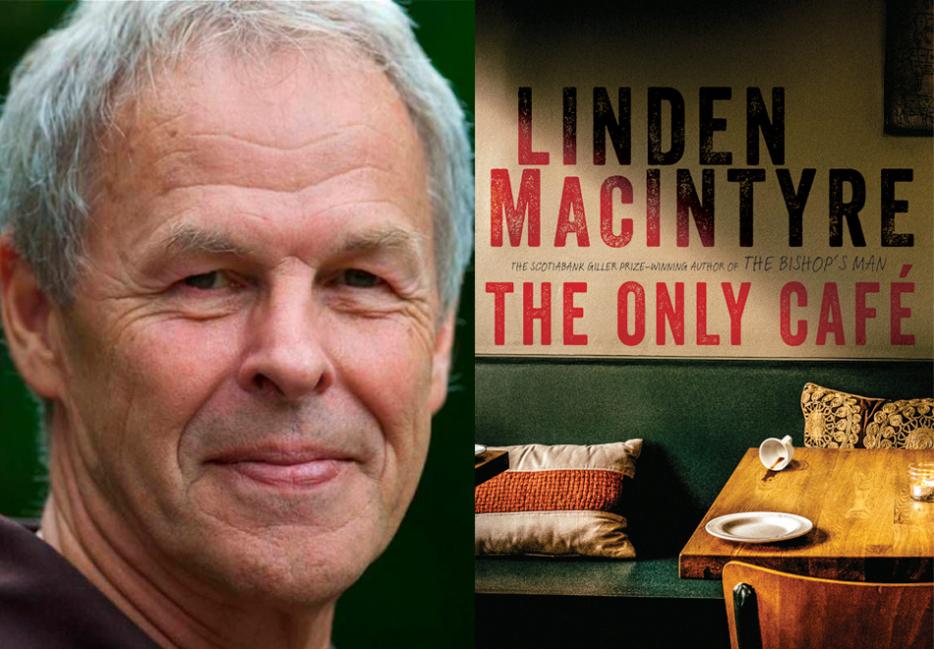

Linden MacIntyre’s The Only Café (Random House Canada) is about failed attempts to forget the past, and the consequences of revisiting territory behind what the novel calls “the memory wall.” The book, McIntyre’s third novel, draws on his on-the-ground experience as a journalist in the 1982 Lebanon War, as well as his later experiences both behind the scenes and in front of the camera as co-host of the CBC’s newsmagazine the fifth estate.

Pierre Cormier, one of the novel’s two protagonists, starts the novel dead—or, at least, vanished. At a reading of his will, his son Cyril discovers that his father has a mysterious connection with a bar in East Toronto called The Only Café, and a much more compelling and mysterious connection to atrocities in the not-so-distant past in Lebanon. Helped—or possibly hindered—by a supposed friend of his father’s named Ari who hangs out at The Only Café, Cyril starts to investigate his father’s past, paralleling Pierre’s own plunge into the past, a journey he made in the months leading up to his disappearance.

Naben Ruthnum: I wasn’t exactly ignorant of the period of history in Lebanon—the 1982 Civil War—that forms the dark backdrop of memory that drives the action in The Only Café, but I certainly wasn’t well-informed. The novel’s story moves while signposting crucial bits of history, ensuring that this reader at least could really follow things. Was it hard to balance this information-giving with storytelling?

Linden MacIntyre: [The balance] just happened, because—for someone who has been there, it’s always surprising—[the Lebanon War] has been in the forefront of my consciousness since the early ‘80s. One assumes that everyone’s been studying it in school, everyone’s as familiar with it today as I was then.

I guess one of the most rewarding aspects of having written this is that it’s opening people to two things. One that this particular event, and this particular civil war, happened, and it was horrifying. And when people become conscious of that, they become conscious that all the other horrors that are going on all around us that everybody right now knows about are part of the same continuum, part of the same dynamic.

