Ever since the first fishing colony on the island was established by the Portuguese explorer João Álvares Fagundes around 1521–22, Cape Breton has long had a special, almost mythical allure. It was the Scottish inventor Alexander Graham Bell who once said: “I travelled around the globe. I have seen the Canadian and American Rockies, the Andes and the Alps, and the Highlands of Scotland; but for simple beauty Cape Breton out rivals them all.” Many like Bell—not to mention thousands of fisherman, miners, and steelworkers—chose to stay, make their homes there, and start families. A thriving tourism industry means the island sees its fair share of tourists too.

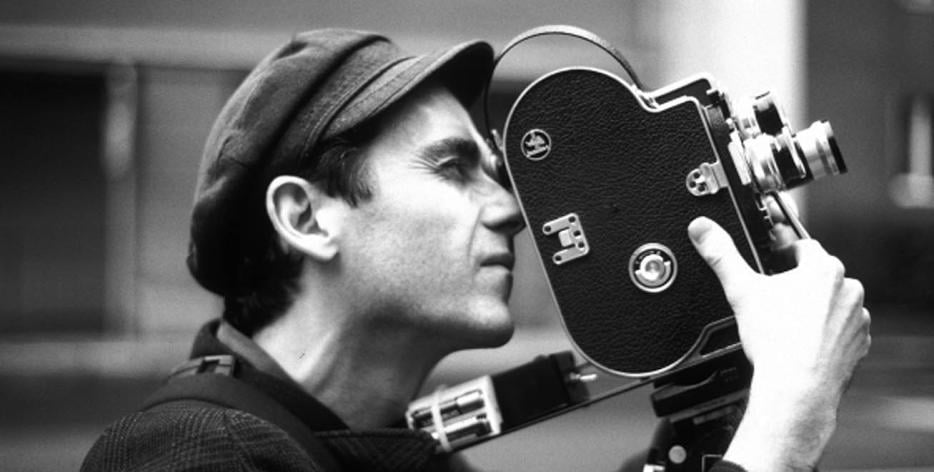

Being an outsider is a feeling that filmmaker Jem Cohen knows only too well. Born in Kabul, Afghanistan, where his father was working for the U.S. Agency for Information and Development, Cohen eventually moved to the U.S. and graduated Connecticut’s Wesleyan University in 1984. Now based in New York City, he’s earned a reputation for innovative, observational portraits of urban life, shooting in formats such as Super 8 and 16 mm, and collaborating with bands such as Fugazi and Dutch anarcho-punks The Ex on music documentaries distinguished by their originality and experimentation.

For We Have An Anchor, Cohen found himself getting out of the city for once, and focusing his lens on the rugged wildness of Cape Breton. Featuring a live score by members of Fugazi, Godspeed You! Black Emperor, and Dirty Three, he first showed the piece in Troy, New York earlier this year. This week Cohen brings it to Toronto's TIFF Bell Lightbox for a two-night engagement presented by the Images Festival, where singer Mary Margaret O’Hara is being added to the musical mix (the second presentation is tonight). He spoke to Hazlitt in Toronto while on a break from rehearsing.

What drew you to Cape Breton in the first place?

I first went to Cape Breton because I was spending a lot of time with Fugazi and working on Instrument [Cohen’s 1999 documentary about the band]. They got a gig playing what I think I heard at the time was a bowling alley, or a former bowling alley, and I just wanted to see Fugazi play in Halifax. I also knew the artists June Leaf and Robert Frank , who live in Cape Breton a lot of the year, so I asked them if I could come say hello. I left Fugazi behind, drove up to the island on my own and I was just blown away by it. So I started coming back whenever I could over the next few years.

I’m from mainland Nova Scotia and even as a child there was a certain mythology to Cape Breton. I remember going there for the first time, driving over that causeway, and it felt like it was a different world, like it wasn’t part of Canada or even North America. Did you have similar feelings?

Very much so. It’s kind of strange because there’s all that crap around the causeway, that little explosion of cheap restaurants and gas stations, and suddenly you drive across and very quickly things get kind of quiet, but also... I’m trying to find the right word. There’s something about it.

There’s definitely a history of resilience there. I’m wondering if you faced any resentment or difficulty from the locals. Surely not everybody was impressed with you shooting there?

