The comedian James Adomian specializes in impressions, and one of his best is Jesse Ventura, always pronounced like the defensive fortification. As a World Wrestling Federation star during the 1980s, the naval veteran and future-ex-Minnesota-governor and Harvard-fellow played “The Body,” an arrogant devotee of California beaches and physical fitness. Adomian’s Ventura acts as if that sneering assurance was an act he never dropped, e.g. while discussing the self-refuting name of his TruTV series Conspiracy Theory: “I wanted to call it Questionable Information with Jesse Ventura, but the network wouldn’t go for it. They wanted Old Wives’ Tales Whispered on a Sunday Picnic Blanket to Jesse ‘The Generous Lover’ Ventura. Or Barstool Hearsay Overheard by Jesse ‘The Day Drunk’ Ventura.”

I was never a wrestling fan myself. I first encountered Jesse Ventura via Predator, alongside an Arnold Schwarzenegger just emerging from his “impassive meat golem” phase into the manic unreality of Total Recall and Last Action Hero. Pro wrestlers would show up in the action movies I watched as a kid, but they seldom got the quips or the metatextual Hamlet jokes. They were relegated to mute muscle. I only belatedly appreciated what a waste this was, the idiosyncratic skills modern wrestling cultivates. It’s live theatre simultaneously broadcasting to millions of TV viewers, a melodrama of unstable feuds, camp without any aristocratic detachment. You don’t just have to take a folding-chair beating and get up again; you also have to look into a camera and snarl that your rivals will all be flamboyantly annihilated. In the struggle between heels (enraging, captivating villains) and faces (boring good guys), a persona might somersault across those boundaries mid-fight. The most insanely Jesse-Ventura-ish line he’s ever said came from the Governor, not the Body: “Until you’ve hunted man, you haven’t hunted yet.”

Not that anybody can necessarily move from ring to screen. Despite not following wrestling—mainly I hear about it from friends—I have still somehow seen 2006’s The Marine, essentially a 90-minute excuse for ultra-face John Cena to hit Robert Patrick with a truck. Although the renamed WWE was pursuing its own film productions by then, Dwayne Johnson (a.k.a. The Rock) became the first true ex-wrestler movie star more or less on his own. Repeatedly turning from heel to face and back again, he was charismatic enough to turn a mere raised eyebrow into a signature taunt. What’s irresistible about The Rock is how he wears his aerial bomb of a frame so lightly, delighted to lip-sync Taylor Swift or vamp next to a Lamborghini on Instagram. There’s a scene in Fast & Furious 6 where he genially, playfully crushes some guy’s hand. The Rock’s face is a series of poses flush with self-aware mischief. He always seems to be thinking, “Isn’t it hilarious and cool that I’m a giant man?”

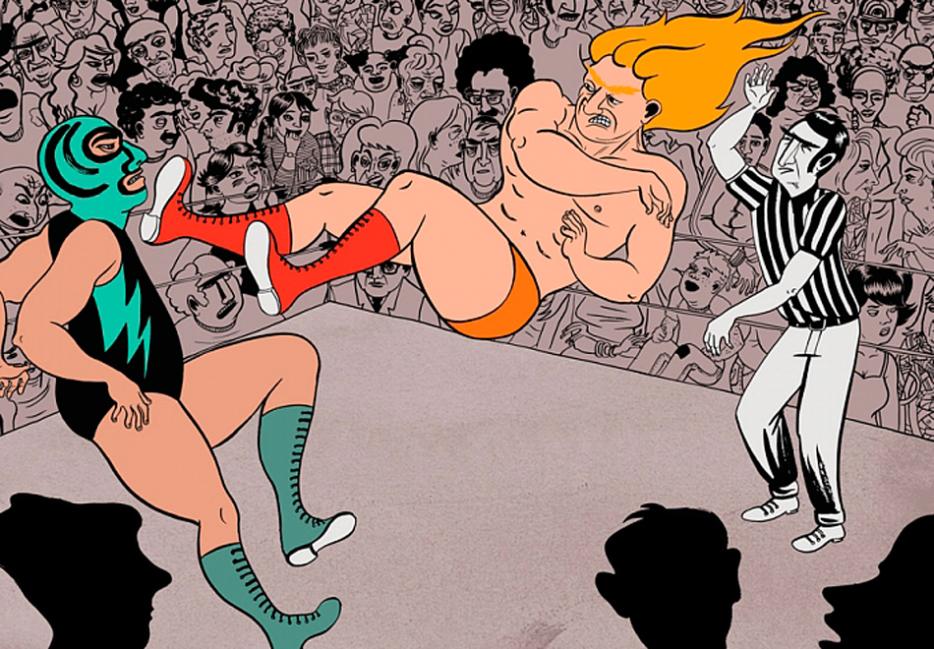

The new Mountain Goats album Beat the Champ mainly describes a wrestling era long before this, before even the cable-TV-driven boom of the 1980s. The band’s songwriter and core John Darnielle grew up in southern California, where his family would go to matches at the Grand Olympic Auditorium. Back then wrestling was still obscurely territorial. The local scene had a big Mexican-American presence, and “The Legend of Chavo Guerrero” hails Darnielle’s childhood hero, an avatar of righteousness his own violent stepfather would never be: “You called him names to try to get beneath my skin / Now your ashes are scattered on the wind.” The 1970s concluded a sustained decline of wrestling’s popularity, and Darnielle has always been sensitive to people living in ruin. Whether due to mental anguish, abusive environments, or a relationship resembling the weapons black market, his characters often carry festering trauma—fixated on some cryptic detail of a bricked-up room, and rituals to ward off the creature scraping at its walls.