eleventh hour. In Fake Liar Cheat (2000), Tod Goldberg situates his everyman protagonist, Lonnie, in a bourgeois variation of Bonnie and Clyde—note the rhyme—but events devolve into such outlandish tumult that the narrative reads not so much as an anti-consumerist critique, but rather as the noirish wet dream of an aggrieved office drudge. Alongside Claire, a comely, chameleonic femme fatale, Lonnie frequents glitzy Los Angeles restaurants, dining and then dashing without paying the bill. When, eventually, his sneaky accomplice frames him for murder, there’s little surprise. At base, Fake Liar Cheat is a nihilistic tale for young men who want to have sex with beautiful women and then blame them for ruining their lives.

Like Goldberg’s Lonnie, the unnamed narrator of The Fuck-Up nurtures a diffusive, hyper-masculine dissatisfaction that propels his undoing. He flings himself through 1980s New York City, seemingly hell-bent on bludgeoning his life, but his every predicament arrives after limpidly evident bad choices. Ultimately, he is offered salvation and takes it. MTV Books chronicled all manner of suffering in the early aughts, most of it cruel and undeserved. It was also the suffering of the systemically blessed. Despite the exploits within, these are primly woven stories that deliver snug denouements, implicitly rendering the characters’ subversions controlled and validated, their hardships, if not easily solved, then at least socially legible. Perhaps we ought not be surprised: their packaging—audacious and distinctive yet streamlined and contained—seems to promise these tidy, digestible rebellions. And for MTV Books’ target readership, so vastly dominated by white, upper- and middle-class school kids, this was a digestible, satisfying dosage. Donning the solipsistic lenses of coddled adolescence, resonance and familiarity can easily masquerade as literary virtuosity. A trendy book cover might look like an invitation to a new home, one that feels safer and intrinsically true.

At the start of The Fuck-Up, Nersesian’s narrator—comfortably separated from the novel’s sordid events—briefly appraises the circumstances of his domestic harmony. “Recently we celebrated our seventh anniversary together with a decent dinner and a not dreadful film,” he recounts. The vicissitudes of a placid adulthood: a dinner that tastes good, but not great; a film that entertains but doesn’t transport. This sort of mundanity might send you searching for Charlie’s beatific infinitude—searching, perhaps, in a rowdy little paperback whose logo promises wild delights. And when you’re sixteen and full of ache, you’ll believe in them.