Resentment to the southern barbarian? [laughs] I don’t film with a big crew or apparatus, so mostly I wasn’t noticed. A lot of the people there are dependent on, and simultaneously probably frustrated by, the tourists and summer people and “come-from-aways” as they’re called, and that’s all part of it. I respect that and I didn’t want to be an invasive presence. But on the other hand, we’re all “come-from-aways” somewhere down the line, unless you’re a Micmac [Mi’kmaq], I don’t think you can claim Cape Breton or parts of Nova Scotia as your own.

It’s a very natural thing for people to resent invaders, because very often they underscore disparities of opportunity and wealth, but it’s also true that’s it’s kind of a double-edged sword. People have to be protective of the regional character of where they live, but if they’re so protective that they resent all outside influence then they’re making the mistake of forgetting their own history. I think most of the people associated with Cape Breton regional culture have roots across the drink to Scotland and Ireland. Once upon a time they were newcomers, but it’s a different kind of newcomer then the summer tourists.

I understand that We Have An Anchor uses a lot of found documents like newspaper articles. How did you amass those?

There’s not actually that much of that. Initially I thought that there might be because this a project that would probably take different forms. We did it as an initial work at EMPAC [Experimental Media and Performing Arts Centre at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York] and this is the second iteration of it. And it will change somewhat. If we were to do it again it would become quite different.

But first of all, I wouldn’t call this a film, it’s really somewhere between a film and a concert but it’s neither of those things. It’s created in a given room on a given night and it would never be the same in another room on another night. I would definitely not consider this to be definitive to me in any way. When you make a film, at some point you need to lock the damn thing in and it’s done and it is what it is. This thing is something that I would hope that I’m still working on, so texts will change that I’m using.

I like to spend a certain amount of time just experiencing a place, just keeping my ears and eyes open, and trying to soak in what it feels like. Afterwards when I’m dealing with the footage, I’ll usually do a lot of research, so I’ll read a lot of books and newspaper articles and poems. I get a wide room and try to sweep up as many little fragments of information. That can range from stories that people told me that I encountered when I was there, or it could be a story that somebody told a long time ago, that’s kind of a fable that may or may not be true. They’re just fragments of things that fall in and out of the piece. I think it’s all part of realizing that I’m not making any definitive statement of any kind, it’s a collage, it’s a patchwork.

This isn’t the first time you’ve taken this collage approach to your work. Is that’s something that’s become increasingly difficult in today’s world, when it’s digital this and digital that?

It’s harder and easier. The problem partly is that it’s too easy to do research now because the Internet is so full of it, but I just don’t like to do all my research staring at a computer. That’s another weird thing that’s kind of a mixed blessing, that we can research anything all the time. You used to have to dig a lot deeper, but then it becomes a matter of how you sift through this mountain of overload. In the scheme of things, Cape Breton and Nova Scotia are not the most written about.

Not even in Canada.

No. To me, I’m a city kid for the most part, and when I crossed the Canso causeway and then drove a few hours up, the only thing I’ve experienced even close to it was when I was 12-years-old and I was in Scotland and northern Wales. It just seemed astonishing to me that I could access that on my own continent, but very few people I knew had any awareness of it. There’s that natural beauty that’s nothing to be ashamed of and also something to be really protective of. There’s also lots more going on and a lot of industrial landscape, which is not picturesque and not necessarily welcoming or beautiful in any traditional way, and that has to be reckoned with to. So there will be people that only go around the Cabot Trail and don’t experience parts of Sydney.

Which is a pretty hardscrabble town.

Yeah. And that interests me too. But then again it’s also the kind of thing where you don’t want to assume you can look at the surface of it and really understand it. Even Sydney changed quite radically in the time that I was there.

I was watching Instrument the other day, and there was a part where Ian MacKaye was talking about Fugazi shows, and how they interact with fans. He says that they “don’t want to play just to heads and bodies.” Do you feel that mentality translates to your filmmaking or how you want audiences to react to your work?

Well, I do feel that way. If there’s a tradition that my filmmaking comes out of in a practical sense, it’s a punk rock tradition, because I grew up in D.C. The bands there, and Dischord Records in particular, provided a kind of template of how to create things outside of the industry. My relationship to Hollywood or mainstream cinema is similar to D.C. punk’s relationship to the music industry, which is the music industry didn’t want anything to do with them, and therefore they decided to be their own industry. And it’s a cottage industry, it’s a small industry that tries to celebrate the benefits of not aiming for the biggest of popularity or numbers.

It’s not like [We Have an Anchor] is an interactive experience in the sense where people are voting how it’s going to end on their iPhone using Twitter while they watch it. It’s interactive in the sense that you can present something to people in a way that offers the possibility that they will take their own journey with it. You try to take an approach where you have material that people will react to differently on their own. Sometimes that will be what you’d hope it to be, and sometimes they’ll end up kind of befuddled or feel that their expectations were betrayed. But you just try to make something that has some openness to it.

