Several years ago, the illustrator and cartoonist Jillian Tamaki told me:

“I revel in ambiguity … I think that being too literal is the death of a lot of good art. When I tell my students, it’s like: ‘You don’t need to be so literal, people have brains. They can fill in the blanks.’ That’s why people see Jesus in toast. You know what I’m saying? You just need a few landmarks to represent something, and I think conceptually it’s the same way. You don’t need to draw everything out—conceptually, I mean, draw everything out—so literally. The ambiguity and the spaces in between are actually what’s interesting.”

Tamaki’s new graphic novel This One Summer, written by her cousin Mariko, finds a perch in such liminal spaces—the slight but integral age gap between near-teen Rose and her younger friend Windy, and the turbulent landscapes they’re drawn into.

When This One Summer begins, Rose are her parents are en route to Awago Beach, somewhere in Ontario cottage country, which, if you’ve never been, is pretty almost to the point of tedium, a thousand similarly picturesque lakes, all the placid little towns with names like Elmvale and economies based on fudge production. Tamaki’s flamboyant compositions make this setting strange again without resorting to the forbidding clichés of Canadian art, the Group of Seven’s stoic and pristine pines. Her brushstrokes linger on fleeting elements of the elements: ethereal milkweed, the distorting glow of a campfire, waves as thin and pale as scars. They might be portents of the unsettled state that Mariko Tamaki’s script slowly reveals, more beguiling for how insubstantial they appear. The terse, bantering dialogue, where somebody’s words often strain to disavow their emotions, leaves mounting anxiety as another feature of the background.

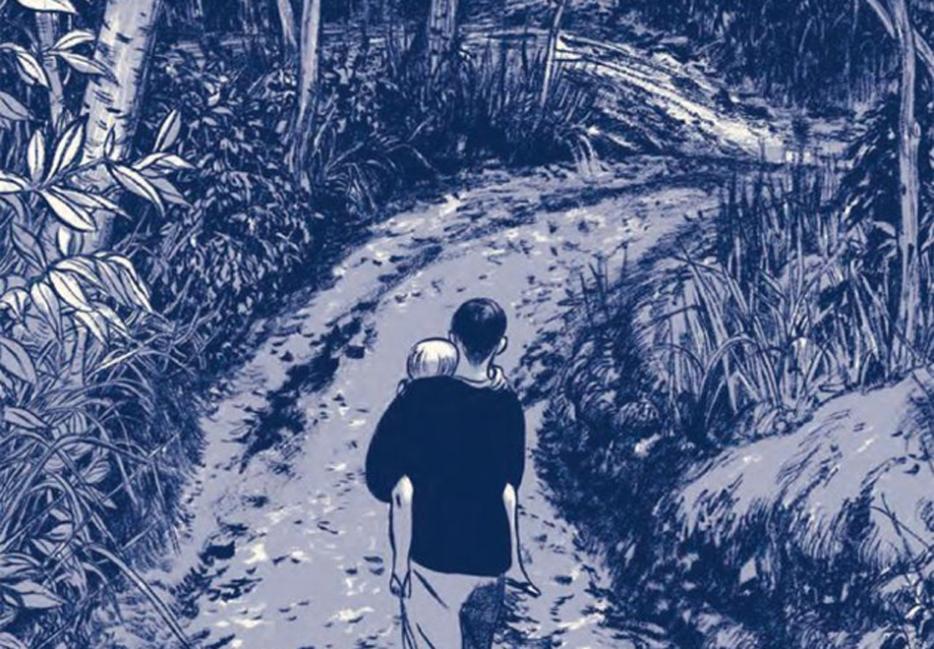

In their previous collaboration Skim, the cousins followed a teenage Wiccan’s doomed affair with her teacher Ms. Archer, and then followed her a while longer. (“I mean, there’s heartbroken and then there’s all the stuff that comes each second after that, depending on who broke your heart.”) The titular outcast—not gothy enough for a Fairuza Balk coven, not popular enough for the Girls Celebrate Life club—shuffled through a Toronto suburb that didn’t look like the endless strip mall of stereotype. Tamaki drew the Scarborough of chthonic ravines and mismatched ruins, as if civilization were nothing more than a flaking layer of paint. I thought of that again reading one early page in This One Summer, where Rose’s father carries her sleepy form to their cottage; branches snake around each other overhead, ink grows thickly on all sides, and at first glance it seems unclear whether they’re heading towards shelter or deeper into the forest.

Rose and Windy keep renting slasher movies from Awago Beach’s lone corner store, and here the perspective zooms in, never showing much more than a grainy laptop screen or disembodied screams. They’re still barely young enough to consider this a little scandalous. But Rose has begun to eye one of the store’s bored slacker employees, who may or may not be breaking up with his girlfriend, who may or may not be pregnant, which may or may not be his fault. She follows him around almost like a detective, something she can figure out, unlike what appears to be the erosion of her parents’ marriage. These two stories meet near the water, an environment both Tamakis never leave for long—perhaps because it turns so mercurial in the rendering, like Windy. (There is a marvelous double-page spread where she dances herself across the room while Rose quietly grooves along in her chair.) The dark-navy tint of the book makes everything look a little bit damp, or faded.

As florid as Jillian’s line is, neither she nor Mariko romanticize the lake much: it’s just a place where people swim, and occasionally feel terror. One of my favourite compositions takes a near-abstract image of pulsing raindrops and superimposes a detail from a reassuring email Rose’s father sent: “Hey Kiddo! Just a short n…” It’s as if you were looking at some subdued canvas and noticed an ominously friendly note stuck onto it. By the end of This One Summer, each character gains a certain clarity about their situation, but dilemmas remain unresolved, the future undecided. Rose watches Windy wave goodbye through her rear-view mirror, hand clenching the backseat. A hundred pages before that, when they get into a fight, Rose turns and dives back into the water, this tiny crease of curling lines amidst empty white space. The landscape is not the territory.