A key scene in Mia Hansen-Løve’s new film Eden hinges on an argument about, of all things, Showgirls—Paul Verhoeven’s much-maligned striptease fiasco, and, in the estimation of me and many others, an unheralded masterpiece. Someone in Eden actually agrees: “It’s not crap,” the obstinate Arnaud insists after screening the picture for his friends a third time. “It’s the masterpiece of the ’90s.” This debate is typical of the pleasures of Hansen-Løve’s heady, free-floating film. People bump around and drink and smoke and wax philosophically, taking in vast swaths of popular culture and becoming self-styled experts in trivial fields. The fun is infectious. Scarcely has a movie made it seem so appealing to simply hang out.

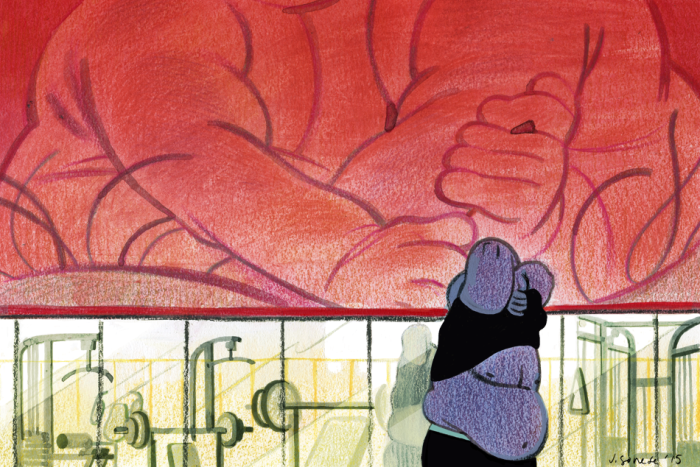

The subject is the “French touch”—a movement in underground electronic music that helped launch bands like Daft Punk to superstardom in the late ’90s. The hero of the film is Paul, very closely based on Hansen-Løve's brother Sven—a real-life DJ and fixture of the “French touch” scene who worked closely with his sister on the movie. Paul, like Sven, never grasps success to the Daft Punk degree, and part the tragedy of the movie is how just how long he spends trying to find it. You can only stay out all night DJing so long without a lifestyle taking the place of a life. Eden spans twenty years and digs deep in a very specific subculture, but its enthusiasm, and its insights, are broader than any one niche. It’s a film of universal affection. I caught up with Hansen-Løve after Eden’s premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival last September to talk about music, aging, and the specter of 9/11. But of course we started with Showgirls.

*

Calum Marsh: Tell me about Showgirls.

Mia Hansen-Løve: I haven’t seen the film for many years, to be honest, so I don’t have any idea how I would feel today if I watched it again. I should. But the idea came from the fact that my brother and I have a very close friend, who is one of the inspirations for the film, who has been literally obsessed with this film for years. There are actually two films he’s been obsessed with: one was Showgirls, and the other one was Heaven’s Gate. When I was 15 or 16, I did spend a lot of time at his place. He was actually trying to go out with me! But he did that with many girls—it was the one way he tried to seduce girls, showing them Showgirls, again and again. It never worked. I don’t know if it’s really the most convincing way! Anyway, this obsession he had with this film—we had a lot of sympathy for that, but I do think that film represents something symbolically; it incarnates the ’90s in some ways. I’m not saying that because the world of Showgirls would have anything to do with the world of my film—it hasn’t.

It’s more representative of American culture?

Yes, I’m saying that in the sense that it tells about the relationship these people have to American culture. That’s the one thing that interested me. I could not have imagined this scene being in a French film, for example. This guy who inspired us in this scene, but not only him, his world, his friends, they are really people who have a very strong—maybe too strong, in a way—relationship to the American culture. In some way Showgirls is really the condensation of that. That’s why I thought it was interesting to pick this film in particular: because it truly reflects that, and that’s something you can also see in the music. They are the people who introduced American house music, and garage music, to France. They are people who are very open and into American underground culture, and their relationship to films is part of that. I think even with Daft Punk it’s true. The interesting thing is that we talk about “French touch”—the film is about “French touch,” but actually “French touch” is about these French people who have a connection with American culture, in a way, [but] they are very French at the same time. It’s in the middle; it’s both, you know? I think the Showgirls scene is connected to this question of trying to define my generation, and their feelings, and their relationship to the world at this point.

