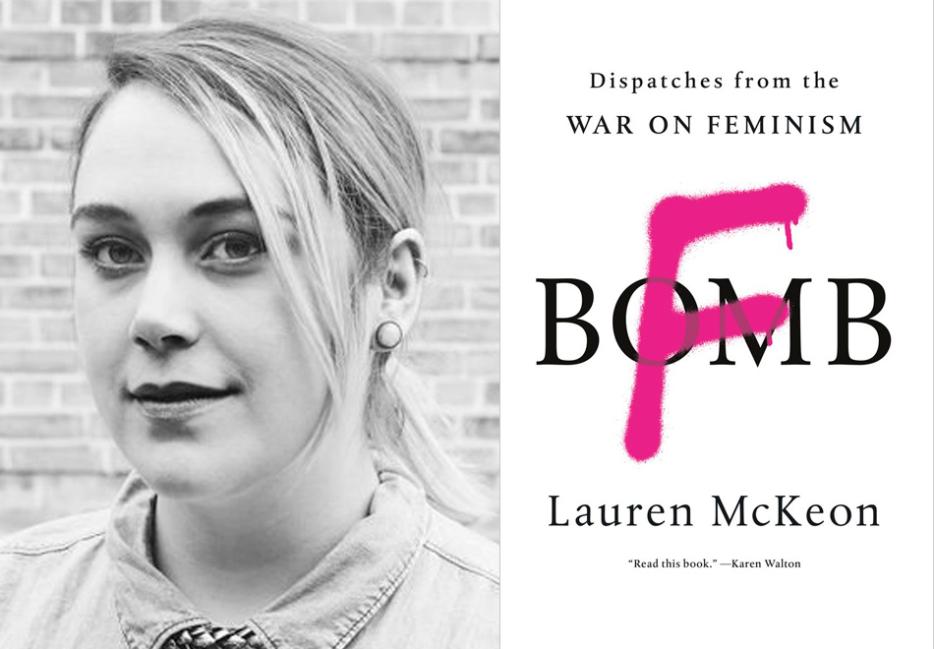

Decades from now, when humans not yet born scroll the archives of feminism in 2017, it will be easy to envision an era of unity—the #womensmarch hashtag on Instagram boasts 1,437,462 tagged photos, “The Future is Female” slogan has re-proliferated everywhere from baby onesies to New York Fashion Week. Women’s marches around the world crammed the streets with feminists of all genders last winter, even men who aren’t actually feminists but say they are because it’s cool for them to do that now. According to Ivanka Trump, her father is a feminist. But as author Lauren McKeon boldly uncovers in F-Bomb: Dispatches from the War on Feminism (Goose Lane Editions), as both a concept and a function, feminism is in pieces.

McKeon, a Toronto-based journalist, spent three years investigating the women-led anti-feminism movement, tracing back to its origins and doggedly interrogating the movement’s current resurgence. Though for as long as there’s been feminism there has been anti-feminism, too, the backlash at the heart of the matter stems from the first wave of the men’s rights movement, which began in the 1970s. MRAs—women among them—“cringed at the idea of women with autonomy” and protested the demasculinization of men, hoping instead to preserve traditional gender roles. “The same rhetoric was re-emerging, only now it was wilder, and, also, everywhere,” writes McKeon of the present day. “Social media allows the ideas underpinning both anti-feminism and post-feminism (the idea that we’re past the need for feminism) to spread and to connect, and the anti-feminist movement—and its many octopus arms—have grown beyond the usual suspects.”

F-Bomb is an awakening for those who believe feminism serves everyone equally. As McKeon notes, there are valid reasons for opting out. But it’s also an alarming peek into the lives of women who fiercely impugn the need for gender equality at all, women who feel feminism has instituted moral panic around rape culture, encouraged the hatred of men and boys, that it has limited women’s potential by portraying them as perpetual victims, that it has interfered with tradition and that it has devalued motherhood.

The book is an intense and enlightening inquisition, not just as a corrective for future generations who will gaze upon the Instagramability of our righteousness, but for those recalibrating the meaning of feminism right now.

Carly Lewis: You write that many feminists, upon learning of your research, questioned your pursuit with a sense of “curiosity akin to a five-year-old studying an especially nasty bug.” I’ll admit that I went into your book feeling… something like that.

Lauren McKeon: I’ve gotten that a lot. By humanizing someone they almost become scarier. I wanted to humanize these people—though I don’t know if humanize is quite the right word—and really talk to them, and see what they were like and what they really believed and why that was. If you think these movements are just full of monsters… well, monsters don’t exist. It’s very easy to dismiss a monster and think that the ideas of monsters won’t connect, that they won’t gain traction and won’t infiltrate policy or thinking or media. It’s harder to grapple with the fact that these people go to their kids’ soccer games and go to book clubs and go to work.

