What was important to us in 2014? Hazlitt’s writers reflect on the big issues that reverberated quietly and the small moments that rang loudly over the last year.

My parents didn’t let me date while I lived in their house. They are Indian and conservative and very concerned about how girls should “behave” in public—here’s the sound of my every feminist fiber shrieking—so I wasn’t even allowed to have male friends, let alone hold hands with one. Not that anyone was breaking down my door to take me to East Side Mario’s—it was just the principle of the matter.

And that’s not to say I didn’t try—it was just always more trouble than it was worth. My first boyfriend dumped me because I couldn’t risk being seen with him at the mall. My second came from a similarly strict household, so we would run off into the wooded areas of southwestern Calgary to listen to Elliott Smith and smoke Player’s twice a week.

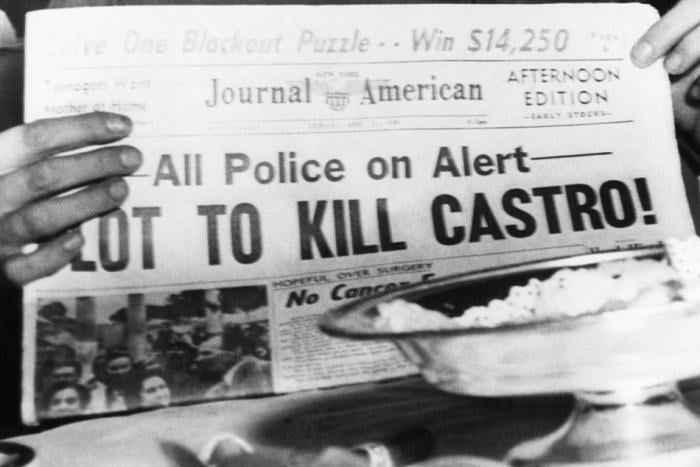

When I moved away at 17, I started lying to them about every detail of my life. If you asked them, I was always home at a reasonable hour, passing all my classes, and very, very respectful of the elderly. It was easy, usually, since so much of my life was disposable and unimportant. But three years ago, I fell in love with an idiot man, and lying to my parents became more and more childish and selfish. He brought me home for Christmas and Easter and Thanksgiving and told everyone he knew about me. In 2011, he took me to Cuba for my birthday. At the resort, I rallied four strange women to let me give them fake names and take pictures with me—to pretend they were my friends so that my parents wouldn’t know that I went with a man, alone.

With our third anniversary looming earlier this year, he pressed me to be an adult and tell my parents about this big part of my love life that I’d worked so hard to stop from bleeding into my family life. He was right. I was keeping him hidden, and it was unfair.

I suspect that in every relationship, there’s a moment where you look at this person you’ve chosen and say one of two things to yourself. The first is either a statement of regret or indifference, both equally horrible things to feel about someone with whom you’ve been building some sort of life. The second is some variation of, “I would punch myself in the teeth right now if it made you feel marginally better.” This one is arguably worse because it forces you to put aside your comfortable selfishness and legitimize the needs of another person. Lying to myself—and my family—was really easy, really convenient, and really good about giving absolutely nothing to the other person involved in my lie.

I also knew the situation was more complicated than my doofus boyfriend—with his divorced parents and small-town Ontario upbringing—could comprehend. He is the whitest person I know and older than the sun, two things I was sure would make the whole scenario worse for my parents, who are brown and a mere four years apart themselves. At the beginning of 2014, I decided I’d bring him home at the end of the summer, and spent months feeling increasingly angry about my parents’ unwillingness to be flexible.

When I was younger, I’d fantasize about what it would take to get my parents onboard with me having a love life. I would imagine a Die Hard situation where some boy and I would get trapped in my junior high school by some white (very important to my family that they be white) terrorists with big guns. The boy (Grant or John or Other Grant or Alex or literally any boy who had ever knocked me over in gym class on purpose) wouldn’t exactly rescue me; rather, we would save each other, save the school, perhaps save the city from the bomb the terrorists had planted in the basement of Calgary’s Chinook Centre, our most prestigious mall/movie theatre/bowling alley. The boy, who previously thought I was quite lame, would realize that I’m great (and very attractive) and we would fall in love. After foiling the plot, we would emerge from the school’s air ducts, dusty and inseparable. My father, suddenly sage-like and not playing the walking Charizard that is his usual resting state, would give us his blessing.