I think in America Daft Punk is associated quite strongly with French culture, not American culture. They’re thought of as almost quintessentially French.

Well, Daft Punk is very French in many ways, but Daft Punk is very different than most of the music in the film. Garage music is really something that is deeply rooted in the underground American culture. That was one of the difficulties my brother had to face with this music; it was very cool at some point, and it had a huge success with these parties, but still, compared to other branches of the music, the garage music always remained something a little bit too specific for the French audience.

So it was considered somehow exotic?

Yes, and also the fact that it was very lyrical, with the garage, the disco thing. That’s the one thing that’s particular about it; that’s the one thing I love, but that also was the limit for some people. The more commercial electronic music—that you hear when you walk in the streets of Toronto—it’s not this music; it’s techno. The garage music my brother used to play always stayed something more underground, marginal, something of an outsider.

I find it interesting that the character’s taste always seems frustratingly off-trend. If he’d been making, say, dubstep or something, he’d have maybe broken into the mainstream in the mid-2000s when that became popular.

In this film you have the very crucial scene in the second part of the movie, when the boss of the club, who is actually played by a guy who inspired one of the characters of the film … He’s not a boss at all, I mean, he’s one of them, and it was fun to make him play the other side—you know, the one who doesn’t have hair, Vincent Macaigne? So the guy who plays the boss is actually the real Vincent Macaigne … Anyway, in this scene, for the first time you have somebody criticizing the music, and telling them maybe they should try something else, and that maybe it’s not as popular as it was. And that’s the scene where it actually talks about David Guetta. The one thing I liked about this, at the end, is that he tells them, “you know this club, the lesbian club? It’s a huge success. They play electro—don’t you like electro?” And a lot of the people in the audience must think, “but that’s what we’re listening to!” Suddenly you realize how wide this world is, because maybe Sven’s music is never considered to be electro. What we call electro in France is something different. I like the fact that it should be disturbing for the audience that somebody tells them, “Why don’t you play electro?” and they’re like, “Come on, that’s what we’ve been listening to for two hours!”

Yes, I know, and the idea that someone could hate one and love the other seems absurd. But I’ve talked to people that are really into that music scene, and if you heard something and said, “Oh, this is techno,” they’ll go, “this isn’t techno at all!”

My brother is always scared, because when the film is released in France, there will be some parties, and programmers want to do their own programming, and my brother always says, “I hope it’s not gonna be techno.”

I think one of the effects of the film is that it compels you to rush out and listen to this music. The people I saw it with wanted to head out and dance.

It really makes me happy to hear that, because I’ve never made a film with the purpose of trying to make people want to dance, and it’s the first time. There was nothing I wished more than to really make people love this music. I know a lot of people don’t, and won’t, and will get bored in the film because if you really hate the music, you don’t get the scene, and you don’t get what it’s about. But I know there will be some people who do like the music, and will be affected by it, and to give us a chance to have that music at the centre of attention in a film, that’s very gratifying for us.

How was the soundtrack compiled and curated? Was your brother involved in that aspect?

We worked so much on it together. We worked for about three years on the film, basically, and the first year, in terms of the music, was really about getting back to all the music we were listening to at the time. Sven and I had more or less stopped listening to this music, these songs that are really specific to these years—the songs you used to play in 1992, or ’96, or ’97. The first level of our work was to rediscover all this music, and it was very moving for us. It’s just like smells; when you listen to music that you haven’t listened to for, like, ten years, it brings back so many memories. There were songs that were attached to some specific clubs, some specific times in our lives, and some specific memories. It was something we really did together, sitting next to each other at our computer, listening back to this music, and choosing and seeing the relationship this could have to the scenes, and how we could make sense of it to have this specific song, in this specific club, in this specific scene. In the end, because we spent so much time on it, I really feel like they all have a very precise meaning. Most of the time, even the lyrics are connected to what’s happening in the scene.

Was there a sense of wanting to be comprehensive about this genre, to show people the full extent of it, or to have a definitive playlist of that sort of music?

