There’s a segment in Arabian Nights, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s loose adaptation of the ancient Persian folk tales and his penultimate film, which encapsulates the director’s sensibility. The scene relates the well-known story of Aziz and his cousin Aziza, to whom he has been arranged to marry. On the morning of the ceremony, Aziz, briefly leaving the proceedings to fetch a missing guest, happens upon a young woman in town named Badur, whose beauty proves such a distraction that he fails to return in time to be wed. Aziza, though devastated, loves her fiancé so deeply that she conspires to help him win the affections of the woman of whom he’s now clearly enamored, guiding him through a series of arcane rituals and challenges in code toward the object of his desire. Aziz soon prevails and is united with Badur; Aziza, her sacrifice complete, suddenly dies. The story ends when Badur decides to murder Aziz as punishment for his cruelty to his former fiancé. In a desperate appeal for clemency he invokes an aphorism offered by Aziza before her death: “Fidelity is splendid, but not more than infidelity.” Badur relents, opting for a different sort of retribution: she castrates him.

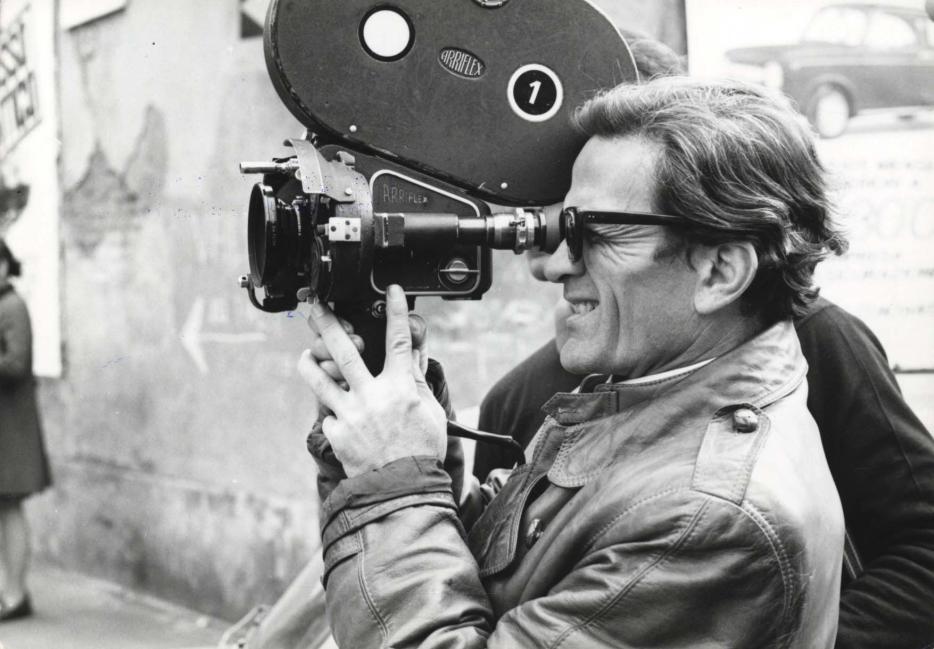

This sequence, which spans no more than 15 minutes and concludes with the end of the film’s first act, contains nearly every hallmark for which Pasolini’s rather diverse filmography remains best known. Pasolini, broadly speaking, is a difficult artist to pin down or summarize. Over the course of only 14 years the Italian writer, poet, journalist, painter, and public intellectual somehow found the time to direct a staggering 15 feature films—a complete retrospective of which begins Saturday, March 8th at the TIFF Bell Lightbox in Toronto—which together cover an exceptional variety of styles, modes and themes. Consider the diversity of interests suggested by the Arabian Nights story alone: like his early neo-realistic pictures, Accattone and Mamma Rosa, it finds Pasolini embracing the reality of the world as it lay before him, shooting on location in Yemen, Iran, Nepal, and Eritrea with a minimal crew and a cast composed of nonprofessional actors. Like his other literary adaptations, and in particular The Decameron and The Canterbury Tales, it furnishes a traditional story with flourishes of modernism, reciting iconic material with a novel and often surprising inflection. And like his most notorious film, Salo or the 120 Days of Sodom, it’s as shocking in its approach to pain as to pleasure.

And then he leaves. Feeling themselves abandoned, the family begins to fall apart: the daughter slips into sudden catatonia and is hauled off to an asylum; the son loses himself to abstract art until he’s found urinating on his canvases; the maid quits, returns to her working-class village, and sits in stoic silence without food and water until, in a burst of divine transcendence, she starts levitating in the air; and the industrialist father, in the film’s extraordinary last scene, sheds his clothes on the factory floor and wanders off into the desert, where he sounds a barbaric yawp. It’s an ending not unlike Mamma Roma: a tragic figure stares out into the void, ruined by loss. But where Mamma Rosa grounded its story of a reformed prostitute and her law-breaking son firmly in the streets of modern Italy, Teorema looks to the expanded canvas of fantasy and allegory, where Pasolini can articulate his themes on a cosmic scale. The effect is commensurately profound.

Let’s return, finally, to the story of Aziz and Aziza—what interested Pasolini in the story to begin with? We see him deploy in the sequence his favoured styles, themes, and methods; but the significance in fact runs deeper. For Pasolini, the story of Aziz and Aziza was chiefly autobiographical. Aziz was played in the film by Ninetto Davoli, the actor who had performed in 11 of Pasolini’s films and had shared with him a secret romance for more than 10 years. Critic Colin McCabe explains, in an essay on the film, that shortly before production began on Arabian Nights, Davoli had “broken Pasolini’s heart by deciding to marry, leaving the director.” It seems clear that Pasolini saw himself as the Aziza to Davoli’s Aziz—the spurned lover sacrificing his happiness and ultimately dying of heartbreak. In this light the sequence becomes doubly powerful: we are watching as a man depicts his own rejection at the hand of the actor in the scene, an allegory with painfully real consequences. This, too, seems a succinct encapsulation of the genius of Pasolini: amidst all the sex and violence lay the real candor, that of putting his own heart and mind on the line.

The Poet Of Contamination, a complete retrospective of the films of Pier Paolo Pasolini, begins Saturday March 8th at the TIFF Bell Lightbox in Toronto.