When I was in junior high, there was a trend of boys going up to girls they liked (using “liked” rather generously here) and pulling down their pants in public. This was in the time of Juicy Couture sweatpants, those loose-fitting, candy-coloured terry-cloth items that sat low on your hips and really let your muffin top breathe.

The boys targeted the popular girls, eager to see their underwear, the underside of their butt, their pubic bone. Truly, junior high boys are treasures.

Finally, they got Alex, a thin, beautiful, popular girl who wore a pink velour tracksuit, pants barely hanging off her hipbones. (Do not judge: it was the early aughts, and I, for one, was so jealous of her horrible, horrible style that I wanted to kill myself when she came to junior prom with a bitchin’ leopard-print dye-job.)

They pulled her pants down in front of the art room and gathered around in awe. They’d caught a big fish: Alex was wearing the tiniest thong conceivable. She froze, her exposed bottom half available to everyone’s eyes, in the middle of the hallway.

The school implemented a dress code later that month for girls exclusively. They told us that maybe, just maybe, this incident could have been avoided if Alex had just worn tighter pants.

The issue, it seemed, wasn’t that Alex’s expectation of privacy was infringed upon in a particularly humiliating and aggressive way, but rather that she didn’t anticipate it in the first place. She wore something that opened her up to attack. Her body, including the parts she thought she’d effectively hidden from the public eye, was everyone’s business.

Maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised that the Massachusetts Supreme Court is just as ill prepared to handle this sort of incident as a crumbling junior high in suburban Calgary. The court recently tossed out charges against Michael Robertson, who was caught taking up-skirt pictures of women on public transportation back in 2010. What was the logic behind the decision? The law used to prosecute him is, apparently, only valid if the women are “nude” or “partially nude.” That is, a photo taken under someone’s clothes does not count.

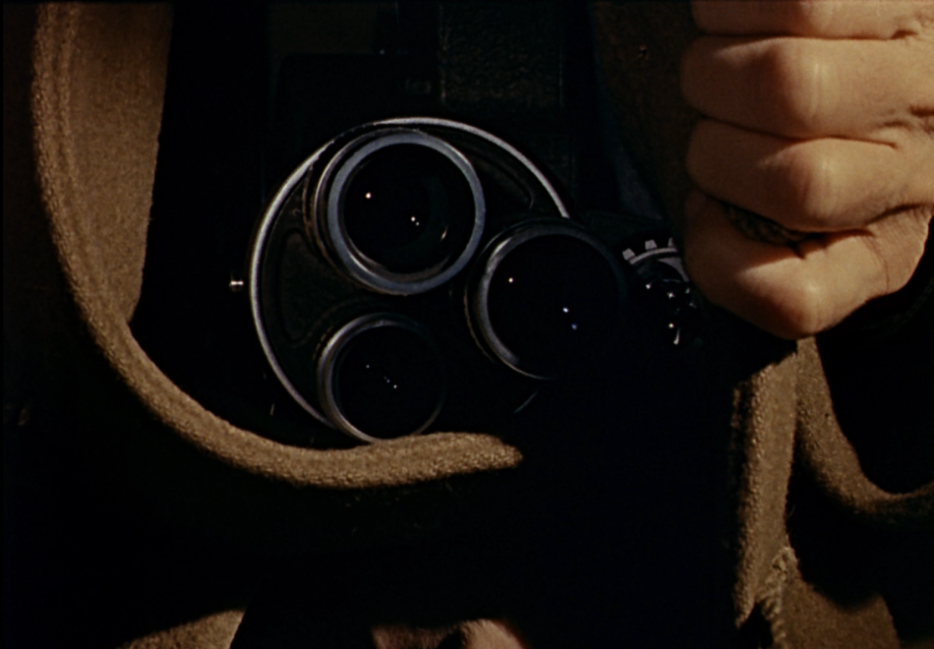

House Speaker Robert DeLeo said “the House will begin work on updating our statuses to conform with today’s technology immediately.” I had no idea that the camera—which has, historically, often appeared detached from a phone, and has been in existence for longer than DeLeo has been alive—was considered modern technology! We can only hope that the House soon acknowledges the invention of the personal computer—truly a great triumph of the 21st century—and allows government officials to begin to incorporate the ZX Spectrum into their daily processes.

Just because the technology is arriving in a slightly different form doesn’t mean the attendant problems are new, or have fundamentally changed. The issue of capturing images in public came up last week, when a San Francisco bar banned Google Glass after customers expressed concerns about being filmed by Silicon Valley dopes. Google Glass in particular has reignited many of the same anxieties people suffered from in that era before smartphones became ubiquitous, but there’s little practical difference. No one wants to feel like they’re being watched.

Being filmed drinking at a bar is, of course, a separate issue from someone filming underneath your dress. We are increasingly being conditioned to hold a smaller and smaller expectation of privacy—oh, you’re using private browsing, good for you, you pervert, we know you’re looking at butt stuff—but if there’s anywhere we should be allowed to dictate the terms, it should be our bodies.

Setting aside the obvious moral implications of up-skirt photos, the court’s decision isn’t just about privacy—it’s about why women’s bodies in particular are not private.

Everyone knows what up-skirts are—a depraved industry unto themselves, and an invasion unique to women. If men wore shorts billowy enough that women could kneel down and take a snapshot of their balls, it would be considered both an infringement on basic decency and an activity for the criminally insane.

Women’s bodies, however, remain commoditized in a way men’s are not. They’re items available for public consumption. They sell deodorant that makes our armpits beautiful; they think we need our own special butt powder. And sure, men are used commercially in this way, too, but not to the same extent. If men are hunting and seeking, women are waiting to be plucked.

Consequently, women are still taught to expect and anticipate that they will be treated like items men already own. Our bodies belong to the public, and if a woman isn’t smart enough to wear bike shorts under her skirt, or thoughtful enough to not stand next to a guy with a smartphone, she gets what she gets. Still among us are men who believe that if a woman is in their general proximity, they can do what they please to and around her merely because, hey, she’s there.

We’ve already had to make it explicit that you can’t pinch, poke, prod, or grope women on the subway. By this logic, we apparently also need to clearly and unequivocally state that you cannot put your phone inside a woman’s clothes in order to take a picture of a part of her body that she is very obviously not showing you. Somehow, the expectation is that if you can see her, and if you can get access to her, she’s fair game for your amateur urban erotica.

I expect privacy nowhere. I know I’m being watched wherever I go. I assume I’m being filmed when I leave my house for a coffee. I know IT tracks my keystrokes when I Google “cures for itchy nipples” at work. I always put a piece of tape over my webcam because I’m waiting for it to just turn on one day without my noticing. But at the very least, I would hope that if I must occasionally share public transit with monsters, that it would be illegal for them to capture images of parts of me that I was not already presenting for general consumption. That is the hope, but of course, it’s rarely the actuality.

Or who knows, maybe this is all a conspiracy perpetrated by the bloomer industry to push women to cover up underneath what they’re wearing to cover up. Massachusetts is, after all, a state rich with history.