Not really. Well, of garage music, in a way, yes, but not of the “French touch.” I think, about the film, we have to be honest, and we have to distinguish two things. On the one hand you have the garage music—that’s the music that this DJ chose, and tries to defend, and tries to transmit, and on this level we tried to be almost pedagogic; we tried to make a very precise ... what do you say, a summa of what it was, also in terms of chronology. But we didn’t do the same with the “French touch”—when we talk about “French touch,” we talk about French musicians who did their own music, and that’s what we didn’t really show, apart from Daft Punk. In the film you only hear—I mean, talking of French musicians, of DJs who became what we call the “French touch,” we only see the work of Daft Punk and Cheers, but there are many more than that. I’m sure people will say that, by the way: “Oh, but they didn’t show that, etc.” But that was a choice, because we couldn’t show everything, so we preferred to be very good in our own, specific area, and be precise there, and make very clear choices, instead of trying to show a little bit of everything.

How important was the sense of authenticity in the film?

It was very important for me, and for my brother—it was, like, his obsession. For me it was very important, of course, but sometimes I would say, “C’mon, we can’t please everybody anyway, we just have to focus.” But Sven, and I think he was right to be stubborn, because it’s his entire life, for him, it was so crucial that everything had to be true, authentic—the music, of course, but also the sets: we paid a lot of attention to the different clubs, and we tried to film at the right places, places where it actually happened. It was also very important for us to have the real people playing their own parts. The DJs and singers you see in the film, it’s them: it’s them my brother used to go to, and it’s them who used to sing at these parties. It’s them, fifteen years later than the real story, but they hadn’t actually changed that much. It was crucial for us, symbolically, to have these people involved in the film. The other thing that was very important was to have that scene in Chicago, because for us it was the moment where we go to the very source, of where everything started. When we did the first editing of the film, and people saw it, some told us, “It’s too complicated in Paris, New York, and then Chicago. Why did it have to go to Chicago? Why don’t you keep the scene but put it in New York?” But for us, it was very important. We couldn’t imagine to have moved the scene from Chicago to New York. My brother always talked—when I was 15, when he started listening to garage music—it was always all about Chicago, and you would go to these guys, to these DJ producers, and you would go to them in Chicago just for one day, to listen to just one track, and that was something we needed to have in the film, if we made a film about garage music.

Was it actually Daft Punk as themselves at the end of the film?

No, they would never do that.

I assumed so, but there’s a rumor going around that it’s them.

I would love for people to believe that, and I think they, the real ones, would love people to believe that, because it’s part of their disguising themselves. It’s part of their play, their identity, and I truly think they would love people to believe it’s them, but they would never do that. I mean, they’ve spent their life hiding themselves. Even if they like us, it’s okay, but they would never show their faces in a film, ever.

That’s why it’s funny—the joke is that they’re never recognized.

I even read in some paper that it was them acting in the film, in all the scenes, and I was like, “How can you believe that?!” It’s interesting—it shows how powerful their aura is, that as soon as you put their names, it’s like, “It’s them!”

I do like the idea that the movie reduces these mythic figures to normality. They’re just regular guys who can’t get into a nightclub.

We weren’t interested at all in showing them in the robot thing. It’s much more interesting—even with all the mystery and the fascination, and we believe in this mystery they have—we felt that showing them as they are, young boys who become young men, just like everybody else, real people, actually made the mystery about their success and the grace of their music even stronger.

I thought so too. Is the club that they’re at together, at the end, the David Lynch-owned club in Paris?

Yes it is, Silencio. And the guy, you know, the guy who tells them they are not allowed to get in, at the end, is the guy who actually did that to them. He played his own part. He said it with the words that he actually said to them. It was really nice for me that he actually accepted his own part, because it’s something that people make fun of him, for not having recognized them. It’s so weird, this guy doesn’t even care—he has a self-humour, and he thought it was funny to play it.

It must have been fun to compile all these real-life moments together into a film like that, because the film, obviously, for someone who’s not familiar with the real experiences, it’s simply a fiction film. But it has that aura of authenticity all the time; it feels so real.

I hope so. That was something that was always reproached to me when I was trying to finance it. People would say it’s too specific. It’s not universal enough. But I always had the belief with my films, and even more with this one, and Sven shared this belief, that to be profound, and authentic, in the kind of film we want to do, we had to be very precise and specific; we shouldn’t try to build stereotypes, and make conventional scripts, just as people are asking of us all of the time.