And something that isn’t necessarily linear.

Right. In the case of this thing, there are sections where I’m really trying to have people experience time, so that they feel the shift of time and that time has different modes. They have to just sit and be quiet for a while sometimes and just let their thoughts wander.

Even when I was doing Instrument about what can be a really loud, intense punk band, we were trying together to create room for thought and contemplation, and for people to have a kind of shifting experience. So that they know a little bit more about what it’s like onstage, but also a little more about the endlessness of parts of the drive or waiting for the load out or whatever. Any given movie is a discussion of time, except usually that discussion is usually pushed to the background and made to be invisible. We’re trying to invite people to have their own and varied engagement with this material.

You’ve worked with many artists over the years, including Elliott Smith and R.E.M.. Do you consider the music videos you did for these artists to be “snapshots in time”?

No, the music videos that I did—I was remarkably lucky in that, with one or two exceptions, I didn’t think of them as music videos. I didn’t want to think of them as music videos, and I still don’t want to think of them as music videos because that’s an industry I just never wanted anything to do with.

You’d rather think of them as vignettes.

I was allowed to make short films and generally with R.E.M., with one exception, I was pretty much told to go off and do my thing and bring it back to them and often the band wasn’t even in it. They were just attempts to reckon with a given song in my own way, they weren’t really playing by what became increasingly restrictive rules of that industry. I just never considered myself a music video director and it makes my stomach hurt whenever I hear somebody say that.

You don’t think very positively of music videos?

There are lots of wonderful things that people have done in the name of the music video, but the wonderful things are a tiny little sliver in the grotesque pie chart of MTV-type videos. It’s just ridiculous that out of the hundreds of thousands of music videos made, the overwhelming majority of them are not only grotesque, but they’re insulting to music. They don’t offer any real experience of music making or music listening, they just basically exist to distract you away from the music towards something else, like towards some image or a clothing line or a record release. It’s not music that they’re about.

Most of the musicians that you’re working with on We Have An Anchor you’ve known for years. Tell me a bit about that process because I imagine it can’t be easy with everybody living in different cities.

No, it’s really, really hard, which is why I don’t necessarily expect that this will happen again. Guy [Picciotto, Fugazi], I’ve known forever, and he’s been a close collaborator on many projects and we’ve spent lots of time in editing rooms together. Todd Griffin, I worked on a lot of soundtrack stuff for my films and a lot of live stuff like this. I’ve done films for over ten years that have contributed to the Godspeed You! Black Emperor live shows. Jim [White, of Dirty Three], I’ve never worked with before, but he’s simply one of my favourite musicians in the world. They’re all musicians who I think are very hard to pin down, they’re all people who...

If I were to pick a defining characteristic that all of these musicians share, I would say that they’re all quite elusive.

Yeah. I think it’s elusive but hopefully it’s also just open. There tend to be worlds that people recognize, like they say, “Oh this is an improv musician, this is a punk band, and this is a classical player.” When I first heard Godspeed, it just made sense to me, what I felt was “Oh these are people who understand why the MC5 was great but who also completely understand why Arvo Pärt was great.” They probably take those things in as equally powerful influences and they’re players who can certainly improvise. Fugazi never played with a set list in any of their years, so that they had to be completely open at any moment to how the air in the room might shift things and go off in some other direction. In this case, a lot of the project for me was about time, experiencing time and thinking about it.

There’s a quote from a geologist in the piece talking about the way that an island exists as a remnant of these massive events that happened with such monumental slowness. We can’t even wrap our mind around it, that the Atlantic Ocean would separate a land mass and that’s why the rocks are doing the same thing on the tip of North America as the edge of Europe, because it’s really the same landmass if you readjust your limited notion of what it means for an event to transpire. If I want to approach some little sense of that on sonic terms, then I need to work with musicians who can kind of warp time. In the years when I would watch Dirty Three shows, I would watch Jim play the drums and I often felt like he was readjusting the clock in the room. It was such a pleasure to bring him into this project where I was trying to do the same thing but it terms of a place. I just really like the possibilities of where people can get really quiet, like everybody’s ears in the room sharpen up like you’re in the wood and you’re trying to hear some little sounds, but then half an hour later it’s a full-on punk rock thing where it’s just heavy. Weather changes, especially in a place like Cape Breton, so why have it be one or the other?