This is literally the only way I could have ever gotten my parents to approve of me dating someone they hadn’t personally selected. I spent half the year worrying about being disowned. When I said as much to my current boyfriend, he maintained that it was time to be an adult and do the adult thing. “You have to stand up to them,” he said after I got off the phone with my parents, removing from his mouth the sock I used to keep him quiet so they wouldn’t hear that I was with a man.

With our first trip as a couple to my hometown planned, I thought about what would happen if I got into a horrific car accident that would leave me mangled (though in conveniently tragic fashion, basically meaning a few broken bones and no long-term damage) and how he’d help me learn to walk again. Or, hey, I could always slip into a coma for a few days and then wake up at the sound of my beloved’s voice. When I went to Paris on my own two years ago, I imagined being kidnapped (in Paris? Come on), forcing my boyfriend to come rescue me. It would be like Taken but worse because I am very annoying and my captors would murder me almost immediately. Just like I imagined as a seventh-grader, something cataclysmic needed to happen to me for my boyfriend to gain my parents’ trust and sympathy—something where my life hung in the balance, with him nursing me back from the brink. That would make them love him like I do. Then, last year, my boyfriend shattered his foot and wrist in an accident. I was upset that he was hurting, of course, but also that the universe misunderstood my vague prayers. It was supposed to be me, you fools, I hollered at the sky while wheeling my boyfriend and his many casts around Greektown.

“You have to stand up to them,” he said after I got off the phone with my parents, removing from his mouth the sock I used to keep him quiet so they wouldn’t hear that I was with a man.

I told my parents about my boyfriend, that he existed, and that he would be visiting with me this past August. They really did not want to meet him. My mother told me she would “write it in [her] own blood” that she would never speak to me again when she found out how old he was. My dad tiptoed around calling me a harlot before accusing me of “giving” him chest pains. They refused to host us in their home, then flew into a rage when my brother shrugged and said we could stay with him. My dad didn’t talk to me for three months. But then, a week before our flight to Calgary, my mom relented and agreed to let us enter the house in which I grew up. My long-suffering boyfriend packed a bag to fly across the country and asked me, so sweetly, so preciously, the little idiot baby angel he is, if we would be allowed to sleep in the same bed.

When I walked my boyfriend into the foyer of my parent’s home, I waited for weeping or screaming or violence or, at least, my father offering a performatively cold shoulder. But they shook hands. My four-year-old niece was running around, talking about how her “new uncle” got her a Blue Jays hat from Toronto. My mom made everyone tea. My dad told him he looked “good for someone in his mid-30s.” It was… fine.

It was not all fine, of course, because the world is a place where destruction festers—little things bubbled up and started to bother them throughout week. My father eventually threatened to never speak to me (again) when I told him we were planning on moving in together, barking at me when my hand lingered on my boyfriend’s shoulder too long, culminating in him saying that my arms were becoming “unmanageable” in their size (unrelated, I think, but very important to him). One morning, while my boyfriend showered, my father told me that he roamed the top floor of the house to “make sure everyone was in their own beds, as they should be,” which tapped into my greatest fear of having my father recognize that I have a vagina and my boyfriend has a penis and that sometimes they enter the same airspace.

And yet, this still exceeded my every expectation—my father never even set his will on fire while screaming “YOU’RE DEAD TO ME” like the village soothsayer always warned me about.

Later this week, I’m flying back to Calgary to see my family for the first time since I introduced them to my biggest lie in person. My mom is trying: she asks about my boyfriend and suggests that we get married within the year so that my dad can get some peace. (We are not doing this.) Before we left last summer, I caught my dad saying that he was “troubled” by how much he likes my boyfriend, but has since resumed his status quo of pretending he doesn’t exist. Most of my year was spent waiting for the sky to fall, but instead, it’s just been eerily quiet. They haven’t threatened me, they haven’t bolted from my life—really, they haven’t said much of anything at all.

It’s only a matter of time until I find the next thing sets them off, though. Four years ago, my dad stopped talking to me for 10 days because he thought that the $30 laptop case I bought for myself was too expensive. Who knows what’s next? Fury over the fact that I am old enough to watch movies with bare-chested men in them? The silent treatment when I refuse to leave the house wearing two turtlenecks as requested? Or maybe loud, heaving sobs from both my parents when I mention my boyfriend’s name in the most innocent of circumstances (his ability to make risotto, his willingness to do my laundry, his affection for small animals and children). It could be anything. Telling the truth is the good, healthy thing to do, but for some people, the nicest thing you can do is feed them lie after lie after lie, until one of you is given the gift of sweet, blissful death.