There’s a point in the book where two women tech executives stand in the kitchen of a start-up and deny that the industry has a gender imbalance. You deftly note that their office has more foosball tables than women. What impact did this process have on you personally? Three years is a long time to spend with people who fundamentally oppose your principles, especially when you’re with them as a journalist, not an opponent who can speak freely.

I’d had a hunch that these ideas were bubbling up of course, but it was watching them unfold in real time and seeing how much traction anti-feminist thinking has really gained, and how pervasive it is and how normalized it’s become that made me tired. It also made me curious, and it made me more convinced that we need to shine a spotlight on what’s happening as opposed to trying to pretend it doesn’t exist.

Did you see Tina Fey’s Weekend Update appearance where she suggested that if we just let violent white supremacists tire themselves out in Washington Square Park they’d go away? I understand the machination of compartmentalizing, but doing so in this case seems like giving them permission.

That’s a lot of what we have been doing, just talking amongst ourselves. (I mean people who are progressive.) There’s value in commiserating together, and poking fun at the other side, but at some point we have to realize that there are real effects to what’s going on. We can’t just eat our proverbial cake and hope that it’s going to go away. It’s not as if it came out of nowhere. We shouldn’t have been ignoring it.

Early in the book you write, “Though dissent isn’t inherently terrible, it’s hard to understate how much of it is fracturing us.” How do you write a book like this while knowing it will contribute to the fracture?

It’s so thorny to speak out. By speaking out I could be contributing to the fracture, by speaking out I’m also contributing to the elevation of white women’s voices, by speaking out I’m also shining a spotlight on the alt-right and anti-feminist movements. There are arguments to be made for not doing so. But what I hope the effect of speaking out will be is to present a thoughtful, considered, well-researched argument. I hope that people will continue the discussion. I think that’s what we need right now, to talk more, and to get off of our soapboxes. That’s a lot of what contributes to the fracturing: people want to be right. They don’t necessarily want to listen, and they don’t want to self-reflect. They don’t want to be open to criticism. It’s really hard to get anywhere when that’s happening. We’re in the age of bullshit. People are just bullshitting each other. I hope part of the antidote to that will be having a conversation. And that will mean listening.

I also couldn’t possibly talk about the anti-feminist movement without talking about and self-reflecting on the feminist movement. It’s important for us to do that, too. That’s how feminism itself will grow and become more inclusive and get better and relate to more women. It needs to go through the same process of interrogation.

Are you familiar with Carla Lonzi and the Rivolta Femminile? Lonzi’s ideas were about connection through disparity. There are some parallels between Lonzi and what you’re saying, I think. What were you able to conclude after speaking with so many women whose ideologies did not mirror your own?

This is not an argument that is unique to me, but we need to move toward a plurality of feminism. Women are not monolithic. Feminism can’t be monolithic either. If we allow for that plurality of feminism, we can work apart but together. We’re all affected by the same issues, but we’re not affected equally by those issues. The feminist movement hasn’t done a great job of acknowledging this. We really need to chip away at that. Feminism is going through a round of growing pains right now, and some of that is clumsy and some of that is awkward. But we are moving toward something that’s better. Part of what made me optimistic even after spending a lot of time talking to people who made me worried about our future was talking to other young women, and girls, and seeing where they’re taking the movement and how they’re making it more inclusive. There’s a lot that’s going on that I don’t like, like the mass-marketing of feminism, and how it’s cool to wear a feminist T-shirt but it’s not cool to actually have politics, but there is this new movement that’s being forged by the next generation—it is smart, savvy, inclusive and diverse. That’s just how they see the world. And that makes me feel positive.

I work in arts and culture media, and I am full of joy about the generation of young women writers coming up after mine. Things that it took me ten years to decline on—cowering to misogynistic paternalism, the anxiety of not being liked—they seem to reject right away. I see them advocating for themselves much sooner, which is incredible to behold. I want them to take over. At the same time, I don’t know that I, or we, collectively, have done enough to make the media industry safe for them to inherit.

I agree with you. I don’t know that we have. Part of me wonders if the reason why they’re so good at standing up for themselves is because it’s been thrust upon them. Maybe that’s a cynical way of thinking about it, but in my conversations with teen girls it’s become clear they are dealing with horrible, horrific things—being grabbed in the hallway, having "slut" shouted at them. And that’s normal to them; they expect that as a normal part of life that they have to learn how to navigate. That’s the other side of them being so engaged with these issues. As much as I’m optimistic, on the other hand, teens have to deal with [sexism] in a much more extreme, intense way than I did. It’s not that that culture didn’t exist back then, but people weren’t sharing nudes on Instagram. People didn’t have cell phones in school, or social media. It wasn’t such a pervasive part of our lives. We were still slut-shamed of course but it wasn’t happening in the magnified, intense way that it is now.