The basic narrative framework of the film resembles a lot of rise-and-fall stories. Were you consciously following those conventions?

It felt more that life itself was following some conventions. We were aware that there was an aspect of the film that was rise and fall, and we didn’t mind, but it’s not like it was something we tried to overdramatize, or to put in the front. It was just while we trying to have fidelity to life, we realized that being close to life, and in what really happened in my brother’s life, we were finding some universal schema, rise and fall—but that’s actually my brother’s life. We didn’t mind, but we didn’t try to construct it this way. It just imposed itself like that. Actually, in the first draft of the film, it was two films. It was the same way, a garage paradise with lots of music, but it was two feature films. That’s my big regret about this film: not being able to finance it, because there were people who were following me, or us, on this level, when this film was at this scale, but not enough people. That’s why it was so difficult. All the time we had to make it shorter, and shorter, and shorter, until it became financeable, but I still think that the most beautiful version of the film had been this two-film version.

Was the overall structure still the same for both parts?

It was absolutely the same, there were just more characters. In a way it was even more radical, I would say, because there were even more characters; it was even more creative. I’m not saying that the film is crazy, but people would say, “Oh, there are too many characters, there’s not enough dramatization,” so I would say that because it wasn’t longer it was even less dramatized, even more impressionist, and it was even more about being really immersed in a world. I think people would have hated the four-hour version, but it would have been my favourite one. It would really have been an epic, you know, about the ’90s, and the people involved in house music in the ’90s. We tried to save the ambition of the film as much as we could, but we had to cut so many scenes before we were finished with it.

Well there’s always the DVD release—you could do a full cut.

Aaaah, I wish, but I don’t have the money!

Tell me about the decision to age the character in the way that you do—or rather, not do. We follow Paul for twenty years and he looks virtually the same in the last scene as he did in the first.

Well, my brother is 41 soon, and he looks so young. Everybody thinks he’s younger than me; he’s seven and a half years older than me! Something that helped me with the fact that I couldn’t make him age so much was that my brother stayed young. I mean, it took him such a long time to start to look more than 25 years old! It’s crazy. He was already 35, 36, and people were still thinking he was 23. I think it has to do with his way of life, actually, like some kind of immaturity. But that gave me confidence when I was not trying to make Felix much older. But at the same time, we did expend quite a lot of energy trying to figure out, in the schedule of shooting, how it could allow us to have moments when he’s shaved, moments where he has a beard, when he gains weight. There are actually moments when you do see him change, but it’s true that the moments are very light and subtle, because I’m generally not convinced by the very heavy ways of making actors look much older. I just think it doesn’t work. For me, it makes me feel more like I’m in a film. The only way to really do it properly would be to do it like Richard Linklater has done. [But] I didn’t want to do this film over 20 years, so if you can’t do it this way, I would rather do it in a very simple and minimalist way.

The other characters are aging around him, though.

Yes, and the one character, actually, who carries the responsibility for getting older more, is the girl. She changes much more than him. That’s also because she’s moving on, you know? He stays stuck in his way of living and existing, and she moves on, and I liked to have this contrast between her, changing clothes and hair, and having children, and he’s still the same.

What was your approach to structuring the film? It seems difficult for a two-hour feature to accommodate a twenty-year story.

I did it the way I did it for Goodbye First Love (2011), actually: in a very intuitive way. I followed my inspiration. I didn’t try to be democratic, or to give every specific year an important moment. There were some years, like when the second part starts, you see the years coming more quickly, but that was also about the fact that when you grow up, the time goes faster and faster. So there was this idea of the acceleration of time in the second part, which is actually much shorter than the first part, but in the first part you have ellipses, and it’s pretty much balanced. But I didn’t try to be democratic. I didn’t try to show everything, or to be fair to everybody involved in the music scene, I just trusted myself in choosing moments that I wanted to capture that were important for me, even if they weren’t the more dramatic moments, or the more defining moments in terms of the music. But those were the moments that I wanted to film; I’ve always had this belief that one thing that’s important when you make a film is that you want to film the scene. It’s not that you should film the scene, it’s the desire you have to film the scene, the dialogue, and the atmosphere, and I always trust this desire of filming this and that. I’m not afraid of the idea of leaving some stuff aside.

