Virginia Hamilton Adair went blind when she was in her 80s, and then she started seeing things. In Oliver Sacks’ new book, Hallucinations, he quotes from one of her journal entries, dictated to an assistant:

[T]he sea of clouds at my feet clears, revealing a field of grain, and standing about it a small flock of fowl, not two alike, in somber plumage: a miniature peacock, very slender, with its little crest and unfurled tail feathers, some plumper specimens, and a shore bird on long stems....The birds have turned into little men and women in medieval attire, all strolling away from me. I see only their backs, short tunics, tights or leggings, shawls or kerchiefs....Opening my eyes on the smoke screen of my room I am treated to stabs of sapphire, bags of rubies scattering across the night, a legless vaquero in a checked shirt stuck on the back of a small steer, bucking, the orange velvet head of a bear decapitated, poor thing, by the guard of the Yellowstone Hotel garbage pit.

Adair’s form of hallucination is called Charles Bonnet Syndrome, or CBS, and it’s unlike the kind of hallucinations that come with schizophrenia—for one thing, people with CBS know they’re hallucinating. Sacks describes the experiences of another man with CBS who still had his ordinary eyesight: “he was being driven in a car and began to see, on the edges of the parkway, elaborate eighteenth-century gardens which reminded him of Versailles. He enjoyed the experience and found it much more interesting than the ordinary view of the roadside.” As with Adair’s sapphires and rubies, this spectacle is like visual embroidery. Not all CBS hallucinations are this pleasant; Sacks quotes a woman named Zelda who had a strange encounter with her mail carrier: “‘As I looked at her, her nose grew until it was a grotesque figure on her face. After a few minutes, as we stood talking, her face came back to normal.’” But it does seem as if one frequent function of CBS hallucinations is to increase the world’s beauty.

Adair’s CBS came on after the publication of her acclaimed first book of poetry, Ants on the Melon. Before she died in 2004, she went on to publish two more books, which include some poems dealing directly with her blindness and hallucinatory experiences. In “You and You,” she writes: “New forms and faces make their mark/ in my impenetrable dark./ What in a disembodied ghost can make me love some more than most?” Another poem, “Thresholds,” begins: “I stand at evening in the open door,/ and see the wind I never saw before.// Freed from the restless eyes I’ve left behind,/ I move through endless galleries of the mind.”

It’s Adair’s early poems, however, the ones written before she contracted CBS, that read more like visions to me. Here’s an excerpt from her poem “Surfers”:

Four half-grown figures start

down the precipitous headland

hung with crimson ice plant.

Ceremonial as a crucifer,

each with his surfboard raptly faces

the blue-mauve insomnia of the sea.

They place their boards like prayer rugs

kneeling with reverent grace

to the messianic wave

forever watched for

forever coming.

Reading this, I’m struck by how surreal surfers are; it’s weird that half-grown men thrash around in the ocean on planks of polystyrene. Part of the job of poetry is to give real things the quality of hallucinations—to make them feel startling. In a way, poetry’s premise is that the reader can accept a reality heightened by unreality. At a poem’s opening, the reader doesn’t yet know which elements are to be taken literally and which figuratively, and as the poem advances, disparate elements—imagery, ideas, narrative, metaphor—are brought together into one complex entity, like a visual field containing both a real armchair and a hallucinated flock of peacocks and shore birds milling around in front of it. In readers, it’s a virtue to see both.

Reading accounts from people with CBS in Sacks’ book, I felt almost jealous. In high school I used to sit in particularly boring classes and imagine something—anything—happening in the room. I would look at a textbook on someone’s desk and picture it rising up and hovering in the air. I had whole lists of animals the people in my class would be if they turned into animals (Tammy Baker was a squirrel), and objects they would be if they turned into objects (David Sullivan was a jar of peanut butter). CBS hallucinations seem to make the world a more mutable, less constrained place, which would come in handy for a poet.

But, as Sacks points out, part of the difference between hallucinating and dreaming or imagining is that hallucinations don’t feel meaningful. One of the first lengthy descriptions of CBS was published in a psychology journal in 1902, around the same time as Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams. Sacks writes: “some wondered whether the hallucinations of CBS might afford, as Freud felt dreams did, ‘a royal road’ to the unconscious. But attempts at ‘interpreting’ CBS hallucinations in this sense bore no fruit...The theater is in one’s own mind, and yet the hallucinations seem to have little to do with one in any deeply personal sense.”

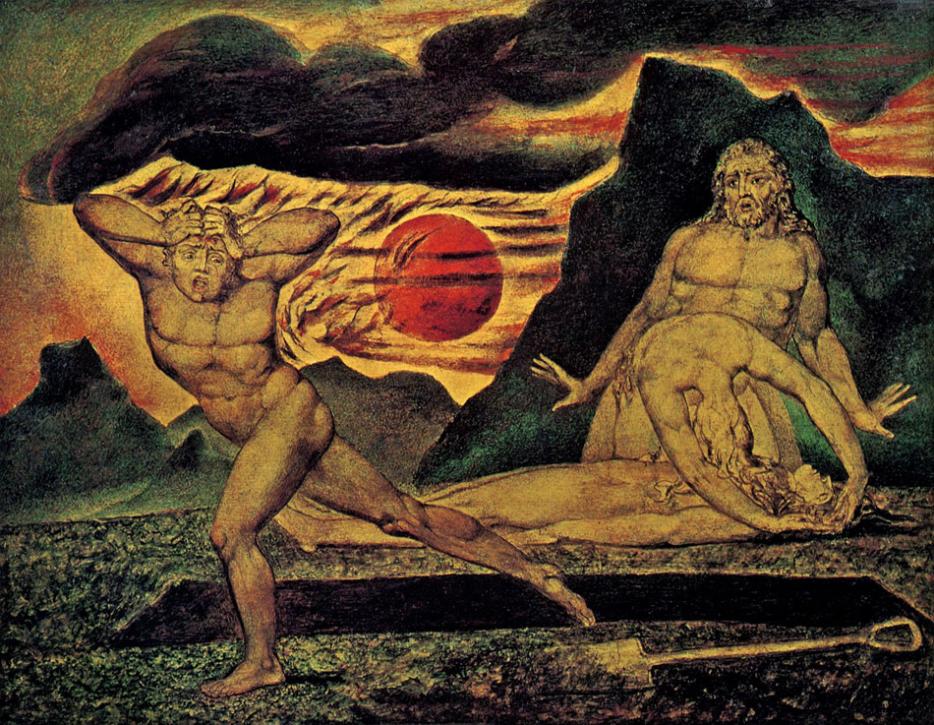

The poems in Adair’s Ants on a Melon are often intensely visual, and her later work less so. I’m sure this is partly because she had gone blind, but I wonder if it may also be that her unbidden, arbitrary visions changed her attitude about visual imagery—seeing a constant parade of peacocks, tiny people, and headless bears might make the look of things less meaningful. In her later books, she devotes more and more thought to religious themes. Maybe when you start to see things you can’t believe in, it makes it easier to believe in things you can’t see.