So you think it’s to survive that they’ve become so bold?

Right, and that’s sad. That’s a lot more depressing than thinking the next generation has it, but it’s also true. Our generation and the generation above us, we were so busy trying to get a foot in the door that we put up with a lot. “We’re so happy to be here!” It’s only now that we’re starting to realize being here isn’t enough.

In the book you mention a 2014 interview in which Lana Del Rey says feminism is uninteresting. I interviewed her a few months ago and asked her about that. As she tells it, it was a response blurted out after feeling somewhat antagonized by the guy interviewing her. It was her way of rejecting the expectation that she have an opinion about feminism at all. I wonder if others who find feminism unnecessary—and I don’t mean those who reject it because it doesn’t serve them, I mean those who dismiss it—also do so out of exasperation.

Feminism is still a dirty word for a lot of people. In some ways being able to say you’re a feminist is courageous, sure, but it’s also privileged. (If you’re Justin Trudeau, what do you have to lose from calling yourself a feminist?) Especially now that it’s cool again to be a feminist. But of course some people don’t want to say they’re a feminist, because they’re afraid of what other labels come with that. They’re afraid of being labeled something that they aren’t. On one hand, I think that’s fair. On the other hand, I worry about where that gets us. Neutrality can be dangerous when it comes to not speaking up. You’re also sending a message when you say you’re not a feminist, or when you refuse to engage with the politics. Who gets left behind when we’re too scared to engage? Or when we just don’t think it matters to us? I heard some good reasons from people regarding why they didn’t call themselves feminists, from people who felt the movement actively excludes them or is violent towards them—a lot of trans women and women of colour, sex workers. But the reasons for opting out are a lot different from the people who are just like, “yeah, it’s not for me.”

I think there’s a diligently achieved self-made state of denial at play sometimes, in the latter cases where privileged women denounce feminism because it just doesn’t matter to them.

That’s a very good way of putting it.

I also wonder if it comes from an attempt to get on the good side of the oppressor. In the case of someone like Faith Goldy, for example, and the well known online anti-feminists you write about in your book, money has a lot to do with it. But psychologically I have to wonder if there’s safety in being like, the world is so unsafe that I’m just going to ingratiate myself to the most dangerous kind of men, so that I become exempt from their harm.

It’s certainly individualistic. “I’m okay, so everyone else is okay.” I wonder sometimes if that’s their response to pressure. The practice of trying to do anything and everything can be exhausting. The system is against us in so many ways. Part of me thinks that the response is a survival mechanism, to get in, to get along and succeed and just pretend that the rest doesn’t exist.

There’s something pornographic about anti-feminism. It’s salacious and attractive to certain kinds of men. There’s a transaction of subordination exchanged between the two sides, just like in any performance.

Right, they’re each fulfilling the status quo goals of gender. When we look at people who are the most successful, they’re either not going against the grain or they’re going against the grain in ways that are attractive. Most people who are successful are playing out a very status quo goal of gender and what we expect, and yeah, for sure that becomes a transaction where they each expect and get success based on the ways we’re traditionally supposed to complement each other.

I thought of this a lot during the Jian Ghomeshi trial. There was a conversation around how nuanced and complicated and difficult it seemed for a strong female lawyer, Marie Henein, to represent a man accused of sexual assault. But wasn’t she doing exactly what would be expected of the law? She didn’t do anything during that case that fascinated or surprised me. She used the same tactics that are always used to discredit accusers. Ultimately it was status quo.

It wasn’t necessarily her that was the problem. Like you said, it’s the system, and that we were expecting justice for survivors in the court system at all. There are so many layers to it, but they all got pinned on her because she was the one out there performing the role. We expect everything and nothing from women.

In the book, you reference something Canadian men’s rights activist Karen Straughan said to you, which is that feminism is designed to make men feel awful. I latched onto this, because in some ways feminism makes me feel awful. A peer of mine recently tweeted a joke about sexual assault. I’ve crafted three different emails to this guy to try and talk to him about it, but I keep relenting. I don’t want to embarrass him. I don’t want him to turn on me. I don’t want to be seen as a problem. The burden goes the other way, too. (My earlier comments about not cowering are waning here, I realize.)

Absolutely. I’ve heard so many of my friends say, “I’m the feminist in the office,” “I’m the one who always speaks up,” and that’s a huge burden. There’s social pressure on women to be likable. That’s how we make it in the world. And when you’re speaking out, you’re not likable. You are instantly not likable when you speak out. Or you have to try and think about saying it in the right way to maintain likability but still get your point across. It’s exhausting. In a world where it is still unpopular to live your feminist politics, of course there’s a burden on you for speaking out, because you never know what the answer is going to be. But it’s okay to be scared, as a feminist. It’s okay to be worried about getting yelled at, or having a Twitter hoard come after you, or being doxxed, or belittled in front of your office or to have someone call you a bitch. We put this onus on ourselves to be so tough. But it can be exhausting and frustrating and heartbreaking sometimes to be a feminist.