And you resist the urge to keep tabs on the secondary characters.

Yes, and in fact there are characters who disappear in the second part, and we never see them again.

How close would you say the film is to your brother’s experiences?

Well, yesterday someone asked that to him at the Q&A, and he said 100 percent! I wouldn’t say that, because for me it’s still fiction, in the end. I agree more with him when he says, as he also said yesterday, that him and Felix, the actor, had this joke, that when they were alone, they always had this feeling when they were doing this film that they were a third character called Paul. You know, there is Felix, the actor, Sven, and Paul. For me it’s more like that—I don’t feel like Paul is my brother, because Sven’s implication in the writing was totally crucial, but in terms of the characters, the structure, the scenes, I had written more of it, so it’s my own interpretation of his life. I’m sure if he had really written the script, entirely on his own, the result would have been totally different. So I don’t see how it could be 100 percent him, because it’s my perception as a younger sister, who wasn’t there all the time, you know? But it’s true that much of it is close to both the events of his life and to his more intimate feelings.

The presence of 9/11 seems to loom over the end of the film’s first half, but you rather conspicuously avoid mentioning it. Was this deliberate?

Yes. I had it in mind, totally, but in the film the characters are in New York just before it happens. It was mentioned in the longer version—it was mentioned and there were things about that, but it’s not accidental at all. The other dates in the film appear small, but when it’s 2001 it’s bigger, because for me it’s the last big moment before the end. For me, even if it’s left off screen, the ending of paradise garage is September 11th, definitely. It’s totally not accidental that we put it in 2001. There are two reasons for that: one is the release of “One More Time,” which is, for us, the peak, the pinnacle of the success or the climax of this world; and it’s the beginning of the end. You have “One More Time,” and then you have September 11th, and then that’s over, in a way. And I mean, it’s not because it’s something we used dramatically, because I didn’t use it dramatically, but in our life, that was the case. I remember the day that it happened. For me, it’s connected to a moment when we stopped being innocent, in a way, in our relationship to the world. There was some kind of different melancholia after that. There was some trust in life, you know, trust in our time, trust in our progress, in a way, because I do think through the ’90s until then, there was some kind of trust in our generation. There was the idea that we were in good times. I mean, there were tons of horrible things, but there was some kind of trust in the future, and I think that was literally stopped by September 11th.

Does it make the music seem more frivolous by comparison, because now there’s this enormous real-world event that contrasts with it?

Well, I don’t know if it makes the music more frivolous, but it makes the ideals, the utopia more unrealistic, more of amirage. Something that’s there but then suddenly it seems like it disappears in the air. It’s an illusion. You can’t grasp it anymore. It’s like it’s vanished.

It seemed to me like a structuring absence: you can feel its weight even though it isn’t discussed.

The guy who kills himself, in the film, was inspired by a friend of ours who was a great drawer, and it’s his drawings we see. Most of the drawings you see en scene are his drawings. He also made this comic with our other friend—the comic really exists, and it’s a great book—he’s made great, great drawings of that. But I couldn’t use it, because after his death we didn’t go back to him and see his final drawings. There was no space in the film for that, but we actually had very beautiful and striking drawings that he had made about the towers and the planes.

Would you characterize the film as a kind of cautionary tale?

No, I wouldn’t. I think people can see it this way, and I wouldn’t mind. I mean, parents … sure. But I don’t see it this way, because I think the film actually doesn’t say, “you should not do drugs,” or “you should not drink,” because I think the scenes where the characters in the film are the most happy are mostly connected not only with the music but with the absorption of drugs. So it doesn’t say, “You should do that, and it’s great,” but I never judge. Something very specific in my films is that they are not moralistic. They really are not. And they don’t pretend to be subversive, either; they don’t say, “Ah, wow, we should do that, and we’re taking drugs!” It’s not like Larry Klein, you know. It’s far from that. But I think it’s also far from trying to warn people, “Don’t do that, because after you won’t get a job, you’ll be lost, and you’ll see people around you having children and you will feel like a failure, so you should be careful and not go to parties.” No: that’s very far away from me. I’m 100 percent in empathy with them having fun, and I just think it’s essential and beautiful.