It’s not inconceivable that maybe twenty-five, thirty years from now, the ISIS phenomenon, the war in Syria, the war in Iraq—these things that are front and centre in our consciousness today—will be new to another generation. And another generation may have a reason to revisit what’s happening today, and will be further aware of this continuum of history. That was a big part of my education as I grew older: I suddenly realized there was nothing really new. It’s all part of something that was going on before.

Another way you suggest that continuum of history is Pierre’s job: his current-day job working in mining engineering. There’s a violent incident involving local workers in Indonesia entering a conflict with the Canadian company Pierre works for, which projects him back to the past. This happening in the supposed “third world,” has a huge impact on Pierre, and links him to his own memories of where he came from before embarking on his new life in Canada.

I got a little worried that [that section] was getting a complicated thematically, but I realized that it’s just one theme: that violence is universal. If Canadians feel that we are exempted or that we are somehow insulated from it, then we’re deluding ourselves. The Canadian mining industry is working in some extremely violent and precarious places—this event in Indonesia (in the book) is not entirely fictional. I’m aware of a similar situation, involving Canadians. It wasn’t in Indonesia, but it was in that part of the world. It’s a very powerful and influential part of human nature, this tendency to do violent things, to betray our fundamental values and character and engage in violence.

Whether it’s in the behaviour of a corporation in the so-called third world or in a civil war in a place like Syria or Iraq or in Vietnam or Lebanon, there is something in human nature that wants to create horrifying circumstances for other human beings. It’s just one theme: that violence is part of our collective and personal memory. And that violence can become overwhelming when it takes over the memory, and can lead us to very dangerous places.

Pierre has managed to wall off a lot his violent memories until this incident in Indonesia reawakens it. And then a chance encounter in a little bar brings him up really close to his own particular experience, and Pierre somehow thinks “because I’ve shared this experience with this guy, the two of us have a similar and equivalent need to excavate and to get rid of the demons that it left us with.” This is a mistake, because you cannot assume that every memory, even of particular events, has any similarity to someone else’s memory. Pierre doesn’t seem to get it, and keeps pushing the memory, not realizing that what’s past for him is not really past for Ari, the guy he’s trying to draw out.

The whole question of trying to explore the worst memories is usually a healthy impulse we have. But to presume that someone who shares a version of that memory is going to be in sync with you in revisiting it is a perilous proposition.

Something I feel is pretty attuned to these ideas of memory and recurring violence is curiosity—curiosity’s a prominent part of this book, and something I found to be particularly interesting in Cyril, Pierre’s son, who is working a journalism internship as he begins this plunge into his father’s past, prompted by Pierre’s mysterious will. Cyril seems like someone who had stunted curiosity about his father’s background, which is actively kickstarted in his early twenties, at the beginning of this book. What is it that makes him less curious about his dad as a child, and what gets him going once he finds his father’s will?

It’s fairly natural, curiosity—Cyril is a young guy who doesn’t have a great store of memories, and in particular he doesn’t have much memory of his father, who stepped out of his life when he was just a boy. Curiosity is where memory gets born—we become curious about stuff, and as we find things out, as we experience things, motivated by our curiosity, we accumulate memory.

Part of my theory of journalism is that one of the principal assets that a journalist must have is an open-minded curiosity. So Cyril’s curiosity is normal—he’s curious about his dad, who first disappeared into another relationship. And Cyril repressed that initial curiosity by being angry and bitter. But now dad has disappeared, and the curiosity is reborn. Now it’s not enough to just say, “Oh, fucking Dad walked out on us and I’m not going to think about him anymore.” Now there’s a deeper mystery, and it’s a sharpened by the fact that Cyril deep down believes that he’s never going to get the chance to ask questions of his dad again. So that sort of drives him all the more.

Because of the career Cyril’s chosen, this flowering of curiosity also seems linked to him maturing, becoming a man. I thought that was interestingly paralleled with Pierre’s, as it’s brutally phrased in the book, “chemical castration”—the end of his life, in his mind, as a functionally sexual person.