We tell women and girls they can be anything they want, but when you try to be that thing there are so many different constraints—you can’t be emotional, and you can’t be too ambitious, and you can’t be too loud, can’t be too angry, you can’t speak out too much. You can be anything you want, as long as you’re not trying to force your way into a male-dominated industry. This idea that you can be anything really comes with a lot of contradictory footnotes.

On that level I understand why some women reject the burden. Actually a lot of men’s rights activism and anti-feminist activity happens inside the home, alone. There are conferences and rallies, but so much happens from behind a computer. They’re already opting out physically.

Well, they’re living in the world of soapboxes and angry Twitter hordes too, right? A lot of the women I interviewed showed me the online threats they get. It’s not like they aren’t saying horrible things, but when the conversation descends into death threats, where are we really getting? As much as I talked to the stars of these movements, the public figures, what we have to be worried about is how those ideas are connecting on a mainstream level and how they’re playing out with who we vote into office, our attitudes at work, our attitudes at home, our day-to-day attitudes. It’s so easy to be outraged by a video we see on YouTube or a tweet that is meant to provoke us, but I think we need to ask how this rhetoric is being normalized and what it means for turning the tide of conversation. These things have been around and never went away, we just pretended they did.

You note that many MRAs make a point of saying that that they don’t hate women.

I think it’s a way of making their ideas more palatable to a mainstream audience. People don’t want to say “I hate women.” Well, most people do not want to say that. That’s not a contemporary thing to say. But to say, “Oh, I’m concerned about where women’s roles are going,” and, “We need to value mothers,” that’s something people still feel justified in saying. That’s something you can build an argument on. In the same way that people can say “I think we need to be concerned about immigration,” it’s all very coded language. It’s language that’s acceptable. It’s language that can spread.

Have you kept up with the conversation around Lido Pimienta winning the Polaris Music Prize?

I have, and I think it just plays back into this idea that we don’t like women who advocate for themselves. We still expect women to behave a certain way. The idea of a strong woman still happens in certain confines of how we expect women to be. “Well, we elevated you, and you’re a woman, shouldn’t we pat our backs for that, and shouldn’t you pat our backs too?” That’s not where we need to be. Stuff like that makes me so cynical. We want to be congratulated for doing the right thing for women, but we don’t actually want to hear what women have to say. We want to put them up on a pedestal but we don’t actually want them to be human.

A large media company hired me to write, in their words, “feminist hot takes” a few years ago. When I got there they had me editing more than writing, and as soon as I started taking misogynistic sentences out of articles and declined to hire an accused serial rapist, my day-to-day work life was made impossible by men who didn’t want me there anymore. They’d hired me to churn out cool feminist click-bait. When I tried to implement not just feminist politics, but basic safety for others in the actual workplace, they were like, “no, get out.”

People like to watch feminism as a spectacle, because then they can tear it down or ridicule it. When it comes to living it and implementing it as politics, it’s so much harder. It forces people to confront things in a way they’re still not prepared to do. People don’t want to hear you be thoughtful, they want to hear you be angry, because then they can say “look how ridiculous you are.”

You write that, “In all the great women-on-women wars, none has more controversy than Stay-At-Home Mom versus Working Mom.” As you say, this strife really picked up when, in 1975, Simone de Beauvoir told Betty Friedan that no woman should be permitted to stay home and raise kids. How much of a role do men actually have in shaping the ideologies of anti-feminism? Is this movement more about women themselves than men?

I think it depends on what level of the continuum you’re on. I certainly don’t think by any means that these women are like puppets to the men in their lives. Even though one might not agree with their politics, they fall into the stereotype of the strong woman. They have their own thoughts. They do their own research and they form their own opinions. Often the men in their lives are not as radical as they are. It’s not even that they hate women, I think what they’d say is that they hate the feminist ideology, because it presents women as perpetual victims and it tells women that they can have it all, when really we were better off in traditional gender roles. Even though a lot of them are men’s rights activists, it’s almost as if men don’t factor in at all.

In another sense, men factor in because as feminism succeeds, traditional roles for everyone will break down. So they look at the traditional roles of men and see that those are not as entrenched as they once were, and they blame feminists. There’s this idea that if men’s traditional roles are under threat, women’s traditional roles are under threat, and if no one has their traditional roles then where are we? Chaos reigns. When it comes to that, it’s not only about wanting men to maintain traditional roles and their place in the world, it’s also about women maintaining their roles and their place in the world. There’s comfort in that for women who find themselves lost or just as baffled by the changing world as some men do.