There’s something symbolic about Pierre’s crisis over his health. He’s approaching middle age, and it’s bringing many things into focus about what’s important in his life. It becomes part of the healing process when he’s out on the boat—as I step back from the book and look at these characters as real people, I think that one of the great tragedies is that Pierre reaches an epiphany (toward the end of his storyline). He’s come to terms with his own physical limitations, with the toxicity of his own personal memory, with his new child coming, his great relationship, and knows that he came close to screwing everything up because of his obsession with his memory. But he’s already created his own doom, while he was pursuing this obsession with the worst part of his life.

Anyone who’s ever had to confront the reality of cancer—it’s one of those moments that redefines everything. I had a character in an earlier novel say that “Cancer isn’t just a diagnosis, it’s an announcement.” Everything in your life is about to change. Whether you have serious cancer that’s going to kill you, or you have a curable cancer that’s going to draw you down and through a primal experience of survival, everything changes.

As Ari says in the book, survival has no moral quality. If you survive, you go on; if you don’t, you don’t. We survive, we do things to survive that are not always pretty. We are often the products of the lives of survivors.

Much of The Only Café reads like a spy novel. You’re many books into your career, but when you’re coming to a complex novel like this, with two protagonists, these deceptive and slowly revealed sources of information, and a complex timeline—do you ever go back to any model writers? I was thinking of John le Carré and Graham Greene, for example, when I was reading this. Do you think of the structures of other novels as you construct yours?

Those are two of my favourite writers, actually, particularly in the way they develop character. I think I might well have been influenced by them to come to an understanding of how important it is that the characters you invent take on a reality. So that when they speak, you’re not putting words in their mouths—you’re transcribing what they say. [Le Carré and Greene] are two of the greatest examples of writers who are very good at that. Of course, working in TV for many years, I understand the importance of the human voice, how people talk, coming from a very oral culture. Dialogue, talk, the shape of a story was a key part of the local culture.

I don’t know if there is a model or a place to go to learn how to structure a complicated story. [The Only Café] was a story that sat around in my brain for a long time, and I never had really sat down with a big sheet of paper and sketched out architecture. I had an idea for a story, I had an idea for some characters, for a basic situation. But I knew I was setting myself up for a lot of struggle, by virtue of the fact that it was going to be a mystery story to find out who this guy was and why he was dead. When you have a dead protagonist on page one, you’ve got a challenge. You can’t escape flashbacks, but I wanted to make them relevant, and relate them to an ongoing search by another character.

I can remember a moment when I was out jogging one day, which is always a great way to think. Somehow it releases endorphins that activate the imagination a little bit, this is one of my theories. I suddenly realized that I was going to have to do this book in a fashion that isn’t my favourite form of storytelling: two points of view, two voices, two protagonists. I’m a traditionalist, I prefer one character and one voice, to make it work that way.

There was never a moment in the story where I didn’t know how the next section was going to begin. The one part that was troubling was how I was going to end it—who was going to be left standing?

I was surprised to find that The Only Café was a real place. I live in Toronto, but out in Parkdale, so I’m rarely out east, around the Danforth. But it’s rare to have a real-life place used in a novel where the writer has made slightly sinister associations with it in the plot. Did you run this by the owners? Do you go there?

Oh yeah. I go there quite a bit, and I had those very same thoughts in my head. I asked this bartender there that I knew to set up a meeting with the owner. I sat down with the owner over coffee, and had my presentation in my head—I said, “Look, I’m writing a novel, I want to call it The Only Café.” He said that’s great, and I told him I wanted to put a lot of the action in this place. He said it was fine, and I told him I’d walk him through the story from one end to the other, just to make sure he was comfortable.

He said, “I don’t fuckin’ care what the story is. This is just cool,” drained his coffee and left.